Numismatic and Monetary Aspects of Introducing the Uniform European Union Currency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Monetary History of the Former German Colony of Kiaochou

A MONETARY HISTORY OF THE FORMER GERMAN COLONY OF KIAOCHOU John E. Sandrock After China’s crushing defeat by Great Britain and France in the two Opium Wars (1839-1842 and 1856-1858), the Ch’ing dynasty fell into great decline. After both of these events, the Manchu government was forced to sue for peace – the price of which proved to be very dear indeed. Great Britain and France, sensing the total collapse of civil rule in China, placed exorbitant demands upon China in the form of repatriations as laid down in the Treaty of Nanking. These took two distinct forms; the demand for monetary indemnity in silver for expenditures incurred in the war, and for the outright concession of Chinese territory. The Chinese eventually handed over twenty-one million ounces of silver to satisfy the former, and the island of Hong Kong to satisfy the latter. Thus the British territory of Hong Kong was created. This act proved the forerunner of additional demands for territorial concessions on the part of the European powers and Japan, who then proceeded to carve China up into various spheres of influence for commercial exploitation. French territorial ambitions centered upon south China. The British, in addition to their trading port of Hong Kong, sought the right to open additional Yangtze River ports to trade. Russia had ambitions for territorial expansion in the north, where she craved a warm water Russian port on the Liaotung peninsula as well as land in Manchuria. The Japanese, seizing upon the opportunity, laid claim to Korea and the offshore island of Taiwan, which was then renamed Formosa. -

HARMONY Or HARMONEY

Niklot Kluessendorf Harmony in money – one money for one country ICOMON e-Proceedings (Shanghai, 2010) 4 (2012), pp. 1-5 Downloaded from: www.icomon.org Harmony in money – one money for one country Niklot Klüßendorf Amöneburg, Germany [email protected] This paper discusses the German reforms from 1871 to 1876 for 26 States with different monetary traditions. Particular attention is paid to the strategy of compromise that produced harmony, notwithstanding the different traditions, habits and attitudes to money. Almost everybody found something in the new system that was familiar. The reform included three separate legal elements: coinage, government paper money and banknotes, and was carried out in such a way to avoid upsetting the different parties. Under the common roof of the new monetary unit, traditional and regional elements were preserved, eg in coin denominations, design, and even in the colours of banknotes. The ideas of compromise were helpful to the mental acceptance of the new money. As money and its tradition are rooted in the habits and feelings of the people, the strategy of creating harmony has to be taken into consideration for many monetary reforms. So the German reforms were a good example for the euro that was introduced with a similar spirit for harmony among the participating nations. New currencies need intensive preparation covering political, economic and technical aspects, and even psychological planning. The introduction of the euro was an outstanding example of this. The compromise between national and supranational ideas played an important role during the creation of a single currency for Europe. Euro banknotes, issued by the European Central Bank, demonstrate the supranational idea. -

