The Islamic Monetary Standard: the Dinar and Dirham Adam Abdullah*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implementation of the Gold Dinar: Is It the End of Speculative Measures?

Journal of Economic Cooperation 23 , 3 (2002) 71-84 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE GOLD DINAR: IS IT THE END OF SPECULATIVE MEASURES? Dr. Abu Bakar Bin Mohd Yusuf * Nuradli Ridzwan Shah Bin Mohd Dali* Norhayati Mat Husin* The Asian economic crisis, which occurred in 1997, hit the Malaysian and neighbouring countries economies badly. Thailand and South Korea had to turn to IMF rehabilitation funds to ensure that they could revive their economic growth. Suprisingly, Malaysia took an unorthodox way by implementing capital control and pegging the National Ringgit Malaysia at 3.80 to the US dollar. Prime Minister Dato Seri Dr. Mahathir Mohamad blames speculators which contributed heavily to the country's depreciating currency value, thus affecting the overall national economic condition. Even though the SEA countries are feeling the pain from the crisis, their overall economic conditions are moving towards positive reactions after several economic measures have been taken by the affected countries. In the process of economic recovery, Malaysia is searching for an alternative solution to decrease the possibilities of being attacked by speculators. Prime Minister Dato Seri Dr. Mahathir Mohamad first expressed interest in a universal currency that could help unite Muslim countries after attending the OIC summit in Doha, Qatar, in November 2000. This paper will discuss whether the implementation of the universal currency, or the Gold Dinar will stop the speculators’ menace. 1. OVERALL FINANCIAL CRISIS Asia was slashed down by the international financial crisis which spread to other continents. Consequently, efforts to strengthen the architecture of the international financial system, involving finance ministries and central banks from both developed and emerging market economies, have been made. -

International Journal of Islamic Economics and Finance Studies

IJISEF INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ISLAMIC ECONOMICS AND FINANCE STUDIES Uluslararası İslam Ekonomisi ve Finansı Araştırmaları Dergisi November 2016, Kasım 2016, Vol: 2, Issue: 3 Cilt: 2, Sayı: 3 e-ISSN: 2149-8407 p-ISSN: 2149-8407 journal homepage: http://ijisef.org/ Islamic Perspective on the Impact of Ethics and Tax for Nigerian Economic Development Almustapha A. Aliyu Department of Accounting, University of Sokoto, [email protected] Mohammed Yusuf Alkali Department of Accounting, Federal Polytechnic Birnin Kebbi, [email protected] Ibrahim Alkali Ministry of Finance Birnin Kebbi, [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT The tax system, policies, and structures have been one of the significant factors that directly affect the social and economic activities of any nation. Despite the importance of tax, the attitude of the taxpayers, their reaction concerning tax, could in greater sense facilitate or draw back the policies Keywords: Ethics, Tax and system from their original intention and purposes, particularly from Evasion, Tax an Islamic perspective. Islamic tax income is for the benefits of poor, Avoidance, Nigerian needy and less privileged people in the society. Even though, policies on Economy, Economic tax approved tax avoidance and made it legal, however, tax evasion is Development illegal in all society because it will deviate from its purpose. The most significant point, however, evading taxes by the people is viewed as unethical behaviour in any economy as the consequences could be greater to the economy and society. Several countries used Islamic system of tax because of the ethics of the system and possibly fewer evasions by the Muslims. Given that, with the number of the Nigerian Muslims, adoption of Islamic tax system will improve the revenue generation, and © 2016 PESA All rights thereby enhance the economic development of Nigerian economy. -

Treasury Reporting Rates of Exchange As of March 31, 1965

iA-a 1902 (lTlslon of Central Account* and Reports ipproTed 10/63 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF MARCH 31, 1965 TREASURY DEPARTMENT FISCAL SERVICE BUREAU OF ACCOUNTS TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF MARCH 31, 1965 Prescribed pursuant to section 613 of P.L. 87-195 and section 4a(3) of Procedures Memorandum No. 1, Treasury Circular No. 930, for pur poses of reporting, with certain exceptions, foreign currency bal ances as of March 31, 1965 and transactions for the quarter ending June 30, 1965. RATES OF EXCHANGE COUNTRY F.C. TO &1.00 TYPE OF CURRENCY Aden 7.119 East African shillings Afghanistan 65.00 Afghan afghanis Algeria 4.900 Algerian dinars Argentina 149.5 Argentine pesos Australia .4468 Australian pounds Austria 25.74 Austrian schillings Azores 28.68 Portuguese escudos Bahamas .3574 Bahaman pounds Belgium 49.62 Belgian francs Bermuda .3577 Bermudian pounds Bolivia 11.88 Bolivian pesos Brazil 1825. Brazilian cruzeiros British Honduras 1.430 British Honduran dollars British West Indies 1.714 British West Indian dollars Bulgaria 2.000 Bulgarian leva Burma 4.725 Burmese kyats Cambodia 34.49 Cambodian riels Canada 1.075 Canadian dollars Ceylon 4.758 Ceylonese rupees Chile 3.410 Chilean escudos China (Taiwan) 40.00 New Taiwan dollars Colombia 13.85 Colombian pesos Congo, Republic of the 150.0 Congolese francs Costa Rica 6.620 Costa Rican colones Cyprus .3568 Cyprus pounds Czechoslovakia 14.35 Czechoslovakian korunas Dahomey 245.0 C.F.A. francs Denmark 6.911 Danish kroner Dominican Republic 1.000 Dominican Republic pesos Ecuador 18.47 Ecuadoran sucres El Salvador 2.500 Salvadoran colones Ethiopia 2.481 Ethiopian dollars Fiji Islands -3935 Fijian pounds Finland 3.203 Finnish new markkas France 4.900 French francs French West Indies 4.899 French francs Page 1 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF MARCH 31, 1965 (Continued) RATE OF EXCHANGE COUNTRY F.C. -

