Brief on Bill C-78: an Act to Amend the Divorce Act, the Family Orders And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Divorce Act Changes Explained

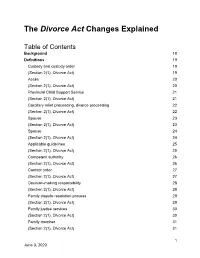

The Divorce Act Changes Explained Table of Contents Background 18 Definitions 19 Custody and custody order 19 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 19 Accès 20 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 20 Provincial Child Support Service 21 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 21 Corollary relief proceeding, divorce proceeding 22 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 22 Spouse 23 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 23 Spouse 24 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 24 Applicable guidelines 25 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 25 Competent authority 26 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 26 Contact order 27 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 27 Decision-making responsibility 28 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 28 Family dispute resolution process 29 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 29 Family justice services 30 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 30 Family member 31 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 31 1 June 3, 2020 Family violence 32 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 32 Legal adviser 35 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 35 Order assignee 36 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 36 Parenting order 37 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 37 Parenting time 38 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 38 Relocation 39 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 39 Jurisdiction 40 Two proceedings commenced on different days 40 (Sections 3(2), 4(2), 5(2) Divorce Act) 40 Two proceedings commenced on same day 43 (Sections 3(3), 4(3), 5(3) Divorce Act) 43 Transfer of proceeding if parenting order applied for 47 (Section 6(1) and (2) Divorce Act) 47 Jurisdiction – application for contact order 49 (Section 6.1(1), Divorce Act) 49 Jurisdiction — no pending variation proceeding 50 (Section 6.1(2), Divorce Act) -

Untying the Knot: an Analysis of the English Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Court Records, 1858-1866 Danaya C

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2004 Untying the Knot: An Analysis of the English Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Court Records, 1858-1866 Danaya C. Wright University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Common Law Commons, Family Law Commons, and the Women Commons Recommended Citation Danaya C. Wright, Untying the Knot: An Analysis of the English Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Court Records, 1858-1866, 38 U. Rich. L. Rev. 903 (2004), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/205 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNTYING THE KNOT: AN ANALYSIS OF THE ENGLISH DIVORCE AND MATRIMONIAL CAUSES COURT RECORDS, 1858-1866 Danaya C. Wright * I. INTRODUCTION Historians of Anglo-American family law consider 1857 as a turning point in the development of modern family law and the first big step in the breakdown of coverture' and the recognition of women's legal rights.2 In 1857, The United Kingdom Parlia- * Associate Professor of Law, University of Florida, Levin College of Law. This arti- cle is a continuation of my research into nineteenth-century English family law reform. My research at the Public Record Office was made possible by generous grants from the University of Florida, Levin College of Law. -

Child Custody Modification Under the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act: a Statute to End the Tug-Of-War?

Washington University Law Review Volume 67 Issue 3 Symposium on the State Action Doctrine of Shelley v. Kraemer 1989 Child Custody Modification Under the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act: A Statute to End the Tug-of-War? C. Gail Vasterling Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation C. Gail Vasterling, Child Custody Modification Under the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act: A Statute to End the Tug-of-War?, 67 WASH. U. L. Q. 923 (1989). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol67/iss3/15 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHILD CUSTODY MODIFICATION UNDER THE UNIFORM MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE ACT: A STATUTE TO END THE TUG-OF-WAR? Each year approximately one million American children experience the trauma of their parents' divorces.1 The resulting child custody deci- sions involve familial complications and difficulties requiring judicial dis- cretion.' The amount of discretion trial court judges currently exercise, however, often yields unpredictable and poorly reasoned decisions. Fre- quently, the trial court judge's decision motivates the losing parent to relitigate.3 In an effort to ensure greater stability after the initial custody decision and to dissuade further litigation, the drafters of the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act (UMDA)4 provided a variety of procedural and substantive limitations on a judge's ability to grant changes in custody.5 This Note evaluates the UMDA's custody modification provisions and explores their application by the courts. -

Equalizing the Cost of Divorce Under the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act: Maintenance Awards in Illinois Jane Rutherford Assist

