Contemporary Canadian Drama And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internalizing Borderlands: the Performance of Borderlands Identity

Internalizing Borderlands: the Performance of Borderlands Identity by Megan De Roover A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Megan De Roover, December, 2012 ABSTRACT Internalizing Borderlands: the Performance of Borderlands Identity Megan De Roover Advisor: University of Guelph, 2012 Professor Martha Nandorfy In order to establish a working understanding of borders, the critical conversation must be conscious of how the border is being used politically, theoretically, and socially. This thesis focuses on the border as forcibly ensuring the performance of identity as individuals, within the context of borderlands, become embodiments of the border, and their performance of identity is created by the influence of external borders that become internalized. The internalized border can be read both as infection, a problematic divide needing to be removed, as well as an opportunity for bridging, crossing that divide. I bring together Charles Bowden (Blue Desert), Monique Mojica (Princess Pocahontas and the Blue Spots), Leslie Marmon Silko (Ceremony, Almanac of the Dead), and Guillermo Verdecchia (Fronteras Americanas) in order to develop a comprehensive analysis of the border and border identity development. In these texts, individuals are forced to negotiate their sense of self according to pre-existing cultural and social expectations on either side of the border, performing identity according to how they want to be socially perceived. The result can often be read as a fragmentation of identity, a discrepancy between how the individual feels and how they are read. I examine how identity performance occurs within the context of the border, brought on by violence and exemplified through the division between the spirit world and the material world, the manipulation of costuming and uniforms, and the body. -

Guillermo Verdecchia Theatre Artist / Teacher 46 Carus Ave

Guillermo Verdecchia Theatre Artist / Teacher 46 Carus Ave. Toronto, ON M6G 2A4 (416) 516 9574 [email protected] [email protected] Education M.A University of Guelph, School of English and Theatre Studies, August 2005 Thesis: Staging Memory, Constructing Canadian Latinidad (Supervisor: Ric Knowles) Recipient Governor-General's Gold Medal for Academic Achievement Ryerson Theatre School Acting Program 1980-82 Languages English, Spanish, French Theatre (selected) DIRECTING Two Birds, One Stone 2017 by Rimah Jabr and Natasha Greenblatt. Theatre Centre, Riser Project, Toronto The Thirst of Hearts 2015 by Thomas McKechnie Soulpepper, Theatre, Toronto The Art of Building a Bunker 2013 -15 by Adam Lazarus and Guillermo Verdecchia Summerworks Theatre Festival, Factory Theatre, Revolver Fest (Vancouver) Once Five Years Pass by Federico Garcia Lorca. National Theatre School. Montreal 2012 Ali and Ali: The Deportation Hearings 2010 by Marcus Youssef, Guillermo Verdecchia, and Camyar Chai Vancouver East Cultural Centre, Factory Theatre Toronto Guillermo Verdecchia 2 A Taste of Empire 2010 by Jovanni Sy, Cahoots Theatre Rice Boy 2009 by Sunil Kuruvilla, Stratford Festival, Stratford. The Five Vengeances 2006 by Jovanni Sy, Humber College, Toronto. The Caucasian Chalk Circle 2006 by Bertolt Brecht, Ryerson Theatre School, Toronto. Romeo and Juliet 2004 by William Shakespeare, Lorraine Kimsa Theatre for Young People, Toronto. The Adventures of Ali & Ali and the aXes of Evil 2003-07 by Youssef, Verdecchia, and Chai. Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal, Edmonton, Victoria, Seattle. Cahoots Theatre Projects 1999 – 2004 ARTISTIC DIRECTOR. Responsible for artistic planning and activities for company dedicated to development and production of new plays representative of Canada's cultural diversity. -

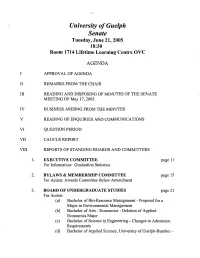

Senate Tuesday, June 21,2005 18:30 Room 1714 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC

University of Guelph Senate Tuesday, June 21,2005 18:30 Room 1714 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC AGENDA APPROVAL OF AGENDA REMARKS FROM THE CHAIR READING AND DISPOSING OF MINUTES OF THE SENATE MEETING OF May 17,2005. IV BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES v READING OF ENQUIRIES AND COMMUNICATIONS VI QUESTION PERIOD VII CAUCUS REPORT VIII REPORTS OF STANDING BOARDS AND COMMITTEES 1. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE page 11 For Information: Graduation Statistics BYLAWS & MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE page 15 For Action: Awards Committee Bylaw Amendment BOARD OF UNDERGRADUATE STUDIES page 21 For Action: (a) Bachelor of Bio-Resource Management - Proposal for a Major in Environmental Management (b) Bachelor of Arts - Economics - Deletion of Applied Economics Major (c) Bachelor of Science in Engineering - Changes to Admission Requirements (d) Bachelor of Applied Science, University of Guelph-Humber - Changes to Admission Requirements (e) Academic Schedule of Dates, 2006-2007 For Information: (0 Course, Additions, Deletions and Changes (g) Editorial Calendar Amendments (i) Grade Reassessment (ii) Readmission - Credit for Courses Taken During Rustication 4. BOARD OF GRADUATE STUDIES page 9 1 For Action: (a) Proposal for a Master of Fine Art in Creative Writing (b) Proposal for a Master of Arts in French Studies For Information: (c) Graduate Faculty Appointments (d) Course Additions, Deletions and Changes 5. COMMITTEE ON AWARDS page 177 For Information: (a) Awards Approved June 2004 - May 2005 (b) Winegard, Forster and Governor General Medal Winners 6. COMMITTEE ON UNIVERSITY PLANNING page 181 For Action: Change of Name for Department of Human Biology and Nutritional Science IX COU RE,PORT X OTHER BUSINESS XI ADJOURNMENT Please note: The Senate Executive will meet at 18:15 in Room 1713 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC just prior to Senate 1r;ne Birrell, Secretary of Senate University of Guelph Senate Tuesday, June 21": 2005 REPORT FROM THE SENATE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Chair: Al Sullivan <[email protected]~ For Information: Graduation Statistics - June 2005 Membership: A. -

The Black Drum Deaf Culture Centre Adam Pottle

THE BLACK DRUM DEAF CULTURE CENTRE ADAM POTTLE ApproximatE Running time: 1 HouR 30 minutEs INcLudes interviews before the performancE and During intermissIoN. A NOTE FROM JOANNE CRIPPS A NOTE FROM MIRA ZUCKERMANN With our focus on oppression, we forget First of all, I would like to thank the DEAF to celebrate Deaf Life. We celebrate Deaf CULTURE CENTRE for bringing me on as Life through sign language, culture and Director of The Black Drum, thereby giving arts. The Black Drum is a full exploration me the opportunity to work with a new and and celebration of our Deaf Canadian exciting international project. The project experience through our unique artistic is a completely new way of approaching practices finally brought together into one musical theatre, and it made me wonder exceptional large scale signed musical. - what do Deaf people define as music? All Almost never do we see Deaf productions Deaf people have music within them, but it that are Deaf led for a fully Deaf authentic is not based on sound. It is based on sight, innovative artistic experience in Canada. and more importantly, sign language. As We can celebrate sign language and Deaf we say - “my hands are my language, my generated arts by Deaf performers for all eyes are my ears”. I gladly accepted the audiences to enjoy together. We hope you invitation to come to Toronto, embarking have a fascinating adventure that you will on an exciting and challenging project that not easily forget and that sets the stage for I hope you all enjoy! more Deaf-led productions. -

FRIENDS and the MUNICIPAL ELECTION - YOUR Involvement Counts

September/October 2014 Volume 6, Issue 2 Mr. Dewey and Friends Newsletter of the Friends of the Guelph Public Library FRIENDS and the MUNICIPAL ELECTION - YOUR Involvement Counts The municipal election will take place on Monday, October 27, 2014. The deadline for declaring intent to stand for election has now passed, and the names of all candidates for Mayor and Council are a matter of public record. As a registered charity, the Friends of the Guelph Public Library cannot support any particular candidate for any office. The role of the group and its members and supporters is always to support and advocate for the Library in every possible way, not only concerning library buildings, but also concerning financial support to maintain our excellent information collection, excellent staff and excellent services. In the context of an election the role of the Friends is to work tirelessly to ensure that voters have full and accurate information about the Library when they examine candidates’ platforms and make their voting choices. It is important that voters select candidates with vision and a broad understanding of the ram- ifications of their platforms. Your role as a supporter of the Library is to inform yourself and be prepared to question candidates and supply accurate information when you encounter misin- formation or uninformed voters between now and election day. Go to all-candidates meetings and ask questions about the Library’s future. For more about library-related issues, there is a wealth of information at Kitty Pope’s blog on the Library website: http://kittysonapositivenote.wordpress.com/. -

