Understanding Life Science Partnership Structures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Santaris Pharma A/S Advances a Second Drug from Its

Santaris Pharma A/S advances a second drug from its cardiometabolic program, SPC4955, inhibiting apoB, into Phase 1 clinical trials for the treatment of high cholesterol Phase 1 clinical study to assess safety and tolerability of SPC4955, a drug inhibiting synthesis of apolipoprotein B (apoB), a major protein component involved in the formation of LDL-C or “bad” cholesterol High cholesterol is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and according to the World Health Organization, it is estimated to cause 18% of strokes and 56% of heart disease globally In preclinical studies, SPC4955 potently and dose-dependently reduced apoB levels resulting in significant and durable reductions in plasma levels of LDL-C and triglycerides Developed using Santaris Pharma A/S Locked Nucleic Acid Drug Platform, SPC4955 is the second to advance into Phase 1 clinical trials from the company’s multi-faceted cardiometabolic program aimed at helping patients achieve target LDL-C levels Hoersholm, Denmark/San Diego, California, May 11, 2011 — Santaris Pharma A/S, a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company focused on the research and development of mRNA and microRNA targeted therapies, today announced that it has advanced a second drug from its cardiometabolic program, SPC4955 into Phase 1 clinical trials, for the treatment of high cholesterol. Developed using Santaris Pharma A/S proprietary Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Drug Platform, SPC4955 is a mRNA-targeted drug candidate that inhibits apolipoprotein B (apoB), a major protein component involved in the formation of low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) or “bad” cholesterol. Cholesterol is an essential component of all cells and several important hormones, but cholesterol levels that are out of balance or too high overall lead to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques that cause cardiovascular diseases such as heart attacks or strokes. -

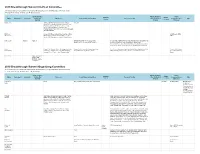

2019 Breakthrough Summit Co-Host Committee 2019 Breakthrough

2019 Breakthrough Summit Co-Host Committee All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless otherwise noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution Stock and Other Patents, Royalties, Travel, Speakers' Expert Name Employment Leadership Ownership Honoraria Consulting or Advisory Role Research Funding Other Intellectual Accommodations, Other Bureau Testimony Interests Property Expenses Dae Ho Lee Abbvie, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Boehringer ST Cube Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceutical, CJ Healthcare, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, Samyang, ST Cube, Takeda Ekaphop Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol- AstraZeneca, MSD, Sirachainan Myers Squibb, Diethelm Keller Logistics, LF Asia, Pfizer Merck, MSD, Mundipharma, Roche, Sanofi/Aventis Lillian L. Siu Agios (I) Agios (I) AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Loxo, Merck, Amgen (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Bayer (Inst), MorphoSys, Roche, Symphony Evolution Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Genentech/Roche (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), MedImmune (Inst), Merck (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Symphony Evolution (Inst) Virote Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Lilly, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Sriuranpong Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Lilly, MSD Oncology, Eisai, MSD Oncology, Novartis, Roche MSD Oncology, -

Advances in Oligonucleotide Drug Delivery

REVIEWS Advances in oligonucleotide drug delivery Thomas C. Roberts 1,2 ✉ , Robert Langer 3 and Matthew J. A. Wood 1,2 ✉ Abstract | Oligonucleotides can be used to modulate gene expression via a range of processes including RNAi, target degradation by RNase H-mediated cleavage, splicing modulation, non-coding RNA inhibition, gene activation and programmed gene editing. As such, these molecules have potential therapeutic applications for myriad indications, with several oligonucleotide drugs recently gaining approval. However, despite recent technological advances, achieving efficient oligonucleotide delivery, particularly to extrahepatic tissues, remains a major translational limitation. Here, we provide an overview of oligonucleotide-based drug platforms, focusing on key approaches — including chemical modification, bioconjugation and the use of nanocarriers — which aim to address the delivery challenge. Oligonucleotides are nucleic acid polymers with the In addition to their ability to recognize specific tar- potential to treat or manage a wide range of diseases. get sequences via complementary base pairing, nucleic Although the majority of oligonucleotide therapeutics acids can also interact with proteins through the for- have focused on gene silencing, other strategies are being mation of three-dimensional secondary structures — a pursued, including splice modulation and gene activa- property that is also being exploited therapeutically. For tion, expanding the range of possible targets beyond example, nucleic acid aptamers are structured -