Number 37 May 2000 Euro Coins from Design to Circulation

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Number 37 May 2000 (XURFRLQV From design to circulation © European Communities, 2000. (XURFRLQV )URPGHVLJQWRFLUFXODWLRQ 'LUHFWRUDWH*HQHUDOIRU(FRQRPLFDQG)LQDQFLDO$IIDLUV EURO COINS 7+(/(*$/%$6(6 7KH7UHDW\ 7KHWZR5HJXODWLRQVRI0D\ &5($7,1*7+((852&2,16 &KRRVLQJWKHQDPH &KRRVLQJWKHGHQRPLQDWLRQVRIWKHFRLQV 'HWHUPLQLQJWKHWHFKQLFDOVSHFLILFDWLRQVRIWKHFRLQV &KRRVLQJWKHFRPPRQVLGHRIWKHFRLQV &KRRVLQJWKHQDWLRQDOVLGHRIWKHFRLQV &UHDWLQJFROOHFWRUFRLQV…………………………………………………………………………..16 352'8&,1*7+((852&2,16 'HWHUPLQLQJWKHTXDQWLWLHVWRSURGXFH &RQWUROOLQJTXDOLW\ 3527(&7,1*7+((852&2,16« )LOLQJDFRS\ULJKWRQWKHFRPPRQVLGHV 3UHYHQWLQJDQGVXSSUHVVLQJFRXQWHUIHLWLQJ ,1752'8&,1*7+((852&2,16 )LQDOLVLQJWKHVFKHGXOHIRUWKHLQWURGXFWLRQRIWKHFRLQV 'HILQLQJWKHOHQJWKRIWKHSHULRGRIGXDOFLUFXODWLRQ ,1)250$7,216+((76 1R7KHFKRLFHRIWKHHXURV\PERO««««««««««««««««««««««««« 1R6LWXDWLRQRI0RQDFR9DWLFDQ&LW\DQG6DQ0DULQR« 1R8VHIXO,QWHUQHWOLQNV« 1R$GGUHVVHVDQGFRQWDFWVRIWKHFRLQWHVWLQJFHQWUHV« $11(;(6 $UWLFOH H[D RIWKH7UHDW\HVWDEOLVKLQJWKH(XURSHDQ&RPPXQLW\« &RXQFLO5HJXODWLRQ (& 1RRI0D\RQWKHLQWURGXFWLRQRIWKHHXUR &RXQFLO 5HJXODWLRQ (& 1R RI 0D\ RQ GHQRPLQDWLRQV DQG WHFKQLFDO VSHFLILFDWLRQV RI HXUR FRLQV LQWHQGHGIRUFLUFXODWLRQ««« 2/45 &RXQFLO5HJXODWLRQ (& 1RRI)HEUXDU\DPHQGLQJ5HJXODWLRQ (& 1RRQGHQRPLQDWLRQV DQGWHFKQLFDOVSHFLILFDWLRQVRIHXURFRLQVLQWHQGHGIRUFLUFXODWLRQ««««««««« &RPPLVVLRQ5HFRPPHQGDWLRQRI-DQXDU\FRQFHUQLQJFROOHFWRUFRLQVPHGDOVDQGWRNHQV«« 5HSRUWIURPWKH&ROOHFWRU&RLQ6XEJURXSRIWKH0':*IRUWKH(XUR&RLQ6XEFRPPLWWHHRIWKH()&«« &RXQFLO 'HFLVLRQ RI $SULO H[WHQGLQJ (XURSRO V PDQGDWH -

