Richard Hanson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Liner Notes

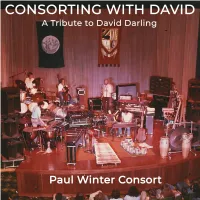

Cover Photo: Paul Winter Consort, 1975 Somewhere in America (Clockwise from left: Ben Carriel, Tigger Benford, David Darling, Paul Winter, Robert Chappell) CONSORTING WITH DAVID A Tribute to David Darling Notes on the Music A Message from Paul: You might consider first listening to this musical journey before you even read the titles of the pieces, or any of these notes. I think it could be interesting to experience how the music alone might con- vey the essence of David’s artistry. It would be ideal if you could find a quiet hour, and avail yourself of your fa- vorite deep-listening mode. For me, it’s flat on the floor, in total darkness. In any case, your listening itself will be a tribute to David. For living music, With gratitude, Paul 2 1. Icarus Ralph Towner (Distant Hills Music, ASCAP) Paul Winter / alto sax Paul McCandless / oboe David Darling / cello Ralph Towner / 12-string guitar Glen Moore / bass Collin Walcott / percussion From the album Road Produced by Phil Ramone Recorded live on summer tour, 1970 This was our first recording of “Icarus” 2. Ode to a Fillmore Dressing Room David Darling (Tasker Music, ASCAP) Paul Winter / soprano sax Paul McCandless / English horn, contrabass sarrusophone David Darling / cello Herb Bushler / Fender bass Collin Walcott / sitar From the album Icarus Produced by George Martin Recorded at Seaweed Studio, Marblehead, Massachusetts, August, 1971 3 In the spring of 1971, the Consort was booked to play at the Fillmore East in New York, opening for Procol Harum. (50 years ago this April.) The dressing rooms in this old theatre were upstairs, and we were warming up our instruments there before the afternoon sound check. -

The Cathedral Gives Back

Winter 2017–18 1047 Amsterdam Avenue Volume 16 Number 75 at 112th Street New York, NY 10025 (212) 316-7540 stjohndivine.org 2017 Winter –18 at the Cathedral The Cathedral Gives Back or where your treasure is, there your the Cathedral. I want to be able to do more than just talk In addition to our own programs, the Cathedral has also long heart will be also.” The Right Reverend about the things we believe in here, but also show our beliefs partnered with other mission-aligned community organizations Dan Daniel quoted Jesus’s Sermon on in action. We do this through our programs—Cathedral to support their work, something Dean Daniel wants to continue the Mount when asked about the Community Cares, Adults and Children in Trust, and the myriad to emphasize in our public programs. Longtime readers of this Cathedral’s commitment to tithing. of events that help underserved populations, but also through newsletter will recall the Cathedral’s collaboration with Broadway Typically seen as a way for people of donating to causes that we believe in.” Cares/Equity Fights AIDS to produce staged readings of Joan faith to give back to the church, Dean Didion’s haunting A Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights, The Cathedral has a long tradition of social outreach and Daniel takes the tradition a step further, the proceeds from which benefited UNICEF and The United commitment to community. Cathedral Community Cares (CCC) viewing it as a sacred obligation for the Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the works to combat and alleviate poverty through preventive F Cathedral to give back to the community. -

