Early African Responses to Colonialism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dangerous Vagabonds”: Resistance to Slave

“DANGEROUS VAGABONDS”: RESISTANCE TO SLAVE EMANCIPATION AND THE COLONY OF SENEGAL by Robin Aspasia Hardy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Robin Aspasia Hardy 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION PAGE For my dear parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Methodology .............................................................................. 4 Sources ..................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter Overview .................................................................................................... 20 2. SENEGAL ON THE FRINGE OF EMPIRE.......................................................... 23 Senegal, Early French Presence, and Slavery ......................................................... 24 The Role of Slavery in the French Conquest of Senegal’s Interior ......................... 39 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 51 3. RACE, RESISTANCE, AND PUISSANCE ........................................................... 54 Sex, Trade and Race in Senegal ............................................................................... 55 Slave Emancipation and the Perpetuation of a Mixed-Race -

Vol. 24 - Benin

Marubeni Research Institute 2016/09/02 Sub -Saharan Report Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the focal regions of Global Challenge 2015. These reports are by Mr. Kenshi Tsunemine, an expatriate employee working in Johannesburg with a view across the region. Vol. 24 - Benin August 10, 2016 Even without knowing where the location of the country of Benin is, many Japanese may remember Zomahoun Rufin, better known as “Zomahon”, as an African who became famous as a “TV personality” on the Japanese television show “Hey Japanese People, This is Strange” for the interesting way he spoke Japanese. “Oh, you say Zomahon is from Benin? And he is now the Benin ambassador to Japan (note 1)?” as many Japanese are and would be surprised to hear. Through him though, many have in some way a feeling for the country, which you may have guessed is the country I am introducing this time, Benin. Table 1: Benin Country Information Benin is located in West Africa bordered by Togo in the west, Burkina Faso in the northwest, Niger in the northeast and Nigeria in the east while facing the Bay of Guinea in the south. The constitutional capital of the country is Porto Novo, however, the political and economic center of the country is found in it largest city Cotonou, which also boasts the country’s only international airport (picture 1). Picture 1: A street with vendors in town near the border with Togo 1 8/10//2016 Benin is only 120 kilometers from east to west, while being 700 kilometers in length from north to south being a narrow, elongated country like Togo which I introduced last time. -

Practical Information – Dakar

Practical information – Dakar Dakar Dakar, capital of Senegal and one of the chief seaports on the western African coast. It is located midway between the mouths of the Gambia and Sénégal rivers on the south-eastern side of the Cape Verde Peninsula, close to Africa’s most westerly point. Dakar’s harbour is one of the best in Western Africa, being protected by the limestone cliffs of the cape and by a system of breakwaters. The city’s name comes from dakhar, a Wolof name for the tamarind tree, as well as the name of a coastal Lebu village that was located south of what is now the first pier. King Fahd Conference Centre The meetings will be held at the King Fahd Conference Centre which also houses the King Fahd Hotel. Those of you staying at the King Fahd Hotel can move from the lobby to the Conference Centre without leaving the building. The Yaas Hotel is the closest recommended hotel to the venue and is only 5 minutes away. Attached is a map of the King Fahd Conference Centre for reference. The Airport The main airport in Dakar is the Blaise Diagne International (DSS). Blaise Diagne International Airport is located on the east of the downtown of Dakar near the town of Diass. It is linked to the city via taxis, busses and shuttles. Travel to and from the Airport The Government of Senegal has kindly offered shuttle busses between the airport and the hotels recommended to the Secretariat. Please send Leah Krogsund ([email protected]) your arrival and departure dates and times should you require the use of these services. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. “A SACRED TRUST OF CIVILIZATION:” THE B MANDATES UNDER BRITAIN, FRANCE, AND THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS PERMANENT MANDATES COMMISSION, 1919-1939 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School, The Ohio State University By Paul J. Hibbeln, B.A, M A The Ohio State University 2002 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Carole Fink, Advisor Professor John Rothney C c u o a lg . -

