Kalkara and Birzebbuga in Early Postcards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Property Transactions: April 2021

11 May 2021 | 1100 hrs | 087/2021 The number of fi nal deeds of sale relating to residential property during April 2021 amounted to 1,130, an increase of 540 deeds when compared to those registered a year earlier. In April 2021, 1,430 promise of sale agreements relating to residential property were registered, an increase of 1,161 agreements over the same period last year. Residential Property Transactions: April 2021 Cut-off date: Final Deeds of Sale 4 May 2021 In April 2021, the number of fi nal deeds of sale relating to residential property amounted to 1,130, an increase of 540 deeds when compared to those registered a year earlier (Table 1). The value of these deeds totalled €228.4 million, 91.6 per cent higher than the corresponding value recorded in April 2020 (Table 2). With regard to the region the property is situated in, the highest numbers of fi nal deeds of sale were recorded in the two regions of Mellieħa and St Paul’s Bay, and Ħaż-Żabbar, Xgħajra, Żejtun, Birżebbuġa, Marsaskala and Marsaxlokk, at 150 and 143 respectively. The lowest numbers of deeds were noted in the region of Cottonera, and the region of Mdina, Ħad-Dingli, Rabat, Mtarfa and Mġarr. In these regions, 13 and 32 deeds respectively were recorded (Table 3). Chart 1. Registered fi nal deeds of sale - monthly QXPEHURIUJLVWHUHGILQDOGHHGV - )0$0- - $621' - )0$0- - $621' - )0$ SHULRG Compiled by: Price Statistics Unit Contact us: National Statistics Offi ce, Lascaris, Valletta VLT 2000 1 T. +356 25997219, E. [email protected] https://twitter.com/NSOMALTA/ https://www.facebook.com/nsomalta/ Promise of Sale Agreements In April 2021, 1,430 promise of sale agreements relating to residential property were registered, an increase of 1,161 agreements over the same period last year (Table 4). -

Introduction – Grand Harbour Marina

introduction – grand harbour marina Grand Harbour Marina offers a stunning base in historic Vittoriosa, Today, the harbour is just as sought-after by some of the finest yachts Malta, at the very heart of the Mediterranean. The marina lies on in the world. Superbly serviced, well sheltered and with spectacular the east coast of Malta within one of the largest natural harbours in views of the historic three cities and the capital, Grand Harbour is the world. It is favourably sheltered with deep water and immediate a perfect location in the middle of the Mediterranean. access to the waterfront, restaurants, bars and casino. With berths for yachts up to 100m (325ft) in length, the marina offers The site of the marina has an illustrious past. It was originally used all the world-class facilities you would expect from a company with by the Knights of St John, who arrived in Malta in 1530 after being the maritime heritage of Camper & Nicholsons. exiled by the Ottomans from their home in Rhodes. The Galley’s The waters around the island are perfect for a wide range of activities, Creek, as it was then known, was used by the Knights as a safe including yacht cruising and racing, water-skiing, scuba diving and haven for their fleet of galleons. sports-fishing. Ashore, amid an environment of outstanding natural In the 1800s this same harbour was re-named Dockyard Creek by the beauty, Malta offers a cosmopolitan selection of first-class hotels, British Colonial Government and was subsequently used as the home restaurants, bars and spas, as well as sports pursuits such as port of the British Mediterranean Fleet. -