UNIVERSIDAD TECNOLÓGICA NACIONAL Facultad Regional

UNIVERSIDAD TECNOLÓGICA NACIONAL Facultad Regional Concepción del Uruguay Licenciatura en Lengua Inglesa MULTIPLE BORDER IDENTITIES AND CODE-SWITCHING. THE CASE OF FRONTERAS AMERICANAS/ AMERICAN BORDERS BY GUILLERMO VERDECCHIA Tesis presentada por Marcela Paula GHIGLIONE como requisito parcial para la obtención del grado académico de Licenciada en Lengua Inglesa Directora de Tesis: Dra. María Laura SPOTURNO 2016 Concepción del Uruguay, Entre Ríos, Argentina For my parents, Adriana y Jorge, with all respect For my love, Miguel, con todo mi corazón. 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to express my profound gratitude to María Laura Spoturno, my supervisor, for her stimulating discussion and questioning of many of the issues presented in this thesis. Without those invaluable suggestions and continuous encouragement this study could not have been completed. I would also like to acknowledge the coordinator of the career “Licenciatura en Lengua Inglesa”, Paula Aguilar, for her enthusiasm and constant guiding. My third debt of gratitude is to the staff of teachers who shared with us their invaluable insights, enriching comments and materials. Undoubtedly, they have left their mark on both my professional and personal development. Many people have also provided helpful input on this paper, at various stages. For their thoughtful and detailed suggestions through emails, I would particularly like to thank: Carol Myers-Scotton, Guillermo Verdecchia and Pieter Muysken. I also extend my thanks to Rocio Naef who shared with me her valuable comments on numerous revised drafts of this paper. I would like to express my appreciation to Luz Aranda, Celeste Rojas, Yamil Barrios, Tamara Romero, Luciana Sanzberro, Hebe Bouvet and my cousin, Daniela Koczwara, who provided me with helpful academic and technical advice. -

Camellia Koo Curriculum Vitae

CAMELLIA KOO CURRICULUM VITAE Please Contact Ian Arnold, Artist Representative @ Catalyst TCM 15 Old Primrose Lane, Toronto, ON M5A 4T1 Tel: 1-416-568-8673 [email protected] Opera & Ballet Design Set Treemonisha Weyni Mengesha Volcano/Stanford/SFO postponed Set Candide Joel Ivany Edmonton Opera 2020 Set & Costume Jacqueline Michael Mori Tapestry New Opera 2020 Set Rigoletto Rob Harriot Edmonton Opera 2019 Costume La Bohème Mary Birnbaum Santa Fe Opera Set Shanawdithit M. Mori/Y. Nolan Tapestry New Opera Set Hansel and Gretel Rob Harriot Edmonton Opera Set & Costume La Bohème Maria Lamont Pacific Opera Victoria 2018 Set HMS Pinafore Rob Harriot Edmonton Opera Set & Costume Turandot Dmitri Bertman Helikon Opera, Russia 2017 Set & Costume Simon Boccanegra Glynis Leyshon Pacific Opera Victoria 2016 Set Rocking Horse Winner Michael Mori Tapestry New Opera Set & Costume Maria Stuarda Maria Lamont Edmonton Opera Set Carmen Maria Lamont Edmonton Opera Set & Costume Sleeping Beauty Bengt Jorgen Ballet Jorgen Canada 2015 Set Pelléas et Mélisande Joel Ivany Against the Grain 2014 Costume Design Macbeth Joel Ivany Minnesota Opera Set & Costume Marilyn Forever Joel Ivany Aventa Ensemble 2013 Set & Costume Tales of Hoffman Joel Ivany Edmonton Opera Set & Costume Songs of Love and War Tim Albery U of T Opera Division 2012 Set Turn of the Screw Joel Ivany Against the Grain Theatre Set & Costume Maria Stuarda Maria Lamont Pacific Opera Victoria Set & Costume The Lighthouse Tim Albery Boston Lyric Opera Set La Bohème Joel Ivany Against the Grain Theatre -