Taxes, Institutions, and Governance: Evidence from Colonial Nigeria

Taxes, Institutions and Local Governance: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Colonial Nigeria Daniel Berger September 7, 2009 Abstract Can local colonial institutions continue to affect people's lives nearly 50 years after decolo- nization? Can meaningful differences in local institutions persist within a single set of national incentives? The literature on colonial legacies has largely focused on cross country comparisons between former French and British colonies, large-n cross sectional analysis using instrumental variables, or on case studies. I focus on the within-country governance effects of local insti- tutions to avoid the problems of endogeneity, missing variables, and unobserved heterogeneity common in the institutions literature. I show that different colonial tax institutions within Nigeria implemented by the British for reasons exogenous to local conditions led to different present day quality of governance. People living in areas where the colonial tax system required more bureaucratic capacity are much happier with their government, and receive more compe- tent government services, than people living in nearby areas where colonialism did not build bureaucratic capacity. Author's Note: I would like to thank David Laitin, Adam Przeworski, Shanker Satyanath and David Stasavage for their invaluable advice, as well as all the participants in the NYU predissertation seminar. All errors, of course, remain my own. Do local institutions matter? Can diverse local institutions persist within a single country or will they be driven to convergence? Do decisions about local government structure made by colonial governments a century ago matter today? This paper addresses these issues by looking at local institutions and local public goods provision in Nigeria. -

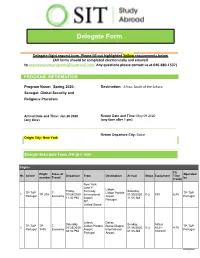

Delegate Form

Delegate Form Delegate flight request form. Please fill out highlighted Yellow requirements below (All forms should be completed electronically and emailed to [email protected]. Any questions please contact us at 646-880-1537) PROGRAM INFORMATION Program Name: Spring 2020: Destination: Africa, South of the Sahara Senegal: Global Security and Religious Pluralism Arrival Date and Time: Jan 26 2020 Return Date and Time: May 09 2020 (any time) (any time after 1 pm) Return Departure City: Dakar Origin City: New York Sample Schedule From JFK @ $ 1800 Flights Flt Flight Class of Operated Nr. Airline Departure From Destination Arrival Stops Equipment Time number Travel by (Total) New York, John F. Lisbon, Friday, Kennedy Saturday, TP-TAP T- Lisbon Portela TP-TAP 1 TP 208 01/24/2020 International 01/25/2020 0 () 339 6:35 Portugal Economy Airport, Portugal 11:30 PM Airport, 11:05 AM Portugal NY, United States Lisbon, Dakar, Saturday, Sunday, Airbus TP-TAP TP T- Lisbon Portela Blaise Diagne TP-TAP 2 01/25/2020 01/26/2020 0 () A321- 4:15 Portugal 1485 Economy Airport, International Portugal 08:50 PM 01:05 AM 100/200 Portugal Airport, 1 Delegate Form Dakar, Paris, Saturday, Sunday, AF-Air Q- Blaise Diagne Charles De Boeing 777- AF-Air 3 AF 719 05/09/2020 05/10/2020 0 () 5:30 France Economy International Gaulle Airport, 300 France 11:05 PM 06:35 AM Airport, France New York, John F. Paris, Sunday, Kennedy Sunday, AF-Air Q- Paris Orly Boeing 777- AF-Air 4 AF 032 05/10/2020 International 05/10/2020 0 () 8:25 France Economy Airport, 200 France 02:15 PM Airport, 04:40 PM France NY, United States Nonrefundable Changeable for a fee 2 bags permitted with AF, Zero bag with TP Please see below for Personal Details. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

