Plant Life of Western Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplementary Materialsupplementary Material

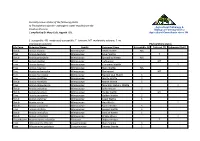

10.1071/BT13149_AC © CSIRO 2013 Australian Journal of Botany 2013, 61(6), 436–445 SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Comparative dating of Acacia: combining fossils and multiple phylogenies to infer ages of clades with poor fossil records Joseph T. MillerA,E, Daniel J. MurphyB, Simon Y. W. HoC, David J. CantrillB and David SeiglerD ACentre for Australian National Biodiversity Research, CSIRO Plant Industry, GPO Box 1600 Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. BRoyal Botanic Gardens Melbourne, Birdwood Avenue, South Yarra, Vic. 3141, Australia. CSchool of Biological Sciences, Edgeworth David Building, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. DDepartment of Plant Biology, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801, USA. ECorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Table S1 Materials used in the study Taxon Dataset Genbank Acacia abbreviata Maslin 2 3 JF420287 JF420065 JF420395 KC421289 KC796176 JF420499 Acacia adoxa Pedley 2 3 JF420044 AF523076 AF195716 AF195684; AF195703 Acacia ampliceps Maslin 1 KC421930 EU439994 EU811845 Acacia anceps DC. 2 3 JF420244 JF420350 JF419919 JF420130 JF420456 Acacia aneura F.Muell. ex Benth 2 3 JF420259 JF420036 JF420366 JF419935 JF420146 KF048140 Acacia aneura F.Muell. ex Benth. 1 2 3 JF420293 JF420402 KC421323 JQ248740 JF420505 Acacia baeuerlenii Maiden & R.T.Baker 2 3 JF420229 JQ248866 JF420336 JF419909 JF420115 JF420448 Acacia beckleri Tindale 2 3 JF420260 JF420037 JF420367 JF419936 JF420147 JF420473 Acacia cochlearis (Labill.) H.L.Wendl. 2 3 KC283897 KC200719 JQ943314 AF523156 KC284140 KC957934 Acacia cognata Domin 2 3 JF420246 JF420022 JF420352 JF419921 JF420132 JF420458 Acacia cultriformis A.Cunn. ex G.Don 2 3 JF420278 JF420056 JF420387 KC421263 KC796172 JF420494 Acacia cupularis Domin 2 3 JF420247 JF420023 JF420353 JF419922 JF420133 JF420459 Acacia dealbata Link 2 3 JF420269 JF420378 KC421251 KC955787 JF420485 Acacia dealbata Link 2 3 KC283375 KC200761 JQ942686 KC421315 KC284195 Acacia deanei (R.T.Baker) M.B.Welch, Coombs 2 3 JF420294 JF420403 KC421329 KC955795 & McGlynn JF420506 Acacia dempsteri F.Muell. -

Acacia Cochlearis RIGID WATTLE (Labill.) H.L.Wendl

Plants of the West Coast family: fabaCeae Acacia cochlearis RIGID WATTLE (Labill.) H.L.Wendl Flowering period: July–October. Description: Bushy, erect to sprawling shrub, 0.5–3 m high and found as solitary plants or in thickets. Leaves to 45 mm long with a sharp point, rigid, with prominent parallel veins. Flower heads globular with up to three produced in each leaf axil. The green-brown pod is flat, to 50 mm long, and produces 10–15 black and usually highly viable seeds. Pollination: Open pollinated by a wide variety of non-specific insects. Sets a moderate amount of seed in good seasons. Distribution: From Lancelin to Israelite Bay where the species grows as solitary plants or in thickets in coastal to near-coastal habitats. Along the coast the species favours stable secondary dunes. Often an indicator of good quality dunes as the species is vulnerable to disturbance. Propagation: Grow from seed collected in December when pods mature. Seed should be hot water treated or lightly abraded with fine sandpaper. Sow in a free-draining soil mix and keep moist. Seedling growth may benefit from incorporation of a little soil taken from the weed- and disease-free soil surface around a parent plant to ensure transfer of the Rhizobium bacteria that are important in nitrogen nutrition of the plant. R. Barrett Habit Uses in restoration: A useful species that reliably establishes in stabilised soil. Must be protected from direct exposure to high winds and is best incorporated into mixed plantings with other shrubs including Acacia rostellifera and Scaevola crassifolia. -

