An Attempt to Discriminate the Styles of English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

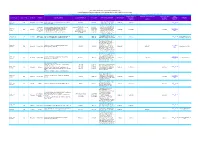

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits Made Under S31(6) Highways Act 1980

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits made under s31(6) Highways Act 1980 and s15A(1) Commons Act 2006 For all enquiries about the contents of the Register please contact the: Public Rights of Way and Highway Records Manager email address: [email protected] Telephone No. 0345 603 7631 Highway Highway Commons Declaration Link to Unique Ref OS GRID Statement Statement Deeds Reg No. DISTRICT PARISH LAND DESCRIPTION POST CODES DEPOSITOR/LANDOWNER DEPOSIT DATE Expiry Date SUBMITTED REMARKS No. REFERENCES Deposit Date Deposit Date DEPOSIT (PART B) (PART D) (PART C) >Land to the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops Christopher James Harold Philpot of Stortford TL566209, C/PW To be CM22 6QA, CM22 Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton CA16 Form & 1252 Uttlesford Takeley >Land on the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops TL564205, 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. 6TG, CM22 6ST Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM1 4LN Plan Stortford TL567205 on behalf of Takeley Farming LLP >Land on east side of Station Road, Takeley, Bishops Stortford >Land at Newland Fann, Roxwell, Chelmsford >Boyton Hall Fa1m, Roxwell, CM1 4LN >Mashbury Church, Mashbury TL647127, >Part ofChignal Hall and Brittons Farm, Chignal St James, TL642122, Chelmsford TL640115, >Part of Boyton Hall Faim and Newland Hall Fann, Roxwell TL638110, >Leys House, Boyton Cross, Roxwell, Chelmsford, CM I 4LP TL633100, Christopher James Harold Philpot of >4 Hill Farm Cottages, Bishops Stortford Road, Roxwell, CMI 4LJ TL626098, Roxwell, Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton C/PW To be >10 to 12 (inclusive) Boyton Hall Lane, Roxwell, CM1 4LW TL647107, CM1 4LN, CM1 4LP, CA16 Form & 1251 Chelmsford Mashbury, Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM14 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. -

Media Pack WATP

Waltham Abbey Press and media information Produced by Waltham Abbey Town Partnership (WATP) www.watp.org.uk 1 Table of Contents Why be based at Waltham Abbey, the tranquil Market Town set in the Lea Valley?----------------------------------------4 What's so special about Waltham Abbey?-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------4 Waltham Abbey Gateway to England--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------5 Local people to interview-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 Experience Waltham Abbey----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 Waltham Abbey History through the ages---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------7 Indoor locations for filming and interviewing----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------12 Indoor locations for filming and interviewing----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------13 Outdoor locations for filming and -

Ricardian Bulletin Edited by Elizabeth Nokes and Printed by St Edmundsbury Press

Ricardian Bulletin Magazine of the Richard III Society ISSN 0308 4337 Winter 2003 Richard III Society Founded 1924 In the belief that many features of the traditional accounts of the character and career of Richard III are neither supported by sufficient evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society aims to promote in every possible way research into the life and times of Richard III, and to secure a re-assessment of the material relating to this period and of the role in English history of this monarch Patron HRH The Duke of Gloucester KG, GCVO Vice Presidents Isolde Wigram, Carolyn Hammond, Peter Hammond, John Audsley, Morris McGee Executive Committee John Ashdown-Hill, Bill Featherstone, Wendy Moorhen, Elizabeth Nokes, John Saunders, Phil Stone, Anne Sutton, Jane Trump, Neil Trump, Rosemary Waxman, Geoffrey Wheeler, Lesley Wynne-Davies Contacts Chairman & Fotheringhay Co-ordinator: Phil Stone Research Events Adminstrator: Jacqui Emerson 8 Mansel Drive, Borstal, Rochester, Kent ME1 3HX 5 Ripon Drive, Wistaston, Crewe, Cheshire CW2 6SJ 01634 817152; e-mail: [email protected] Editor of the Ricardian: Anne Sutton Ricardian & Bulletin Back Issues: Pat Ruffle 44 Guildhall Street, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk IP33 1QF 11 De Lucy Avenue, Alresford, Hants SO24 9EU e-mail: [email protected] Editor of Bulletin Articles: Peter Hammond Sales Department: Time Travellers Ltd. 3 Campden Terrace, Linden Gardens, London W4 2EP PO Box 7253, Tamworth, Staffs B79 9BF e-mail: [email protected] 01455 212272; email: [email protected] Librarian -