Concert Booklet April 22, 2017

North Shore Choral Society ©Virginia O. Roeder Missa Gaia-Earth Mass April 22, 2017 Unitarian Church of Evanston Evanston, Illinois Julia Davids, Music Director with Evanston Children’s Choir Thomas R. Jefferson, piano Felicia Patton, soprano Guabina Chiquinquirena ....................... Daniel Bayona Posada, arr. D.Wallenberg A Red, Red Rose ........ Robert Burns, text; James Mulholland, music; arr. G.Geiger Some Nights ........................ J.Bhasker, A.Dost, J.Antonoff, N.Ruess, arr.Mac Huff Amani (Peace) ..................................................................................... Jim Papoulis Evanston Children’s Choir Gary Geiger, director Hyejin Joo, accompanist ~ Intermission ~ Missa Gaia – Earth Mass Paul Winter, Jim Scott, Paul Halley, Oscar Castro-Neves, Kim Oler Canticle of Brother Sun (Audience joins chorus; music in Text and Translation) Kyrie The Beatitudes Sound Over All Waters .......................................................................... Paul Halley Sanctus and Benedictus His Eye Is on the Sparrow ........................................................ Traditional Spiritual Agnus Dei Ubi Caritas ............................................................................................. Paul Halley The Blue Green Hills of Earth (Audience joins chorus; music in Text and Translation) Let Us Depart in Peace (Audience joins chorus; music in Text and Translation) TEXT AND TRANSLATION CANTICLE OF BROTHER SUN “Having decided to dedicate the Earth Mass to St. Francis … I wanted to create a piece based on his ‘Canticle of Brother Sun.’” Paul Winter All praise be yours through Brother Sun. All praise be yours through Sister Moon. By Mother Earth my Lord be praised, by Brother Mountain, Sister Sea. Through Brother Wind and Brother Air, through Sister Water, Brother Fire; The stars above give thanks to thee; all praise to those who live in peace. All praise be yours through Brother Wolf, all praise be yours through Sister Whale. -

WMRA Holiday Broadcast Schedule 2004

WMRA Holiday Broadcast Schedule 2004 Winter Solstice Celebration, this year with a decidedly Russian flavor: The Dmitri Pokrovsky Ensemble-Russian village dancers Tuesday, Dec. 7th and singers-- joins African mbira master Chris Berry and the famous Paul Winter Consort. They'll lead our "Journey Through 7pm A Taste of Chanukah the Longest Night" with new works and old favorites including "Dancing Day," the West African "Minuit" and Paul Winter's This celebration of Chanukah features over 150 musicians from "Icarus." Wolves, whales and the audience in New York's the New England Conservatory, the Boston Community Choir Cathedral of St. John the Divine join in with holiday glee. 2 and other ensembles. The show is recorded live at the New hours. England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall in Boston. 1 hour. 10pm The Christmas Revels: A Celebration of the Winter Solstice Wednesday, Dec. 8th The Christmas Revels: A Celebration of the Winter Solstice 2004 7pm Chanukah in Story and Song is an all-new compilation of carols, rounds, drinking songs, music-hall numbers, madrigals and motets, children's singing A Chanukah celebration featuring The Western Wind and games, wassails, and traditional, social, and ritual dance tunes, narrated by Leonard Nimoy. They will present many eclectic selected from the nine live Christmas Revels performances that selections, from the Ladino songs of the Spanish Jews and took place around the country last year. 2 hours. Yiddish melodies of Eastern Europe to modern Israeli tunes. 1 hour. st Tuesday, Dec. 21 Thursday, Dec. 9th 7pm Christmas at El Pardo 7pm Chanukah Lights Christmas at El Pardo presents a magnificent hour-long concert of Father Antonio Soler's Christmas villancicos (songs) with brief A collection of readings that explore Chanukah traditions in interludes of plain chant. -

Page 1 N E W R E L E a S E

NEW RELEASE O N I N T U I T I O N R E C O R D S R E C E I V E D 4 G R A M M Y N O M I N A T I O N S OREGON’s latest project, Oregon In Moscow, is a double CD with the Moscow Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra, and the group’s recorded debut of their orchestral repertoire—a prodigious body of work that has been developing over the life of the band, but never documented. In the thirty-year history of OREGON, there has always existed a strong kinship to orchestral music. The use of the double reeds alone has given the quartet an identity and expansive sound associated with the symphonic orchestra. This association isn’t confined only to their use of many orchestral instruments, but applies also to the composition and presentation of the music, including the careful attention to details such as articulation, dynamics, phrasing and tone production derived from their respective classical studies. Chief composer Ralph Towner explains, “OREGON came together as a group in New York City in 1970, and from the outset it was clear that our unusual instrumentation and collective musical experience invited a different approach to composition and improvisation. The jazz tradition of improvisation usually consists of the soloists taking turns improvising on the song’s harmonic structure, recycling the chord progressions and returning to the original melody only on the last repeat of the cycle. While still using and honoring this tradition, we began composing longer, more sectional forms that allowed each soloist to improvise on different material within the context of a single piece. -

