Dakar, Senegal Casenote

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dangerous Vagabonds”: Resistance to Slave

“DANGEROUS VAGABONDS”: RESISTANCE TO SLAVE EMANCIPATION AND THE COLONY OF SENEGAL by Robin Aspasia Hardy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Robin Aspasia Hardy 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION PAGE For my dear parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Methodology .............................................................................. 4 Sources ..................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter Overview .................................................................................................... 20 2. SENEGAL ON THE FRINGE OF EMPIRE.......................................................... 23 Senegal, Early French Presence, and Slavery ......................................................... 24 The Role of Slavery in the French Conquest of Senegal’s Interior ......................... 39 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 51 3. RACE, RESISTANCE, AND PUISSANCE ........................................................... 54 Sex, Trade and Race in Senegal ............................................................................... 55 Slave Emancipation and the Perpetuation of a Mixed-Race -

Practical Information – Dakar

Practical information – Dakar Dakar Dakar, capital of Senegal and one of the chief seaports on the western African coast. It is located midway between the mouths of the Gambia and Sénégal rivers on the south-eastern side of the Cape Verde Peninsula, close to Africa’s most westerly point. Dakar’s harbour is one of the best in Western Africa, being protected by the limestone cliffs of the cape and by a system of breakwaters. The city’s name comes from dakhar, a Wolof name for the tamarind tree, as well as the name of a coastal Lebu village that was located south of what is now the first pier. King Fahd Conference Centre The meetings will be held at the King Fahd Conference Centre which also houses the King Fahd Hotel. Those of you staying at the King Fahd Hotel can move from the lobby to the Conference Centre without leaving the building. The Yaas Hotel is the closest recommended hotel to the venue and is only 5 minutes away. Attached is a map of the King Fahd Conference Centre for reference. The Airport The main airport in Dakar is the Blaise Diagne International (DSS). Blaise Diagne International Airport is located on the east of the downtown of Dakar near the town of Diass. It is linked to the city via taxis, busses and shuttles. Travel to and from the Airport The Government of Senegal has kindly offered shuttle busses between the airport and the hotels recommended to the Secretariat. Please send Leah Krogsund ([email protected]) your arrival and departure dates and times should you require the use of these services. -

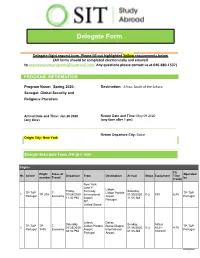

Delegate Form

Delegate Form Delegate flight request form. Please fill out highlighted Yellow requirements below (All forms should be completed electronically and emailed to [email protected]. Any questions please contact us at 646-880-1537) PROGRAM INFORMATION Program Name: Spring 2020: Destination: Africa, South of the Sahara Senegal: Global Security and Religious Pluralism Arrival Date and Time: Jan 26 2020 Return Date and Time: May 09 2020 (any time) (any time after 1 pm) Return Departure City: Dakar Origin City: New York Sample Schedule From JFK @ $ 1800 Flights Flt Flight Class of Operated Nr. Airline Departure From Destination Arrival Stops Equipment Time number Travel by (Total) New York, John F. Lisbon, Friday, Kennedy Saturday, TP-TAP T- Lisbon Portela TP-TAP 1 TP 208 01/24/2020 International 01/25/2020 0 () 339 6:35 Portugal Economy Airport, Portugal 11:30 PM Airport, 11:05 AM Portugal NY, United States Lisbon, Dakar, Saturday, Sunday, Airbus TP-TAP TP T- Lisbon Portela Blaise Diagne TP-TAP 2 01/25/2020 01/26/2020 0 () A321- 4:15 Portugal 1485 Economy Airport, International Portugal 08:50 PM 01:05 AM 100/200 Portugal Airport, 1 Delegate Form Dakar, Paris, Saturday, Sunday, AF-Air Q- Blaise Diagne Charles De Boeing 777- AF-Air 3 AF 719 05/09/2020 05/10/2020 0 () 5:30 France Economy International Gaulle Airport, 300 France 11:05 PM 06:35 AM Airport, France New York, John F. Paris, Sunday, Kennedy Sunday, AF-Air Q- Paris Orly Boeing 777- AF-Air 4 AF 032 05/10/2020 International 05/10/2020 0 () 8:25 France Economy Airport, 200 France 02:15 PM Airport, 04:40 PM France NY, United States Nonrefundable Changeable for a fee 2 bags permitted with AF, Zero bag with TP Please see below for Personal Details. -