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 23 Issue 3 Spring 1992 Illinois Judicial Conference Article 5 Symposium 1992 Equalizing the Cost of Divorce Under the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act: Maintenance Awards in Illinois Jane Rutherford Assist. Prof., DePaul University College of Law Barbara Tishler Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Litigation Commons Recommended Citation Jane Rutherford, & Barbara Tishler, Equalizing the Cost of Divorce Under the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act: Maintenance Awards in Illinois, 23 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 459 (1992). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol23/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Equalizing the Cost of Divorce Under the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act: Maintenance Awards in Illinois Jane Rutherford* Barbara Tishler** "The first of earthly blessings, independence." Edward Gibbon1 "To be poor and independent is very nearly an impossibility." William Cobbett2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................... 460 II. FOSTERING INDEPENDENCE ........................ 465 A. The Duty to Own Property ..................... 471 B. The Duty to Be Employed ...................... 475 1. Full-time Homemakers ..................... 475 2. Unequal Earners ........................... 485 3. Equal Earners .............................. 493 III. R ELIANCE .......................................... 495 IV. CONTRIBUTION/UNJUST ENRICHMENT ............. 497 V. REASONABLE NEEDS ............................... 501 VI. STANDARD OF LIVING ............................. 503 VII. EQUALITY .......................................... 504 A. Disparate Income As a Measure of Need ........ 505 B. Disparate Income As a Method of Allocating Gains and Losses .............................. -

Special Series on the Federal Dimensions of Reforming the Supreme

SPECIAL SERIES ON THE FEDERAL DIMENSIONS OF REFORMING THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA The Jurisprudence of ʺCanadaʹs Fundamental Valuesʺ and Appointment to the Supreme Court of Canada F. C. DeCoste Faculty of Law, University of Alberta Institute of Intergovernmental Relations School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University SC Working Paper 2010 - 02 DeCoste, F.C., The Jurisprudence of "Canada's Fundamental Values"… Page 1 Judged by the norms of liberal democratic governance, our system of appointing judges to the Supreme Court of Canada is a constitutional embarrassment. This much must, by now, be beyond dispute. Since the Court's founding in 1875, s. 101 of the Constitution Act 1867 has been taken by successive federal executives to be a grant of unfettered -- which is to say, rule-less1 and therefore largely lawless -- prime ministerial discretion. In consequence, both the process and the substance of appointment offend in disgracefully equal measure the principles of transparent and accountable government. That this sorry state of constitutional affairs has not in fact fatally compromised the legitimacy of the Court can only, I think, be attributed to the complicity of those who know or ought to know better -- the legal, academic, and press communities especially included -- in the maintenance of civic ignorance among Canadians. But further criticism in these regards is not my remit in this too brief working paper.2 Instead I shall argue that the Court's post-Charter devotion to what it terms "Canada's fundamental values" violates a core constitutional principle of federalism. I shall then argue that this violation not only supports but demands remediation by way of a role for the provinces in the appointment process. -

The Constitution of Canada and the Conflict of Laws

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons PhD Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2001 The onsC titution of Canada and the Conflict of Laws Janet Walker Osgoode Hall Law School of York University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/phd Part of the Conflict of Laws Commons, and the Jurisdiction Commons Recommended Citation Walker, Janet, "The onC stitution of Canada and the Conflict of Laws" (2001). PhD Dissertations. 18. http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/phd/18 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in PhD Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. THE CONSTITUTION OF CANADA AND THE CONFLICT OF LAWS Janet Walker A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Worcester College Trinity Term 2001 The Constitution of Canada and the Conflict of Laws Janet Walker, Worcester College Doctor of Philosophy Thesis, Trinity Term 2001 This thesis explains the constitutional foundations for the conflict of laws in Canada. It locates these constitutional foundations in the text of key constitutional documents and in the history and the traditions of the courts in Canada. It compares the features of the Canadian Constitution that provide the foundation for the conflict of laws with comparable features in the constitutions of other federal and regional systems, particularly of the Constitutions of the United States and of Australia. This comparison highlights the distinctive Canadian approach to judicial authority-one that is the product of an asymmetrical system of government in which the source of political authority is the Constitution Act and in which the source of judicial authority is the continuing local tradition of private law adjudication. -

