Intra-Regional Trade and African Economic Integration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role and Function of Regional Blocs and Arrangements in the Formation of the Islamic Common Market

Journal of Economic Cooperation 21 , 4 (2000) 1-28 ROLE AND FUNCTION OF REGIONAL BLOCS AND ARRANGEMENTS IN THE FORMATION OF THE ISLAMIC COMMON MARKET ∗ Oker Gürler The present study aims to examine the role and function of regional blocs and trade arrangements in the formation of the Islamic Common Market. For this purpose, it provides, first of all, a conceptual background on regional economic groupings. Then, it evaluates the regional economic groupings and trade arrangements formed amongst the member countries of the OIC. Based on this framework, the paper discusses, in detail, the possible role and function of regional economic groupings and trade arrangements in the formation of the Islamic Common Market or any other form of economic integration. At the end, it gives concluding remarks on the topic. 1. INTRODUCTION In the 1990s, regionalisation efforts increased considerably at the global scale. This new wave of regionalisation was mostly affected by the achievements of the European countries in creating first a common market and then a monetary and economic union amongst themselves. Since its establishment, the European Union (EU) has grown greatly in terms of its membership, its economic and political influence, and its organisational infrastructure. Starting with only six member states, its membership has now reached fifteen. Furthermore, more countries are waiting at the doorstep of the Union. On the other hand, the Maastricht Summit (9-10 December 1991) was a very important turning point in the history of the EU. The member countries agreed on the Treaty on the European Union aiming to develop the European Community into an Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and to introduce a single European currency by 1999 at the latest. -

Download PDF (650.9

IMF Working Paper This is a Working Paper and the author(s) would welcome any comments on the present text. Citations should refer to a Working Paper o/the International Monetary Fund. The © 1998 International Monetary Fund views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the Fund. WP/98/84 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND IMF Institute Trading Blocs and Welfare: How Trading Bloc Members Are Affected by New Entrants Prepared by R. Scott Hacker and Qaizar Hussainl Authorized for distribution by B.R.H.S. Rajcoomar June 1998 Abstract This paper uses the three-country duopoly model to examine the effects of lowered trade barriers when a new entrant joins a trading bloc. There are two firms-a small-country firm and a large-country firm within the bloc-and three markets-two within and one (new entrant's) outside the bloc. The analysis generally shows greater gains for the small-country than for the large-country firm. The small-country firm will export more to the external country than the large-country firm. But if tariffs decline, the export share of the large-country firm will increase relative to the small-country firm's, though profits will improve more for the latter. JEL Classification Numbers: F15, FlO, D43, D60 Keywords: Trading Blocs, Duopoly, Tariffs Author's E-Mail Address: [email protected] 1 R. Scott Hacker is at the Jbnkbping International Business School, Sweden. The authors are grateful to Mohsin Khan, Timo Valila, Philip Wong, Hassan Al-Atrash, Ashok Bardhan, Ernesto Stein, Thomas Dorsey, and Clas Wihlborg for valuable comments. -

Download PDF (54.2

IMF Working Paper This is a Working Paper and the author(s) would welcome any comments on the present text. Citations should refer to a Working Paper o/the International Monetary Fund. The © 1998 International Monetary Fund views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the Fund. WP/98110 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND Research Department Open Regionalism in a World of Continental Trade Blocs Prepared by Jeffrey Frankel and Shang-Jin Weil Authorized for distribution by Donald J. Mathieson February 1998 Abstract Continental trade blocs are emerging in many parts of the world almost in tandem. Iftrade blocs are required to satisfy the McMillan criterion of not lowering trade volume with outside countries, they have to engage in a dramatic reduction of trade barriers against non-member countries. That may not be politically feasible. On the other hand, in a world of simultaneous continental trade blocs, an open regionalism in which trade blocs undertake relatively modest external liberalization can usually produce Pareto improvement. JEL Classification Numbers: F15 Keywords: Open regionalism, trade blocs, the McMillan criterion. Author's E-Mail Address: [email protected] Http://www. nber. org/~wei lJeffrey Frankel is Chief Economist, u.s. President's Council of Economic Advisers, and Professor of Economics, University of California, Berkeley. Shang-Jin Wei is Associate Professor of Public Policy, Harvard University. Part of the research for the paper was completed when Prof Wei was a visiting scholar at the IMF's Research Department. We would like to thank Alan Winters and T.N. Srinivasan for helpful comments, Jungshik Kim and Greg Dorchak for efficient research and editorial assistance, and the Pacific Basin Research Center of Soka University, operating out of Harvard University, for financial support. -

