Full 1497.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Environment Characterisation Project

HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT Chelmsford Borough Historic Environment Characterisation Project abc Front Cover: Aerial View of the historic settlement of Pleshey ii Contents FIGURES...................................................................................................................................................................... X ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................................................XII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................................... XIII 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT ............................................................................................................................ 2 2 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF CHELMSFORD DISTRICT .................................................................................. 4 2.1 PALAEOLITHIC THROUGH TO THE MESOLITHIC PERIOD ............................................................................... 4 2.2 NEOLITHIC................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 BRONZE AGE ............................................................................................................................................... 5 -

St. James the Less and St. Helen

May God bless you all. Fr Tony McKentey ST. JAMES THE LESS AND Please see Mass Schedule for ANY changes ST. HELEN SUNDAYS: Divine Mercy followed by Rosary 3pm CATHOLIC CHURCH, COLCHESTER DAILY: Morning Prayer 8:15am; Rosary/Divine Mercy 8:35am EVENING PRAYER: Fridays at 6pm Church WITH MERSEA, MILE END AND MONKWICK PRAYER GROUP: Mondays at 7:45pm Crypt MEDITATION GROUP: Tuesdays at 8pm Crypt Fr Anthony McKentey PRAYERS FOR THE SICK (new entries are in bold type): Please remember in your prayers; Władysław Anto ńczak, Pat Banks, June Bickersteth, Gr ace Blanchette, Fr Neil Brett Frank Campbell, Karl Collins, Olive Crawford, Jeanette Dagwell, Lynne-Michelle Fr Philip Willenbrock Denton, Joan Donnelly , Nancy Drummond, Fr Paul Dynan, Charlie George , Bill 51 Priory Street , Colchester, Essex, CO1 2QB Graves, Bert Hewitt, Norah Hewitt, Maurice Highfield, David Hill, Theresa Hogan, Tel: 01206 866317 Ronald Jay, Pat Keene, Patrick King, Declan Knight, Mirella Leonardi, Marie Lyons, Pat Maloney, Jean Mansell, Mary-Ann Martin, Cara Maude , , Byron Miller , Margaret E-Mail [email protected] Norman, Anne Renwick, Leah Patterson, Elaine Proudfoot, Ronald Quijano, S abina www.stjamesthelessandsthelen.org Rhatigan, Catherine Spicer, Arthur Urquhart, Filomena Velasquez, Patricia Wiltshire, Tony White, Dorcey Young. TWENTY-SECOND SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME [A] BAPTISMS THIS WEEKEND: This weekend we welcome into the church through st 31 August 2014 - Parish Mass Book Page 122 the Sacrament of Baptism: Matilda Kellegher, Chibueze Okechukwu, Oscar Sayles . God bless these children and congratulations to their families. My dear friends WOULD YOU LIKE TO HAVE YOUR CHILD BAPTISED? The next Baptism course Welcome on this last weekend of August. -

© Georgina Green ~ Epping Forest Though the Ages

© Georgina Green ~ Epping Forest though the Ages Epping Forest Preface On 6th May 1882 Queen Victoria visited High Beach where she declared through the Ages "it gives me the greatest satisfaction to dedicate this beautiful Forest to the use and enjoyment of my people for all time" . This royal visit was greeted with great enthusiasm by the thousands of people who came to see their by Queen when she passed by, as their forefathers had done for other sovereigns down through the ages . Georgina Green My purpose in writing this little book is to tell how the ordinary people have used Epping Fo rest in the past, but came to enjoy it only in more recent times. I hope to give the reader a glimpse of what life was like for those who have lived here throughout the ages and how, by using the Forest, they have physically changed it over the centuries. The Romans, Saxons and Normans have each played their part, while the Forest we know today is one of the few surviving examples of Medieval woodland management. The Tudor monarchs and their courtiers frequently visited the Forest, wh ile in the 18th century the grandeur of Wanstead House attracted sight-seers from far and wide. The common people, meanwhile, were mostly poor farm labourers who were glad of the free produce they could obtain from the Forest. None of the Forest ponds are natural . some of them having been made accidentally when sand and gravel were extracted . while others were made by Man for a variety of reasons. -