1 Thrift Cottage, Sewardstone Road, Waltham Abbey, Essex, EN9

Thrift Cottage, Sewardstone Road, Waltham Abbey, Essex, EN9 1NP ARCHITECTS INTERIOR DESIGNERS PARTY WALL SURVEYORS TOWN PLANNING CONSULTANTS Hertfordshire Oce 25 Tudor Hall Brewery Road Hoddesdon Her tfordshire EN11 8NZ THRIFT COTTAGE, Sewardstone Road, Waltham Abbey, Essex, EN9 1NP t: 01992 469001 f: 01992 469002 Heritage Statement and Heritage Impact Assessment to accompany submission of application forms and drawings for Listed Building consent for the demolition of London Oce 9 Devonshire Square the property London EC2M 4YF t: 0207 9792026 f: 01992 469002 e: [email protected] w: www.dpa-architects.co.uk 1 View of Thrift Hall and Thrift Cottage looking north-east across Sewardstone Road (April 2015) 2 Thrift Cottage, Sewardstone Road, Waltham Abbey, Essex, EN9 1NP 3 CONTENTS: 1. Preambles 2. Description of the building, summarising its location, condition and the proposal to demolish with an outline of reasons why; 3. Statement of the Values and Significance of the Building (including a brief discussion and critique of why it was included in the Listed Buildings Register); 4. Statement of the setting of the building and of the impacts on this setting of recent developments; 5. A review of National Planning Policy Framework, associated Planning guidance and Local Plan policies to put the proposal into context; 6. Option Appraisal for the Conservation of this listed building; 7. Summary and Conclusions: Justification for the proposed demolition, including structural condition, conservation deficit and lack of market attractiveness; Appendix 1: Listed Building Description (1974), revision (2010) with recommendation not to de-list; Appendix 2 : Evidence base : (1) Historic map regression analysis (2) Sources of Information, reference et.c. -

(The Commons Registration Authority) Index

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits made under s31(6) Highways Act 1980 and s15A(1) Commons Act 2006 For all enquiries about the contents of the Register please contact the: Public Rights of Way and Highway Records Manager email address: [email protected] Telephone No. 0345 603 7631 Highway Statement Highway Declaration Expiry Date Commons Statement Link to Deeds Reg No. Unique Ref No. DISTRICT PARISH LAND DESCRIPTION OS GRID REFERENCES POST CODES DEPOSITOR/LANDOWNER DEPOSIT DATE Deposit Date Deposit Date SUBMITTED REMARKS (PART B) (PART C) (PART D) DEPOSIT Gerald Paul George of The Hall, C/PW To be All of the land being The Hall, Langley Upper Green, Saffron CA16 Form & 1299 Uttlesford Saffron Walden TL438351 CB11 4RZ Langley Upper Green, Saffron 23/07/2021 23/07/2021 allocated. Walden, CB11 4RZ Plan Walden, Essex, CB11 4RZ Ms Louise Humphreys, Webbs Farmhouse, Pole Lane, White a) TL817381 a) Land near Sudbury Road, Gestingthorpe CO9 3BH a) CO9 3BH Notley, Witham, Essex, CM8 1RD; Gestingthorpe, b) TL765197, TL769193, TL768187, b) Land at Witham Road, Black Notley, CM8 1RD b) CM8 1RD Ms Alison Lucas, Russells Farm, C/PW To be Black Notley, TL764189 CA16 Form & 1298 Braintree c) Land at Bulford Mill Lane, Cressing, CM77 8NS c) CM77 8NS Braintree Road, Wethersfield, 15/07/2021 15/07/2021 15/07/2021 allocated. Cressing, White c) TL775198, TL781198 Plan d) Land at Braintree Road, Cressing CM77 8JE d) CM77 8JE Braintree, Essex, CM7 4BX; Ms Notley d) TL785206, TL789207 e) Land -

Greenwood House, Church Street, Waltham Abbey, EN9 1DX Offers in Region of £280,000 • GATED PARKING to REAR