Udl-Juni Vejl2015

UOFICIELLE KURSER VEJLEDENDE - UDEN FORBINDENDE Juni LAND LANDEKODE MØNTENHED a' KURS PR. 100 ENH. AFGHANISTAN AFA AFGHANI 100 PULS 11,17 ALBANIEN ALL LEK 100 QUINDARKA 5,328 ALGERIET DZD ALGIERSK DINAR 100 CENTIMES 6,755 ANDORRA EUR EURO 100 CENT (A) ANGOLA AOA KWANZA 100 IWEI 5,521 ARGENTINA ARS PESO 100 CENTAVOS 73,38 ARMENIEN AMD DRAM 100 LUMA 1,415 ARUBA AWG ARUBA GYLDEN 100 CENT 372,49 ASERBAJDSJAN AZM ASERB.MANAT 100 GOPIK 639,14 AZORERNE EUR EURO 100 CENT (A) BAHAMA ØERNE BSD BAHAMA DOLLAR 100 CENTS 666,75 BAHRAIN BHD BAHRAIN DINAR 1000 FILS 1768,50 BANGLADESH BDT TAKA 100 PAISA 8,577 BARBADOS BBD BARBADOS DOLLAR 100 CENTS 333,37 BELIZE BZD BELIZE DOLLAR 100 CENTS 333,37 BENIN XOF C.F.A. FRANCE 100 CENTIMES 1,1370 BERMUDA BMD BERMUDA DOLLAR 100 CENT 666,75 BHUTAN BTN NGULTRUM 100 CHETRUM 10,47 INDISK RUPEE 1 ) 100 CHETRUM/PAISA BOLIVIA BOB BOLIVIANO 100 CENTAVOS 97,47 BOSNIEN-HERCEGOVINA BAM BOSN.MARK 100 PFENNIG 380,94 BOTSWANA BWP PULA 100 THEBE 67,34 BRASILIEN BRL REAL 100 CENTAVOS 213,59 BRUNEI BND BRUNEI DOLLAR 100 SEN 495,25 BURKINA FASO XOF C.F.A. FRANCE 100 CENTIMES 1,1370 BURUNDI BIF BURUNDI FRANC 100 CENTIMES 0,4305 CAMBODIA KHR RIEL 100 SEN 0,1653 CAMEROUN XAF C.F.A. FRANC 100 CENTIMES 1,1370 CAYMAN ØERNE KYD CAYMAN ISLAND DOLLAR 100 CENT 813,12 CENTRALAFRIKANSKE REP. XAF C.F.A. FRANC 100 CENTIMES 1,1370 CHILE CLP CHILE PESO 100 CENTAVOS 1,0430 COLOMBIA COP COLOMBIA PESO 100 CENTAVOS 0,2582 COMORE ØERNE KMF COMORE FRANCE 100 CENTIMES 1,5250 CONGO XAF C.F.A. -

Explaining the September 1992 ERM Crisis: the Maastricht Bargain and Domestic Politics in Germany, France, and Britain

Explaining the September 1992 ERM Crisis: The Maastricht Bargain and Domestic Politics in Germany, France, and Britain Explaining the September 1992 ERM Crisis: The Maastricht Bargain and Domestic Politics in Germany, France, and Britain Christina R. Sevilla Harvard University Dept. of Government Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] Presented at the European Community Studies Association, Fourth Biennial International Conference, May 11-14, 1995, Charleston, SC. Comments welcome. In September of 1992, the seemingly inexorable movement of the European exchange rate mechanism from a system of quasi-fixed exchange rates towards monetary union and ultimately a common currency by the end of the decade was abruptly preempted, perhaps indefinitely. Massive speculative pressure on the eve of the French referendum precipitated the worst crisis in the thirteen- year history of the European Monetary System, resulting in the ejection of the sterling and the lira from the ERM, the devaluation of the peseta, the threat of forced devaluation of several other currencies, including the "hard-core" franc, and the abandonment or near-abandonment of unilateral currency pegs to the system by non-ERM countries. Together with political recriminations and blame-laying between Britain and Germany in the aftermath, the crisis represented a tremendous blow to the goals of political and economic integration recently affirmed by EC member governments in the Maastricht Treaty on European Union in December 1991. Nevertheless, conventional wisdom at the time dictated a more sanguine assessment of the prospects for EMU, in the belief that the strains within the ERM were due to the unfortunate confluence of exceptional circumstances -- the shock of German reunification, a debt-driven recession in Britain, and the uncertainties caused by the Danish and French referendums on Maastricht. -

V. Exchange Rates and Capital Flows in Industrial Countries

V. Exchange rates and capital flows in industrial countries Highlights Two themes already evident in 1995 persisted in the foreign exchange market last year. The first was the strengthening of the US dollar, in two phases. In spite of continuing trade deficits, the dollar edged up for much of 1996 as market participants responded to its interest rate advantage, and the prospect of its increasing further. Then, towards the end of the year, the dollar rose sharply against the Deutsche mark and the Japanese yen as the US economic expansion demonstrated its vigour. A firming of European currencies against the mark and the Swiss franc accompanied the rise of the dollar. This helped the Finnish markka to join and the Italian lira to rejoin the ERM in October and November respectively. Stronger European currencies and associated lower bond yields both anticipated and made more likely the introduction of the euro, the second theme of the period under review. Market participants clearly expect the euro to be introduced: forward exchange rates point to exchange rate stability among a number of currencies judged most likely to join monetary union. Foreign exchange markets thereby stand to lose up to 10¤% of global transactions, and have begun to refocus on the rapidly growing business of trading emerging market currencies. Possible shifts in official reserve management with the introduction of the euro have preoccupied market commentators, but changes in private asset management and global liability management could well prove more significant. Even then, it is easy to overstate the effect of any such portfolio shifts on exchange rates. -

