Perianesthetic Management of Laryngospasm in Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

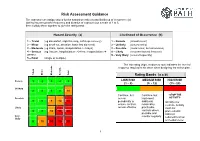

Risk Assessment Guidance

Risk Assessment Guidance The assessor can assign values for the hazard severity (a) and likelihood of occurrence (b) (taking into account the frequency and duration of exposure) on a scale of 1 to 5, then multiply them together to give the rating band: Hazard Severity (a) Likelihood of Occurrence (b) 1 – Trivial (eg discomfort, slight bruising, self-help recovery) 1 – Remote (almost never) 2 – Minor (eg small cut, abrasion, basic first aid need) 2 – Unlikely (occurs rarely) 3 – Moderate (eg strain, sprain, incapacitation > 3 days) 3 – Possible (could occur, but uncommon) 4 – Serious (eg fracture, hospitalisation >24 hrs, incapacitation >4 4 – Likely (recurrent but not frequent) weeks) 5 – Very likely (occurs frequently) 5 – Fatal (single or multiple) The risk rating (high, medium or low) indicates the level of response required to be taken when designing the action plan. Trivial Minor Moderate Serious Fatal Rating Bands (a x b) Remote 1 2 3 4 5 LOW RISK MEDIUM RISK HIGH RISK (1 – 8) (9 - 12) (15 - 25) Unlikely 2 4 6 8 10 Continue, but Continue, but -STOP THE Possible review implement ACTIVITY- 3 6 9 12 15 periodically to additional Identify new ensure controls reasonably controls. Activity Likely remain effective practicable must not controls where 4 8 12 16 20 proceed until possible and risks are Very monitor regularly reduced to a low likely 5 10 15 20 25 or medium level 1 Risk Assessments There are a number of explanations needed in order to understand the process and the form used in this example: HAZARD: Anything that has the potential to cause harm. -

(BSL-1) Inspection Checklist Agents

PI: Lab Contact: Room(s): Inspected by: Research and Occupational Safety Date: Biological Safety Level 1 (BSL-1) Inspection Checklist Agents: References: CDC/NIH Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules UW Biosafety Manual Hazard Communication Notes Exposure Response Poster is in lab; lab staff is aware of proper procedures. yes no NA Facility Access to the lab is limited or restricted at the discretion of the PI when experiments are in progress. yes no NA The lab is designed so that it can be easily cleaned. Lab furniture is sturdy. Spaces between benches, cabinets, yes no NA and equipment are accessible for cleaning. Benchtops are impervious to water; chairs are covered with non-fabric material; no rugs or carpet are present. yes no NA Each lab contains a sink for hand washing. yes no NA Personnel wash their hands after handling biohazardous materials or animals and before exiting the yes no NA laboratory. Hand soap and paper towels are available at the sink. If the lab has windows that open, they are fitted with fly screens. yes no NA Exposure Control Smoking, chewing gum, handling contacts, applying cosmetics is not allowed in lab. No food or drinks yes no NA consumed or stored in the lab. Personnel wear clothing that covers the skin on legs (long pants or skirts) and closed-toe shoes. yes no NA Appropriate PPE (personal protective equipment) is readily available. yes no NA Work surfaces are decontaminated once a day (following work) and after any spill of viable material. -

Laryngospasm Caused by Removal of Nasogastric Tube After Tracheal Extubation: Case Report

Yanaka A, et al. J Anesth Clin Care 2021, 8: 061 DOI: 10.24966/ACC-8879/100061 HSOA Journal of Anesthesia & Clinical Care Case Report pCO2: Partial pressure of carbon dioxide pO : Partial pressure of oxygen Laryngospasm Caused by 2 mmHg: Millimeter of mercury Removal of Nasogastric Tube mg/dl: Milligram per deciliter mmol/L: Millimole per litter after Tracheal Extubation: Case Introduction Report Background Laryngospasm (spasmodic closure of the larynx) is an airway Ayumi Yanaka1 and Takuo Hoshi2* complication that may occur when a patient emerges from general 1Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Ibaraki Prefectur- anesthesia. It is a protective reflex, but may sometimes result in al Central Hospital, Japan pulmonary aspiration, pulmonary edema, arrhythmia and cardiac 2Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Clinical and Edu- arrest [1]. It does not often cause severe hypoxemia in the patient, and cational Training Center, Tsukuba University Hospital, Japan our review of the literature revealed no previous reports of such cases that cause of the laryngospasm was the removal of nasogastric tube. Here, we describe this significant adverse event in a case and suggest Abstract ways to lessen the possibility of its occurrence. We obtained written informed consent for publication of this case report from the patient. Background: We report a case of laryngospasm during nasogastric tube removal. Laryngospasm is a severe airway complication after Case report surgery and there have been no reports associated with the removal of nasogastric tubes. A 54-year-old woman height, 157 cm; weight, 61 kg underwent abdominal surgery (partial hepatectomy with right partial Case Report: After abdominal surgery, the patient was extubated the tracheal tube, and was removed the nasogastric tube. -

