UNIVERSITY of MIAMI Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Diel Variation in the Catch of the Shrimp Farfantepenaeus Duorarum (Decapoda, Penaeidae) and Length-Weight Relationship

Revista de Biología Tropical ISSN: 0034-7744 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Brito, Roberto; Gelabert, Rolando; Amador del Ángel, Luís Enrique; Alderete, Ángel; Guevara, Emma Diel variation in the catch of the shrimp Farfantepenaeus duorarum (Decapoda, Penaeidae) and length-weight relationship, in a nursery area of the Terminos Lagoon, Mexico Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 65, núm. 1, 2017, pp. 65-75 Universidad de Costa Rica San Pedro de Montes de Oca, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44950154007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Diel variation in the catch of the shrimp Farfantepenaeus duorarum (Decapoda, Penaeidae) and length-weight relationship, in a nursery area of the Terminos Lagoon, Mexico Roberto Brito, Rolando Gelabert*, Luís Enrique Amador del Ángel, Ángel Alderete & Emma Guevara Centro de Investigación de Ciencias Ambientales, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Autónoma del Carmen. Av. Laguna de Términos s/n, Col. Renovación 2dª Sección C.P. 24155, Ciudad del Carmen, Camp. México; [email protected], [email protected]*, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] * Correspondence Received 02-V-2016. Corrected 06-IX-2016. Accepted 06-X-2016. Abstract: The pink shrimp, Farfantepenaeus duorarum is an important commercial species in the Gulf of Mexico, which supports significant commercial fisheries near Dry Tortugas, in Southern Florida and in Campeche Sound, Southern Gulf of Mexico. -

Shrimps, Lobsters, and Crabs of the Atlantic Coast of the Eastern United States, Maine to Florida

SHRIMPS, LOBSTERS, AND CRABS OF THE ATLANTIC COAST OF THE EASTERN UNITED STATES, MAINE TO FLORIDA AUSTIN B.WILLIAMS SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS Washington, D.C. 1984 © 1984 Smithsonian Institution. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Williams, Austin B. Shrimps, lobsters, and crabs of the Atlantic coast of the Eastern United States, Maine to Florida. Rev. ed. of: Marine decapod crustaceans of the Carolinas. 1965. Bibliography: p. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: SI 18:2:SL8 1. Decapoda (Crustacea)—Atlantic Coast (U.S.) 2. Crustacea—Atlantic Coast (U.S.) I. Title. QL444.M33W54 1984 595.3'840974 83-600095 ISBN 0-87474-960-3 Editor: Donald C. Fisher Contents Introduction 1 History 1 Classification 2 Zoogeographic Considerations 3 Species Accounts 5 Materials Studied 8 Measurements 8 Glossary 8 Systematic and Ecological Discussion 12 Order Decapoda , 12 Key to Suborders, Infraorders, Sections, Superfamilies and Families 13 Suborder Dendrobranchiata 17 Infraorder Penaeidea 17 Superfamily Penaeoidea 17 Family Solenoceridae 17 Genus Mesopenaeiis 18 Solenocera 19 Family Penaeidae 22 Genus Penaeus 22 Metapenaeopsis 36 Parapenaeus 37 Trachypenaeus 38 Xiphopenaeus 41 Family Sicyoniidae 42 Genus Sicyonia 43 Superfamily Sergestoidea 50 Family Sergestidae 50 Genus Acetes 50 Family Luciferidae 52 Genus Lucifer 52 Suborder Pleocyemata 54 Infraorder Stenopodidea 54 Family Stenopodidae 54 Genus Stenopus 54 Infraorder Caridea 57 Superfamily Pasiphaeoidea 57 Family Pasiphaeidae 57 Genus -

Invertebrate ID Guide

11/13/13 1 This book is a compilation of identification resources for invertebrates found in stomach samples. By no means is it a complete list of all possible prey types. It is simply what has been found in past ChesMMAP and NEAMAP diet studies. A copy of this document is stored in both the ChesMMAP and NEAMAP lab network drives in a folder called ID Guides, along with other useful identification keys, articles, documents, and photos. If you want to see a larger version of any of the images in this document you can simply open the file and zoom in on the picture, or you can open the original file for the photo by navigating to the appropriate subfolder within the Fisheries Gut Lab folder. Other useful links for identification: Isopods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-33/htm/doc.html http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-48/htm/doc.html Polychaetes http://web.vims.edu/bio/benthic/polychaete.html http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-34/htm/doc.html Cephalopods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-44/htm/doc.html Amphipods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-67/htm/doc.html Molluscs http://www.oceanica.cofc.edu/shellguide/ http://www.jaxshells.org/slife4.htm Bivalves http://www.jaxshells.org/atlanticb.htm Gastropods http://www.jaxshells.org/atlantic.htm Crustaceans http://www.jaxshells.org/slifex26.htm Echinoderms http://www.jaxshells.org/eich26.htm 2 PROTOZOA (FORAMINIFERA) ................................................................................................................................ 4 PORIFERA (SPONGES) ............................................................................................................................................... 4 CNIDARIA (JELLYFISHES, HYDROIDS, SEA ANEMONES) ............................................................................... 4 CTENOPHORA (COMB JELLIES)............................................................................................................................ -