First Law on Currency Reform (20 June 1948)

First law on currency reform (20 June 1948) Caption: On 20 June 1948, the first law on currency reform in the US, British and French occupation zones specifies the conditions for the introduction of the new German currency, the Deutschmark. Source: United States-Department of State. Documents on Germany 1944-1985. Washington: Department of State, [s.d.]. 1421 p. (Department of State Publication 9446). p. 147-148. Copyright: United States of America Department of State URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/first_law_on_currency_reform_20_june_1948-en-a5bf33f8-fca0-4234-a4d2- 71f71a038765.html Last updated: 03/07/2015 1 / 3 03/07/2015 Summary of the First Law of Currency Reform Promulgated by the Three Western Military Governors, Effective June 20, 1948 The first law of the reform of the German currency promulgated by the Military Governments of Great Britain, the United States, and France will go into effect on June 20. The old German currency is hereby invalidated. The new currency will be the deutsche mark which will be divided into 100 deutsche pfennig. The old money, the reichsmark, the rentenmark and mark notes issued in Germany by the Allied Military authorities, will become invalid on June 21. The only exceptions are old mark notes and coins up to a denomination of one mark. In order to prevent a temporary shortage of small change, these small notes and coins will remain in use until further notice at one tenth their old or nominal value. Nobody, however, need accept more than 50 pieces of small change in payment of any kind. Postage stamps will also remain valid at one tenth their nominal value. -

$ 0.20) ($ 13.00) Canada ($ 0.10) ($ 2.10

Country Denomination Total US Equivalent Total Value Canada ($ 0.25) ($ 16.25) ($ 0.20) ($ 13.00) Canada ($ 0.10) ($ 2.10) ($ 0.10) ($ 2.10) Canada ($ 0.05) ($ 1.40) ($ 0.05) ($ 1.40) Canada ($ 0.01) ($ 0.14) ($ 0.01) ($ 0.14) Canada ($ 1.00) ($ 5.00) ($ 0.79) ($ 3.95) Canada 2 Dollar 6 Dollar ($ 1.58) ($ 4.74) ? 10 Pence 40 Pence ($ 0.10) ($ 0.40) ? 5 Pence 25 Pence ($ 0.01) ($ 0.05) ? 20 Pence 40 Pence ($ 0.33) ($ 0.66) ? 2 Pence 2 Pence ($ 0.03) ($ 0.03) Canada 50 Pence 50 Pence ($ 0.70) ($ 0.70) Cayman Island ($ 0.25) ($ 1.50) ($ 0.30) ($ 1.80) Bahamas ($ 0.25) ($ 2.75) ($ 0.25) ($ 2.75) Bahamas ($ 0.10) ($ 0.20) ($ 0.10) ($ 0.20) Bahamas ($ 0.05) ($ 0.15) ($ 0.05) ($ 0.15) Bermuda ($ 0.25) ($ 0.25) ($ 0.25) ($ 0.25) Australia 10 Pence? 20 Pence? ($ 0.10) ($ 0.20) Belize ($ 0.25) ($ 0.25) ($ 0.12) ($ 0.12) Barbados ($ 0.25) ($ 0.25) ($ 0.12) ($ 0.12) Barbados ($ 1.00) ($ 1.00) ($ 0.50) ($ 0.50) Cuba ($ 0.25) ($ 0.25) ($ 0.01) ($ 0.01) Jamaica ($ 10.00) ($ 10.00) ($ 0.07) ($ 0.07) Jamaica ($ 1.00) ($ 1.00) ($ 0.01) ($ 0.01) Phillipines 25 Sentimo 75 Sentimo ($ 0.01) ($ 0.02) Phillipines 1 Peso 2 Peso ($ 0.02) ($ 0.02) Mexico ($ 1.00) ($ 11.00) ($ 0.05) ($ 0.55) Mexico ($ 2.00) ($ 6.00) ($ 0.10) ($ 0.30) Mexico ($ 5.00) ($ 20.00) ($ 0.25) ($ 1.00) Poland 5 Zlotych 5 Zlotych ($ 1.35) ($ 1.35) Singapore ($ 0.10) ($ 0.50) ($ 0.08) ($ 0.40) Aruba ($ 0.25) ($ 0.50) ($ 0.14) ($ 0.28) Country Denomination Total US Equivalent Total Value Aruba ($ 0.10) ($ 0.10) ($ 0.06) ($ 0.06) Costa Rica 5 Colones 5 Colones ($ 0.01) ($ 0.01) Costa Rica 10 -