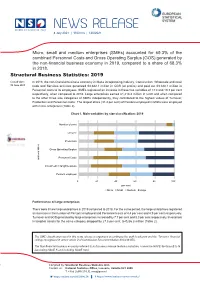

Structural Business Statistics: 2019

8 July 2021 | 1100 hrs | 120/2021 Micro, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) accounted for 69.3% of the combined Personnel Costs and Gross Operating Surplus (GOS) generated by the non-financial business economy in 2019, compared to a share of 68.3% in 2018. Structural Business Statistics: 2019 Cut-off date: In 2019, the non-financial business economy in Malta incorporating Industry, Construction, Wholesale and retail 30 June 2021 trade and Services activities generated €3,882.1 million in GOS (or profits) and paid out €3,328.1 million in Personnel costs to its employees. SMEs registered an increase in these two variables of 13.0 and 10.3 per cent respectively, when compared to 2018. Large enterprises earned €1,218.3 million in GOS and when compared to the other three size categories of SMEs independently, they contributed to the highest values of Turnover, Production and Personnel costs. The largest share (31.4 per cent) of Persons employed in Malta were employed with micro enterprises (Table 2). Chart 1. Main variables by size classification: 2019 Number of units Turnover Production Gross Operating Surplus Personnel Costs main variables Investment in tangible assets Persons employed 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% per cent Micro Small Medium Large Performance of large enterprises There were 8 new large enterprises in 2019 compared to 2018. For the same period, the large enterprises registered an increase in the number of Persons employed and Personnel costs of 4.4 per cent and 4.9 per cent respectively. Turnover and GOS generated by large enterprises increased by 7.7 per cent and 8.3 per cent respectively. -

Malta & Gozo Directions

DIRECTIONS Malta & Gozo Up-to-date DIRECTIONS Inspired IDEAS User-friendly MAPS A ROUGH GUIDES SERIES Malta & Gozo DIRECTIONS WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Victor Paul Borg NEW YORK • LONDON • DELHI www.roughguides.com 2 Tips for reading this e-book Your e-book Reader has many options for viewing and navigating through an e-book. Explore the dropdown menus and toolbar at the top and the status bar at the bottom of the display window to familiarize yourself with these. The following guidelines are provided to assist users who are not familiar with PDF files. For a complete user guide, see the Help menu of your Reader. • You can read the pages in this e-book one at a time, or as two pages facing each other, as in a regular book. To select how you’d like to view the pages, click on the View menu on the top panel and choose the Single Page, Continuous, Facing or Continuous – Facing option. • You can scroll through the pages or use the arrows at the top or bottom of the display window to turn pages. You can also type a page number into the status bar at the bottom and be taken directly there. Or else use the arrows or the PageUp and PageDown keys on your keyboard. • You can view thumbnail images of all the pages by clicking on the Thumbnail tab on the left. Clicking on the thumbnail of a particular page will take you there. • You can use the Zoom In and Zoom Out tools (magnifying glass) to magnify or reduce the print size: click on the tool, then enclose what you want to magnify or reduce in a rectangle. -

IGT (Wines) Production Protocols Regulations, 2007

B 2251 Suppliment tal-Gazzetta tal-Gvern ta’ Malta, Nru. 18,094, 28 ta’ Gunju, 2007 Taqsima B ________________________________________________________________________________ L.N. 167 of 2007 WINE ACT (CAP. 436) I{T Wines Production Protocols Regulations, 2007 IN exercise of the powers conferred by articles 12(1) and 27 of the Wine Act and regulation 11(5) of the Denomination of Origin and of Geographic Indications Regulations, the Minister for Rural Affairs and the Environment has made the following regulations:- 1. (1) The title of these regulations is the I.{.T. Wines Citation and Production Protocols Regulations, 2007. commencement. (2) These regulations shall be deemed to have come into force on the 1st May, 2007. 2. In these regulations, unless already defined in the Act, the Interpretation. following words and phrases shall have the following meanings: "the Act" means the Wine Act; Cap. 436. "the Minister" means the Minister responsible for agriculture; "the Unit" means the office responsible for viticulture and oenology. 3. The Unit is hereby designated as the competent office for Designation of enforcing these regulations and for the certification of the prescribed competency. I.{.T. wines . 4. (1) Certification shall be awarded by the Unit following an Certification of official request, made in writing, from the wine producer concerned wines. and after the Unit has carried out the necessary technical and administrative checks to verify that the wines produced conform to the relevant protocol. (2) Wines shall only be certified as "MALTESE ISLANDS" I.{.T. wines if the protocol in Schedule I is fully respected. B 2252 Schedule I Production Protocol of the "Maltese Islands" I.{.T. -