Perkembangan Perekonomian Ekonomi

i PERKEMBANGAN PEMIKIRAN EKONOMI ISLAM i Sanksi Pelanggaran Hak Cipta Undang-Undang Republik Makassar No. 19 Tahun 2002 tentang Hak Cipta Lingkup Hak Cipta Pasal 2: 1. Hak Cipta merupakan hak eksklusif bagi pencipta dan pemegang Hak Cipta untuk mengumumkan atau memperbanyak ciptaannya, yang timbul secara otomatis setelah suatu ciptaan dilahirkan tanpa mengutrangi pembatasan menurut peraturan perundang-undangan yang berlaku. Ketentuan Pidana Pasal 72: 1. Barang siapa dengan sengaja atau tanpa hak melakukan perbuatan sebagaimana dimaksud dalam pasal 2 ayat (1) atau pasal 49 ayat (1) dan (2) dipidana dengan pidana penjara masing-masing paling singkat 1 (satu) bulan dan/atau denda paling banyak Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (lima milyar rupiah). 2. Barang siapa dengan sengaja menyiarkan, memamerkan mengedarkan, atau menjual kepada umum suatu ciptaan atau barang hasil pelanggaran Hak Cipta atau Hak Terkait sebagaimana dimaksud dalam ayat (1) dipidana dengan pidana penjara paling lama 5 (lima) tahun dan/atau denda paling banyak Rp 500.000.000,00 (lima ratus juta rupiah). ii DR. ABDUL RAHIM S.Ag,M.Si,MA PERKEMBANGAN PEMIKIRAN EKONOMI ISLAM PENERBIT YAYASAN BARCODE 2020 iii PERKEMBANGAN PEMIKIRAN EKONOMI ISLAM Penulis: Dr. Abdul Rahim,S.Ag.,M.SI,MA Tata Letak/Desain Cover: Sulaiman Sahabuddin, S.Pd.i Editor : Juhasdi SE,MM Copyright © 2020 Perpustakaan Nasional: Katalog Dalam Terbitan (KDT) ISBN: 978-623-285-080-4 23x15 cm Diterbitkan pertama kali oleh: YAYASAN BARCODE Divisi Publikasi dan Penelitian Jl. Kesatuan 3 No. 11 Kelurahan Maccini Parang Kecamatan Makassar, Kota Makassar Email: [email protected] HP. 0813-4191-0771 iv KATA PENGANTAR Puji syukur kita panjatkan kepada Allah SWT. -

Islamic Credit Cards: How Do They Work, and Is There a Better Alternative?

Journal of Islamic Banking and Finance December 2017, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 1-8 ISSN 2374-2666 (Print) 2374-2658 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/jibf.v5n2a1 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/jibf.v5n2a1 Islamic Credit Cards: How Do They Work, And Is There A Better Alternative? Bukhari M. S. Sillah1 Abstract Credit card, which is one of the noncash payment methods, has been growing exponentially. Credit card generally uses credit balances advanced by the banks to make payments. The banks charge cardholders for using the credit payment system or based on the outstanding balances owed. Charging fees based on the outstanding balances can tantamount to Riba Nasi’ah. To avoid thisRiba, the Islamic banks have packaged their cards based on certain Islamic ‘transaction principles’. These packages include Charge cards, Qard Al-hasan cards, Bay Al-Inah cards, Tawarruq cards, and Murabahah cards.Some of these packages have become subjects of increasing juristic criticism. I review these packages and conclude that they suffer either from reduced Shari’ah compliance or high price.I propose an alternative package that could minimize the juristic criticisms and improve competitiveness. It extends the Tawarruq package by introducing a buy-and-hold element in the ownership of the underlying asset. It eliminates the need for revolving money credit that can attract interest charges and replaces it with cash reserve and asset holding that the cardholder replenishes as he/she makes repayments into his/her card. 1. Introduction Credit card, which is one of the noncash payment methods, has been growing exponentially. -