2011 Minerals Yearbook

2011 Minerals Yearbook THE GAMBIA, GUINEA-BISSAU, AND SENEGAL U.S. Department of the Interior September 2013 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUSTRIES OF THE GAMBIA, GUINEA-BISSAU, AND SENEGAL By Omayra Bermúdez-Lugo THE GAMBIA Industrial Minerals Mining in The Gambia was limited to the production of Phosphate Rock.—On February 22, Plains Creek Phosphate industrial minerals and did not play a significant role in the Corp. of Canada announced the results of a technical study country’s economy. In 2011, the Government did not publish [National Instrument 43–101 (NI 43–101)] regarding the mineral production data, and information on the production of economic potential of the Farim phosphate project. Measured clay, ilmenite, laterite, silica sand, and zircon was not available and indicated resources of phosphate rock ore were reported to make reliable estimates of output. Although the Government to be 84 million metric tons (Mt) at an average grade of 29.9% reported production of ilmenite and rutile in 2009 and 2010 P2O5 and a cutoff thickness of 1.5 meters (m). Inferred resources and that of rutile concentrate and zircon in 2007, there were no were estimated to be 44 Mt at an average grade of 29.6% P2O5 known ongoing titanium mineral projects in the country. The and a cutoff thickness of 1.5 m. Plains Creek owned a 50.1% country did not produce petroleum and depended upon imports interest in the Farim deposit and had the right to acquire the to meet its domestic energy requirements. remaining 49.9% interest in the project from GB Minerals AG of Switzerland. -

The French Model of Assimilation and Direct Rule - Faidherbe and Senegal –

The French Model of Assimilation and Direct Rule - Faidherbe and Senegal – Key terms: Assimilation Association Direct rule Mission Dakar–Djibouti Direct Rule Direct rule is a system whereby the colonies were governed by European officials at the top position, then Natives were at the bottom. The Germans and French preferred this system of administration in their colonies. Reasons: This system enabled them to be harsh and use force to the African without any compromise, they used the direct rule in order to force African to produce raw materials and provide cheap labor The colonial powers did not like the use of chiefs because they saw them as backward and African people could not even know how to lead themselves in order to meet the colonial interests It was used to provide employment to the French and Germans, hence lowering unemployment rates in the home country Impacts of direct rule It undermined pre-existing African traditional rulers replacing them with others It managed to suppress African resistances since these colonies had enough white military forces to safeguard their interests This was done through the use of harsh and brutal means to make Africans meet the colonial demands. Assimilation (one ideological basis of French colonial policy in the 19th and 20th centuries) In contrast with British imperial policy, the French taught their subjects that, by adopting French language and culture, they could eventually become French and eventually turned them into black Frenchmen. The famous 'Four Communes' in Senegal were seen as proof of this. Here Africans were granted all the rights of French citizens. -

The Historical Aspects of Pan-Africanism a Personal Chronicle

RAYFORD W.LOGAN Professor of History, Howard University The Historical Aspects of Pan-Africanism A Personal Chronicle The history of Pan-Africanism as a movement to encourage mutual assistance and understanding among the peoples of Africa and of African descent goes back to the beginning of the twentieth century, but it was only after World War I-that calamitous folly of the so-called superior races-that the movement as a whole began to have the ultimate aim of some form of self-government for African peoples. The credit for con- ceiving the idea of the Pan-African Conference that met in London in July, 1900, belongs to H. Sylvester Williams, a young West Indian lawyer. Among his aims were to bring peoples of African descent throughout the world into closer touch with one another and to establish friendlier rela- tions between the Caucasian and African races. That he did not envision self-government or independence in Africa is evident from another of his stated objectives, namely, "to start a movement looking forward to the securing to all African races living in civilized countries their full rights and to promote their business interests." (my italics) It was William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, as Chairman of the Con- ference's Committee on Address to the Nations of the World, who trans- formed Williams's limited conception of Pan-Africanism into a movement for self-government or independence for African peoples. He urged : "Let the British Nation, the first modern champion of Negro freedom, hasten to . give, as soon as practicable, the rights of responsible government to the Black Colonies of Africa and the West Indies." Du Bois said noth- ing about the Spanish and Portuguese colonies, and he did not explicitly demand "responsible government" for the German and French colonies. -