Border Operating Model

UK border changes from 1st January 2021 Impact on flow of UK-EU goods AGENDA ❑ How we got here ❑ Trade agreement landscape before and after 31st December 2020) ❑ UK Government’s Border Operating Model – Explained ❑ Importers: phased implementation; facilitations and simplifications; actions ❑ Exporters: no phased implementation; immediate requirements; facilitations and simplifications; actions ❑ Available information and support TRADING IN GOODS CURRENTLY (EXAMPLE) FACTS AND HOW WE GOT TO WHERE WE ARE NOW HOW WE GOT HERE 29th January 2020 30th June 2020 European Parliament gives UK declines to request an its consent to the extension to the transition 22nd October 2019 withdrawal agreement; period by date mandated Revised withdrawal subsequently concludes by in Article 132 of the 23rd June 2016 22nd March 2019 agreement is cleared first the Council of the Withdrawal Agreement. UK votes to leave UK and EU agree on an stage in UK Parliament – European Union on 30th Transition period end 31st the EU initial extension GE election called. January 2020. December 2020 rd st 29th March 2017 11th April 2019 23 January 2020 31 January 2020 UK serves notice of its EU extends the date of the UK Parliament ratifies the UK officially leaves the EU withdrawal to the EU exit until 31st October agreement by passing the and 11-month transition starting a two-year process 2019. This is done at the Withdrawal Agreement Act period began whereby the UK would request of and in automatically leave the EU agreement with the UK on 29th March 2019 IMPACT OF NO AGREEMENT -

The Eurasian Union the Eurasian Union: Future of Integration Or Failure in the Making

Proceedings of GREAT Day Volume 2017 Article 6 2018 The urE asian Union: Future of Integration or Failure in the Making Maria Gershuni SUNY Geneseo Follow this and additional works at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/proceedings-of-great-day Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Gershuni, Maria (2018) "The urE asian Union: Future of Integration or Failure in the Making," Proceedings of GREAT Day: Vol. 2017 , Article 6. Available at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/proceedings-of-great-day/vol2017/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the GREAT Day at KnightScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of GREAT Day by an authorized editor of KnightScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gershuni: The Eurasian Union The Eurasian Union: Future of Integration or Failure in the Making Maria Gershuni Sponsored by Robert Goeckel ABSTRACT e idea of the Eurasian Economic Union, or the EEU, was rst brought up by Kazakhstan’s President Nursultan Nazerbaev in 1994. By 2015, the Russian Federation, Belarus, and Kazakhstan signed the Treaty for the Establishment of the EEU, making the idea a reality. e EEU currently occupies nearly 15% of the earth’s land, and is the 12th largest economy in the world. However, very little is known about this integration project. Criticized as Russian President Vladimir Putin’s pet project, and a hollow imitator of the European Union, the EEU now faces challenges of imbalance, inequity, and further integration. -

China's Belt and Road Initiative in the Global Trade, Investment and Finance Landscape

China's Belt and Road Initiative in the Global Trade, Investment and Finance Landscape │ 3 China’s Belt and Road Initiative in the global trade, investment and finance landscape China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) development strategy aims to build connectivity and co-operation across six main economic corridors encompassing China and: Mongolia and Russia; Eurasian countries; Central and West Asia; Pakistan; other countries of the Indian sub-continent; and Indochina. Asia needs USD 26 trillion in infrastructure investment to 2030 (Asian Development Bank, 2017), and China can certainly help to provide some of this. Its investments, by building infrastructure, have positive impacts on countries involved. Mutual benefit is a feature of the BRI which will also help to develop markets for China’s products in the long term and to alleviate industrial excess capacity in the short term. The BRI prioritises hardware (infrastructure) and funding first. This report explores and quantifies parts of the BRI strategy, the impact on other BRI-participating economies and some of the implications for OECD countries. It reproduces Chapter 2 from the 2018 edition of the OECD Business and Financial Outlook. 1. Introduction The world has a large infrastructure gap constraining trade, openness and future prosperity. Multilateral development banks (MDBs) are working hard to help close this gap. Most recently China has commenced a major global effort to bolster this trend, a plan known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China and economies that have signed co-operation agreements with China on the BRI (henceforth BRI-participating economies1) have been rising as a share of the world economy. -