PUBLISHER S Candolle Herbarium

Guide ERBARIUM H Candolle Herbarium Pamela Burns-Balogh ANDOLLE C Jardin Botanique, Geneva AIDC PUBLISHERP U R L 1 5H E R S S BRILLB RI LL Candolle Herbarium Jardin Botanique, Geneva Pamela Burns-Balogh Guide to the microform collection IDC number 800/2 M IDC1993 Compiler's Note The microfiche address, e.g. 120/13, refers to the fiche number and secondly to the individual photograph on each fiche arranged from left to right and from the top to the bottom row. Pamela Burns-Balogh Publisher's Note The microfiche publication of the Candolle Herbarium serves a dual purpose: the unique original plants are preserved for the future, and copies can be made available easily and cheaply for distribution to scholars and scientific institutes all over the world. The complete collection is available on 2842 microfiche (positive silver halide). The order number is 800/2. For prices of the complete collection or individual parts, please write to IDC Microform Publishers, P.O. Box 11205, 2301 EE Leiden, The Netherlands. THE DECANDOLLEPRODROMI HERBARIUM ALPHABETICAL INDEX Taxon Fiche Taxon Fiche Number Number -A- Acacia floribunda 421/2-3 Acacia glauca 424/14-15 Abatia sp. 213/18 Acacia guadalupensis 423/23 Abelia triflora 679/4 Acacia guianensis 422/5 Ablania guianensis 218/5 Acacia guilandinae 424/4 Abronia arenaria 2215/6-7 Acacia gummifera 421/15 Abroniamellifera 2215/5 Acacia haematomma 421/23 Abronia umbellata 221.5/3-4 Acacia haematoxylon 423/11 Abrotanella emarginata 1035/2 Acaciahastulata 418/5 Abrus precatorius 403/14 Acacia hebeclada 423/2-3 Acacia abietina 420/16 Acacia heterophylla 419/17-19 Acacia acanthocarpa 423/16-17 Acaciahispidissima 421/22 Acacia alata 418/3 Acacia hispidula 419/2 Acacia albida 422/17 Acacia horrida 422/18-20 Acacia amara 425/11 Acacia in....? 423/24 Acacia amoena 419/20 Acacia intertexta 421/9 Acacia anceps 419/5 Acacia julibross. -

Jervis Bay Territory Page 1 of 50 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region (Blank), Jervis Bay Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Inventory of Taxa for the Fitzgerald River National Park

Flora Survey of the Coastal Catchments and Ranges of the Fitzgerald River National Park 2013 Damien Rathbone Department of Environment and Conservation, South Coast Region, 120 Albany Hwy, Albany, 6330. USE OF THIS REPORT Information used in this report may be copied or reproduced for study, research or educational purposed, subject to inclusion of acknowledgement of the source. DISCLAIMER The author has made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information used. However, the author and participating bodies take no responsibiliy for how this informrion is used subsequently by other and accepts no liability for a third parties use or reliance upon this report. CITATION Rathbone, DA. (2013) Flora Survey of the Coastal Catchments and Ranges of the Fitzgerald River National Park. Unpublished report. Department of Environment and Conservation, Western Australia. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank many people that provided valable assistance and input into the project. Sarah Barrett, Anita Barnett, Karen Rusten, Deon Utber, Sarah Comer, Charlotte Mueller, Jason Peters, Roger Cunningham, Chris Rathbone, Carol Ebbett and Janet Newell provided assisstance with fieldwork. Carol Wilkins, Rachel Meissner, Juliet Wege, Barbara Rye, Mike Hislop, Cate Tauss, Rob Davis, Greg Keighery, Nathan McQuoid and Marco Rossetto assissted with plant identification. Coralie Hortin, Karin Baker and many other members of the Albany Wildflower society helped with vouchering of plant specimens. 2 Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. -