Farfantepenaeus Duorarum Spatiotemporal Abundance Trends Along an Urban, Subtropical Shoreline Slated for Restoration

RESEARCH ARTICLE Pink shrimp Farfantepenaeus duorarum spatiotemporal abundance trends along an urban, subtropical shoreline slated for restoration 1,2 2 3 2,3 Ian C. ZinkID *, Joan A. Browder , Diego Lirman , Joseph E. Serafy 1 Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Science, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric a1111111111 Science, University of Miami, Miami, FL, United States of America, 2 Protected Resources and Biodiversity Division, Southeast Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and a1111111111 Atmospheric Administration, Miami, FL, United States of America, 3 Marine Biology and Ecology a1111111111 Department, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, Miami, FL, United a1111111111 States of America a1111111111 * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Citation: Zink IC, Browder JA, Lirman D, Serafy JE The Biscayne Bay Coastal Wetlands (BBCW) project of the Comprehensive Everglades (2018) Pink shrimp Farfantepenaeus duorarum Restoration Plan (CERP) aims to reduce point-source freshwater discharges and spread spatiotemporal abundance trends along an urban, freshwater flow along the mainland shoreline of southern Biscayne Bay. These actions will subtropical shoreline slated for restoration. PLoS be taken to approximate conditions in the coastal wetlands and bay that existed prior to con- ONE 13(11): e0198539. https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0198539 struction of canals and water control structures. An increase in pink shrimp (Farfantepe- naeus duorarum) density to � 2 individuals m-2 during the wet season (i.e., August-October) Editor: Suzannah Rutherford, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, UNITED STATES along the mainland shoreline was previously proposed as an indication of BBCW success. This study examined pre-BBCW baseline densities and compared them with the proposed Received: May 18, 2018 target. -

96-113 Relative Virulence of White Spot Syndrome Virus

Annals of Tropical Research 34[1]:96-113(2012) © VSU, Leyte, Philippines Quantification of the Relative Virulence of White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV) in the Penaeid Shrimps Litopenaeus vannamei (Boone, 1931) and Farfantepenaeus duorarum (Burkenroad, 1939) by Quantitative Real Time PCR Rey J. dela Calzada1, Jeffrey M. Lotz2 1 Department of Fisheries, Visayas State University-Tolosa, Tanghas , Tolosa, Leyte 6503 Philippines, 2 Department of Coastal Sciences,The University of Southern Mississippi, Gulf Coast Research Laboratory, PO Box 7000, Ocean Springs, Mississippi 39566-7000, USA ABSTRACT The relative virulence of the China isolate of white spot syndrome virus (WSSV-CN) in the penaeid shrimps Litopenaeus vannamei and Farfantepenaeus duorarum, was assessed by a comparison of 7-d median lethal dose (LD50), survival curve, and mean lethal load after exposure by injection. Shrimps were injected intramuscularly with known WSSV dose. Median lethal dose of L. vannamei was lower than that of F. duorarum. Log LD50 in L.vannamei was 4.20 WSSV genome -1 - copies µg total DNA. Log LD50 in F.duorarum was 5.32 WSSV genome copies µg 1total DNA. Median survival times of L. vannamei and F. duorarum injected with 104 and 105 WSSV genome copies were 54.17 h and 38.91 h, respectively for L. vannamei whereas they were 119.58 h and 82.67 h, respectively for F. duorarum. Mean log of the WSSV lethal load for L. vannamei was 9.34(SE ± 9.09) copies µg-1 of total DNA and for F. duorarum was 11.80 (SE ± 11.55). No significant difference was noted in lethal load for the shrimp species using Student's t-test. -

Observer Training Manual National Marine Fisheries Service Southeast

Characterization of the US Gulf of Mexico and Southeastern Atlantic Otter Trawl and Bottom Reef Fish Fisheries Observer Training Manual National Marine Fisheries Service Southeast Fisheries Science Center Galveston Laboratory September 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS National Overview ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 Project Overview ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 8 Observer Program Guidelines and Safety ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 15 Observer Safety ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 15 Medical Fitness for Sea ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 15 Training ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 15 Before Deployment on Vessel ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 16 Seven Steps to Survival ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 18 Donning an Immersion Suit ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 20 Safety Aboard Vessels ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 22 Safety At‐Sea Transfers ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 23 Off‐Shore Communications ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 24 Advise to Women Going to Sea ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 27 Summary: What You Need to Know About Sea Survival ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 29 Deployment on Vessel -