• LUXURY TOWN CENTRE DEVELOPMENT Greenwood House, Church Street, Waltham Abbey, EN9 1DX Offers In Region Of £280,000 • GATED PARKING TO REAR • RESIDENT GYM JOIN US FOR A GLASS OF FIZZ ON OUR OPEN DAY - MONDAY 27TH MAY - Call for your personal time slot. EXCITING * HIGH SPEC* LUXURY TOWN CENTRE DEVELOPMENT * READY TO OCCUPY* RESIDENTS GYM* Stunning finishes throughout, quality • HIGH SPEC FINISH THROUGHOUT fitments, gated parking. ABBEY CHURCH VIEWS Property Description OVER-VIEW THREE high specification - two bedrooms flats in this stunning town centre development. The development affords stunning views to the front aspect over the grounds of the impressive Waltham Abbey Church of Waltham Holy Cross and St Lawrence. The setting is both unique and unrivalled being opposite the historic grounds dating back to the 10th Century. There is a charming history for Waltham Abbey Gardens citing guests as renowned as Henry IIIV and Anne Boleyn alongside King Harold who is said to have been buried here in 1066. To be able to benefit from acres of protected parkland and live in the heart of this charming market town is an opportunity to be embraced and will appeal to those looking for a distinctive and inspiring lifestyle. The flats vary in location within the development and each flat has a unique selling point depending on your personal requirements. Prices from £280,000 to £290,000 for the two bedroom apartments. 25 Market Square, Waltham Abbey, Agents Note: Whilst every care has been taken to prepare these particulars, they are for guidance purposes only. All measurements are approximate are for general www.rainbowestateagents.co.uk guidance purposes only and whilst every care has been taken to ensure their accuracy, they should not be relied upon and potential buyers/tenants are advised to Essex, EN9 1DU 01992 711222 recheck the measurements [email protected]. -

The Friends of Waltham Abbey Church Registered Charity

The Friends of Waltham Abbey Church Registered Charity. No: 1044663 The Friends of Waltham Abbey Church was set up during the 1960s restoration of the Church. The aim of the Friends group is to help raise funds for the upkeep, maintenance and enhancement of the Church fabric. The funds are mainly raised from Visitor Centre sales and Membership fees. Join today and help boost our funds The annual membership fee is a minimum of £5.00 We have Members from all over the UK and abroad. Members are sent a newsletter, are invited to an annual Friends’ Evensong as well as an annual social outing to a place of interest. The Visitor Centre is manned entirely by volunteers, and has many items including bibles, books, church guides, wrapping paper and cards of various kinds. If you are interested in becoming a volunteer then please call in at the Visitor Centre. Membership forms are also available online. APPLICATION FOR MEMBERSHIP OF THE FRIENDS OF WALTHAM ABBEY CHURCH I would like to become a member of The Friends of Waltham Abbey Church Full Name……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Full address………………………………………………………………………………………………..................................................... …………………………………………………………Postcode…………………….. Signature……………………………………………………. I enclose………………………………….. pounds (£ ) as my first annual subscription OR I have completed the Bankers Order Form UK taxpayers are invited to fill out the Gift Aid form to enable the tax on the donation to be reclaimed. Return your completed forms to the Visitor Centre in the Church or to the Parish Office, Abbey Church Centre, Abbey Farmhouse, Abbey Gardens, Waltham Abbey, Essex EN9 1XQ marked for the attention of The Friends of Waltham Abbey Church Membership Secretary. -

The Chronology of Medival and Renaissance Architecture

Dear Reader, This book was referenced in one of the 185 issues of 'The Builder' Magazine which was published between January 1915 and May 1930. To celebrate the centennial of this publication, the Pictoumasons website presents a complete set of indexed issues of the magazine. As far as the editor was able to, books which were suggested to the reader have been searched for on the internet and included in 'The Builder' library.' This is a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by one of several organizations as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. Wherever possible, the source and original scanner identification has been retained. Only blank pages have been removed and this header- page added. The original book has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books belong to the public and 'pictoumasons' makes no claim of ownership to any of the books in this library; we are merely their custodians. Often, marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in these files – a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Since you are reading this book now, you can probably also keep a copy of it on your computer, so we ask you to Keep it legal. -

The Major New BBC1 Series – 'How We Built Britain' Looks at the History of the Country Through Our Buildings

How we Built Britain The BBC1 series – ‘How we Built Britain’ (shown Summer 2007) looked at the history of the country through our buildings. The first programme featured the East of England region – which abounds in outstanding examples of architecture. From Britain’s greatest collection of cathedrals to the award-winning terminal at Stansted Airport. Discover flint and timber buildings, and stately homes dating from Tudor to Victorian times. Over the next few pages we have listed a selection of key places to visit - check out our web site at www.visiteastofengland.com for opening times and admission prices. Architecture of the Region Building stone is virtually non-existent in the East of England, apart from a few special areas: z Barnack (Cambridgeshire) - the famous limestone here was worked from Roman times to the end of the 15th C. Ely and Peterborough Cathedrals are good examples of the stone in use. z Carstone (West Norfolk) - this dark brown stone forms a ridge between Castle Rising and Heacham. It has been widely used in the area as a building stone, and Downham Market was once known as the "Gingerbread town". z Puddingstone (Hertfordshire) - this unusual stone is made up of rounded Flint villages flint pebbles. A large piece sits opposite the church in the village of Standon. It has been used for building walls. z Sandstone - The Greensand Ridge runs from Leighton Buzzard in Bedfordshire to Gamlingay in Cambridgeshire. In some places, ‘glauconite’ (an iron-bearing mineral) colours the stone an amazing green - the origin of the name ‘Greensand’. Today you can see it used in local villages, churches, walls and bridges. -