Operational Risk Management Guide

OPERATIONAL RISK MANAGEMENT GUIDE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE 2020 Last Updated 02/26/2020 RISK MANAGEMENT COUNCIL IN COOPERATION WITH THE OFFICE OF SAFETY & OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH and THE NATIONAL AVIATION SAFETY COUNCIL Contents Contents ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................................. i Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... 1 What is Operational Risk Management? ................................................................................................................... 1 The Terminology of ORM ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Principles of ORM Application ........................................................................................................................................... 6 The Five-Step ORM Process ................................................................................................................................................ 7 Step 1: Identify Hazards .................................................................................................................................................. -

Hanging, Strangulation and Other Forms of Asphyxiation

Hanging, Strangulation and Other Forms of Asphyxiation Steven Campman, M.D. Chief Deputy Medical Examiner San Diego County 16 October 2018 Overview • Terms • Other forms of asphyxiation • Neck Compression –Hanging –Strangulation Asphyxia • The physical and chemical state caused by the interference with normal respiration. • A condition that interferes with cells ability to receive or use oxygen. General Effects • Decrease and cessation of breathing • Leads to bradycardia and eventually asystole • Slowing, then flattening of the EEG Many Terms • Gag: to obstruct the mouth • Choke: to compress or otherwise obstruct the airway • Strangle: asphyxia by external compression of the throat •Throttle: same as strangle; especially manual strangulation • Garrote: strangle; especially ligature strangulation •Burking: chest compression and smothering. Many Terms • Suffocate: (broad term) a layperson’s synonym for asphyxiation, sometimes used to mean smother. • Choke –a layperson’s term for strangulation –A medical term for internal blocking of the airway Classification of Asphyxia Neck Airway Mechanical Exclusion Compression Obstruction Asphyxia of Oxygen Airway Obstruction •Smothering •Gagging •Choking (laryngeal blockage, aspiration, food bolus) Suicide Kit Choking Internal obstruction of airway • Mouth: gag • Larynx or trachea: obstruction by foreign body, “café coronary,” anaphylaxis, laryngospasm, epiglottitis • Tracheobronchial tree: aspiration, drowning FOOD BOLUS Anaphylaxis from Wasp Stings Mechanical Asphyxia Ability to breath is compromised -

UKRIO Code of Practice for Research

UK Research Integrity Office Code of Practice For Research Promoting good practice and preventing misconduct Code of Practice for Research © 2009 and 2021 UK Research Integrity Office Recommended Checklist for Researchers The Checklist lists the key points of good practice for a research project and is applicable to all subject areas. More detailed guidance is available in Section 3. A PDF version is available from our website. Code of Practice for Research © 2009 and 2021 UK Research Integrity Office Contents RECOMMENDED CHECKLIST FOR RESEARCHERS .............................. inside front cover 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 2. PRINCIPLES ....................................................................................................................... 4 3. STANDARDS FOR ORGANISATIONS AND RESEARCHERS ......................................... 6 3.1 General guidance on good practice in research ........................................................ 6 3.2 Leadership and supervision ........................................................................................ 7 3.3 Training and mentoring ................................................................................................ 7 3.4 Research design ........................................................................................................... 8 3.5 Collaborative working ................................................................................................. -