A Comparative Literary Analysis Diplomarbeit

“To choose is to go wrong”: The Representation of Borderland Identities: A Comparative Literary Analysis Diplomarbeit Zum Erlangen des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von David SCHNEEBACHER am Institut für Amerikanistik Begutachterin: Assoz. Prof. Mag. Dr.phil. Ulla Kriebernegg Graz, 2021 Ehrenwörtliche Erklärung Ich erkläre ehrenwörtlich, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die angegebenen Quellen nicht benutzt und die den Quellen wörtlich oder inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Die Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form keiner anderen inländischen oder ausländischen Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegt und auch noch nicht veröffentlicht. Die vorliegende Fassung entspricht der eingereichten elektronischen Version. Datum: Unterschrift: ......................................... .......................................... Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude towards a number of people, who have helped me extensively through my time as a student at the University of Graz, and my diploma thesis. First of all, I want to thank my mentor Dr. Ulla Kriebernegg for being so supportive before and during my quest of writing this paper. Her remarkable expertise in the field, as well as her positivity, despite her busy schedule have taught me a lot, and I will forever be grateful for her support. In addition, I want to thank my friends Red, Wolfi, Gernot, Bernd, Tauni, Matthias, and Thomas for their mental support through all these years, especially towards the end of my studies. Their infinitely positive attitude, as well as their unconditional friendship is unmatched, and will always stay with me. The biggest thank you however, is reserved for my family, especially my parents. -

Poetics of Denial Expressions of National Identity and Imagined Exile in English�Canadian and Romanian Dramas

Poetics of Denial Expressions of National Identity and Imagined Exile in English-Canadian and Romanian Dramas by DIANA MARIA MANOLE A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Centre for Study of Drama University of Toronto © Copyright by Diana Maria Manole 2010 Poetics of Denial Expressions of National Identity and Imagined Exile in English-Canadian and Romanian Dramas Diana Maria Manole Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Centre for Study of Drama University of Toronto 2010 Abstract After the change of their country’s political and international statuses, post-colonial and respectively post-communist individuals and collectives develop feelings of alienation and estrangement that do not involve physical dislocation. Eventually, they start imagining their national community as a collective of individuals who share this state. Paraphrasing Benedict Anderson’s definition of the nation as an “imagined community,” this study identifies this process as “imagined exile,” an act that temporarily compensates for the absence of a metanarrative of the nation during the post-colonial and post-communist transitions. This dissertation analyzes and compares ten English Canadian and Romanian plays, written between 1976 and 2004, and argues that they function as expressions and agents of post-colonial and respectively post-communist imagined exile, helping their readers and audiences overcome the identity crisis and regain the feeling of belonging to a national community. Chapter 1 explores the development of major theoretical concepts, such as ii nation, national identity, national identity crisis, post-colonialism, and post-communism. Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 analyze dramatic rewritings of historical events, in 1837: The Farmers’ Revolt by the theatre Passe Muraille with Rick Salutin as dramaturge, and A Cold by Marin Sorescu, and of past political leaders, in Sir John, Eh! by Jim Garrard and A Day from the Life of Nicolae Ceausescu by Denis Dinulescu. -