Eugene Friesen Interview

KITTY CAPARELLA LAURA SCHWARTZ ellist Eugene Friesen—artist, musician, educa- tor, collaborator, improviser—has been a musi- C cal idol of mine since I "rst heard him perform, Field Music, 2019 in 1989, at the Davies Symphony Hall in my hometown Yellow, gray, and cream encaustic paint-stick on wood, 12 x 12 in. A COVID-19 of San Francisco, California. That evening, I watched the Paul Winter Consort, Friesen’s artistic home for over four Conversation decades, perform with the Russian folk ensemble the Dmitri Pokrovsky Ensemble: American contemporary meets Rus- in B Minor sian traditional folk, in what could only be described as a supernatural metamorphosis of sound. An interview with I can still vividly recall seeing the consort members, Eu- gene Friesen on stage right in front of me, as they watched Eugene Friesen their Russian collaborators, colorful in their traditional peasant regalia, #ow down the aisles from the back of the music hall and onto the stage to join them—swirling, throat singing, smashing tambourines, clanging "nger cymbals, mixing all forms of percussion wildly and raucously with the consort’s smooth, contemporary jazz tones of saxophone, piano, cello, and drums. The consort members themselves appeared as trans"xed as I was: in this transcendent mo- ment, shared between performers and audience, the music itself was the star. COVID-19 led me to Friesen’s virtual door. I wanted to know what his work brought to him at this moment in time where every profession—and most profoundly, the perform- ing arts—had been leveled and brought to its knees. -

Connections T H E N E W S L E T T E R O F M U S I C F O R P E O P L E: Fall 2016

CoNNeCTioNS T h e N e w s l e t t e r o f M u s i c f o r P e o p l e: Fall 2016 30th Anniversary, October, 2016 CELEBRATING 30 YEARS OF MUSIC MAKING!! IN THIS ISSUE: • Page 2: David Darling - Gratitude • Page 2 : 30 for 30 Fundraising Campaign • Page 3-7: Jan Hittle - MFP Celebrates 30 Years: Interviews with Participants at the 30th Anniversary Celebration • Page 8-10 : David Rudge - Mindfulness Through Music • Page 11: Mary Knysh- Letter from the MLP Chair: The Art of Imrpovisation 2016 • Page 12-14: Jan Hittle - We Turned 30! Highlights from the 30th Anniversary Workshop Weekend • Page 15-16: Jim Oshinsky - Kudos to David Darling • Page 16: Carol Purdy - Book Review: Steal Like and Artist by Austin Kleon • Page 17: Congratulations to our MLP Graduates- Alison Weiner and Alina Plourde • Page 18-19: MUSICAL Advertisements • Page 20: Jane Buttars - Improvised Music Harvest Workshop, 2016 • Page 21: Lynn Saltiel - News from Lynn Saltiel and the MFP Improv Orchestra • Page 22: Mary Knysh - Book Reveiw: The Fear of Singing Breakthrough Program: Learn to Sing Even if You Can’t Carry a Tune, by Nancy Salwen • Page 23: Calendar of Events and Who We Are; Advertise! Page 1 Gratitude From David Darling Dear MFP Community, I wanted to send all of you my love and gratitude. Your support is a blessing. I felt so overjoyed and grateful to celebrate our community at our 30th Anniversary Celebration this past October. Thank You to the staff and the breakout and elective leaders for their tremendous skills in organizing and presenting at our anniversary event. -