South West Region

Regional Services Division – South West Region South West Region ‐ Parks & Wildlife and FPC Disturbance Operations Flora and Vegetation Survey Assessment Form 1. Proposed Operations: (to be completed by proponent) NBX0217 Summary of Proposed Operation: Road Construction and Timber Harvesting New road construction – 3.75km Existing road upgrade – 14.9km New gravel pit construction – 2ha (exploration area) Contact Person and Contact Details: Adam Powell [email protected] 0427 191 332 Area of impact; District/Region, State Forest Block, Coupe/Compartment (shapefile to be provided): Blackwood District South West Region Barrabup 0317 Period of proposed disturbance: November 2016 to December 2017 1 2.Desktop Assessment: (to be completed by the Region) ‐ Check Forest Ecosystem reservation. Forest Ecosystems proposed for impact: Jarrah Forest‐Blackwood Plateau, Shrub, herb and sedgelands, Darling Scarp Y Are activities in a Forest Ecosystem that triggers informal reservation under the FMP? The Darling Scarp Forest Ecosystem is a Poorly Reserved Forest Ecosystem and needs to be protected as an Informal Reserve under the Forest Management Plan (Appendix 11) ‐ Check Vegetation Complexes, extents remaining uncleared and in reservation (DEC 2007/EPA 2006). Vegetation Complex Pre‐European extent (%) Pre‐European extent (Ha) Extent in formal/informal reservation (%) Bidella (BD) 94% 44,898 47% Darling Scarp (DS) Figures not available Corresponds to Darling Scarp Forest Ecosystem extent Gale (GA) 80% 899 17% Jalbarragup (JL) 91% 14,786 32% Kingia (KI) 96% 97,735 34% Telerah (TL) 92% 25,548 33% Wishart (WS2) 84% 2,796 35% Y Do any complexes trigger informal reservation under the FMP? Darling Scarp complex as discussed above Y Are any complexes significant as per EPA regionally significant vegetation? Gale (GA) complex is cleared below the recommended retention of 1,500ha (Molloy et.al 2007) ‐ Check Threatened flora and TEC/PEC databases over an appropriate radius of the disturbance boundary. -

Vertebrate Fauna in the Southern Forests of Western Australia

tssN 0085-8129 ODC151:146 VertebrateFauna in The SouthernForests of WesternAustralia A Survey P. CHRISTENSEN,A. ANNELS, G. LIDDELOW AND P. SKINNER FORESTS DEPARTMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA BULLETIN94, 1985 T:- VertebrateFauna in The SouthernForests of WesternAustralia A Survey By P. CHRISTENSEN, A. ANNELS, G. LIDDELOW AND P. SKINNER Edited by Liana ChristensenM.A. (w.A.I.T.) Preparedfor Publicationby Andrew C.A. Cribb B.A. (U.W.A.) P.J. McNamara Acting Conservator of Forcsts 1985 I I r FRONT COVER The Bush R.at (Rattus fuscipes): the most abundantof the native mammals recordedby the surueyteams in WesternAustralia's southernforests. Coverphotograph: B. A. & A. C. WELLS Printed in WesternAustralia Publishedby the ForestsDepartmeDt of WesternAustralia Editor MarianneR.L. Lewis AssistantEditor Andrew C.A. Cribb DesignTrish Ryder CPl9425/7/85- Bf Atthority WILLIAM BENBOW,Aciing Cov€mmenaPrinter, Wesrern Ausrralia + Contents Page SUMMARY SECTION I-INTRODUCTION HistoricalBackground. Recent Perspectives SECTION II-DESCRIPTION OF SURVEY AREA Boundariesand PhysicalFeatures 3 Geology 3 Soils 3 Climate 6 Vegetation 6 VegetationTypes. 8 SECTION III-SURVEY METHODS 13 SECTION IV-SURVEY RESULTSAND LIST OF SPECIES. l6 (A) MAMMALS Discussionof Findings. l6 List of Species (i) IndigenousSpecies .17 (ii) IntroducedSpecies .30 (B) BIRDS Discussionof Findings List of Species .34 (C) REPTILES Discussionof Findings. List of Species. .49 (D) AMPHIBIANS Discussionof Findings. 55 List of Species. 55 (E) FRESHWATER FISH Discussionof Findings. .59 List of Species (i) IndigenousSpecies 59 (ii) IntroducedSpecies 6l SECTION V-GENERALDISCUSSION 63 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 68 REFERENCES 69 APPENDICES I-Results from Fauna Surveys 1912-t982 72 II-Results from Other ResearchStudies '74 Within The SurveyArea 1970-1982. -

