Identification and Description of Feathers in Te Papa's Mäori Cloaks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Diurnal Raptors and Airports

Australian diurnal raptors and airports Photo: John Barkla, BirdLife Australia William Steele Australasian Raptor Association BirdLife Australia Australian Aviation Wildlife Hazard Group Forum Brisbane, 25 July 2013 So what is a raptor? Small to very large birds of prey. Diurnal, predatory or scavenging birds. Sharp, hooked bills and large powerful feet with talons. Order Falconiformes: 27 species on Australian list. Family Falconidae – falcons/ kestrels Family Accipitridae – eagles, hawks, kites, osprey Falcons and kestrels Brown Falcon Black Falcon Grey Falcon Nankeen Kestrel Australian Hobby Peregrine Falcon Falcons and Kestrels – conservation status Common Name EPBC Qld WA SA FFG Vic NSW Tas NT Nankeen Kestrel Brown Falcon Australian Hobby Grey Falcon NT RA Listed CR VUL VUL Black Falcon EN Peregrine Falcon RA Hawks and eagles ‐ Osprey Osprey Hawks and eagles – Endemic hawks Red Goshawk female Hawks and eagles – Sparrowhawks/ goshawks Brown Goshawk Photo: Rik Brown Hawks and eagles – Elanus kites Black‐shouldered Kite Letter‐winged Kite ~ 300 g Hover hunters Rodent specialists LWK can be crepuscular Hawks and eagles ‐ eagles Photo: Herald Sun. Hawks and eagles ‐ eagles Large ‐ • Wedge‐tailed Eagle (~ 4 kg) • Little Eagle (< 1 kg) • White‐bellied Sea‐Eagle (< 4 kg) • Gurney’s Eagle Scavengers of carrion, in addition to hunters Fortunately, mostly solitary although some multiple strikes on aircraft Hawks and eagles –large kites Black Kite Whistling Kite Brahminy Kite Frequently scavenge Large at ~ 600 to 800 g BK and WK flock and so high risk to aircraft Photo: Jill Holdsworth Identification Beruldsen, G (1995) Raptor Identification. Privately published by author, Kenmore Hills, Queensland, pp. 18‐19, 26‐27, 36‐37. -

New Zealand Comprehensive II Trip Report 31St October to 16Th November 2016 (17 Days)

New Zealand Comprehensive II Trip Report 31st October to 16th November 2016 (17 days) The Critically Endangered South Island Takahe by Erik Forsyth Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Erik Forsyth RBL New Zealand – Comprehensive II Trip Report 2016 2 Tour Summary New Zealand is a must for the serious seabird enthusiast. Not only will you see a variety of albatross, petrels and shearwaters, there are multiple- chances of getting out on the high seas and finding something unusual. Seabirds dominate this tour and views of most birds are alongside the boat. There are also several land birds which are unique to these islands: kiwis - terrestrial nocturnal inhabitants, the huge swamp hen-like Takahe - prehistoric in its looks and movements, and wattlebirds, the saddlebacks and Kokako - poor flyers with short wings Salvin’s Albatross by Erik Forsyth which bound along the branches and on the ground. On this tour we had so many highlights, including close encounters with North Island, South Island and Little Spotted Kiwi, Wandering, Northern and Southern Royal, Black-browed, Shy, Salvin’s and Chatham Albatrosses, Mottled and Black Petrels, Buller’s and Hutton’s Shearwater and South Island Takahe, North Island Kokako, the tiny Rifleman and the very cute New Zealand (South Island wren) Rockwren. With a few members of the group already at the hotel (the afternoon before the tour started), we jumped into our van and drove to the nearby Puketutu Island. Here we had a good introduction to New Zealand birding. Arriving at a bay, the canals were teeming with Black Swans, Australasian Shovelers, Mallard and several White-faced Herons. -