BOCA RATON NEWS Vol

BOCA RATON NEWS Vol. 15, No. 35. Sunday, Jan. 25, 1970 32 Pages 10 Cents Reed eyes court pressure 9 One -manv vote district 'almost inevitable •«*• By PETE DONAGHUE has three state' senators, and runs all of his district — covering four counties chance to elect one of their own. the Miami Herald could control the one-member districts in 1971 becaua the way from the/Edst coast to Fort and with more than 50 cities and towns. "Coral Gables or Homestead could entire 22 member Dade County 1970 census information will be State Rep. Don Reed sees one- Myers. Two of. them, Skip Bafalis and "I have to spend seven days a week elect a Republican," he said. "Cubans delegation. If each legislator were computerized by tracts, rather than member Florida legislative districts in Jerry Thomas, live on this coast, while trying to represent all the people of and Negroes do not have proportionate elected from a smaller district, and be geographically definable boundaries; the near future. Sen. Elmer Friday comes from Fort this big district," he said. "Some representation in the Dade delegation able to be closer to his constituents. the information will be on tapes, and The Boca Raton House minority Myers. months I log nearly 4,000 miles within because it is elected at large. A Reed said, this influence would not be the state can buy the tapes. leader says the Supreme Court is All, however, must campaign the district plus 1,000 to 2,000 more legislator should represent the neigh- possible. Reed sees no reason legislative pushing the legislature with its one- throughout the run at-large in the going to Tallahassee for committee borhood in which he lives,Minority After the 1970 census, the new state man, one-vote mandate to the point entire district, which covers Glades, meetings and other speaking groups should have representatives constitution will require the legislature districts can't cross county lines, where one-member districts are Henry, Lee and Palm Beach Counties. -

In Sickness and Health: Cathedral Community Cares

Winter 2014–15 1047 Amsterdam Avenue Volume 13 Number 67 at 112th Street New York, NY 10025 (212) 316-7540 stjohndivine.org 2014 Winter –15 at the Cathedral In Sickness and Health: Cathedral Community Cares ew Yorkers have recently been faced Summer Health Fair in partnership with Mount Sinai-St. Luke’s “We cannot live only for ourselves. with the prospect of the Ebola virus Hospital and the NYC Sigma Gamma Rho sorority alumni group. loose in the city—a situation that the The Sunday Soup Kitchen serves roughly 25,000 meals a year, A thousand fibers connect us with Dean addresses in his Meditation this offering a diverse and healthy menu. This summer, CCC hosted our fellow men.” issue—and the headlines remind many a cooking class for low-income people, sponsored by Cornell of us, and the Cathedral as an University Cooperative Extension. Clients learned how to shop Herman Melville (1819–1891), institution, of what it was like during for and prepare inexpensive nutritional meals, and were taught inducted into the American Poets Corner in 1985 the last frightening (and continuing) epidemic: HIV/AIDS. There safe food-handling practices. As the Cathedral gears up for its This fall, CCC Program Manager Lauren Phillips attended a Nare many differences between the two viruses. What is the next initiative, The Value of Food, which will address everything weeklong professional workshop in Bolinas, California, same is the human suffering that affects individuals, families from sustainable agriculture to the use of food in cultural and sponsored by Commonweal Advanced Cancer Support Training. -

Fort Collins Local History Archive Finding Aid Title of Collection: Lincoln Center Collection Box ID: LC-1 Through 9

Fort Collins Local History Archive Finding Aid Title of Collection: Lincoln Center Collection Box ID: LC-1 through 9 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Creator: Lincoln Center Title: Lincoln Center Collection Date Range: 1976-2009 Brief description of collection: This collection was donated to the Local History Archive in 2010 by the Lincoln Center as they prepared for renovations to their facility. Quantity: 9.5 linear feet (8 record cartons, 1 16'' x 20'' scrapbook box) HISTORICAL INFORMATION The Lincoln Community Center opened on October 14, 1978 at 417 West Magnolia as Fort Collins’ arts and culture center. The name was later shortened to The Lincoln Center. It stands where the old Lincoln Junior High School once stood. The center features two performing art spaces (a 1,180-seat performance hall and a 220-seat theatre), three galleries, two conference/special events rooms, and an outdoor sculpture/terrace/performance garden. The Lincoln Center hosts a variety of events including traveling theater, music, and dance companies; local theater, music, and dance companies; school performances; community club events and performances; art exhibits; film series; and various other events. The Lincoln Center offers events and performances for all ages, including a children’s series. The Lincoln Center’s event rooms are rented for events by members of the community. The Lincoln Center is the primary source for viewing arts and culture for the Fort Collins community. It is part of the City of Fort Collins Culture, Parks, Recreation, & Environment Department. The Lincoln Center operated each season since its opening in 1978 through 2009. In 2010, the Lincoln Center closed for one year for renovation and expansion. -

