UNIVERSIDAD TECNOLÓGICA NACIONAL Facultad Regional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union's

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union’s East Border Brie, Mircea and Horga, Ioan and Şipoş, Sorin University of Oradea, Romania 2011 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/44082/ MPRA Paper No. 44082, posted 31 Jan 2013 05:28 UTC ETHNICITY, CONFESSION AND INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE AT THE EUROPEAN UNION EASTERN BORDER ETHNICITY, CONFESSION AND INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE AT THE EUROPEAN UNION EASTERN BORDER Mircea BRIE Ioan HORGA Sorin ŞIPOŞ (Coordinators) Debrecen/Oradea 2011 This present volume contains the papers of the international conference Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union‟s East Border, held in Oradea between 2nd-5th of June 2011, organized by Institute for Euroregional Studies Oradea-Debrecen, University of Oradea and Department of International Relations and European Studies, with the support of the European Commission and Bihor County Council. CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY STUDIES Mircea BRIE Ethnicity, Religion and Intercultural Dialogue in the European Border Space.......11 Ioan HORGA Ethnicity, Religion and Intercultural Education in the Curricula of European Studies .......19 MINORITY AND MAJORITY IN THE EASTERN EUROPEAN AREA Victoria BEVZIUC Electoral Systems and Minorities Representations in the Eastern European Area........31 Sergiu CORNEA, Valentina CORNEA Administrative Tools in the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Ethnic Minorities .............................................................................................................47 -

Internalizing Borderlands: the Performance of Borderlands Identity

Internalizing Borderlands: the Performance of Borderlands Identity by Megan De Roover A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Megan De Roover, December, 2012 ABSTRACT Internalizing Borderlands: the Performance of Borderlands Identity Megan De Roover Advisor: University of Guelph, 2012 Professor Martha Nandorfy In order to establish a working understanding of borders, the critical conversation must be conscious of how the border is being used politically, theoretically, and socially. This thesis focuses on the border as forcibly ensuring the performance of identity as individuals, within the context of borderlands, become embodiments of the border, and their performance of identity is created by the influence of external borders that become internalized. The internalized border can be read both as infection, a problematic divide needing to be removed, as well as an opportunity for bridging, crossing that divide. I bring together Charles Bowden (Blue Desert), Monique Mojica (Princess Pocahontas and the Blue Spots), Leslie Marmon Silko (Ceremony, Almanac of the Dead), and Guillermo Verdecchia (Fronteras Americanas) in order to develop a comprehensive analysis of the border and border identity development. In these texts, individuals are forced to negotiate their sense of self according to pre-existing cultural and social expectations on either side of the border, performing identity according to how they want to be socially perceived. The result can often be read as a fragmentation of identity, a discrepancy between how the individual feels and how they are read. I examine how identity performance occurs within the context of the border, brought on by violence and exemplified through the division between the spirit world and the material world, the manipulation of costuming and uniforms, and the body. -

Competitive Preferences and Ethnicity: Experimental Evidence from Bangladesh

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 10682 Competitive Preferences and Ethnicity: Experimental Evidence from Bangladesh Abu Siddique Michael Vlassopoulos MARCH 2017 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 10682 Competitive Preferences and Ethnicity: Experimental Evidence from Bangladesh Abu Siddique University of Southampton Michael Vlassopoulos University of Southampton and IZA MARCH 2017 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 10682 MARCH 2017 ABSTRACT Competitive Preferences and Ethnicity: Experimental Evidence from Bangladesh* In many countries, ethnic minorities have a persistent disadvantageous socioeconomic position. We investigate whether aversion to competing against members of the ethnically dominant group could be a contributing factor to this predicament. -

Between Stereotype and Reality of the Ethnic Groups in Malaysia

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 10, No. 16, Youth and Community Wellbeing: Issues, Challenges and Opportunities for Empowerment V2. 2020, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2020 HRMARS Images in the Human Mind: Between Stereotype and Reality of the Ethnic Groups in Malaysia Rohaizahtulamni Radzlan, Mohd Roslan Rosnon & Jamilah Shaari To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i16/9020 DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i16/9020 Received: 24 October 2020, Revised: 18 November 2020, Accepted: 30 November 2020 Published Online: 17 December 2020 In-Text Citation: (Radzlan et al., 2020) To Cite this Article: Radzlan, R., Rosnon, M. R., & Shaari, J. (2020). Images in the Human Mind: Between Stereotype and Reality of the Ethnic Groups in Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 10(16), 412–422. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Special Issue: Youth and Community Wellbeing: Issues, Challenges and Opportunities for Empowerment V2, 2020, Pg. 412 - 422 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 412 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. -