Web-ICE Aquatic Database Documentation

OP-GED/BPRB/MB/2016-03-001 February 24, 2016 ICE Aquatic Toxicity Database Version 3.3 Documentation Prepared by: Sandy Raimondo, Crystal R. Lilavois, Morgan M. Willming and Mace G. Barron U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory Gulf Ecology Division Gulf Breeze, Fl 32561 1 OP-GED/BPRB/MB/2016-03-001 February 24, 2016 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 3 2 Data Sources ........................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 ECOTOX ............................................................................................................................ 4 2.2 Ambient Water Quality Criteria (AWQC) ......................................................................... 4 2.3 Office of Pesticide Program (OPP) Ecotoxicity Database ................................................. 4 2.4 OPPT Premanufacture Notification (PMN) ...................................................................... 5 2.5 High Production Volume (HPV) ........................................................................................ 5 2.6 Mayer and Ellersieck 1986 ............................................................................................... 5 2.7 ORD .................................................................................................................................. -

Biscayne Bay Commercial Pink Shrimp, Farfantepenaeus Duorarum, Fisheries, 1986–2005

Biscayne Bay Commercial Pink Shrimp, Farfantepenaeus duorarum, Fisheries, 1986–2005 DARLENE R. JOHNSON, JOAN A. BROWDER, PAMELA BROWN-EYO, and MICHAEL B. ROBBLEE Introduction brown shrimp F. aztecus. The average shrimp species caught in Biscayne Bay annual Florida shrimp catch for the (Tabb and Kenny, 1968; Campos and Shrimp are Florida’s most valuable 3 and popular seafood (IFAS1). Three period from 2000 to 2010 was more than Berkeley, 2003; Berkeley et al. ). The 20 million pounds (9,072 kg) and was spotted pink shrimp, F. brasiliensis, commercially important species of 1 penaeid shrimp occur on both Florida worth $40 million at the dock (IFAS ). also occurs in the bay (Criales et al., Total annual landings of pink shrimp on 2000), but it appears inconsequential coasts: white, Litopenaeus setiferus; 4 pink, Farfantepenaeus. duorarum; and the west Florida coast greatly outweigh in trawl catches (Browder et al. ) and those on the east coast; however, Miami- is not reported separately in landings 1 IFAS, University of Florida. Wild vs. farmed Dade County is the only county on the data. Biscayne Bay pink shrimp fisher- shrimp: the choice is yours. Fact sheet. 3 p. east coast having pink shrimp landings ies provide only a small component of Available online at http://collier.ifas.ufl.edu/Sea- Grant/pubs/Shrimp%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf. greater than 10,000 pounds (4,536 kg) Florida’s overall pink shrimp landings (FFWCC2). and ex-vessel value; however, both Here we describe the pink shrimp bait and food shrimp are commercially Darlene R. Johnson is with the University of Miami, Cooperative Institute for Marine and fisheries of Biscayne Bay, Florida, by caught in Biscayne Bay and, together, Atmospheric Studies, Rosenstiel School of means of the landings and effort data ac- represent the bay’s most important Marine and Atmospheric Science, 4600 Ricken- backer Causeway, Miami, Florida 33149. -

Feeding of Farfantepenaeus Paulensis (Pérez-Farfante, 1967) (Crustacea: Penaeidae) Inside and Outside Experimental Pen-Culture in Southern Brazil

Feeding of Farfantepenaeus paulensis (Pérez-Farfante, 1967) (Crustacea: Penaeidae) inside and outside experimental pen-culture in southern Brazil 1,2 1 3 PABLO JORGENSEN , CARLOS E. BEMVENUTI & CLARA M. HEREU 1Laboratório de Ecologia de Invertebrados Bentônicos, Departamento de Oceanografia, Fundação Universidade Federal do Rio Grande (FURG), Av. Itália Km 8, 96201-900 Rio Grande, RS, Brasil; 2Present address: El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Apdo. Postal 424, Chetumal, Quintana Roo 77900. México; 3El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Apdo. Postal 424, Chetumal, Quintana Roo 77900. México. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. We assessed the value of benthic macroinvertebrates to the diet of Farfantepenaeus paulensis juveniles in experimental pen-cages after three independent rearing periods of 20, 40 and 60 days each. For each time period we initially stocked 3 pen-cages with 60 shrimps m-2 supplemented with ration (treatment RS), and 3 pen-cages with 60 shrimps m-2 without ration (WR). The diet of captive shrimps was compared with the diet of free shrimps (C). Shrimps fed preferentially on benthic preys. Captive shrimps extended their activity to daylight hours and consumed a significant amount of vegetation, likely in response to a severe decrease of macroinvertebrate density passed 20 and 40 days. After 60 days, the diet of the few survivors of F. paulensis in pen-cages without ration (WR) approached the diet of shrimps in the natural environment (C). These similarities were explained by the recovery of macroinvertebrates populations to relaxation from high predation pressure during the last 20 days of the experiment in WR pens. -