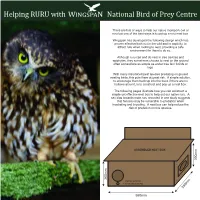

(Ruru) Nest Box

Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre There are lots of ways to help our native morepork owl or ruru but one of the best ways is to put up a ruru nest box. Wingspan has developed the following design which has proven effective both out in the wild and in captivity, to attract ruru when looking to nest, providing a safe environment for them to do so. Although ruru can and do nest in tree cavities and epiphytes, they sometimes choose to nest on the ground often somewhere as simple as under tree fern fronds or logs. With many introduced pest species predating on ground nesting birds, this puts them at great risk. A simple solution, to encourage them back up into the trees if there are no hollows around, is to construct and pop up a nest box. The following pages illustrate how you can construct a simple yet effective nest box to help out our native ruru. A sex bias towards male ruru recorded in one study suggests that females may be vulnerable to predation when incubating and brooding. A nest box can help reduce the risk of predation on this species. ASSEMBLED NEST BOX 300mm 260mm ENTRY PERCH < ATTACHED HERE 260mm 580mm Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre MATERIALS: + 12mm tanalised plywood + Galvanised screws 30mm (x39) Galvanised screws 20mm (x2 for access panel) DIMENSIONS: Top: 300 x 650mm Front: 245 x 580mm Back: 350 x 580mm Base: 260 x 580mm Ends: 260 x 260 x 300mm Door: 150 x 150mm Entrance & Access Holes: 100mm + + + TOP + 300x650mm + + + + + + + + BACK 350x580mm + + + + ACCESS + + FRONT + HOLE + 100x100 ENTRANCE 245x580mm HOLE END 100x100 END 260x260x300mm 260x260x300mm + + + + + + + + + + + ACCESS COVER 150x150mm + BASE + 260x580mm + + + + + Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre INSTRUCTIONS FOR RURU NEST BOX ASSEMBLY: Screw front and back onto inside edge of base (4 screws along each edge using pre-drilled holes). -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

The Nest, Eggs, and Diet of the Papuan Harrier from Eastern New Guinea

J. Raptor Res. 44(1):12–18 E 2010 The Raptor Research Foundation, Inc. THE NEST, EGGS, AND DIET OF THE PAPUAN HARRIER FROM EASTERN NEW GUINEA ROBERT E. SIMMONS1 DST/NRF Centre of Excellence, FitzPatrick Institute, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa ABSTRACT.—The Papuan Harrier (Circus spilonotus spilothorax), currently classified as a subspecies of the Eastern Marsh-Harrier (C. spilonotus), is endemic to the island of New Guinea and may be in need of conservation attention because of threats from grassland burning. I here detail the discovery of the first known nests in lowland Papua New Guinea and provide egg dimensions and prey data. Both nests were initiated in early April, in damp rank grassland, and contained three small chicks in mid-May. The only egg measurements, combined with one previously published record, suggest large egg volume and concomitant large female body size (estimated to be ca. 890 g). At this size, this may be the world’s largest harrier. Fire destroyed both nests within 5 wk of their discovery. An atypically slow foraging style and a preponderance of game birds and large rats (Rattus spp.) in the pellets and prey remains are consistent with large body size. Further studies of the bird’s ecology and breeding are needed for a comprehensive understanding of its conservation status and threats to its population. KEY WORDS: Papuan Harrier; Circus spilonotus spilothorax; Eastern Marsh-Harrier; Circus spilonotus; body size; diet; egg size; foraging; Papua New Guinea. NIDO, HUEVOS Y DIETA DE CIRCUS SPILONOTUS SPILOTHORAX DEL ESTE DE NUEVA GUINEA RESUMEN.—Circus spilonotus spilothorax, actualmente clasificada como una subespecie de C. -

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Ghana

Avibase Page 1of 24 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Ghana 2 Number of species: 773 3 Number of endemics: 0 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of globally threatened species: 26 6 Number of extinct species: 0 7 Number of introduced species: 1 8 Date last reviewed: 2019-11-10 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Ghana. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=gh [26/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Harrier References

Introduction This is the final version of the Harrier's list, no further updates will be made. Grateful thanks to Wietze Janse and Tom Shevlin (www.irishbirds.ie) for the cover images and all those who responded with constructive feedback. All images © the photographers. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and are best employed in conjunction with other sources. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds.) 2019. IOC World Bird List. Available from: https://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 9.1 accessed January 2019]). Final Version Version 1.4 (January 2019). Cover Main image: Western Marsh Harrier. Zevenhoven, Groene Jonker, Netherlands. 3rd May 2011. Picture by Wietze Janse. Vignette: Montagu’s Harrier. Great Saltee Island, Co. Wexford, Ireland. 10th May 2008. Picture by Tom Shevlin. Species Page No. African Marsh Harrier [Circus ranivorus] 8 Black Harrier [Circus maurus] 10 Cinereous Harrier [Circus cinereus] 17 Eastern Marsh Harrier [Circus spilonotus] 6 Hen Harrier [Circus cyaneus] 11 Long-winged Harrier [Circus buffoni] 9 Malagasy Harrier [Circus macrosceles] 9 Montagu's Harrier [Circus pygargus] 20 Northern Harrier [Circus hudsonius] 16 Pallid Harrier [Circus macrourus] 18 Papuan Harrier [Circus spilothorax] 7 Pied Harrier [Circus melanoleucos] 20 Réunion Harrier [Circus maillardi] 9 Spotted Harrier [Circus assimilis] 9 Swamp Harrier [Circus approximans] 7 Western Marsh Harrier [Circus aeruginosus] 4 1 Relevant Publications Balmer, D. et al. 2013. Bird Atlas 2001-11: The breeding and wintering birds of Britain and Ireland. BTO Books, Thetford. Beaman, M. -