Trade Statistics in Policymaking

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Trade Statistics in Policymaking - A HANDBOOK OF COMMONLY USED TRADE INDICES AND INDICATORS - Revised Edition Prepared by Mia Mikic and John Gilbert Trade Statistics in Policymaking - A HANDBOOK OF COMMONLY USED TRADE INDICES AND INDICATORS - Revised Edition United Nations publication Copyright © United Nations 2009 All rights reserved ST/ESCAP/ 2559 The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The opinions, figures and estimates set forth in this publication are the responsibility of the authors and should not necessarily be considered as reflecting the views or carrying the endorsement of the United Nations. Mention of firm names and commercial products does not imply the endorsement of the United Nations. All material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgment is required, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint. The use of this publication for any commercial purpose, including resale, is prohibited unless permission is first obtained from the secretary of the Publication Board, United Nations, New York. Requests for permission should state the purpose and the extent of reproduction. This publication has been issued without -

The Effect of Common Currency on Economic Growth: Evidence from CEMAC Custom Union," African Social Science Review: Vol

African Social Science Review Volume 10 | Number 1 Article 5 May 2019 The ffecE t of Common Currency on Economic Growth: Evidence from CEMAC Custom Union Divine N. Kangami University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, [email protected] Oluyele A. Akinkugbe University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.tsu.edu/assr Recommended Citation Kangami, Divine N. and Akinkugbe, Oluyele A. (2019) "The Effect of Common Currency on Economic Growth: Evidence from CEMAC Custom Union," African Social Science Review: Vol. 10 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.tsu.edu/assr/vol10/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Scholarship @ Texas Southern University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African Social Science Review by an authorized editor of Digital Scholarship @ Texas Southern University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The ffecE t of Common Currency on Economic Growth: Evidence from CEMAC Custom Union Cover Page Footnote Considerable thanks goes to the National Research Foundation (NRF), South Africa for granting us the financial support to pursue and complete this article. Also, we will like to extend our sincere appreciation to Prof George Klay Kieh, Jr, President of the African Studies and Research Forum, Prof Abdul Karim Bangura of the American University Center for Global Peace and Prof Ishmael I. Munene of Northern Arizona University for their encouragement and guidance. This article is available in African Social Science Review: https://digitalscholarship.tsu.edu/assr/vol10/iss1/5 Kangami and Akinkugbe: Effect of Common Currency on CEMAC Custom Union’s Economic Growth African Social Science Review Volume 10, Number 1, Spring 2019 The Effect of Common Currency on Economic Growth: Evidence from CEMAC Custom Union Divine N. -

Introduction the Eurasian Economic Union, Abbreviated by EAEU Or

EAEU Introduction Member Countries The Eurasian Economic Union, abbreviated by EAEU or Armenia Kyrgyzstan December 2010 - The Declaration on Establishment of the EEU, is an international economic union of countries located Belarus Russia Single Economic Space of the Republic of Belarus, the in northern Eurasia. The EAEU provides for the free Kazakhstan Republic of Kazakhstan and the Russian Federation was movement of goods, services, capital, and labor; and signed. pursues coordinated, harmonized, and single policy in the History 2011 - A decision was made to start negotiations on the specified sectors of the economy. The economic union was accession of the Kyrgyz Republic to the Customs Union. established via the Treaty on the Eurasian Economic Union March 1994 - Kazakhstani President, Nursultan Nazarbayev and entered into force on January 1, 2015. The founding first suggests the idea of creating a regional trade bloc 2012 - The treaties entered into force, providing the legal member states are Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia. Both during a speech at Moscow State University. framework for the Single Economic Space of the Republic of Armenia and Kyrgyzstan signed accession treaties with the Belarus, the Republic of Kazakhstan and the Russian June 1994 - A detailed integration project was submitted to EAEU in 2014, which entered into force on January 2, 2015 Federation and also ensuring free movement not only of the Heads of States. The integration alliance was referred to and August 12, 2015 respectively. The main objectives of goods, but also of services, capital, and labor. as "The Eurasian Union". the EAEU are to upgrade the competitiveness of the May 2014 - Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia sign the member states economies, increase cooperation among 1995 - Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia sign the Treaty on Treaty on the Eurasian Economic Union thus establishing member states, and to promote stable development in order the Customs Union, which was aimed at eliminating any the Eurasian Economic Union. -