High Costs Hit Webster House Residents

Students pay $ 50,000 High costs hit Webster House residents Last year roughly half as many operating on a $130 thousand “I don’t sense I can ask for heating in the house surfaced by George Forcier students lived at Webster House. deficit, Bianco said. funds that aren’t really there”. last week. According to Evans, Staff Reporter They paid $255 per semester. Webster House residents are “The subsidy issue may be these conditions resulted from The residents of Webster The Residence Office paid the consequently shouldering the en valid”, he added, but indicated the increases demand on the House, the former Theta Chi fra balance of the building’s yearly tire operating and rental cost of it would have to be discussed building’s plumbing and heating ternity house, are paying the cost from its reserves. $50,000. with higher-ups. facilities. highest rent on campus. This year the house’s lease in Bianco said he “would like to Excluding a subsidy, the only T h ese problem s are being The 87 occupants of the ren creased $17,000. be able” to give a rebate to the other alternative to Webster worked out, Evans said. The ovated frat house are paying According to David Bianco, residents of Webster House, ad House would have been perman building’s owner, Ernest Cutter, $330 per semester-ten dollars director of residential life, the ding that it would be “justified”. ent buildups in the dormitories, has been paying for all the reno more per semester than Chris Residence Office cannot sub A rebate will be possible only according to Bianco. -

Paul Winter Solstice Live! Mp3, Flac, Wma

Paul Winter Solstice Live! mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Jazz / Classical / Folk, World, & Country Album: Solstice Live! Country: US Released: 1993 Style: New Age, Modern Classical, Folk, Neofolk MP3 version RAR size: 1985 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1269 mb WMA version RAR size: 1976 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 690 Other Formats: VOX AUD MPC MP2 APE WAV VQF Tracklist Hide Credits Fanfare A1 Soprano Saxophone – Paul Winter Timpani – Gordon GottliebWritten-By – 0:58 Gottlieb*, Winter* Tomorrow Is My Dancing Day A2 3:07 Arranged By – Halley*Performer – The Consort*Written-By – Trad. English* Fog On The Hill Arranged By – Ní Riain*Cello – Eugene FriesenRecorded By [Wind] – Mickey A3 5:15 HoulihanSounds – Spotted OwlVoice, Liner Notes – Nóirín Ní Riain*Written-By – Trad. Irish* Shaman A4 Frame Drum – Glen VelezSoprano Saxophone – Paul Winter Written-By – 1:15 Velez*, Winter* Boon Song A5 4:51 Performer – The Consort*Voice – ÚirapurúWritten-By – Halley*, Úirapurú Buena Nueva A6 Arranged By – Andes MantaPerformer – Andes MantaWritten-By – Trad. 1:47 Ecuadorian* Nevaga A7 Arranged By – Dimitri PokrovskyVocals – Alexander Danilov, Dimitri 2:43 PokrovskyWritten-By – Trad. Russian* Highland Heaven A8 3:52 Flute – Rhonda LarsonPerformer – The Consort*Written-By – Halley* The Sparrow Arranged By – Lewis-Evans*Congas, Percussion – CaféDrums – Ted A9 5:10 MoorePerformer – The Consort*Vocals – Kecia Lewis-EvansWritten-By – Trad. American* Hodie / Good 9:28 People All Hodie 10.1 Arranged By – Halley*Performer – The Consort*Written-By – Unknown Artist Good People All 10.2 Arranged By – Halley*Performer – The Consort*Written-By – Trad. Irish* March De San Benito B1 Arranged By – Casals*Bagpipes [Gaeta] – Nando Casals*Organ – Paul 2:02 HalleyWritten-By – Trad.