Pick of the Churches

Pick of the Churches The East of England is famous for its superb collection of churches. They are one of the nation's great treasures. Introduction There are hundreds of churches in the region. Every village has one, some villages have two, and sometimes a lonely church in a field is the only indication that a village existed there at all. Many of these churches have foundations going right back to the dawn of Christianity, during the four centuries of Roman occupation from AD43. Each would claim to be the best - and indeed, all have one or many splendid and redeeming features, from ornate gilt encrusted screens to an ancient font. The history of England is accurately reflected in our churches - if only as a tantalising glimpse of the really creative years between the 1100's to the 1400's. From these years, come the four great features which are particularly associated with the region. - Round Towers - unique and distinctive, they evolved in the 11th C. due to the lack and supply of large local building stone. - Hammerbeam Roofs - wide, brave and ornate, and sometimes strewn with angels. Just lay on the floor and look up! - Flint Flushwork - beautiful patterns made by splitting flints to expose a hard, shiny surface, and then setting them in the wall. Often it is used to decorate towers, porches and parapets. - Seven Sacrament Fonts - ancient and splendid, with each panel illustrating in turn Baptism, Confirmation, Mass, Penance, Extreme Unction, Ordination and Matrimony. Bedfordshire Ampthill - tomb of Richard Nicholls (first governor of Long Island USA), including cannonball which killed him. -

Essex Boys and Girls Clubs 2013 Online News Archive Our Autumn Of

Essex Boys and Girls Clubs Essex Boys and Girls Clubs. County Office, Harway House, Rectory Lane, Chelmsford CM1 1RQ Tel: 01245 264783 | Charity Number: 301447 2013 Online News Archive The following news articles were posted on the Essex Boys and Girls Clubs website in 2013. OCT-DEC 2013 National Citizen Service Autumn 2013 Our Autumn of National Citizen Service (NCS) We had another brilliant half-term delivering the government’s NCS program for 16-17 year olds. Each young person joined a cohort for a half-term of fun, adventure, training and volunteering, making new friends alongside their new experiences. They also gave an enormous amount back to their communities by planning and completing a range of social action projects. Here are the teams... Cohort 1 cleared the grounds at Frenford Clubs to help make its better environment for young people and the community. They also organised bake sales and an own-clothes days in their schools and colleges to raise £115 for Richard House Children's Hospice. Cohort 2 volunteered with Southend Round Table to run their Annual Charity Fireworks. Cohort 3 organised a Race Night and Raffle Fundraiser to raise £700 for Smiles with Grace. Cohort 4 helped out at a trampoline competition for the Recoil Twisters. They also ran a fundraising quiz night and handed out flyers to promote the work of Recoil Twisters at Brentwood Christmas Lights switch on. Cohort 5 cleared the grounds at Frenford Clubs to help make its better environment for young people and the community. They also volunteered at the National Cross-Country Championships. -

The Moral Basis of Family Relationships in the Plays of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries: a Study in Renaissance Ideas

The Moral Basis of Family Relationships in the plays of Shakespeare and his Contemporaries: a Study in Renaissance Ideas. A submission for the degree of doctor of philosophy by Stephen David Collins. The Department of History of The University of York. June, 2016. ABSTRACT. Families transact their relationships in a number of ways. Alongside and in tension with the emotional and practical dealings of family life are factors of an essentially moral nature such as loyalty, gratitude, obedience, and altruism. Morality depends on ideas about how one should behave, so that, for example, deciding whether or not to save a brother's life by going to bed with his judge involves an ethical accountancy drawing on ideas of right and wrong. It is such ideas that are the focus of this study. It seeks to recover some of ethical assumptions which were in circulation in early modern England and which inform the plays of the period. A number of plays which dramatise family relationships are analysed from the imagined perspectives of original audiences whose intellectual and moral worlds are explored through specific dramatic situations. Plays are discussed as far as possible in terms of their language and plots, rather than of character, and the study is eclectic in its use of sources, though drawing largely on the extensive didactic and polemical writing on the family surviving from the period. Three aspects of family relationships are discussed: first, the shifting one between parents and children, second, that between siblings, and, third, one version of marriage, that of the remarriage of the bereaved. -

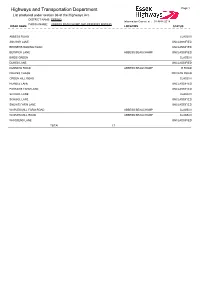

Highways and Transportation Department Page 1 List Produced Under Section 36 of the Highways Act