FERDI-P27-Getting the Best out of Regional Integration

king Pape or r W • • s fondation pour les études et recherches sur le développement international e D 27 i e September ic ve 2011 ol lopment P Getting the Best out of Regional Integration: Some Thoughts for Rwanda * Jaime de Melo Laura Collinson Jaime de Melo was Professor at the University of Geneva from 1993 to 2012. His research focuses on trade policies, on trade and the environment, on the links between regionalism and multilateralism. He is Senior Fellow at Ferdi since 2011. » Laura Collinson is an Associate at the Toronto office of the Boston Consulting Group. Prior to this, she was an In-Country Economist in the International Growth Centre’s Rwanda country office. ANR-10-LABX-14-01 Executive Summary Rwanda has made much progress towards integrating into the world economy, » PORTANT LA RÉFÉRENCE « » PORTANT with yearly export growth rates close to 20%. However, largely because of being landlocked, Rwanda is still isolated from many trading partners and, because of the low share of trade in GDP, exports do not contribute much to overall growth. In its Vision 2020, the GOR decided to push for the “Promotion of Re- gional Economic Integration and Cooperation”. This paper argues that this was, INVESTISSEMENTS D’AVENIR INVESTISSEMENTS and continues to be, the right strategy to pursue. … /… * This paper had been funded by the IGC. It is a revised version of a paper presented at the IGC Growth Forum, “Transi- tioning from Take-off to Sustained Growth”, Kigali, February 17, 2011. We thank Richard Newfarmer and participants at the Forum for helpful comments on the earlier version. -

Regional Trading Blocs in the World Economic System

Appendix A An Outline and History of Regional Trading Arrangements This sketch of trade regimes in the past half-century surveys only those accords that cover a substantial number of sectors in the economy and grant tariff preferences beyond most-favored nation (MFN) or General System of Preferences (GSP) standards for goods. At the recent pace of change, it is sure to be out of date soon after it is printed.1 Table A1.1 ranks the majority of blocs covered in this appendix on a few relevant characteristics. As can be seen from this table, some of the largest trade blocs are those that have been proposed but not yet implemented. GATT and WTO: The Most Inclusive of All Trading Arrangements Membership: 129 nations plus the European Union; 32 other govern- ments have applied for accession Population (1994 estimates): 3,557 million (64 percent of world’s) Output (1994): $23,682 billion (93 percent of world’s at market exchange rates); $25,973 billion (82 percent of world’s at purchasing power parity [PPP] rates) Foreign trade (exports plus imports in 1994): $7,908.9 billion, of which 91 percent was intrabloc 1. This appendix, mainly drafted by Alan Kackmeister, draws heavily on WTO (1995), IMF (1994), and a number of other histories. For a history of pre-1945 trade arrangements, see Machlup (1977). 246 Institute for International Economics | http://www.iie.com Table A1.1 Existing and proposed multilateral trade blocs by GDP, 1994 Institute forInternationalEconomics |http://www.iie.com GDP at market GDP at purchasing Block Existing exchange rates Population power parity rates Number of type bloca (billions of dollars) (millions) (billions of dollars) countries 1. -

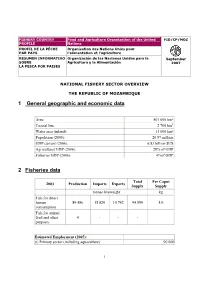

1 General Geographic and Economic Data 2 Fisheries Data

FISHERY COUNTRY Food and Agriculture Organization of the United FID/CP/MOZ PROFILE Nations PROFIL DE LA PÊCHE Organisation des Nations Unies pour PAR PAYS l'alimentation et l'agriculture RESUMEN INFORMATIVO Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la September SOBRE Agricultura y la Alimentación 2007 LA PESCA POR PAISES NATIONAL FISHERY SECTOR OVERVIEW THE REPUBLIC OF MOZAMBIQUE 1 General geographic and economic data Area: 801 600 km² Coastal line 2 700 km2 Water area (inland): 13 000 km² Population (2006): 20.97 million GDP current (2006): 6.83 billion $US Agricultural GDP (2006): 28% of GDP Fisheries GDP (2006): 4%of GDP 2 Fisheries data . Total Per Caput 2003 Production Imports Exports Supply Supply tonnes liveweight kg Fish for direct human 89 486 15 820 10 742 94 559 5.0 consumption Fish for animal feed and other 4 - - - purposes Estimated Employment (2005): (i) Primary sector (including aquaculture): 90 000 1 (ii) Secondary sector: Gross value of fisheries output (2005): 80 million $US Trade (2006): Value of fisheries imports: 31 776 000 $US Value of fisheries exports: 96 638 000 $US 3 Fishery areas and main resources Mozambique is endowed with fairly rich fisheries resources, both marine and freshwater. The marine waters cover an area of about 100 000 km2 with an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 200 nautical miles while inland waters cover an area of about 13 000 km2. The marine fisheries resources are mostly located in the two major shelves, the Sofala Bank in the center and the Delagoa bight in the south. The main fishing areas are located at the Sofala Bank, Inhambane, Vilankulos, Chiluane and Beira.