Adultery As a Bar to Dower

University of Miami Law Review Volume 13 Number 1 Article 7 10-1-1958 Misconduct in the Marital Relation: Adultery as a Bar to Dower Harold A. Turtletaub Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Recommended Citation Harold A. Turtletaub, Misconduct in the Marital Relation: Adultery as a Bar to Dower, 13 U. Miami L. Rev. 83 (1958) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol13/iss1/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS MISCONDUCT IN THE MARITAL RELATION: ADULTERY AS A BAR TO DOWER INTRODUCTION In what is a case of first impression,' a Florida district court recently 2 held that the Statute of Westminster was not a part of the law of Florida. The statute3 enacted in 1285 stated that "If a uqfe willingly leave her hus- band and go away and continuc with her advouterer," (emphasis added) she shall be barred of her dower4 unless her husband should afterward forgive her and take her back. In other vords, the common law doctrine declared that a wife would forfeit her dower if she voluntarily left her husband and committed adultery. It is the purpose of this article to discuss this ancient common law statute and its subsequent treatment by the various states of the Union. -

LESA LIBRARY Neuman Thompson Dunphy Best Blocksom LLP Edmonton, Alberta Calgary, Alberta

62097.00 8th Annual Law & Practice Update Calgary, Alberta Chair Todd Munday Wood & Munday LLP Bonnyville, Alberta Faculty Hon. Judge A.A. Fradsham Pam L. Bell Provincial Court of Alberta Bell and Stock Family Law LLP Calgary, Alberta Calgary, Alberta Roger S. Hofer QC Jonathan F. Griffith LESA LIBRARY Neuman Thompson Dunphy Best Blocksom LLP Edmonton, Alberta Calgary, Alberta Elizabeth Aspinall Nolan B. Johnson Law Society of Alberta Huckvale LLP Calgary, Alberta Lethbridge, Alberta LEGAL EDUCATION SOCIETY OF ALBERTA These materials are produced by the Legal Education Society of Alberta (LESA) as part of its mandate in the field of continuing education. The information in the materials is provided for educational or informational purposes only. The information is not intended to provide legal advice and should not be relied upon in that respect. The material presented may be incorporated into the working knowledge of the reader but its use is predicated upon the professional judgment of the user that the material is correct and is appropriate in the circumstances of a particular use. The information in these materials is believed to be reliable; however, LESA does not guarantee the quality, accuracy, or completeness of the information provided. These materials are provided as a reference point only and should not be relied upon as being inclusive of the law. LESA is not responsible for any direct, indirect, special, incidental or consequential damage or any other damages whatsoever and howsoever caused, arising out of or in connection with the reliance upon the information provided in these materials. This publication may contain reproductions of the Statutes of Alberta and Alberta Regulations, which are reproduced in this publication under license from the Province of Alberta. -

Divorce in Alberta and Prairie Canada, 1905-1930

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1998 Rescinding the vow: Divorce in Alberta and prairie Canada, 1905-1930 Rankin, Allison Rankin, A. (1998). Rescinding the vow: Divorce in Alberta and prairie Canada, 1905-1930 (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/21380 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/26217 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Rescinding the Vow: Divorce in Alberta and Prairie Canada, 1905-1930 Allison Rankin A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE ilEGaEZ OF MASTEK OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA DECEMBER, I998 @ Allison Rankin, 1998 National Library Bibliothique nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington O#awaON K1AW OUawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Blbliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan., distribute or sell reproduire, prster, distriher ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