Auc28sesdweb.Pdf

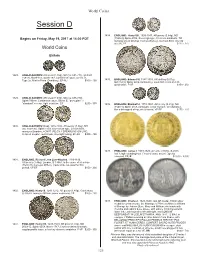

World Coins Session D 1434. ENGLAND: Henry VIII, 1509-1547, AR penny (0.64g), ND Begins on Friday, May 19, 2017 at 14:00 PDT [1526-9], Spink-2352, Sovereign type, Crescent mintmark, TW flanking shield (Bishop Thomas Wolsey), Durham Mint, tiny clip at 7:00, VF $125 - 175 World Coins Britain 1428. ANGLO-SAXONS: AR sceat (1.16g), ND (ca. 695-715), Metcalf 158-70, North-163, Spink-792, Continental issue, Series D, Type 2c, Mint in Frisia (Domberg), EF-AU $100 - 150 1435. ENGLAND: Edward VI, 1547-1553, AR shilling (6.01g), ND [1551], Spink-2482, mintmark y, small flan crack at 2:30, good strike, F-VF $350 - 450 1429. ANGLO-SAXONS: AR sceat (1.04g), ND (ca. 695-740), Spink-790var, Continental issue, Series E, “porcupine” // “standard” reverse, light oxidation, EF $250 - 350 1436. ENGLAND: Elizabeth I, 1558-1603, AR penny (0.41g), ND [1560-1], Spink-2558, mintmark: cross-crosslet, second issue, flan a bit ragged at top, nicely toned, VF-EF $175 - 225 1430. ANGLO-SAXONS: Cnut, 1016-1035, AR penny (1.06g), ND (ca. 1029-36), Spink-1159, short cross type, Lincoln Mint, moneyer Swartinc, +CNVT .RE:CX // SPEARLINC ON LINC, lis tip on scepter, well struck, nice light toning, EF-AU $300 - 400 1437. ENGLAND: James I, 1603-1625, AV unite (9.63g), S-2618, half-length standing bust // coat of arms, mount expertly removed, EF, R $2,600 - 3,000 1431. ENGLAND: Richard I, the Lion-Hearted, 1189-1199, AR penny (1.44g), London, S-1348A, in the name of Henricus (Henry II), moneyer Willem, crude strike as usual for this period, VF-EF $150 - 200 1432. -