Volume 29 Number 1 April 2011

BOOBOOK JOURNAL OF THE AUSTRALASIAN RAPTOR ASSOCIATION Volume 29 Number 1 April 2011 ARA CONTACTS President: Victor Hurley 0427 238 898 [email protected] Secretary Nick Mooney 0427 826 922 [email protected] Treasurer VACANT Webmaster VACANT Editor, Boobook Dr Stephen Debus 02 6772 1710 (ah) [email protected] Boobook production Hugo Phillipps Area Representatives: ACT Mr Jerry Olsen [email protected] NSW Dr Rod Kavanagh [email protected] NT Mr Ray Chatto [email protected] Qld Mr Stacey McLean [email protected] SA Mr Ian Falkenberg [email protected] WA Mr Jonny Schoenjahn [email protected] Tas Mr Nick Mooney [email protected] Vic Mr David Whelan [email protected] New Zealand VACANT PNG/Indonesia Dr David Bishop [email protected] Other BOPWatch liaison Victor Hurley [email protected] Editor, Circus Victor Hurley Captive raptor advisor Michelle Manhal 0418 387 424 [email protected] Education advisor Greg Czechura 07 3840 7642 (bh) [email protected] Raptor management Nick Mooney 0427 826 922 [email protected] advisor Membership enquiries Membership Officer, Birds Australia, Suite 2-05, 60 Leicester Street, Carlton, Vic. 3053 Ph. 1300 730 075, [email protected] Annual subscription $A30 single membership, $A35 family and $A45 for institutions, due on 1 January. Bankcard and MasterCard can be debited by prior arrangement. Website: www.birdsaustralia.com.au/ara The aims of the Association are the study, conservation and management of diurnal and nocturnal raptors of the Australasian Faunal Region. -

Southwest Pacific Islands: Samoa, Fiji, Vanuatu & New Caledonia Trip Report 11Th to 31St July 2015

Southwest Pacific Islands: Samoa, Fiji, Vanuatu & New Caledonia Trip Report 11th to 31st July 2015 Orange Fruit Dove by K. David Bishop Trip Report - RBT Southwest Pacific Islands 2015 2 Tour Leaders: K. David Bishop and David Hoddinott Trip Report compiled by Tour Leader: K. David Bishop Tour Summary Rockjumper’s inaugural tour of the islands of the Southwest Pacific kicked off in style with dinner at the Stamford Airport Hotel in Sydney, Australia. The following morning we were soon winging our way north and eastwards to the ancient Gondwanaland of New Caledonia. Upon arrival we then drove south along a road more reminiscent of Europe, passing through lush farmlands seemingly devoid of indigenous birds. Happily this was soon rectified; after settling into our Noumea hotel and a delicious luncheon, we set off to explore a small nature reserve established around an important patch of scrub and mangroves. Here we quickly cottoned on to our first endemic, the rather underwhelming Grey-eared Honeyeater, together with Nankeen Night Herons, a migrant Sacred Kingfisher, White-bellied Woodswallow, Fantailed Gerygone and the resident form of Rufous Whistler. As we were to discover throughout this tour, in areas of less than pristine habitat we encountered several Grey-eared Honeyeater by David Hoddinott introduced species including Common Waxbill. And so began a series of early starts which were to typify this tour, though today everyone was up with added alacrity as we were heading to the globally important Rivierre Bleu Reserve and the haunt of the incomparable Kagu. We drove 1.3 hours to the reserve, passing through a stark landscape before arriving at the appointed time to meet my friend Jean-Marc, the reserve’s ornithologist and senior ranger. -