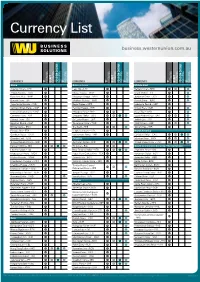

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Riba, Interest and Six Hadiths

Riba , Interest and Six Hadiths: Do We Have a Definition or a Conundrum? Dr. Mohammad Omar Farooq Associate Professor of Economics and Finance Upper Iowa University June 2006 [Draft; Feedback welcome] The Readers are highly encouraged to read another of my essays "Islamic Law and the Use and Abuse of Hadith " before this one to better follow and appreciate this essay. NOTE for fellow Muslims: Because this topic involves what is haram (prohibited) and halal (permissible) in Islam, every Muslim MUST do his/her own due diligence and conscientiously reach own position/decision in regard to personal practice. In doing so regarding this matter or any other aspect of life, Muslims should seek guidance from the Qur'an and the Prophetic legacy. Each hadith is properly referenced, but for internal reference within this essay, in the sequence presented, each hadith is numbered with # H-. Some of the references in this essay are from secondary sources. As the draft takes it final shape, original sources would be gradually cited and replace the secondary source citations. "There is nothing prohibited except that which God prohibits ... To declare something permitted prohibited is like declaring something prohibited permitted." Ibn Qayyim 1 I. Introduction The Qur'an categorically prohibits riba . However, since there is no unanimity about the definition or scope of this prohibition, we will use the original term riba throughout this essay. In the Qur'an it is specified: Those who devour riba will not stand except as stands one whom the Evil One by his touch hath driven to madness. That is because they say: "Trade is like riba 1 Quoted in Abdulkader Thomas (ed.) Interest in Islamic Economics: Understanding Riba [Routledge, 2006, p. -

10731409.Pdf

ProQuest Number: 10731409 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731409 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 A CRITICAL EDITION of AL-MUTHUL CALA KITAB AL-MUQARRAB FI AL-NAHW by IBN CUSFUR AL-ISHBILI ^VOIJJMEKT ~ ' 1 v o l C/nUj rcccwed //; /.A /• *.' e^ f EDITED by FATHIEH TAWFIQ SALAH Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the University of London School of Oriental and African Studies 1985 Ill TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Dedication ii Table of Contents . iii Thanks Should be Paid v Table of Transliteration vii Abbreviations of Technical Terms viii Illustrations: xii Figure 1 xiii Figure 2 . xiv Abstract xv Introduction xxi Chapter I : The biography of Ibn c Usfur and a brief statement about the political and cultural influences that surrounded his life ................... 1 Chapter II: The works of Ibn c Usfur 16 Chapter III: A critical edition of "Al-Muthul cala Kitab al-Muqarrab": 53 A-The manuscripts which I have relied upon 54 iv Page B-The value of "Al-Muthul cala Kitab al-Muqarrab" 82 C-The method I have followed in edition 85 D-The edition: 89 1-The introduction of the author 90 ✓ v* / o 98 101 3 - tg ili 104 - 113 123 '/ - O /t< / 146 Indexes: 222 1-Verses of the Holy Qur’an ......... -

Commercial Partnership in Islām: a Brief Survey of Kitāb Al-Muḍārabah of Al-Mabsūṭ by Al-Sarakhsī

TAFHIM Online © IKIM Press TAFHIM: IKIM Journal ofCommercial Islam and Partnership the Contemporary in Islam World 11 (2018): 79–111 Commercial Partnership in Islām: A Brief Survey of Kitāb al-Muḍārabah of al-Mabsūṭ by al-Sarakhsī Mohd. Hilmi Ramli* [email protected] Abstract Muḍārabah is a contract of profit-sharing known as partnership in capital and labour. Its concept and practices were notable in the history of Muslims specifically after its incorporation in the fiqh literatures that have spread to the entire education and economic institutions in the Muslim world. It combines two parties: those who have capital and those who are skilful in business to achieve a common economic objective underpinned by the Sharīʿah. This study analyses the work of al- Mabsūṭ by al-Sarakhsī (d. 483 A.H./1090 C.E.), an accomplished Hanafī jurist (fāqih) in the fifth/ eleventh century, pertaining to muḍārabah drawn from the analysis of the first chapter of the book titled Kitāb al-Muḍārabah. This study is significant as it fills the lacuna in the historiography of Islamic economic thought by focusing on al-Sarakhsī’s epistemic framework and definition of muḍārabah, as well as extending in its coverage from the individual * Zamalah UTM Recipient cum PhD candidate at the Centre for Advanced Studies on Islam, Science and Civilisation (CASIS), Technology University of Malaysia (UTM), Kuala Lumpur. 79 TAFHIM Online © IKIM Press Mohd Hilmi / TAFHIM 11 (2018): 79–111 to the institutional. It is a testimony of how Muslims conducted their economic activities based on the intellectual framework and moral guidance underlined by the Sharīʿah. -