Guillermo Verdecchia Theatre Artist / Teacher 46 Carus Ave

Guillermo Verdecchia Theatre Artist / Teacher 46 Carus Ave. Toronto, ON M6G 2A4 (416) 516 9574 [email protected] [email protected] Education M.A University of Guelph, School of English and Theatre Studies, August 2005 Thesis: Staging Memory, Constructing Canadian Latinidad (Supervisor: Ric Knowles) Recipient Governor-General's Gold Medal for Academic Achievement Ryerson Theatre School Acting Program 1980-82 Languages English, Spanish, French Theatre (selected) DIRECTING Two Birds, One Stone 2017 by Rimah Jabr and Natasha Greenblatt. Theatre Centre, Riser Project, Toronto The Thirst of Hearts 2015 by Thomas McKechnie Soulpepper, Theatre, Toronto The Art of Building a Bunker 2013 -15 by Adam Lazarus and Guillermo Verdecchia Summerworks Theatre Festival, Factory Theatre, Revolver Fest (Vancouver) Once Five Years Pass by Federico Garcia Lorca. National Theatre School. Montreal 2012 Ali and Ali: The Deportation Hearings 2010 by Marcus Youssef, Guillermo Verdecchia, and Camyar Chai Vancouver East Cultural Centre, Factory Theatre Toronto Guillermo Verdecchia 2 A Taste of Empire 2010 by Jovanni Sy, Cahoots Theatre Rice Boy 2009 by Sunil Kuruvilla, Stratford Festival, Stratford. The Five Vengeances 2006 by Jovanni Sy, Humber College, Toronto. The Caucasian Chalk Circle 2006 by Bertolt Brecht, Ryerson Theatre School, Toronto. Romeo and Juliet 2004 by William Shakespeare, Lorraine Kimsa Theatre for Young People, Toronto. The Adventures of Ali & Ali and the aXes of Evil 2003-07 by Youssef, Verdecchia, and Chai. Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal, Edmonton, Victoria, Seattle. Cahoots Theatre Projects 1999 – 2004 ARTISTIC DIRECTOR. Responsible for artistic planning and activities for company dedicated to development and production of new plays representative of Canada's cultural diversity. -

Social Cognition and the Impact of Race/Ethnicity on Clinical Decision Making

Social Cognition and the Impact of Race/Ethnicity on Clinical Decision Making Author: Deborah Washington Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/3149 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2012 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. SOCIAL COGNITION AND 1 Running head: SOCIAL COGNITION AND THE IMPACT OF RACE AND SOCIAL COGNITION AND THE IMPACT OF RACE AND ETHNICITY ON CLINICAL DECISION MAKING Deborah Washington, PhD, RN Boston College © copyright by DEBORAH WASHINGTON 2012 SOCIAL COGNITION AND 2 Abstract Social Cognition and the Impact of Race and Ethnicity on Clinical Decision Making Most literature reflects the persistent existence of unequal treatment in the care provided to ethnic and racial minorities. Comparatively little about ethnic bias in the literature goes beyond the retrospective study as the most frequently encountered method of inquiry. Access to providers and the ability to pay only provide partial explanation in the known data. A more controversial hypothesis is the one offered in this dissertation. This qualitative research explored the cognitive processes of ethnic bias as a phenomenon in clinical decision making. The method was a simulation that captured events as they occurred with a sample of nurse participants. The racial and ethnically related cognitive content of participants was evoked through the interactive process of playing a board game. Immediately following that activity, a video vignette of an ambiguous pain management situation involving an African American male was viewed by each nurse who was then asked to make a “treat” or “not treat” clinical decision. -

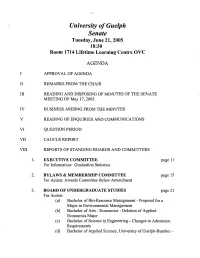

Senate Tuesday, June 21,2005 18:30 Room 1714 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC

University of Guelph Senate Tuesday, June 21,2005 18:30 Room 1714 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC AGENDA APPROVAL OF AGENDA REMARKS FROM THE CHAIR READING AND DISPOSING OF MINUTES OF THE SENATE MEETING OF May 17,2005. IV BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES v READING OF ENQUIRIES AND COMMUNICATIONS VI QUESTION PERIOD VII CAUCUS REPORT VIII REPORTS OF STANDING BOARDS AND COMMITTEES 1. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE page 11 For Information: Graduation Statistics BYLAWS & MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE page 15 For Action: Awards Committee Bylaw Amendment BOARD OF UNDERGRADUATE STUDIES page 21 For Action: (a) Bachelor of Bio-Resource Management - Proposal for a Major in Environmental Management (b) Bachelor of Arts - Economics - Deletion of Applied Economics Major (c) Bachelor of Science in Engineering - Changes to Admission Requirements (d) Bachelor of Applied Science, University of Guelph-Humber - Changes to Admission Requirements (e) Academic Schedule of Dates, 2006-2007 For Information: (0 Course, Additions, Deletions and Changes (g) Editorial Calendar Amendments (i) Grade Reassessment (ii) Readmission - Credit for Courses Taken During Rustication 4. BOARD OF GRADUATE STUDIES page 9 1 For Action: (a) Proposal for a Master of Fine Art in Creative Writing (b) Proposal for a Master of Arts in French Studies For Information: (c) Graduate Faculty Appointments (d) Course Additions, Deletions and Changes 5. COMMITTEE ON AWARDS page 177 For Information: (a) Awards Approved June 2004 - May 2005 (b) Winegard, Forster and Governor General Medal Winners 6. COMMITTEE ON UNIVERSITY PLANNING page 181 For Action: Change of Name for Department of Human Biology and Nutritional Science IX COU RE,PORT X OTHER BUSINESS XI ADJOURNMENT Please note: The Senate Executive will meet at 18:15 in Room 1713 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC just prior to Senate 1r;ne Birrell, Secretary of Senate University of Guelph Senate Tuesday, June 21": 2005 REPORT FROM THE SENATE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Chair: Al Sullivan <[email protected]~ For Information: Graduation Statistics - June 2005 Membership: A. -

The Black Drum Deaf Culture Centre Adam Pottle

THE BLACK DRUM DEAF CULTURE CENTRE ADAM POTTLE ApproximatE Running time: 1 HouR 30 minutEs INcLudes interviews before the performancE and During intermissIoN. A NOTE FROM JOANNE CRIPPS A NOTE FROM MIRA ZUCKERMANN With our focus on oppression, we forget First of all, I would like to thank the DEAF to celebrate Deaf Life. We celebrate Deaf CULTURE CENTRE for bringing me on as Life through sign language, culture and Director of The Black Drum, thereby giving arts. The Black Drum is a full exploration me the opportunity to work with a new and and celebration of our Deaf Canadian exciting international project. The project experience through our unique artistic is a completely new way of approaching practices finally brought together into one musical theatre, and it made me wonder exceptional large scale signed musical. - what do Deaf people define as music? All Almost never do we see Deaf productions Deaf people have music within them, but it that are Deaf led for a fully Deaf authentic is not based on sound. It is based on sight, innovative artistic experience in Canada. and more importantly, sign language. As We can celebrate sign language and Deaf we say - “my hands are my language, my generated arts by Deaf performers for all eyes are my ears”. I gladly accepted the audiences to enjoy together. We hope you invitation to come to Toronto, embarking have a fascinating adventure that you will on an exciting and challenging project that not easily forget and that sets the stage for I hope you all enjoy! more Deaf-led productions. -

FRIENDS and the MUNICIPAL ELECTION - YOUR Involvement Counts

September/October 2014 Volume 6, Issue 2 Mr. Dewey and Friends Newsletter of the Friends of the Guelph Public Library FRIENDS and the MUNICIPAL ELECTION - YOUR Involvement Counts The municipal election will take place on Monday, October 27, 2014. The deadline for declaring intent to stand for election has now passed, and the names of all candidates for Mayor and Council are a matter of public record. As a registered charity, the Friends of the Guelph Public Library cannot support any particular candidate for any office. The role of the group and its members and supporters is always to support and advocate for the Library in every possible way, not only concerning library buildings, but also concerning financial support to maintain our excellent information collection, excellent staff and excellent services. In the context of an election the role of the Friends is to work tirelessly to ensure that voters have full and accurate information about the Library when they examine candidates’ platforms and make their voting choices. It is important that voters select candidates with vision and a broad understanding of the ram- ifications of their platforms. Your role as a supporter of the Library is to inform yourself and be prepared to question candidates and supply accurate information when you encounter misin- formation or uninformed voters between now and election day. Go to all-candidates meetings and ask questions about the Library’s future. For more about library-related issues, there is a wealth of information at Kitty Pope’s blog on the Library website: http://kittysonapositivenote.wordpress.com/. -

Ethnic Stereotypes – Impediments Or Enhancers of Social Cognition?

Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Philologica, 3, 2 (2011) 134-155 Ethnic Stereotypes – Impediments or Enhancers of Social Cognition? Zsuzsanna AJTONY Sapientia Hungarian University of Transylvania Department of Humanities [email protected] Abstract. This paper presents a brief summary of the recent literature on stereotypes according to social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner 1986). It offers a comparison of related concepts such as prejudice (Gadamer 1984) and attitude (Cseresnyési 2004) and relies on stereotype definition developed by Hilton and Hippel (1996). It gives a survey of stereotype manifestation, formation, maintenance and change, focusing on social and ethnic stereotypes, their background variables, transmitting mechanisms and mediating variables. The last part of the paper discusses different linguistic means of expressing ethnicity concluding that stereotypes act as ever-extendable schemas as opposed to prototypes, defined as best examples of a category. Keywords: linguistic and social categories, ethnic identity, schema theory, prototypes vs. stereotypes 1. Introduction This paper is dedicated to a deeper insight into the nature of stereotypes – as forms of social cognition. First the nature of stereotypes is explored, in their generic sense, defining them from a cognitive approach, experimental psychology. In order to do that, they need to be clearly distinguished from prototypes, as defined by prototype theory (Rosch 1975, Lakoff 1987). This is the contents of sections 2 – 5, also including a short -

State of the Art Volume 9 Issue 1 2016

PSYCHOLOGY IN RUSSIA: STATE OF THE ArT Volume 9 Issue 1 2016 Editorial 2 SpECIAL ISSUE “MULTICULTURALISM AND INTERCULTURAL RELATIONS: COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS” Multiculturalism and intercultural relations: Regional cases Comparative analysis of Canadian multiculturalism policy and the multiculturalism policies of other countries 4 Berry J. Is multiculturalism in Russia possible? Intercultural relations in North Ossetia-Alania 24 Galyapina V. N., Lebedeva N. M. Intercultural relations in Russia and Latvia: the relationship between contact and cultural security 41 Lebedeva N. M., Tatarko A. N., Berry J. Intercultural relations in Kabardino-Balkaria: Does integration always lead to subjective well-being? 57 Lepshokova Z. Kh., Tatarko A. N. Ethno-confessional identity and complimentarity in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 74 Mikhailova V. V., Nadkin V. B. The representation of love among Brazilians, Russians and Central Africans: A comparative analysis 84 Pilishvili T. S., Koyanongo E. Assimilation or integration: Similarities and differences between acculturation attitudes of migrants from Central Asia and Russians in Central Russia 98 Ryabichenko T. A., Lebedeva N. M. Intercultural relationships in the students’ environment Ethnoreligious attitudes of contemporary Russian students toward labor migrants as a social group 112 Abakumova I. V., Boguslavskaya V. F., Grishina A. V. Ethnopsychological aspects of the meaning-of-life and value orientations of Armenian and Russian students 121 Berberyan A. S., Berberyan H. S. Readiness for interaction with inoethnic subjects of education and ethnic worldview 138 Valiev R. A., Valieva T. V., Maksimova L.A., Karimova V. G. Multiculturalism in public and private spaces On analyzing the results of empirical research into the life-purpose orientations of adults of various ethnic identities and religious affiliations 155 Abakumova I. -

65 Ethnicity, Stereotypes and Ethnic Movements in Nepal

Crossing the Border: International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies ISSN 2350-8752(P) Volume 1; Number 1; 15 December 2013 ISSN 2350-8922 (O) ETHNICITY, STEREOTYPES AND ETHNIC MOVEMENTS IN NEPAL Prakash Upadhyay, Ph.D., Assoc. Prof. of Anthropology Tribhuvan University, Prithvi Narayan Campus, Pokhara [email protected] ABSTRACT Liberal political environment, globalization, urbanization and migration amid the hectic politi- cal process of constitution dra! ing trapped in the issue of federalism and inclusion made the issue of ethnicity more debatable in Nepal. New ethnic identities were forged, new associations set up, and new allegations made in social, political, geographical and economic sectors for the reorganization of the country. Ethnicity does not always shoot out from antique tradition or nationality, however is fashioned, socially/culturally constructed, adapted, recreated, or even manufactured in the modern society. For that reason, it is necessary to see ethnicity as process i.e. making of boundaries, " uidity of boundaries as well as the sti# ening of boundaries, variations in categorization and identi$ cation among groups in di# erent times and places. Hence, State reorganization on the basis of capricious ethnic and religious history and so on will lead to confusion, disintegration and mayhem. % e bases of successful Indian federation are characterized by geographic diversities, regional, cultures, and linguistic features. % e $ nest inclusive democratic federalism, one could anticipate for in Nepal is some form