Next Generation Immuno-Oncology Targeting Hot and Cold Tumors

Next generation immuno-oncology targeting hot and cold tumors March 2017 iTeos – General Disclaimer Company Presentation “This presentation has been prepared by iTeos and is furnished to you by iTeos on a confidential basis and solely for your information. This presentation contains forward-looking statements, including (without limitation) statements concerning the progress and expectations of our (pre-)clinical pipeline and the financials of the company. When used in this presentation, the words “anticipate,” “believe,” “can,” “could,” “estimate,” “expect,” “intend,” “is designed to,” “may,” “might,” “will,” “plan,” “potential,” “possible,” “predict,” “objective,” “should,” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward- looking statements. Forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors which might cause the actual results, financial condition, performance or achievements of iTeos, or industry results, to be materially different from any future results, financial conditions, performance or achievements expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. All statements contained herein speak only as of the release date of this document. iTeos expressly disclaims any obligation to update any statement in this document to reflect any change or future development with respect thereto, any future results, or any change in events, conditions and/or circumstances on which any such statement is based, unless specifically required by law or regulation. Neither iTeos nor any of its officers, -

IGNYTE-ESO: a Master Protocol to Assess Safety and Activity of Letetresgene Autoleucel (Lete-Cel; GSK3377794) Victoria L

Sandra P. D’Angelo1, Jonathan Noujaim2, Fiona Thistlethwaite3, Albiruni R. Abdul Razak4, Silvia Stacchiotti5, Warren Chow6, John B.A.G. Haanen7, Anna Chalmers8, Steven I. Robinson9, Brian A. Van Tine10, Kristen N. Ganjoo11, Melissa L. Johnson12, 13 13 13 13 13 14 15 IGNYTE-ESO: a master protocol to assess safety and activity of letetresgene autoleucel (lete-cel; GSK3377794) Victoria L. Chiou , Thomas Faitg , Mary Woessner , Laura Pearce , Aiman Shalabi , Jean-Yves Blay , George D. Demetri 1Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; 2Institut D’Hématologie-Oncologie, Hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont, Montreal, QC, Canada; 3The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom; 4Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and in HLA-A*02+ patients with synovial sarcoma or myxoid/round cell liposarcoma (Substudies 1 and 2) Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada; 5Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, Italy; 6City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, CA, United States; 7Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Ziekenhuis, Amsterdam, Netherlands; 8Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA; 9Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA; 10Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA; 11Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, CA, USA; 12Sarah Cannon Research Institute, Nashville, TN, USA; 13GlaxoSmithKline, Philadelphia, PA, USA; Poster No. TPS11582 14Centre Léon Bérard, Lyon, France; 15Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Ludwig Center at Harvard, Boston, MA, USA Background Study design Study phases Unmet need IGNYTE-ESO (NCT03967223) is a master protocol that enables evaluation of multiple cell therapies Figure 3 displays the patient journey for both substudies, which includes leukapheresis for lete-cel manufacture, lymphodepletion chemotherapy, lete-cel infusion, and follow-up. -

Antiviral Research 111 (2014) 53–59

Antiviral Research 111 (2014) 53–59 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Antiviral Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/antiviral Long-term safety and efficacy of microRNA-targeted therapy in chronic hepatitis C patients Meike H. van der Ree a, Adriaan J. van der Meer b, Joep de Bruijne a, Raoel Maan b, Andre van Vliet c, Tania M. Welzel d, Stefan Zeuzem d, Eric J. Lawitz e, Maribel Rodriguez-Torres f, Viera Kupcova g, ⇑ Alcija Wiercinska-Drapalo h, Michael R. Hodges i, Harry L.A. Janssen b,j, Hendrik W. Reesink a, a Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands b Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands c PRA International, Zuidlaren, The Netherlands d J.W. Goethe University Hospital, Frankfurt, Germany e The Texas Liver Institute, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX, USA f Fundacion de Investigacion, San Juan, Porto Rico g Department of Internal Medicine, Derer’s Hospital, University Hospital Bratislava, Slovakia h Medical University of Warsaw, Warsaw Hospital for Infectious Diseases, Warsaw, Poland i Santaris Pharma A/S, San Diego, USA j Liver Clinic, Toronto Western & General Hospital, University Health Network, Toronto, Canada article info abstract Article history: Background and aims: MicroRNA-122 (miR-122) is an important host factor for hepatitis C virus (HCV) Received 6 June 2014 and promotes HCV RNA accumulation. Decreased intra-hepatic levels of miR-122 were observed in Revised 28 July 2014 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, suggesting a potential role of miR-122 in the development of Accepted 29 August 2014 HCC. -