0 Further Reading

0 Further reading General The best general introduction to the whole period is: Thomson, D., Europe since Napoleon (Penguin, 1966). There are also a number of good series available such as the Fontana History of Europe and Longman 's A General History of Europe. The relevant volumes in these series are as follows: Rude, G., Revolutionary Europe, 1783-1815 (Fontana, 1964). Droz, J., Europe between Revolutions, 1815-1848 (Fontana, 1967). Grenville, J.A.S., Europe Reshaped, 1848-1878 (Fontana, 1976). Stone, N., Europe Transformed, 1878-1919 (Fontana, 1983). Wiskemann, E., Europe of the Dictators, 1919-1945 (Fontana, 1966). Ford, F.L., Europe, 1780-1830 (Longman, 1967). Hearder, H., Europe in the Nineteenth Century, 1830-1880 (Longman, 1966). Roberts, J., Europe, 1880-1945 (Longman, 1967). For more specialist subjects there are various contributions by expert authorities included in: The New Cambridge Modern History, vols. IX-XII (Cambridge, 1957). Cipolla, C.M. (ed.), Fontana Economic History of Europe (Fontana, 1963). Other useful books of a general nature include: Hinsley, F.H., Power and the Pursuit of Peace (Cambridge University Press, 1963). Kennedy, P., Strategy and Diplomacy 1870-1945 (Allen & Unwin, 1983). Seaman, L.C.B., From Vienna to Versailles (Methuen, 1955). Seton-Watson, H., Nations and States (Methuen, 1977). Books of documentary extracts include: Brooks, S., Nineteenth Century Europe (Macmillan, 1983). Brown, R. and Daniels, C., Twentieth Century Europe (Macmillan, 1981). Welch, D., Modern European History, 1871-1975 (Heinemann, 1994). The Longman Seminar Studies in History series provides excellent introductions to debates and docu mentary extracts on a wide variety of subjects. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Recalling Vietnam

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Recalling Vietnam: Queering Temporality and Imperial Intimacies in Contemporary U.S. and Franco-Vietnamese Cultural Productions A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Southeast Asian Studies by Justin Quang Nguyên Phan December 2018 Thesis Committee: Dr. Mariam Beevi Lam, Chairperson Dr. Jodi Kim Dr. Sarita See Copyright by Justin Quang Nguyên Phan 2018 The Thesis of Justin Quang Nguyên Phan is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My deepest gratitude to Mariam Beevi Lam who continues to challenge me to embrace interdisciplinarity and for graciously and patiently meeting with me time and time again to navigate the wonders of the university; to Jodi Kim, for providing sustained and incisive comments on my ideas and for always reminding me to not put the ‘cart before the horse’; and to Sarita See for creating shelters for critical engagement wherever we go since our meeting in her Race, Culture, Labor seminar years ago. Many thanks as well to Crystal Mun-Hye Baik, David Biggs, Evyn Lê Espiritu, Dylan Rodríguez, and Christina Schwenkel for commenting on earlier iterations of my work. While this was indeed a product of many conversations with mentors, friends, and family, any shortcomings in the pages to come are respectfully mine. To the administrative staff—Trina Elerts, Crystal Meza, Iselda Salgado as well as Ryan Mariano, Diana Marroquin, and Kristine Specht—for working with me throughout the transitions to ensure that I fulfill everything necessary for this degree. To Amina Mama, Wendy Ho, and Naomi Ambriz who continue to inspire me to examine the intersections of colonialism, race, class, gender, and sexuality within a transnational perspective. -