Highways and Transportation Department Page 1 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: EPPING Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: ABBESS BEAUCHAMP AND BERNERS RODING ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS ABBESS ROAD CLASS III ANCHOR LANE UNCLASSIFIED BERNERS RODING ROAD UNCLASSIFIED BERWICK LANE ABBESS BEAUCHAMP UNCLASSIFIED BIRDS GREEN CLASS III DUKES LANE UNCLASSIFIED DUNMOW ROAD ABBESS BEAUCHAMP B ROAD FRAYES CHASE PRIVATE ROAD GREEN HILL ROAD CLASS III HURDLE LANE UNCLASSIFIED PARKERS FARM LANE UNCLASSIFIED SCHOOL LANE CLASS III SCHOOL LANE UNCLASSIFIED SNOWS FARM LANE UNCLASSIFIED WAPLES MILL FARM ROAD ABBESS BEAUCHAMP CLASS III WAPLES MILL ROAD ABBESS BEAUCHAMP CLASS III WOODEND LANE UNCLASSIFIED TOTAL 17 Highways and Transportation Department Page 2 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: EPPING Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: BOBBINGWORTH ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS ASHLYNS LANE UNCLASSIFIED BLAKE HALL ROAD CLASS III BOBBINGWORTH MILL BOBBINGWORTH UNCLASSIFIED BRIDGE ROAD CLASS III EPPING ROAD A ROAD GAINSTHORPE ROAD UNCLASSIFIED HOBBANS FARM ROAD BOBBINGWORTH UNCLASSIFIED LOWER BOBBINGWORTH GREEN UNCLASSIFIED MORETON BRIDGE CLASS III MORETON ROAD CLASS III MORETON ROAD UNCLASSIFIED NEWHOUSE LANE UNCLASSIFIED PEDLARS END UNCLASSIFIED PENSON'S LANE UNCLASSIFIED STONY LANE UNCLASSIFIED TOTAL 15 Highways and Transportation Department Page 3 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: EPPING Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: -

Settlement Hierarchy Technical Paper September 2015

EB1007 Settlement Hierarchy Technical Paper September 2015 Settlement Hierarchy Technical Paper September 2015 1 EB1007 Settlement Hierarchy Technical Paper September 2015 Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 National Planning Policy Framework .................................................................................................. 4 Purpose of this Technical Paper .......................................................................................................... 5 2. Methodology .................................................................................................................................. 6 3. Analysis .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Adopted Policy Approach ................................................................................................................... 7 Approach of Neighbouring Authorities ............................................................................................... 7 Sustainability Appraisal (SA) Process .................................................................................................. 8 Accessibility Analysis ........................................................................................................................... 8 Town Centres Study ........................................................................................................................... -

Borley Marriages 1709-1850 (Brides)

Borley marriages 1709-1850 (brides) Bride surname Bride 1st Status Groom 1st Groom surname Status Marriage date Notes Record in different writing,entered much later? Suspect it is somebody's jotting. Similar record from Stoke by Nayland ? Elener Joseph ENGLISH * * 1696 looks more likely. ADAMS Susanna William BRACKITT 01 Oct 1732 Groom abode: Sudbury, bride abode: Glemsford ALLARD Elisabeth Henry AMBROSE 28 Jun 1733 Banns. He used mark, she signed. Witnesses: English Hart, ALLEN Elizabeth Spinster John CHINERY Bachelor 01 Jan 1793 Henry & Ann Chinery ARGENT Mary Cornelius BARTON 29 Sep 1730 ARGENT Sarah Widow John BIRD Widower 31 Dec 1742 He used mark, she signed. Groom occ: labourer. Groom father: George Ward. Bride father: John Aves, labourer. Witnesses: AVES Mary Spinster Isaac WARD Bachelor 15 Jun 1847 David & Mary Ann Ward Banns. Both used mark. Witnesses: Barnard Mills, Martha BAKER Mary Joseph FROST Widower 07 May 1776 Frost, John Hart Licence. Both signed. Bride abode: Stisted. Witnesses: BAKER Rachel Spinster Joseph FIRMIN Bachelor 29 Mar 1796 Elizabeth Baker, George & Ths Firmin. Licence. Both signed. Groom abode: Patteswick. Witnesses: BAKER Susanna Spinster Richard BRIDGE Bachelor 23 Feb 1797 Joseph & Rachel Firmin Both used mark. Groom occ: labourer. Groom abode: Belchamp St Paul. Groom father: Robert Frost, labourer. Bride father: John Barber, labourer. Witnesses: William & Anne BARBER Maria Spinster James FROST Bachelor 27 Jun 1841 Barber Both used mark. Groom occ: labourer. Groom father: William Seaber. Bride father: John Barber. Witnesses: William BARBER Ann Spinster David SEABER Bachelor 06 Aug 1843 Theobald, Hariet Wadley BENSON Dinah Thomas ALLEN 27 Jun 1735 Groom abode: Great Yeldham, bride abode: Hedingham Sible BENWAIT Jane Widow Thomas WELLS Widower 02 Dec 1743 Groom abode: Sudbury, bride abode: Henny Mag. -