Genomic Landscape of Cell-Free DNA in Patients with Colorectal Cancer

Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on December 1, 2017; DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-1009 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. Genomic landscape of cell-free DNA in patients with colorectal cancer John H. Strickler1, Jonathan M. Loree2, Leanne G. Ahronian3, Aparna R. Parikh3, Donna Niedzwiecki1, Allan Andresson Lima Pereira2, Matthew Mckinney1, W. Michael Korn4,5, Chloe E. Atreya4, Kimberly C. Banks6, Rebecca J. Nagy6, Funda Meric-Bernstam2, Richard B. Lanman6, AmirAli Talasaz6, Igor F. Tsigelny7,8, Ryan B. Corcoran3 #, Scott Kopetz2 # 1Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA; 2University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA; 3Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center and Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; 4Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA; Caris Life Sciences, Phoenix, AZ, USA; 6Guardant Health, Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA; 7University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA; 8CureMatch Inc., San Diego, CA, USA. #To whom correspondence should be addressed: Dr. Ryan B. Corcoran Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, 149 13th St., 7th floor Boston, MA 02129 Phone: 617-726-8599 Fax: 617-724-9648 Email: [email protected] Dr. Scott Kopetz University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Unit 426 Houston, TX 77030 Phone: 713-792-2828 Fax: 713-563-2957 Email: [email protected] 1 Downloaded from cancerdiscovery.aacrjournals.org on September 28, 2021. © 2017 American Association for Cancer Research. Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on December 1, 2017; DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-1009 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. -

Feasibility and First Reports of the MATCH-R Repeated Biopsy Trial At

www.nature.com/npjprecisiononcology ARTICLE OPEN Feasibility and first reports of the MATCH-R repeated biopsy trial at Gustave Roussy Gonzalo Recondo 1, Linda Mahjoubi2, Aline Maillard3, Yohann Loriot1,4, Ludovic Bigot1, Francesco Facchinetti1, Rastislav Bahleda2, Anas Gazzah2, Antoine Hollebecque2, Laura Mezquita4, David Planchard1,4, Charles Naltet4, Pernelle Lavaud4, Ludovic Lacroix1,5,6, Catherine Richon5, Aurelie Abou Lovergne7, Thierry De Baere8, Lambros Tselikas8, Olivier Deas9, Claudio Nicotra2, Maud Ngo-Camus2, Rosa L. Frias1, Eric Solary10, Eric Angevin2, Alexander Eggermont4, Ken A. Olaussen1, Gilles Vassal7, Stefan Michiels 3, ✉ Fabrice Andre 1,4, Jean-Yves Scoazec5,6, Christophe Massard1,2, Jean-Charles Soria1,4, Benjamin Besse1,4 and Luc Friboulet 1 Unravelling the biological processes driving tumour resistance is necessary to support the development of innovative treatment strategies. We report the design and feasibility of the MATCH-R prospective trial led by Gustave Roussy with the primary objective of characterizing the molecular mechanisms of resistance to cancer treatments. The primary clinical endpoints consist of analyzing the type and frequency of molecular alterations in resistant tumours and compare these to samples prior to treatment. Patients experiencing disease progression after an initial partial response or stable disease for at least 24 weeks underwent a tumour biopsy guided by CT or ultrasound. Molecular profiling of tumours was performed using whole exome sequencing, RNA sequencing and panel sequencing. At data cut-off for feasibility analysis, out of 333 inclusions, tumour biopsies were obtained in 303 cases (91%). From these biopsies, 278 (83%) had sufficient quality for analysis by high-throughput next generation sequencing (NGS). All 278 samples underwent targeted NGS, 215 (70.9%) RNA sequencing and 222 (73.2%) whole 1234567890():,; exome sequencing. -

Compugen Ltd. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter and Translation of Registrant's Name Into English) ______

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F ☐ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2017 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☐ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 DATE OF EVENT REQUIRING THIS SHELL COMPANY REPORT __________ COMMISSION FILE NO. 000-30902 ____________________________________________________ Compugen Ltd. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter and translation of registrant's name into English) ___________________________________________________________________ Israel (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) Azrieli Center, 26 Harokmim Street, Building D, Holon 5885849 Israel (Address of principal executive offices) ________________________________________________ Ari Krashin, Chief Financial Officer Phone: +972-3-765-8585, Fax: +972-3-765-8555 Azrieli Center, 26 Harokmim Street, Building D, Holon 5885849 Israel (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) ________________________________________________ Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Ordinary shares, par value NIS 0.01 per share The NASDAQ Stock Market LLC (The NASDAQ Global Market) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: None Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer's classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report: 51,293,070 Ordinary Shares Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

Steady Course Or Changing Tides? 2015 Trial Starts 2016 Clinical Trials Roundup – Steady Course Or Changing Tides?