Hunter Economic Zone

Issue No. 3/14 June 2014 The Club aims to: • encourage and further the study and conservation of Australian birds and their habitat • encourage bird observing as a leisure-time activity A Black-necked Stork pair at Hexham Swamp performing a spectacular “Up-down” display before chasing away the interloper - in this case a young female - Rod Warnock CONTENTS President’s Column 2 Conservation Issues New Members 2 Hunter Economic Zone 9 Club Activity Reports Macquarie Island now pest-free 10 Glenrock and Redhead 2 Powling Street Wetlands, Port Fairy 11 Borah TSR near Barraba 3 Bird Articles Tocal Field Days 4 Plankton makes scents for seabirds 12 Tocal Agricultural College 4 Superb Fairy-wrens sing to their chicks Rufous Scrub-bird Monitoring 5 before birth 13 Future Activity - BirdLife Seminar 5 BirdLife Australia News 13 Birding Features Birding Feature Hunter Striated Pardalote Subspecies ID 6 Trans-Tasman Birding Links since 2000 14 Trials of Photography - Oystercatchers 7 Club Night & Hunterbirding Observations 15 Featured Birdwatching Site - Allyn River 8 Club Activities June to August 18 Please send Newsletter articles direct to the Editor, HBOC postal address: Liz Crawford at: [email protected] PO Box 24 New Lambton NSW 2305 Deadline for the next edition - 31 July 2014 Website: www.hboc.org.au President’s Column I’ve just been on the phone to a lady that lives in Sydney was here for a few days visiting the area, talking to club and is part of a birdwatching group of friends that are members and attending our May club meeting. -

Bontebok Birds

Birds recorded in the Bontebok National Park 8 Little Grebe 446 European Roller 55 White-breasted Cormorant 451 African Hoopoe 58 Reed Cormorant 465 Acacia Pied Barbet 60 African Darter 469 Red-fronted Tinkerbird * 62 Grey Heron 474 Greater Honeyguide 63 Black-headed Heron 476 Lesser Honeyguide 65 Purple Heron 480 Ground Woodpecker 66 Great Egret 486 Cardinal Woodpecker 68 Yellow-billed Egret 488 Olive Woodpecker 71 Cattle Egret 494 Rufous-naped Lark * 81 Hamerkop 495 Cape Clapper Lark 83 White Stork n/a Agulhas Longbilled Lark 84 Black Stork 502 Karoo Lark 91 African Sacred Ibis 504 Red Lark * 94 Hadeda Ibis 506 Spike-heeled Lark 95 African Spoonbill 507 Red-capped Lark 102 Egyptian Goose 512 Thick-billed Lark 103 South African Shelduck 518 Barn Swallow 104 Yellow-billed Duck 520 White-throated Swallow 105 African Black Duck 523 Pearl-breasted Swallow 106 Cape Teal 526 Greater Striped Swallow 108 Red-billed Teal 529 Rock Martin 112 Cape Shoveler 530 Common House-Martin 113 Southern Pochard 533 Brown-throated Martin 116 Spur-winged Goose 534 Banded Martin 118 Secretarybird 536 Black Sawwing 122 Cape Vulture 541 Fork-tailed Drongo 126 Black (Yellow-billed) Kite 547 Cape Crow 127 Black-shouldered Kite 548 Pied Crow 131 Verreauxs' Eagle 550 White-necked Raven 136 Booted Eagle 551 Grey Tit 140 Martial Eagle 557 Cape Penduline-Tit 148 African Fish-Eagle 566 Cape Bulbul 149 Steppe Buzzard 572 Sombre Greenbul 152 Jackal Buzzard 577 Olive Thrush 155 Rufous-chested Sparrowhawk 582 Sentinel Rock-Thrush 158 Black Sparrowhawk 587 Capped Wheatear -

Some Makueni Birds

Page 164 Vol. XXIII. No.4 (101) SOME MAKUENI BIRDS By BASIL PARSONS A few notes on the birds of Makueni, a very rich area less than 90 miles from Nairobi, may be of interest. Most of this country is orchard bush in which species of Acacia, Commiphora, and Combretum predominate, with here and there dense thickets, especially on hillsides. Despite Kamba settlement there is ~till a wealth of bird life. The average height above sea level is about 3,500 feet, and the 'boma' where we live is at 4,000 feet. To the west and south-west are fine hills with some rocky precipices, the most notable being Nzani. Much of my bird-watching has been done from a small hide in the garden situated about six feet from the bird-bath, which is near a piece of uncleared bush, and in this way I have been able to see over 60 species at really close range, many of them of great beauty. Birds of prey are very numerous. The Martial Eagle rests nearby and is some• times seen passing over. The small Gabar Goshawk raids our Weaver colony when the young are fledging, I have seen both normal and melanistic forms. The Black• shouldered Kite is often seen hovering over the hill slopes, and the cry of the Lizard Buzzard is another familar sQund. Occasionally I have seen the delightful Pigmy Falcon near the house. Grant's Crested and Scaly Francolins both rouse us in the early morning. On one occasion a pair of the former walked within three feet of my hide.