Qard Hasan, Credit Cards and Islamic Financial Product Structuring: Some Qur'anic and Practical Considerations

Journal of Islamic Financial Studies ISSN (2469-259X) J. Islam. Fin. Stud. 1, No.1 (Dec-2015) Qard Hasan, Credit Cards and Islamic Financial Product Structuring: Some Qur’anic and Practical Considerations Mohammad Omar Farooq1 and Nedal El Ghattis2 1University of Bahrain, Department of Economics and Finance, Kingdom of Bahrain 2Bahrain Polytechnic, Faculty of Business, Kingdom of Bahrain Received 04 Oct. 2015, Accepted 19 Nov. 2015, Published 1 Dec. 2015 Abstract: For all practical purpose, qard and qard hasan are generally regarded synonymous from orthodox Islamic viewpoint, because, due to the categorical prohibition of riba in the Qur’an, qard (loan) is considered ribawi (subject to the rules pertaining to riba prohibition), and therefore only gratuitous monetary loans – without any benefit to the lender - are considered permissible. The concept of qard hasan has gained new relevance and importance as it is being used to structure Islamic financial products, such as demand deposit products in banks and credit cards. Using qard hasan as the basis for such products leads to some serious anomalies. But more importantly, is the traditional understanding of qard hasan consistent with the Qur’an as well as hadith? What scriptural evidences are there to support the traditional understanding? Also, in light of the impact of credit cards on personal financial health, is the concept ofqard hasan at all compatible with credit cards, and thus, structuring Islamic credit cards? In this paper, we focus on how the Qur’an illuminates this concept of qard hasan and also how it is treated in hadith. While evidence from hadith is looked at, the primary purpose of this paper is to examine the Qur’anic approach to this concept and practical implications for Islamic product structuring. -

Islam and the Foundations of Political Power Ali Abdel Razek

eCommons@AKU In Translation: Modern Muslim Thinkers ISMC Series 1-1-2013 Islam and the Foundations of Political Power Ali Abdel Razek Maryam Loutfi Translator Abdou Filali-Ansary Editor Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_intranslation Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons Recommended Citation Abdel Razek, A. , Loutfi, M. , Filali-Ansary, A. (2013). Islam and the Foundations of Political Power Vol. 2, p. 144. Available at: http://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_intranslation/1 IN TRANSLATION: MODERN MUSLIM THINKERS Established in London in 2002, the Aga Khan University, Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations aims to strengthen research and teaching about the heritages of Muslim societies as they have evolved over time, and to examine the challenges these societies face in today’s globalised world. It also seeks to create opportunities for interaction among academics, traditionally trained scholars, innovative thinkers and leaders, in an effort to o I promote dialogue and build bridges. s f l a P IN TRANSLATION: MODERN MUSLIM THINKERS m o Islam and the Series Editor: Abdou Filali-Ansary l a i This series aims to broaden current debates about Muslim realities which often ignore seminal t n works produced in languages other than English. By identifying and translating critical and i c innovative thinking that has engendered important debates within its own settings, the series d Foundations of a hopes to introduce new perspectives to the discussions about Muslim civilisations -

Important Coins of the Islamic World

Important Coins of the Islamic World To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Lower Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Day of Sale: Thursday 2 April 2020 at 12.00 noon Public viewing: Nash House, St George Street, London W1S 2FQ Monday 30 March 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 31 March 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 1 April 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 107 Price £15 Enquiries: Stephen Lloyd or Tom Eden Cover illustrations: Lots 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (front); lots 43, 63 (back); A selection of coins struck in Makka (inside front); lots 26, 27 (inside back) Nash House, St George Street, London W1S 2FQ Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Online Bidding This auction can be viewed online at www.invaluable.com, www.numisbids.com, www.emax.bid and www. biddr.ch. Morton & Eden Ltd offers live online bidding via www.invaluable.com. Successful bidders using this platform will be charged a fee of 3.6% of the hammer price for this service, in addition to the Buyer’s Premium fee of 20%. This facility is provided on the understanding that Morton & Eden Ltd shall not be responsible for errors or failures to execute internet bids for reasons including but not limited to: i) a loss of internet connection by either party ii) a breakdown or other problems with the online bidding software iii) a breakdown or other problems with your computer, system or internet connection.