St. Lucie, Units 1 and 2

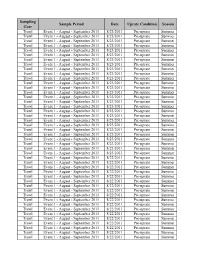

Sampling Sample Period Date Uprate Condition Season Gear Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event -

Sampling and Evaluation of White Spot Syndrome Virus in Commercially Important Atlantic Penaeid Shrimp Stocks

DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Vol. 59: 179–185, 2004 Published June 11 Dis Aquat Org Sampling and evaluation of white spot syndrome virus in commercially important Atlantic penaeid shrimp stocks Robert W. Chapman*, Craig L. Browdy, Suzanne Savin, Sarah Prior, Elizabeth Wenner South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Marine Resources Research Institute, 217 Ft. Johnson Road, Charleston, South Carolina 29412, USA ABSTRACT: In 1997, white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) was discovered in shrimp culture facilities in South Carolina, USA. This disease was known to cause devastating mortalities in cultured popula- tions in Southeast Asia and prompted concern for the health of wild populations in the USA. Our study surveyed wild shrimp populations for the presence of WSSV by utilizing molecular diagnostics and bioassay techniques. A total of 1150 individuals (586 Litopenaeus setiferus, 477 Farfantepenaeus aztecus and 87 F. dourarum) were examined for the presence of WSSV DNA by PCR. A total of 32 individuals tested positive and were used in a bioassay to examine the transmission of disease to healthy individuals of the culture species L. vannamei. DNA sequencing of PCR products from a pos- itive individual confirmed that the positive individuals carried WSSV DNA. Significant mortalities were seen in test shrimp injected with tissue extracts from heavily infected wild shrimp. These data confirm the existence of WSSV in wild shrimp stocks along the Atlantic Coast and that the virus can cause mortalities in cultured stocks. KEY WORDS: Penaeid · Shrimp · White spot virus · Disease · Native species · PCR Resale or republication not permitted without written consent of the publisher INTRODUCTION large part of this decline can be traced to shrimp virus problems. -

Decapoda (Crustacea) of the Gulf of Mexico, with Comments on the Amphionidacea

•59 Decapoda (Crustacea) of the Gulf of Mexico, with Comments on the Amphionidacea Darryl L. Felder, Fernando Álvarez, Joseph W. Goy, and Rafael Lemaitre The decapod crustaceans are primarily marine in terms of abundance and diversity, although they include a variety of well- known freshwater and even some semiterrestrial forms. Some species move between marine and freshwater environments, and large populations thrive in oligohaline estuaries of the Gulf of Mexico (GMx). Yet the group also ranges in abundance onto continental shelves, slopes, and even the deepest basin floors in this and other ocean envi- ronments. Especially diverse are the decapod crustacean assemblages of tropical shallow waters, including those of seagrass beds, shell or rubble substrates, and hard sub- strates such as coral reefs. They may live burrowed within varied substrates, wander over the surfaces, or live in some Decapoda. After Faxon 1895. special association with diverse bottom features and host biota. Yet others specialize in exploiting the water column ment in the closely related order Euphausiacea, treated in a itself. Commonly known as the shrimps, hermit crabs, separate chapter of this volume, in which the overall body mole crabs, porcelain crabs, squat lobsters, mud shrimps, plan is otherwise also very shrimplike and all 8 pairs of lobsters, crayfish, and true crabs, this group encompasses thoracic legs are pretty much alike in general shape. It also a number of familiar large or commercially important differs from a peculiar arrangement in the monospecific species, though these are markedly outnumbered by small order Amphionidacea, in which an expanded, semimem- cryptic forms. branous carapace extends to totally enclose the compara- The name “deca- poda” (= 10 legs) originates from the tively small thoracic legs, but one of several features sepa- usually conspicuously differentiated posteriormost 5 pairs rating this group from decapods (Williamson 1973).