CONFINED SPACE ENTRY PERMIT Name(S) Or Person(S) Testing

CONFINED SPACE ENTRY PERMIT Confined Space Location/Description/ID Number Date: ______________________________________________________________________________________ Purpose of Entry _____________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________ Time In: ______________ Permit Canceled Time: _____________________________________ Time Out: ____________ Reason Permit Canceled: ___________________________________ Supervisor: ___________________________________________________________________________ Rescue and Emergency Services- Hazards of Confined Yes No Special Requirements Yes No Space Oxygen deficiency Hot Work Permit Required Combustible gas/vapor Lockout/Tagout Combustible dust Lines broken, capped, or blanked Carbon Monoxide Purge-flush and vent Hydrogen Sulfide Secure Area-Post and Flag Toxic gas/vapor Ventilation Toxic fumes Other- List: Skin- chemical hazards Special Equipment Electrical hazard Breathing apparatus- respirator Mechanical hazard Escape harness required Engulfment hazard Tripod emergency escape unit Entrapment hazard Lifelines Thermal hazard Lighting (explosive proof/low voltage) Slip or fall hazard PPE- goggles, gloves, clothing, etc. Fire Extinguisher Communication Procedures: DO NOT ENTER IF PERMISSABLE ENTRY Test Start and Stop Time: LEVELS ARE EXCEEDED Start Stop Permissable Entry Level % of Oxygen 19.5 % to 23.5 % % of LEL Less than 10% Carbon Monoxide 35 PPM (8 hr.) Hydrogen Sulfide 10 PPM (8 hr.) -

The “Best” Way to Breath

Journal of Lung, Pulmonary & Respiratory Research Case Report Open Access The “Best” way to breath Abstract Volume 2 Issue 2 - 2015 A “best” way to breath is described resulting from discovering a pre-Heimlich method Samuel A Nigro of preventing choking. Because of four episodes in three months of terrifying complete laryngospasm, the physician-patient-writer, consistent with many medical discoveries Retired, Assistant Clinical Professor Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, USA in history, discovered a method of aborting the episodes. Breathing has always been taken for granted as spontaneously and naturally most efficient. To the contrary, Correspondence: Samuel A Nigro, Retired, Assistant Clinical nasal breathing is best with first closing the mouth which enhances oxygenation and Professor Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School trans-laryngeal respiration. Physiologic aspects are reviewed including nasal and oral of Medicine, 2517 Guilford Road, Cleveland Heights, Ohio respiratory distinctions, laryngeal musculature and structures, diaphragm control and 44118, USA, Tel (216) 932-0575, Email [email protected] neuro-functional speculations. Proposed is the SAM: Shut your mouth, Air in nose, and then Mouth cough (or exhale). Benefits include prevention of choking making the Received: January 07, 2015 | Published: January 26, 2015 Heimlich unnecessary; more efficient clearing of the throat and coughs; improving oxygenation at molecular level of likely benefit for pre-cardiac or pre-stroke anoxic crises; improving exertion endurance; and offering a psycho physiologic method for emotional crises as panics, rages, and obsessive-compulsive impulses. This is a simple universal public health technique needing universal promulgation for the integration of care for all work forces and everyone else. -

Dive Medicine Aide-Memoire Lt(N) K Brett Reviewed by Lcol a Grodecki Diving Physics Physics

Dive Medicine Aide-Memoire Lt(N) K Brett Reviewed by LCol A Grodecki Diving Physics Physics • Air ~78% N2, ~21% O2, ~0.03% CO2 Atmospheric pressure Atmospheric Pressure Absolute Pressure Hydrostatic/ gauge Pressure Hydrostatic/ Gauge Pressure Conversions • Hydrostatic/ gauge pressure (P) = • 1 bar = 101 KPa = 0.987 atm = ~1 atm for every 10 msw/33fsw ~14.5 psi • Modification needed if diving at • 10 msw = 1 bar = 0.987 atm altitude • 33.07 fsw = 1 atm = 1.013 bar • Atmospheric P (1 atm at 0msw) • Absolute P (ata)= gauge P +1 atm • Absolute P = gauge P + • °F = (9/5 x °C) +32 atmospheric P • °C= 5/9 (°F – 32) • Water virtually incompressible – density remains ~same regardless • °R (rankine) = °F + 460 **absolute depth/pressure • K (Kelvin) = °C + 273 **absolute • Density salt water 1027 kg/m3 • Density fresh water 1000kg/m3 • Calculate depth from gauge pressure you divide press by 0.1027 (salt water) or 0.10000 (fresh water) Laws & Principles • All calculations require absolute units • Henry’s Law: (K, °R, ATA) • The amount of gas that will dissolve in a liquid is almost directly proportional to • Charles’ Law V1/T1 = V2/T2 the partial press of that gas, & inversely proportional to absolute temp • Guy-Lussac’s Law P1/T1 = P2/T2 • Partial Pressure (pp) – pressure • Boyle’s Law P1V1= P2V2 contributed by a single gas in a mix • General Gas Law (P1V1)/ T1 = (P2V2)/ T2 • To determine the partial pressure of a gas at any depth, we multiply the press (ata) • Archimedes' Principle x %of that gas Henry’s Law • Any object immersed in liquid is buoyed -