From: the Dean the Very Revd Nicholas Henshall

From: The Dean The Very Revd Nicholas Henshall 9 June 2020 CHELMSFORD CATHEDRAL RE-OPENING Chelmsford Cathedral is re-opening for personal prayer and reflection on 4th July and will then be open every day from 11 am to 3 pm. The Dean writes: I am delighted to announce that Chelmsford Cathedral is re-opening for personal prayer and reflection on 4th July. The Cathedral will then be open daily from 11 am to 3 pm. This is a great moment, and it is important to stress that is just a first step. Public worship will not resume for some time to come, but it has been wonderful to welcome so many joining us on-line for the daily prayer. That will continue to be streamed live on Facebook at 7.45 am and 5.15 pm every day, with the Eucharist streamed on Sundays at 10.30 am. From 4th July the interior of the Cathedral will be laid out in a different way. This is to comply fully with guidance from the Government and from the Church of England. We are determined to ensure that everyone who visits the Cathedral can do so in full confidence that it is a safe and secure environment. A one-way system will be in operation through the Cathedral, with everyone entering through the South Door and leaving through the North Door. There will be handwash at the door which everyone must use, and certain areas will not accessible, including the vestry block. Any seating in the Cathedral will be appropriately distanced, and every chair will be cleaned after every use, in accordance with the guidelines. -

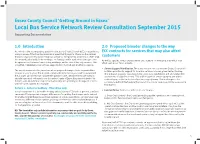

ECC Bus Consultation

Essex County Council ‘Getting Around in Essex’ Local Bus Service Network Review Consultation September 2015 Supporting Documentation 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Proposed broader changes to the way As set out in the accompanying questionnaire, Essex County Council (ECC) is undertaking ECC contracts for services that may also affect a major review of the local bus services in Essex that it pays for. These are the services that are not provided by commercial bus operators. It represents around 15% of the total customers bus network, principally in the evenings, on Sundays and in rural areas although some As well as specific service changes there are a number of other proposals which may do operate in or between towns during weekdays and as school day only services. This affect customers. These include: consultation does not cover services supported by Thurrock and Southend councils. • Service Support Prioritisation. The questionnaire sets out how the County Council will The questionnaire asks for your views about proposed changes to the supported bus in future prioritise its support for local bus services in Essex, given limited funding. network in your district. This booklet contains the information you need to understand This is based on public responses to two previous consultations and a long standing the changes and allow you to answer the questionnaire. Service entries are listed in assessment of value for money. This will be based on service category and within straight numerical order and cover the entire County of Essex (they are not divided by each category on the basis of cost per passenger journey. -

CHRISTMAS BUFFET £10 Per Person

Page 28 Leaden Reading COME AND MEET UP WITH YOUR NEIGHBOURS AT THE VILLAGE HALL FOR A Volume 1, Issue No. 35 September 2018 Brownies receive letters from CHRISTMAS the Princes Before the summer break the Brownies made a horseshoe col- lage to send to Prince Harry and Meghan Markle to celebrate BUFFET their marriage. Towards the end of term, they received a letter of thanks from the couple (see below) which they will frame and put up in the village hall for all to see alongside one of the thank you cards ALL WELCOME they individually received from the Duke and Duchess of Cam- bridge after they sent congratulation cards on the birth of Inside this Issue Prince Louis. Who’s who? 2 BAR WILL BE OPEN AND THERE WILL BE Village Hall /Music Quiz 3 MUSIC AND GAMES Village Hall/ Lottery 4 Christmas Presents for Children from Father Christmas Bowls Club 5 Cream Teas 6 Tribute to Brian Lodge 7 SUNDAY 9TH Church & Stansted Airport 8 Recycling, Fire Stat. Open Day 9 Fyfield Scouts / Citizens Advice DECEMBER FROM 2PM 10 /11 Citizens Advice 12 RWC 13 £10 per person Dog Bins/Mobile Library 14 Mutts in Distress 15 Rodings Villages 16 (£5 under 14) Rodings Brownies/Dog Show 17 Buness’s 18 Parish Council 19/23 BOOK YOUR TABLE NOW! Kemi Badenoch MP/Cloghams 24 CALL IVY 01279 876568 Roding’s Fire Service 25 What is coming up in the Village this Autumn? Summer in Leaden Roding 26/27 Leaden Roding Xmas Buffett 28 Plenty of Bowls nights.