Airports and Air Navigation Services Providers

Case Study: Senegal Background There are 20 aerodromes in Senegal. Among them, one receives scheduled international traffic, and four are major regional airports. The international airport is Dakar-Léopold Sédar Senghor International Airport, which is also Senegal’s busiest airport. The four most important regional airports are Saint-Louis Airport in the Northeast, Cap Skirring Airport in the Southeast, Ziguinchor airport in the Casamance region, and Tambacounda Airport in the East. Since the suspension of Air Sénégal International in 2009, traffic at these regional airports has decreased substantially. The Directorate of Civil Aviation (DAC, Direction de l’Aviation Civile) used to be a structure of the Ministry of Transport. Its main role was to implement Senegal’s air transport policy and to supervise the provision of airport and air navigation services. These services were delivered by the Agency for Air Navigation Safety in Africa & Madagascar (ASECNA, Agence pour la sécurité de la navigation aérienne en Afrique et à Madagascar). ASECNA was created in 1959 as a multinational public corporation. It comprises 18 Member States from francophone Africa. ASECNA used to operate the Dakar-Léopold Sédar Senghor International Airport and other regional airports in Senegal (under the article 10 of the Convention of Dakar of 25 October 1974). More specifically, airports used to be managed by the Senegal National Aeronautic Activities Agency (AAANS, Administration des activités aéronautiques nationales du Sénégal), whose Chief Executive was appointed by ASECNA’s General Director on the advice of the Senegal’s Minister of Civil Aviation. ASECNA still provides air navigation services through six flight information regions (Antananarivo, Brazzaville, Dakar Oceanic and Terrestrial, Niamey, and N’Djamena). -

Africandevelopmentbank

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP Public Disclosure Authorized BANK GROUP’S COUNTRY STRATEGY PAPER FOR SENEGAL, 2016-2020 Public Disclosure Authorized July 2016 Translated Document TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................. i EXECUTIVE SUMMMARY .............................................................................................................. iii I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 1 II. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ...................................................................................................... 1 2.1 Political, Economic and Social Context ...................................................................................... 1 2.2 Strategic Options .......................................................................................................................... 6 2.3 Aid Coordination Developments and Bank Positioning ............................................................ 10 III. BANK GROUP STRATEGY FOR THE 2016-20210 PERIOD ............................................. 11 3.1 Rationale for Bank Intervention ................................................................................................. 12 3.2 Bank’s Pillars ............................................................................................................................ 13 3.3 Expected Outcomes and Targets ............................................................................................... -

Blaise Diagne

Blaise Diagne Extrait du Au Senegal http://www.au-senegal.com Blaise Diagne - Français - Découvrir le Sénégal, pays de la teranga - Histoire - Date de mise en ligne : mercredi 22 aot 2007 Description : Voir aussi • Histoire du Sénégal Au Senegal • Les Institutions du Sénégal Copyright © Au Senegal Page 1/5 Blaise Diagne Blaise Diagne & Cela vous dit-il quelque chose ? & Oui, bien sûr ! Blaise Diagne a été le premier député africain au sein de l'Assemblée nationale française. Certes, mais c'était en 1914. Qui est Blaise Diagne aujourd'hui ? & Le maire d'un charmant village du Vaucluse : Lourmarin & et petit-fils de son homonyme ! Nous l'avons rencontré. Blaise Diagne avec écharpe tricolore lorsqu'il allait siéger pour la première fois (1914) à la Chambre des députés. Photo : Centre de recherche et de documentation du Sénégal. Fils de Niokhor, un Sérère de Gorée qui était cuisinier et marin, et Gnagna Preira, une mandjaque originaire de Guinée-Bissau, Blaise Adolphe Diagne, naît à Gorée le 13 octobre 1872. Il s'appelait Gaiaye M'Baye Diagne. C'est à l'Ecole des Frères de Ploërmel de Gorée où son père adoptif, Adolphe Crespin, l'inscrivit, qu'il fut baptisé "Blaise". Plus tard, il l'envoya poursuivre ses études dans le sud de la France, à Aix-en-Provence. Il termine ses études à Saint-Louis, au Nord du Sénégal et en 1891, est reçu au concours des douanes coloniales. C'est ainsi qu'après le Dahomey, le Congo, Madagascar, La Réunion, (où il est accepté par le Grand Orient ce qui fait de lui l'un des premiers Noirs francs-maçons), il réside en Guyane. -

Constructing Dakar: Cultural Theory and Colonial Power Relations in French African Urban Development