Census of Population and Housing 2011

CENSUS OF POPULATION AND HOUSING 2011 Preliminary Report National Statistics Office, Malta, 2012 Published by the National Statistics Office Lascaris Valletta Malta Tel.: (+356) 25 99 70 00 Fax: (+356) 25 99 72 05 e-mail: [email protected] website: http://www.nso.gov.mt CIP Data Census of Population and Housing 2011, Preliminary Report. - Valletta: National Statistics Office, 2012 xxx, 53p. ISBN: 978-99957-29-35-6 For further information, please contact: Research and Methodology Unit National Statistics Office Lascaris Valletta VLT 2000 Malta Tel: (+356) 25 99 78 29 Our publications are available from: The Data Shop National Statistics Office Lascaris Valletta VLT 2000 Tel.: (+356) 25 99 72 19 Fax: (+356) 25 99 72 05 Printed at the Government Printing Press CONTENTS Page FOREWORD v 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Legal background ix 1.2 Participation in the Census ix 1.3 Confidentiality ix 1.4 Information Campaign ix 1.5 Operation x 1.5.1 Project Management x 1.5.2 Operations Centre x 1.5.3 The Census Questionnaire x 1.5.4 Operations x 1.5.5 Briefing Sessions xi 1.5.6 Enumeration Areas xi 1.5.7 Field Work xii 1.5.8 Keying-In of Data xiii 1.6 Post-Enumeration xiii 1.6.1 Follow-up exercise xiii 1.6.2 Final Report xiii 1.6.3 Accuracy of Preliminary Findings xiii 2. COMMENTARY 2.1 Population growth along the years xvii 2.2 Geographical distribution xviii 2.3 Population by living quarters xx 2.4 Population density xx 2.5 Gender distribution xxi 2.6 Age distribution xxii 2.7 Distribution by nationality xxiii 3. -

5 Major Projectes Presentation

Locally Funded Major Projects April 2011 List of Projects Currently being undertaken: Smart City Malta US Embassy Junction Triq San Anard – Ta’ Barkat, Xaghjra Qui-Si-Sana, Sliema Valletta Pedestrianisation Smart City Malta Smart City Road Construction Smart City Malta The Concept: This project is being proposed in conjunction with the construction of the dual carriageway two lane road which from Fgura will lead to SCM. It consists of the resurfacing of a number of roads in the Cottonera Area bordering the SCM development. Resurfacing will be localised and according to need, whilst it is being envisaged that the length of roads to be resurfaced is as follows: Triq Santa Liberata, Kalkara: 850m Triq il-Missjoni Taljana & Triq il-Marina, Kalkara: 1800m Triq San Dwardu from Bieb is-Sultan to Triq Santa Liberata, Bormla: 285m Triq San Dwardu from Triq Santa Liberata to Pjazza G Gulia, Bormla: 750m Triq il-Labour and Triq il-Mina ta’ Hompesch, Zabbar: 625m Works in two phases will have a cost of : €1 million Commencement of works : July 2011 Smart City Malta Triq Santa Liberata – as existing Typical Details for Triq Santa Liberata US Embassy Junction Ta’ Qali Existing Junction Proposed Junction US Embassy Junction Ta’ Qali The Concept: This project is being proposed in conjunction the access to the US Embassy building in Ta’ Qali. The works incorporate a new storm water system, the upgrading of existing storm water culverts and also the upgrading of the existing roundabout junction. The new designs include works as follows: Roundabout Junction Construction: Euro 325, 346 Storm Water System: Euro 134, 648 Commencement: April 2011 Completion: July 2011 Triq San Anard Xghajra Ta’ Barkat STP Triq San Anard Xghajra Ta’ Barkat STP The Concept: This project is being proposed in conjunction with the construction of the new Sewage Treatment Plant at Ta’ Barkat. -

Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MALTA • SICILY • ITALY Led by Dr

Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MALTA • SICILY • ITALY Led by Dr. Carl Rasmussen MAY 11-22, 2021 organized by Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome / May 11-22, 2021 Malta Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MAY 11-22, 2021 Fri 14 May Ferry to POZZALLO (SICILY) - SYRACUSE – Ferry to REGGIO CALABRIA Early check out, pick up our box breakfasts, meet the English-speaking assistant at our hotel and transfer to the port of Malta. 06:30am Take a ferry VR-100 from Malta to Pozzallo (Sicily) 08:15am Drive to Syracuse (where Paul stayed for three days, Acts 28.12). Meet our guide and visit the archeological park of Syracuse. Drive to Messina (approx. 165km) and take the ferry to Reggio Calabria on the Italian mainland (= Rhegium; Acts 28:13, where Paul stopped). Meet our guide and visit the Museum of Magna Grecia. Check-in to our hotel in Reggio Calabria. Dr. Carl and Mary Rasmussen Dinner at our hotel and overnight. Greetings! Mary and I are excited to invite you to join our handcrafted adult “study” trip entitled Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Sat 15 May PAESTUM - to POMPEII Martyrdom in Rome. We begin our tour on Malta where we will explore the Breakfast and checkout. Drive to Paestum (435km). Visit the archeological bays where the shipwreck of Paul may have occurred as well as the Island of area and the museum of Paestum. Paestum was a major ancient Greek city Malta. Mark Gatt, who discovered an anchor that may have been jettisoned on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea in Magna Graecia (southern Italy). -

Accommodation Recommendations Concetta Host House Julesy's Bnb

Accommodation Recommendations Please note: Conference location: Villa Bighi in Kalkara For Cultural event on 11th January 2018 meeting points are in Barrakka Gardens, Valletta and Cospicua Waterfront. Transport to and from Valletta and Cospicua will be provided. For more details please refer to the conference agenda. Location: Birgu Concetta Host House Distance from Villa Bighi: 5 mins by car Price: € Make your Reservation .... Location: Cospicua Julesy's BnB Distance from Villa Bighi: 5 mins by car Price: €€€ Make your Reservation .... Location: Cospicua Casa Birmula Hotel Distance from Villa Bighi: 5 mins by car Price: €€ Make your Reservation .... 1 Location: Valletta Grand Hotel Excelsior***** Distance from Villa Bighi: 35 mins by car Price: €€ Make your Reservation .... Location: Valletta Osborne Hotel*** Distance from Villa Bighi: 35 mins by car Price: € Make your Reservation .... Location: Valletta Hotel Castille*** Distance from Villa Bighi: 35 mins by car Price: € Make your Reservation .... 2 Please book your accommodation directly with the logging provider. Location: Attard Corinthia Palace Hotel & Spa***** Distance from Villa Bighi: 40mins by car Price: €€ Make your Reservation .... Location: Sliema The Victoria Hotel**** Distance from Villa Bighi: 27 mins by car Price: € Make your Reservation .... Location: Saint Julians Hotel Juliani Distance from Villa Bighi: 27 mins by car price: € Make your Reservation .... 3 Please book your accommodation directly with the logging provider. Recommended Hotel Locations Other Information Public Transport: Bus Routes & Schedules Public Ferry from Sliema to Valletta: Schedule Public Ferry from Valletta to Cospicua: Schedule Boarding at 9.10am Conference Location Kalkara Built in 1675 by a knight of the Order of St. -

Annual Report 2017 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 CONTENTS 3 4 9 CEO Water Water Report Resources Quality 14 20 32 Compliance Network Corporate Infrastructure Services Directorate 38 45 48 Strategic Human Unaudited Information Resources Financial Directorate Statement 2017 ANNUAL REPORT CEO REPORT CEO Report 2017 was a busy year for the Water Services quality across Malta. Secondly, RO plants will be Corporation, during which it worked hard to become upgraded to further improve energy efficiency and more efficient without compromising the high quality production capacity. Furthermore, a new RO plant service we offer our customers. will be commissioned in Gozo. This RO will ensure self-sufficiency in water production for the whole During a year, in which the Corporation celebrated island of Gozo. The potable water supply network to its 25th anniversary, it proudly inaugurated the North remote areas near Siġġiewi, Qrendi and Haż-Żebbuġ Wastewater Treatment Polishing Plant in Mellieħa. will be extended. Moreover, ground water galleries This is allowing farmers in the Northern region to will also be upgraded to prevent saline intrusion. benefit from highly polished water, also known as The project also includes the extension of the sewer ‘New Water’. network to remote areas that are currently not WSC also had the opportunity to establish a number connected to the network. Areas with performance of key performance indicator dashboards, produced issues will also be addressed. inhouse, to ensure guaranteed improvement. These Having only been recently appointed to lead the dashboards allow the Corporation to be more Water Services Corporation, I fully recognize that the efficient, both in terms of performance as well as privileges of running Malta’s water company come customer service. -