Full 1497.Pdf

No 19 HISTORIC CHURCHES a wasting asset Warwick Rodwell with Kirsty Rodwell 1977 Historic churches— a wasting asset Warwick Rodwell with Kirsty Rodwell 1977 Research Report No 19 The Council for British Archaeology 1 © W J Rodwell 1977 Published by the Council for British Archaeology, 7 Marylebone Road, London NW1 5HA Designed by Allan Cooper FSIA and Henry Cleere The CBA wishes to acknowledge the grant from the Department of the Environment towards the publication of this report. Printed at Tomes of Leamington. ii Contents Introduction v Section 1 Explanation of the Survey Background to the Survey Definition and scope of church archaeology 1 Summary of findings and recommendations 3 Section 2 Content of the Survey The Diocesan background 4 Scope and limitations 4 Methods of approach 4 The grading of churches 5 Section 3 The Present State of Churches in the Diocese Living churches, built before 1750 9 Living churches, rebuilt after 1750 10 Churches made redundant since 1952 11 Ruined and demolished churches 13 Churches of reduced size 17 Section 4 The History of Church Archaeology in the Chelmsford Diocese Church excavations 19 Section 5 Case Study 1—Churches in an Historic Town The ancient churches of Colchester 24 Parochial churches 24 Non-parochial churches 37 Conclusions 39 Section 6 Case Study 2—A Rural Parish Church St Mary and All Saints’ Church, Rivenhall 42 Section 7 Case Study 3—An Anglo-Saxon Minster St Botolph’s Church, Hadstock 50 Section 8—Case Study 4—Church Conversions St Lawrence’s Church, Asheldham 55 St Michael’s Church, -

Waltham Abbey Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan

Waltham Abbey Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan March 2016 Waltham Abbey Conservation Area Character Appraisal March 2016 Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................... 4 1.1 Definition and purpose of conservation areas ...................................... 4 1.2 Purpose and scope of character appraisals ......................................... 4 1.3 Extent of Waltham Abbey Conservation Area .................................... 4 1.4 Methodology ........................................................................................ 4 2. Planning Policy Context ....................................................................... 5 2.1 National Policy and Guidance .............................................................. 5 2.2 Historic England Guidance .................................................................. 5 2.3 Local Plan Policies............................................................................... 5 3. Summary of Special Interest ................................................................ 6 3.1 Definition of special architectural and historic interest ......................... 6 3.2 Definition of the character of Waltham Abbey Conservation Area ....... 6 4. Location and Population ...................................................................... 6 5. Topography and Setting ....................................................................... 7 6. Historical Development and Archaeology ......................................... -

The Seven Periods of English Architecture, by 1

The Seven Periods of English Architecture, by 1 The Seven Periods of English Architecture, by Edmund Sharpe This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Seven Periods of English Architecture Defined and Illustrated Author: Edmund Sharpe Illustrator: T. Austin Release Date: February 14, 2012 [EBook #38879] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SEVEN PERIODS OF ENGLISH *** Produced by Chris Curnow, Diane Monico, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive) THE The Seven Periods of English Architecture, by 2 SEVEN PERIODS OF ENGLISH ARCHITECTURE. THE SEVEN PERIODS OF ENGLISH ARCHITECTURE DEFINED AND ILLUSTRATED. BY EDMUND SHARPE, M.A., ARCHITECT. TWENTY STEEL ENGRAVINGS AND WOODCUTS. THIRD EDITION. [Illustration] E. & F. N. SPON, 125, STRAND, LONDON. NEW YORK: 12, CORTLANDT STREET. 1888. PREFACE. "We have been so long accustomed to speak of our National Architecture in the terms, and according to the classification bequeathed to us by Mr. Rickman, and those terms and that classification are so well understood and have been so universally adopted, that any proposal to supersede the one, or to modify the other, requires somewhat more than a mere apology. To disturb a Nomenclature of long standing, to set aside terms in familiar use, and to set up others in their place which are strange, and therefore at first unintelligible, involves an interruption of that facility with which we are accustomed to communicate with one another on any given subject, that is only to be justified by reasons of a cogent and satisfactory nature.