CONSTRUCTING DAKAR: CULTURAL THEORY AND COLONIAL POWER RELATIONS IN FRENCH AFRICAN URBAN DEVELOPMENT by Dustin Alan Harris B.A. Honours History, University of British Columbia, 2008 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department Of History © Dustin Alan Harris 2011 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2011 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Dustin Alan Harris Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Constructing Dakar: Cultural Theory and Colonial Power Relations in French African Urban Development Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Mary-Ellen Kelm Associate Professor, Department of History Simon Fraser University ___________________________________________ Dr. Roxanne Panchasi Senior Supervisor Associate Professor, Department of History Simon Fraser University ___________________________________________ Dr. Nicolas Kenny Supervisor Assistant Professor, Department of History Simon Fraser University ___________________________________________ Dr. Hazel Hahn External Examiner Associate Professor, Department of History Seattle University Date Defended/Approved: January 26 2011 Note (Don’t forget to delete this note before printing): The Approval page must be only one page long. This is because it MUST be page “ii”, while the Abstract page MUST begin on page “iii”. To accommodate longer titles, longer examining committee lists, or any other feature that demands more space, you have a variety of choices. Consider reducing the font size (10 pt is acceptable), changing the font (see templates Appendix 2, for font choices), using a table to create two columns for examiners, reducing spacing for signatures, indentation and tab spacing. -

Program Itinerary and Prepare for Their Next Day!

DAY ONE: Travel from origin to Senegal West Africa DAY TWO: Arrive in Senegal – Participants are met by PASI staff at the Blaise Diagne International Airport in Senegal and then travel by private bus to Dakar. Participants then arrive at their lodging accommodation, get settled, and attend an orientation where they are introduced to our dedicated accommodations provider and staff before eating a Senegalese dinner. After dinner, students have their first nightly meeting to discuss the program itinerary and prepare for their next day! DAY THREE: History, Culture and City Tour – Participants begin the day with a safety orientation with hired security to discuss safety precautions in Senegal. They then meet up with their Field Coordinator and together take a tour around the city, learning the history of Senegal through visiting several historical sites (e.g. N’Gor Island, Museum of Black Civilization Cheikh Anta Diop University and more). Participants are later greeted by Prometra International staff for a service orientation presentation. At the end of the day, students will reflect on their historical and cultural experiences through journaling and conversations facilitated by PASI staff as well as participating college professors. DAY FOUR: Goree Island - The day of history begins with a 20 minute ferry ride from Dakar to one of Senegal’s top destinations and the most visited sites in Senegal, Goree Island. Of all the places to visit and to learn about Senegal's history, Goree Island is one of the best locations. Participants will visit the “THE DOOR OF NO RETURN” which is a major departure point in the African Slave Trade and is the last place African slaves saw before being shipped across the ocean to the Americas. -

Notam Summary May 01, 2020

AGENCE POUR LA SÉCURITÉ DE LA NAVIGATION AÉRIENNE EN AFRIQUE ET A MADAGASCAR NOTAM SUMMARY Phone : +(221) 77.519.79.01 +(221) 33.957.49.37 SERIES A and B Fax : +(221) 33.820.06.00 AFTN : GOOOYNYX MAY 01, 2020 E-mail : [email protected] BUREAU NOTAM INTERNATIONAL DE L’OUEST AFRICAIN Web : https:aim.asecna.aero B.P. 8155 Aéroport International Blaise Diagne Dakar/Diass-SENEGAL BENIN – BURKINA FASO – COTE D’IVOIRE – GUINEE BISSAU – MALI – MAURITANIE – NIGER – SENEGAL – TOGO The Following NOTAM (series A&B) were still valid on May 01st, 2020. NOTAM not included have been cancelled, time expired, or incorporated into ASECNA AIP. SERIE A YEAR 2015: 0579 0580 YEAR 2016: 0391 0695 0796 1150 1200 1211 1322 YEAR 2017: 0465 0659 1301 1406 YEAR 2018: 0052 0582 0583 0630 0631 0817 1273 1629 1639 1645 1910 1937 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 1950 1951 1987 YEAR 2019: 0111 0158 0159 0176 0178 0255 0268 0459 0615 1000 1201 1240 1510 1515 1652 1712 1812 1959 1961 YEAR 2020: 0019 0062 0065 0066 0073 0080 0086 0099 0106 0114 0119 0136 0141 0149 0150 0155 0159 0163 0169 0170 0173 0174 0186 0191 0192 0193 0194 0204 0206 0214 0217 0230 0231 0233 0239 0240 0241 0242 0249 0250 0282 0283 0284 0285 0286 0287 0288 0296 0301 0305 0306 0307 0308 0310 0311 0320 0321 0326 0327 0328 0329 0330 0333 0338 0339 0340 0341 0343 0347 0351 0353 0354 0358 0360 0361 0368 0369 0373 0374 0375 0383 0420 0456 0457 0478 0479 0481 0482 0483 0484 0485 0486 0487 0488 0497 0508 0509 0510 0511 0523 0524 0527 0528 0529 0532 0533 0535 0547 0548 0556 0564 0583 0585 0596 0604 0609 0611 0619