Migration, Surnames and Marriage in the Maltese Island of Gozo Around 1900

Journal of Maltese History, 2011/2 Migration, surnames and marriage in the Maltese island of Gozo around 1900. H.V.Wyatt Visiting Lecturer in the School of Philosophy, University of Leeds. Abstract The marriage records in the Public Registry in Gozo have been used to count the. frequency of surnames. Children with poliomyelitis and their controls from the same villages have been traced to their great grand-parents. These records have been used to trace migration to and from the larger island of Malta and the extent of consanguinity in each village. ______________________________________________________ Dr. Wyatt has held research and teaching posts in England, the United States, and the West Bank. He has taught and researched for 2 years in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh and for 4 years in Malta. He was previously Honorary Research Fellow in Public Health Medicine at Leeds University. Acknowledgements: I am very grateful to the Peel Medical Research Trust and the Royal Society for travel grants, to all the doctors, parish priests and other clergy who helped me, but especially to Professors H.M.Gilles and A. Scicluna-Spiteri. 35 Journal of Maltese History, 2011/2 Introduction To the north-west of Malta is the smaller island of Gozo (Fig 1), with an area of 67 square kilometres and about one tenth the population of Malta. In November 1942 poliovirus was introduced to the islands from Egypt and more than 420 children were paralysed. There were later, but smaller epidemics, until mass immunisation with the Sabin vaccine ensured that there have been no cases since 1964. -

Summer Schedules

ISLA/VALLETTA 1 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 1 - Schedule Times Route 1 - Schedule Times Route 1 - Schedule Times 05:30-09:30 20 minutes 05:30-22:30 30 minutes 05:30-22:30 30 minutes 09:31-11:29 30 minutes 11:30-16:30 20 minutes 16:31-23:00 30 minutes BIRGU VENDA/VALLETTA 2 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 2 - Schedule Times Route 2 - Schedule Times Route 2- Schedule Times 05:15-20:25 20 minutes 05:30:00-22:45 30 minutes 05:30:00-22:45Isla/Birgu/Bormla/Valletta30 minutes 20:26-22:45 60 minutes KALKARA/VALLETTA 3 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 3 - Schedule Times Route 3 - Schedule Times Route 3 - Schedule Times 05:30 - 23:00 30 minutes 05:30 - 23:00 30 minutes 05:30Isla/Birgu/Bormla/Valletta - 23:00 30 minutes BIRGU CENTRE/VALLETTA 4 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 4 - Schedule Times Route 4 - Schedule Times Route 4 - Schedule Times 05:30:00 - 20:30 30 minutes 05:30-20:00 30 minutes 05:30-20:00 30 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 60 minutes 20:01-23:00 60 minutes 20:01-23:00 60 minutes BAHAR IC-CAGHAQ/VALLETTA 13 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 13 - Schedule Times Route 13 - Schedule Times Route 13 - Schedule Times 05:05 - 20:30 10 minutes 05:05 - 20:30 10 minutes 05:05 - 20:30 10 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 15 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 15 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 15 minutes PEMBROKE/VALLETTA 14 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 14 - Schedule Times Route 14 - Schedule Times Route 14 - Schedule Times 05:25 - 20:35 20 minutes 05:25 - 20:35 20 minutes 05:25 - 20:35 20 minutes 20:36 -22:48 30 minutes 20:36 -22:48 30 minutes