2011 Minerals Yearbook

2011 Minerals Yearbook THE GAMBIA, GUINEA-BISSAU, AND SENEGAL U.S. Department of the Interior September 2013 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUSTRIES OF THE GAMBIA, GUINEA-BISSAU, AND SENEGAL By Omayra Bermúdez-Lugo THE GAMBIA Industrial Minerals Mining in The Gambia was limited to the production of Phosphate Rock.—On February 22, Plains Creek Phosphate industrial minerals and did not play a significant role in the Corp. of Canada announced the results of a technical study country’s economy. In 2011, the Government did not publish [National Instrument 43–101 (NI 43–101)] regarding the mineral production data, and information on the production of economic potential of the Farim phosphate project. Measured clay, ilmenite, laterite, silica sand, and zircon was not available and indicated resources of phosphate rock ore were reported to make reliable estimates of output. Although the Government to be 84 million metric tons (Mt) at an average grade of 29.9% reported production of ilmenite and rutile in 2009 and 2010 P2O5 and a cutoff thickness of 1.5 meters (m). Inferred resources and that of rutile concentrate and zircon in 2007, there were no were estimated to be 44 Mt at an average grade of 29.6% P2O5 known ongoing titanium mineral projects in the country. The and a cutoff thickness of 1.5 m. Plains Creek owned a 50.1% country did not produce petroleum and depended upon imports interest in the Farim deposit and had the right to acquire the to meet its domestic energy requirements. remaining 49.9% interest in the project from GB Minerals AG of Switzerland. -

The Black Hole of Empire

Th e Black Hole of Empire Th e Black Hole of Empire History of a Global Practice of Power Partha Chatterjee Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2012 by Princeton University Press Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chatterjee, Partha, 1947- Th e black hole of empire : history of a global practice of power / Partha Chatterjee. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-15200-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-691-15201-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Bengal (India)—Colonization—History—18th century. 2. Black Hole Incident, Calcutta, India, 1756. 3. East India Company—History—18th century. 4. Imperialism—History. 5. Europe—Colonies—History. I. Title. DS465.C53 2011 954'.14029—dc23 2011028355 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Th is book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Pro Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the amazing surgeons and physicians who have kept me alive and working This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface xi Chapter One Outrage in Calcutta 1 Th e Travels of a Monument—Old Fort William—A New Nawab—Th e Fall -

1-101. Africa. Amer. Nat., 57

125 BIBLIOGRAPHY AFZELIUS, K., 1925. Einige neue Senecionen von Kenia und von Mt. Aberdare. Svensk bot. Tidskr. 19: 419-422. Uppsala. ALLEN, G. M., 1939. A Check List of African Mammals. Bull. Mus. Compo Zool. Harv., 83. ALLUAUD, Ch. & ]EANNEL, R, 1915. Le Mont Kenya en Afrique Orientale Anglaise. Rev. Gen. Sci., 25: 639-644. Paris. ARNELL, S., 1956. Hepaticae collected by O. Hedberg et al. on the East African Mountains. Ark. j. Bot. ,Serie 2. 3, nr. 16. AUTHUR, ]. W., 1921. Mount Kenya. Geogr. j., 58: 9-25. AUTHUR, ]. W., 1923. A Sixth Attempt on Mount Kenya. Geogr. j., 62: 205-209. AUTHUR, ]. W., 1936. Radiation and anthocyanin pigments. In DUGGAR, B.M. Biological Effects of Radiation, 2: 1109-1150. ASDELL, S. A., 1946. Patterns of Mammalian Reproduction. New York. ASTLEY MABERLEY, C. T., 1960. Animals in East Africa. Cape Town. BERGHEN, VAN DEN, C., 1953. Quelques hepatiques recoltees par O. Hedberg sur les Montagnes de l' Afrique Orientale. Svensk. bot. Tidskr. 47, 2. Uppsala. BERGSTROM, E., 1955. British Ruwenzori Expedition, 1952. Glaciological Observations, Preliminary Report. J. Glaciol., 2, No. 17: 469-476. BOUGHEY, A. S., 1955. The nomenclature of the vegetation zones on the Mountains of Tropical Africa. Webbia, XI. BRAESTRUP, F. W., 1941. A Study of the Arctic Fox in Greenland. Medd. Grenland, 131: 1-101. BROOKS, C. E. P., 1949. Climate through the Ages. London. BRUCE, E. A., 1934. The Giant Lobelias of East Africa. Kew Bull. 61-88, 274. CAGNOLO, FR. C., 1933. The Akikuyu, Nyeri, Kenya. CARCASSON, R. H., 1964. A preliminary survey of the zoogeography of African Butterflies.