The. Federal Divorce Act (1968) And

The. Federal Divorce Act (1968) and. the Constitution F. J. E. Jordan * Introduction Throughout the proceedings of the Special Joint Committee of the Senate nd the House of Commons on Divorce which sat from June, 1966 through April of the following year and throughout the debates of the House of Commons and the Senate auring December, 1967 and January, 1968 on Bill C-187, nearly as much attentioni was focussed on questions of legislative jurisdiction in relation to divorce and related matters as was directed to the .substantive changes to be made in reforming the grounds for divorce in Canada. On some of the constitutional issueg," opinions a to legislative competence were nearly unanimous; on others, they were much more divided. In Bill C-187 as finally enacted, a substantial number of these issues were resolved in favour of the federal Parliament's jurisdiction and sections were included in the Divorce Act' dealing with the creation of a federal divorce court, the jurisdiction of provincial courts, questions of domicile and recognition of foreign decrees and matters of corollary relief in divorce proceedings; how- ever, at least two significant issues were left untouched by Parliament because of doubts as to its legislative competence in relation to them: judicial separation and corollary matters and the division of. matri- monial property on dissolution of a marriage. Also omitted from the legislation, without comment, is the matter of annulment of marriage. In result, we have a new federal divorce law - indeed, the first real federal divorce law - which, in going as far as it does to provide a comprehensive coverage of the field of divorce, raises some doubts as to the validity of certain provisions in the Act, while at the same time, in stopping short of the desired coverage, leaves us with an enactment which fails to deal with some important aspects of the termination of marriage otherwise than by death of a spouse. -

"J\(Ot Tmade out Ofj^Evity" Evolution Of'divorce in Early "Pennsylvania

"J\(ot tMade Out ofJ^evity" Evolution of'Divorce in Early "Pennsylvania "X"Y THEREAS>" read ^e preamble of the Commonwealth's % /\/ first substantial divorce code, in its felicitous eighteenth- T Y century phrasing, it is the design of marriage, and the wish of parties entering into that state that it should continue during their joint lives, yet where the one party is under natural or legal incapacities of faithfully discharging the matrimonial vow, or is guilty of acts and deeds inconsistent with the nature thereof, the laws of every well regulated society ought to give relief to the innocent and injured person.1 The Act of September 19, 1785, exemplar among a spate of state statutes passed in the post-war pioneering period in American law and doctrine, formed the basis of all subsequent Pennsylvania di- vorce legislation and had its foundation in the Commonwealth's colonial and Revolutionary experiences and experiments.2 The earliest statutory provision in Pennsylvania pertaining to divorce, a provision nullifying bigamous marriages, appeared in the Duke of York's laws of 1664.3 In the 1665 alterations of the laws divorce from bed and board4 for the crime of adultery was estab- lished: "In cases of Adultery all proceedinges shall bee accordinge to 1 The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania from 1682-1801 (Harrisburg, 1896-1908), XII, 94. 2 George J. Edwards, Jr., Divorce: Its Development in Pennsylvania and the Present Law and Practice Therein (New York, 1930), 3-11. 3 Abraham L. Freedman and Maurice Freedman, Law of Marriage and Divorce in Pennsyl- vania (Philadelphia, 1957), I, 248; Charter to William Penn, and Laws of the Province of Penn- sylvania, passed between the years 1682 and 1700, preceded by Duke of York's Laws in force from the year 1676 to the year 1682 (Harrisburg, 1879), 36. -

1 BILL C-78: an Act to Amend the Divorce Act, the Family Orders and Agreements Enforcement Assistance Act and the Garnishment

BILL C-78: An Act to amend the Divorce Act, the Family Orders and Agreements Enforcement Assistance Act and the Garnishment, Attachment and Pension Diversion Act and to make consequential amendments to another Act Discussion Paper by Luke’s Place Support and Resource Centre, Durham Region, Ontario and National Association of Women and the Law/Association nationale Femmes et Droit* (NAWL/ANFD) October 2018 * Funding for the NAWL Project; “Rebuilding Feminist Law Reform Capacity: Substantive Equality in the Law Making Process” was generously provided by Status of Women Canada. 1 INTRODUCTION Purpose of the discussion paper This joint NAWL (National Association of Women and the Law) and Luke’s Place paper is intended to form the basis for discussion and advocacy on Bill C-78: An Act to amend the Divorce Act, the Family Orders and Agreements Enforcement Assistance Act and the Garnishment, Attachment and Pension Diversion Act and to make consequential amendments to another Act (hereinafter Bill C-78) by women’s equality-seeking and violence against women organizations and advocates across the country.† We hope this discussion paper will be a valuable feminist law reform resource that will be used by a range of organizations and individuals to prepare written and oral testimony on Bill C-78 for Parliamentary and/or Senate Committees and other advocacy, and that it will also be useful for decision-makers involved in the law making process. There are many welcome additions and changes in Bill C-78. Luke’s Place and NAWL support having children and their well-being remain at the centre of the Divorce Act.