2016 Clinical Trials Roundup Steady course or changing tides? 2015 Trial Starts 2016 Clinical Trials Roundup – Steady course or changing tides? Welcome to this year’s roundup where we’ll review clinical trials that initiated in 2015 to elucidate any ongoing, or new, trends within the world of pharma R&D. Here we’ll provide a high-level overview of trial activity, focused on the six major therapeutic areas (TAs) of autoimmune/inflammation, cardiovascular, CNS, infectious disease, metabolic/endocrinology, and oncology, with metrics by TA, trial phase, and disease. We’ll then zoom in on the most active industry sponsors, including a closer look at how they may (or may not be) maximizing their assets. Now, let’s take a look at the new clinical research from 2015, and see how the course of pharma R&D fared. Doro Shin, MPH Principal Analyst, Infectious & Genitourinary Diseases Manager, Thought Leadership Program 2 April 2016 © Informa UK Ltd 2016 (Unauthorized photocopying prohibited.) Rounding up the 2015 debuts Similar to years past, this annual roundup will hone in on unapproved drug3 clinical research, which comprised Approximately 4,900 Phase I-III trials started in 2015 2,769 of trials starting in 2015 (57%). Involvement across the six TAs.1 Industry sponsors2 were involved from the industry is increased as 77% of trials initiated in the majority of these trials (2934 of 4895 trials, in 2015 with an unapproved drug is linked to an 60%), particularly in autoimmune research (487 of industry sponsor (2143 of 2769 trials). Again, 668 trials, 73%). Oncology had the lowest rate and autoimmune has the largest industry participation (383 just over half of cancer trials included an industry of 424 trials, 90%) while oncology has the lowest (750 sponsor (1110 of 2080 trials). -

Brevpapir, Kun Dansk Adresse

Santaris Pharma A/S announce agreement with GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) to develop RNA-targeted medicines. Hørsholm, Denmark/San Diego, California, January 10, 2014 — Santaris Pharma A/S has announced today that they have signed an agreement with GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), whereby, pursuant to an option right, GSK gains access to Santaris’ Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) technology to develop RNA-targeted medicines. Under the terms of the agreement, GSK can obtain rights to utilize Santaris Pharma’s proprietary Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Drug Platform to research, develop and commercialize LNA-medicines targeted against up to three targets. Financials details on the deal were not disclosed. “We are delighted to do this new deal with GSK” said Dr. Henrik Ørum, Chief Scientific Officer and VP business development of Santaris Pharma. “This is the sixth partner deal we have concluded in the past 12 months with pharmaceutical and biotech companies, so it has really been a spectacular year for Santaris Pharma”. About Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Drug Platform The LNA Drug Platform and Drug Discovery Engine developed by Santaris Pharma A/S combines the company’s proprietary LNA chemistry with its highly specialized and targeted drug development capabilities to rapidly deliver LNA-based drug candidates against both mRNA and microRNA, thus enabling scientists to develop drug candidates against diseases that are difficult, or impossible, to target with contemporary drug platforms such as antibodies and small molecules. The LNA Drug Platform overcomes the limitations of earlier antisense and siRNA technologies through a unique combination of small size and very high affinity that allows this new class of drugs candidates to potently and specifically inhibit RNA targets in many different tissues without the need for complex delivery vehicles. -

Santaris Pharma A/S Announces an Expanded Worldwide Strategic

Santaris Pharma A/S announces expanded worldwide strategic alliance with Pfizer Inc. directed to development of RNA-targeted medicines Pfizer to make payment of $14 million for access to Santaris Pharma A/S Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Drug Platform to develop RNA-targeted drugs Santaris Pharma A/S eligible to receive milestone payments of up to $600 million as well as royalties on sales of products that may develop for up to 10 new RNA targets selected by Pfizer The newly expanded alliance builds on the original collaboration formed in January 2009 between Santaris Pharma A/S and Wyeth, which was acquired by Pfizer Inc. Agreement demonstrates that the Santaris Pharma A/S LNA Drug Platform is a technology-of- choice for developing RNA-targeted medicines for unmet medical needs Hoersholm, Denmark/San Diego, California, January 4, 2011 — Santaris Pharma A/S, a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company focused on the research and development of mRNA and microRNA targeted therapies, and Pfizer Inc. (NYSE:PFE), today announced that the companies have expanded their collaboration directed to the development and commercialization of RNA-targeted medicines using Santaris Pharma A/S Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Drug Platform. Under the terms of the expanded agreement, Pfizer will make a payment of $14 million for access to Santaris Pharma A/S LNA technology for the development of RNA-targeted drugs. Santaris Pharma A/S is eligible to receive milestone payments of up to $600 million as well as royalties on sales of products that may be developed for up to 10 new RNA targets selected by Pfizer.