EPA COVID-19 Job Hazard Analysis (JHA) Supplement, July 6, 2020, Final

EPA COVID-19 Job Hazard Analysis (JHA) Supplement, July 6, 2020, Final Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. OSHA Worker Exposure Risk to COVID-19, Summary 3. Pre-Travel Considerations 4. EPA COVID-19 Job Hazard Analysis (JHA) Supplement Instructions 5. EPA COVID-19 Job Hazard Analysis (JHA) Supplement Template 6. EPA COVID-19 OLEM Job Hazard Analysis Supplement Example 1. Introduction • The COVID-19 Public Health Emergency is very dynamic. Federal, state and local government guidance is updated frequently. There may be new CDC, OSHA or EPA guidance that will impact the current content of this JHA prior to the next update. As a result, it is important to review the government links in this JHA for new information. Additionally, due to possible differences in state or local health department requirements on COVID-19, the employee, supervisor and the SHEMP manager should review applicable state/local requirements before traveling and deployment to a site. These state/local requirements may be more flexible for essential workers that are traveling into the area, and EPA travel for field work may qualify as such essential travel. • Prior to travel, assess the prevalence for COVID-19 cases in the area(s) you are traveling to (and through) in addition to where you will be performing site work. This assessment should include evaluation of whether the area has demonstrated a downward trajectory of positive tests and documented cases within a 14-day period. Including this will help staff determine how to “assess the prevalence.”. • Specific COVID-19 information can be found on state/territorial/local government and health department websites. -

Near Drowning

Near Drowning McHenry Western Lake County EMS Definition • Near drowning means the person almost died from not being able to breathe under water. Near Drownings • Defined as: Survival of Victim for more than 24* following submission in a fluid medium. • Leading cause of death in children 1-4 years of age. • Second leading cause of death in children 1-14 years of age. • 85 % are caused from falls into pools or natural bodies of water. • Male/Female ratio is 4-1 Near Drowning • Submersion injury occurs when a person is submerged in water, attempts to breathe, and either aspirates water (wet) or has laryngospasm (dry). Response • If a person has been rescued from a near drowning situation, quick first aid and medical attention are extremely important. Statistics • 6,000 to 8,000 people drown each year. Most of them are within a short distance of shore. • A person who is drowning can not shout for help. • Watch for uneven swimming motions that indicate swimmer is getting tired Statistics • Children can drown in only a few inches of water. • Suspect an accident if you see someone fully clothed • If the person is a cold water drowning, you may be able to revive them. Near Drowning Risk Factor by Age 600 500 400 300 Male Female 200 100 0 0-4 yr 5-9 yr 10-14 yr 15-19 Ref: Paul A. Checchia, MD - Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital Near Drowning • “Tragically 90% of all fatal submersion incidents occur within ten yards of safety.” Robinson, Ped Emer Care; 1987 Causes • Leaving small children unattended around bath tubs and pools • Drinking -

Cough and Laryngospasm Prevention During Orotracheal Extubation In

Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology 71 (2021) 90---95 LETTER TO THE EDITOR −1 −1 0.25 mg.kg and ketamine 0.25 mg.kg also have showed Cough and laryngospasm 4 being effective for such purpose. prevention during orotracheal The timing of extubation according to the child’s breath- extubation in children with ing cycle is another point of interest. The author of an SARS-CoV-2 infection educational review about extubation in children mentions that he extubates the child at the end of spontaneous inspi- Dear Editor, ration without suction or positive pressure, arguing that at this point the child’s lungs are full of O2-enriched air and that Little is mentioned about the importance of avoiding cough the first trans laryngeal movement of air that follows directs and laryngospasm during extubation in the Operating Room all secretions away from the laryngeal structures decreasing 5 (OR) in pediatric patients with suspected or confirmed SARS- the risk of laryngospasm. CoV-2 infection. Coughing is an important source of viral According to the former, from the perspective of respira- contagion among humans and must be considered a high-risk tory complications associated with extubation, it is safer for complication for the health workers. Laryngospasm, more the health personnel to perform the extubation to a deep frequent in children than in adults, compels to intervene anesthetized patient, during spontaneous ventilation at the with positive pressure on the patient’s airway increasing the end of inspiration and in lateral decubitus. Special attention described risk. Different from intubation in the OR, where must be given to the use of the medications described for the anesthesiologist has certain control on the procedure, coughing and laryngospasm prevention after the withdrawal extubation and emergence from anesthesia have a greater of the orotracheal tube.