Platts Market Data User Guide

Platts www.spglobal.com/platts Market Data User guide Febuary 2019 Release 4.6v1 Contents 1 Introduction 1.1 Platts Market Data/Delivery ................................................................................................................................. 3 2 Market Data delivery schedules 2.1 Market Data schedules general information ...................................................................................................... 5 2.2 General Market Data file notes ............................................................................................................................ 5 2.3 Market Data sFTP notes ....................................................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Market Data .csv notes ......................................................................................................................................... 7 2.5 ‘Flow Date’ and Future-dated values, and the 12:45am cut .............................................................................. 8 3. Accessing Platts Market Data 3.1 Platts Market Data via sFTP ................................................................................................................................ 9 3.2 Platts Market Data .csv files via www.spglobal.com/platts ........................................................................... 13 4 Market Data FTP data file formats 4.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Währungssymbol – Wikipedia

6.2.2018 Währungssymbol – Wikipedia Währungssymbol Ein Währungssymbol (oder Währungszeichen) ist ein besonderes Schriftzeichen, das als Abkürzung für eine Währung verwendet wird. Es wird entweder nach (12,80 €) oder vor dem Betrag ($ 12,80) geschrieben. Es wird ein oder kein Leerzeichen zwischen Symbol und Betrag gesetzt (sprachabhängig).[1][2][3] In Portugal und Frankreich wurden die Währungssymbole vor Einführung des Euro auch als Dezimaltrennzeichen in dem Betrag verwendet (12₣80). Um Verwechslungen auszuschließen, werden Währungssymbole, die für mehrere Währungen gelten, auch zusammen mit Buchstabenkürzeln verwendet (beispielsweise US-$, US$). Im internationalen Zahlungsverkehr werden Abkürzungen nach ISO 4217 ihrer Eindeutigkeit wegen bevorzugt; auch sind sie mit Informationstechnik austauschbar und Symbole aus fremden Kulturkreisen werden oft nicht verstanden. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/W%C3%A4hrungssymbol 1/4 6.2.2018 Währungssymbol – Wikipedia Tabelle der Währungssymbole ¤ Allgemeines Währungssymbol (Platzhalter für eine noch konkret zu ergänzende Währung) Altyn (ehemalige russische Münze) ₳ Austral (ehemalige argentinische Währung) ฿ Baht (Thailand) ฿ Balboa (Panama) B/. $ Boliviano (Bolivien) ₵ Cedi (Ghana) ¢ Cent (wird für US- und einige andere Cents benutzt, jedoch nicht für den Eurocent) ₡ Colón (Costa Rica CRC; SVC ehemalige Währung in El Salvador) ₢ Cruzeiro (ehemalige Währung in Brasilien) Dollar (Anguilla, Antigua und Barbuda, Australien, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bermuda, Brunei, Dominica, Ecuador, Fidschi, Grenada, -

Note on Currencies and Other Abbreviations

Note on Currencies and Other Abbreviations erman economic history is a very complicated subject, which Gthis author cannot claim to have fully mastered. Some of the complexities include the multiple currencies used by inhabitants of the myriad states of central Eu rope until the later nineteenth century (when these were at least stabilized, though not united), the chang- ing of units of exchange over time, and the very differ ent “real” value of coins, especially before 1815. Although an agreement was made in the mid-sixteenth century that all states of the Holy Roman Empire that issued reichstaler would maintain its silver content at 25.98 grams of silver,1 in practice these were often clipped or the silver or gold mixed with cheaper alloys. A taler being a relatively large coin, each state could also issue its own smaller coins, in amounts left to their own discretion, making for a proliferation of fractional currencies (the most common being the groschen and the pfennig; twelve pfennig were equal to one groschen, and twenty- four groschen made up the taler). Between 1754 and 1892, Austria de- nominated its currency in florins (F), often called gulden, whichwere further divided into one hundred heller; after 1892, the Austrian cur- rency became the krone, worth .5 of a florin. The schilling (S) was introduced in 1924 and divided into one hundred groschen; this gave way to the reichsmark after Germany’s annexation of Austria in 1938 but was reinstated in 1945. Some of the southern states, such as Bavaria, traded in gulden (G). As the