Soulpepper 2016 AGM & Campaign Update.Indd

Media Contact: Katie Saunoris, Publicist !"#.$%&.#$#! x."!# katie @soulpepper.ca MEDIA RELEASE SOULPEPPER 2016: 2015 AGM & A NATIONAL CIVIC THEATRE UPDATE A Creative Capital Campaign Update & News on a National Commissioning Project, Touring, New Artistic Residencies, the !"#$-!"#% Soulpepper Academy and More! Toronto, ON – April $", $%"#: Today Soulpepper Theatre Company celebrated its $%"' season at its annual general meeting (AGM), and made updates to its fi ve-year strategic initiative to expand the scope of the company’s mission as a National Civic Theatre. LAST YEAR’S HIGHLIGHTS As part of Soulpepper’s AGM, results of its $%"' season were shared. Last year under the leadership of Artistic Director Albert Schultz and Executive Director Leslie Lester, the company presented '+! events in theatre, music, and festivals with a total attendance of /',/"$. With an operating budget of $/./ million, Soulpepper provided employment to $'' artists and ## full-time and part-time staff . Selected highlights: • !,'+' youth were reached through education outreach and school bookings. • The company made three audio album recordings of productions available for purchase, and made all of its Cabaret recordings available for free on SoundCloud. • Young Family Director of Design Lorenzo Savoini and Soulpepper’s production Of Human Bondage were chosen to represent Canada at the prestigious Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space, and Vern Thiessen’s Of Human Bondage adaptation was published by Playwrights Canada Press. • Soulpepper enhanced its -

Blood Wedding

PLAYBILL BLOOD WEDDING BLOOD WEDDING FederiCO GarCÍA LorCA Translated by GuillerMO VerdeCCHia ORIGINAL SCore BY ANDREW PENNER }{ ApproximAte running time: 1 hour & 30 minutes there will be no intermission ARTIST NOTE: ERIN BRANDENBURG My first attempt to understand Blood Wedding tragedy. In the end we are our own worst was through translation. From one language jailers. Lorca’s universe does not provide to another, one country to another. And a moral lesson; there are no simple answers. before a word was written down for this It is the struggle that is important and production we began a translation in sound, creates the poetry. To live is to dance with in melody, in rhythm, tempo and movement. your demons and in the process throw your It was like a folk song, a murder ballad heart at the horns. passed down through the years and across continents and each time it is performed is It is a great pleasure to open Blood Wedding reborn for that time and that moment. The across the hall from The Just, shows Frank story haunts you because you’ve heard it Cox O’Connell and I have worked on together before, but in it there’s a struggle for some- and alongside each other for the past two thing deeper that grabs hold and won’t let go. years. These shows have shared a conversation and development here at Soulpepper. Thank Blood Wedding is the story of a wedding. And you to Daniel Brooks for his guidance and weddings involve families and communities mentorship throughout the process. -

The Seagull Anton Chekhov Adapted by Simon Stephens

THE SEAGULL ANTON CHEKHOV ADAPTED BY SIMON STEPHENS major sponsor & community access partner WELCOME TO THE SEAGULL The artists and staff of Soulpepper and the Young Centre for the Performing Arts acknowledge the original caretakers and storytellers of this land – the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, and Wendat First Nation, and The Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation who are part of the Anishinaabe Nation. We commit to honouring and celebrating their past, present and future. “All around the world and throughout history, humans have acted out the stories that are significant to them, the stories that are central to their sense of who they are, the stories that have defined their communities, and shaped their societies. When we talk about classical theatre we want to explore what that means from the many perspectives of this city. This is a celebration of our global canon.” – Weyni Mengesha, Soulpepper’s Artistic Director photo by Emma Mcintyre Partners & Supporters James O’Sullivan & Lucie Valée Karrin Powys-Lybbe & Chris von Boetticher Sylvia Soyka Kathleen & Bill Troost 2 CAST & CREATIVE TEAM Cast Ghazal Azarbad Stuart Hughes Gregory Prest Marcia Hugo Boris Oliver Dennis Alex McCooeye Paolo Santalucia Peter Sorin Simeon Konstantin Raquel Duffy Kristen Thomson Sugith Varughese Pauline Irina Leo Hailey Gillis Dan Mousseau Nina Jacob Creative Team Daniel Brooks Weyni Mengesha Megan Woods Director Artistic Director Associate Production Manager Thomas Ryder Payne Emma Stenning Corey MacVicar Sound Designer Executive Director Associate Technical Director Frank Cox-O’Connell Tania Senewiratne Nik Murillo Associate Director Executive Producer Marketer Gregory Sinclair Mimi Warshaw Audio Producer Producer Matt Rideout Maricris Rivera Lead Audio Engineer Producing Assistant Thank You To Michelle Monteith, Daren A.