Grevillea Study Group

AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS SOCIETY (AUSTRALIA) INC GREVILLEA STUDY GROUP NEWSLETTER NO. 109 – FEBRUARY 2018 GSG NSW Programme 2018 02 | EDITORIAL Leader: Peter Olde, p 0432 110 463 | e [email protected] For details about the NSW chapter please contact Peter, contact via email is preferred. GSG Vic Programme 2018 03 | TAXONOMY Leader: Neil Marriott, 693 Panrock Reservoir Rd, Stawell, Vic. 3380 SOME NOTES ON HOLLY GREVILLEA DNA RESEARCH p 03 5356 2404 or 0458 177 989 | e [email protected] Contact Neil for queries about program for the year. Any members who would PHYLOGENY OF THE HOLLY GREVILLEAS (PROTEACEAE) like to visit the official collection, obtain cutting material or seed, assist in its BASED ON NUCLEAR RIBOSOMAL maintenance, and stay in our cottage for a few days are invited to contact Neil. AND CHLOROPLAST DNA Living Collection Working Bee Labour Day 10-12 March A number of members have offered to come up and help with the ongoing maintenanceof the living collection. Our garden is also open as part of the FJC Rogers Goodeniaceae Seminar in October this year, so there is a lot of tidying up and preparation needed. We think the best time for helpers to come up would be the Labour Day long weekend on 10th-12th March. We 06 | IN THE WILD have lots of beds here, so please register now and book a bed. Otherwise there is lots of space for caravans or tents: [email protected]. We will have a great weekend, with lots of A NEW POPULATION OF GREVILLEA socializing, and working together on the living collection. -

Phytophthora Resistance and Susceptibility Stock List

Currently known status of the following plants to Phytophthora species - pathogenic water moulds from the Agricultural Pathology & Kingdom Protista. Biological Farming Service C ompiled by Dr Mary Cole, Agpath P/L. Agricultural Consultants since 1980 S=susceptible; MS=moderately susceptible; T= tolerant; MT=moderately tolerant; ?=no information available. Phytophthora status Life Form Botanical Name Family Common Name Susceptible (S) Tolerant (T) Unknown (UnK) Shrub Acacia brownii Mimosaceae Heath Wattle MS Tree Acacia dealbata Mimosaceae Silver Wattle T Shrub Acacia genistifolia Mimosaceae Spreading Wattle MS Tree Acacia implexa Mimosaceae Lightwood MT Tree Acacia leprosa Mimosaceae Cinnamon Wattle ? Tree Acacia mearnsii Mimosaceae Black Wattle MS Tree Acacia melanoxylon Mimosaceae Blackwood MT Tree Acacia mucronata Mimosaceae Narrow Leaf Wattle S Tree Acacia myrtifolia Mimosaceae Myrtle Wattle S Shrub Acacia myrtifolia Mimosaceae Myrtle Wattle S Tree Acacia obliquinervia Mimosaceae Mountain Hickory Wattle ? Shrub Acacia oxycedrus Mimosaceae Spike Wattle S Shrub Acacia paradoxa Mimosaceae Hedge Wattle MT Tree Acacia pycnantha Mimosaceae Golden Wattle S Shrub Acacia sophorae Mimosaceae Coast Wattle S Shrub Acacia stricta Mimosaceae Hop Wattle ? Shrubs Acacia suaveolens Mimosaceae Sweet Wattle S Tree Acacia ulicifolia Mimosaceae Juniper Wattle S Shrub Acacia verniciflua Mimosaceae Varnish wattle S Shrub Acacia verticillata Mimosaceae Prickly Moses ? Groundcover Acaena novae-zelandiae Rosaceae Bidgee-Widgee T Tree Allocasuarina littoralis Casuarinaceae Black Sheoke S Tree Allocasuarina paludosa Casuarinaceae Swamp Sheoke S Tree Allocasuarina verticillata Casuarinaceae Drooping Sheoak S Sedge Amperea xipchoclada Euphorbaceae Broom Spurge S Grass Amphibromus neesii Poaceae Swamp Wallaby Grass ? Shrub Aotus ericoides Papillionaceae Common Aotus S Groundcover Apium prostratum Apiaceae Sea Celery MS Herb Arthropodium milleflorum Asparagaceae Pale Vanilla Lily S? Herb Arthropodium strictum Asparagaceae Chocolate Lily S? Shrub Atriplex paludosa ssp. -

Post-Fire Recovery of Woody Plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion

Post-fire recovery of woody plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion Peter J. ClarkeA, Kirsten J. E. Knox, Monica L. Campbell and Lachlan M. Copeland Botany, School of Environmental and Rural Sciences, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, AUSTRALIA. ACorresponding author; email: [email protected] Abstract: The resprouting response of plant species to fire is a key life history trait that has profound effects on post-fire population dynamics and community composition. This study documents the post-fire response (resprouting and maturation times) of woody species in six contrasting formations in the New England Tableland Bioregion of eastern Australia. Rainforest had the highest proportion of resprouting woody taxa and rocky outcrops had the lowest. Surprisingly, no significant difference in the median maturation length was found among habitats, but the communities varied in the range of maturation times. Within these communities, seedlings of species killed by fire, mature faster than seedlings of species that resprout. The slowest maturing species were those that have canopy held seed banks and were killed by fire, and these were used as indicator species to examine fire immaturity risk. Finally, we examine whether current fire management immaturity thresholds appear to be appropriate for these communities and find they need to be amended. Cunninghamia (2009) 11(2): 221–239 Introduction Maturation times of new recruits for those plants killed by fire is also a critical biological variable in the context of fire Fire is a pervasive ecological factor that influences the regimes because this time sets the lower limit for fire intervals evolution, distribution and abundance of woody plants that can cause local population decline or extirpation (Keith (Whelan 1995; Bond & van Wilgen 1996; Bradstock et al. -

Appendix 3 Vertebrate Fauna Assessment

A VERTEBRATE FAUNA ASSESSMENT OF THE CLOVERDALE MINERAL SANDS SURVEY AREA Prepared for Iluka Resources Ltd By Ninox Wildlife Consulting February 2006 i Executive Summary The Cloverdale Mineral Sands Project Area is situated approximately 8 km south of Capel, Western Australia. For this fauna assessment, a wider area was surveyed in order to encompass all of the fauna habitats that could be impacted directly or indirectly by the Project. The area assessed for fauna has been called the Survey Area throughout this report. Much of the Survey Area is located on private property on the Southern Swan Coastal Plain (SSCP), although there is a small area of Vacant Crown Land on the Ludlow River. Much of the area is cleared for agriculture with vegetated road reserves, isolated trees in paddocks and small areas of remnant vegetation, some of which has been fenced from stock grazing. A field assessment of the Project Area and surrounds (Survey Area) was carried out over two days in March 2005 by GHD with additional field work conducted by Ninox Wildlife Consulting in mid October 2005. This assessment incorporated a detailed literature review which included a search of State and Commonwealth vertebrate fauna databases, a review of published literature on the vertebrate fauna of the general area and a review of unpublished records from the general area held by Ninox Wildlife Consulting. A total of 46 species of bird has been recorded within the Survey Area. The results of the literature review showed that a further 78 species could be expected to occur as resident, nomadic, migratory or occasional visitors to the general area. -

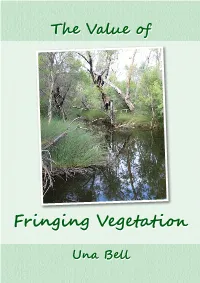

The Value of Fringing Vegetation (Watercourse)

TheThe ValueValue ofof FringingFringing VegetationVegetation UnaUna BellBell Dedicated to the memory of Dr Luke J. Pen An Inspiration to Us All Acknowledgements This booklet is the result of a request from the Jane Brook Catchment Group for a booklet that focuses on the local native plants along creeks in Perth Hills. Thank you to the Jane Brook Catchment Group, Shire of Kalamunda, Environmental Advisory Committee of the Shire of Mundaring, Eastern Metropolitan Regional Council, Eastern Hills Catchment Management Program and Mundaring Community Bank Branch, Bendigo Bank who have all provided funding for this project. Without their support this project would not have come to fruition. Over the course of working on this booklet many people have helped in various ways. I particularly wish to thank past and present Catchment Officers and staff from the Shire of Kalamunda, the Shire of Mundaring and the EMRC, especially Shenaye Hummerston, Kylie del Fante, Renee d’Herville, Craig Wansbrough, Toni Burbidge and Ryan Hepworth, as well as Graham Zemunik, and members of the Jane Brook Catchment Group. I also wish to thank the WA Herbarium staff, especially Louise Biggs, Mike Hislop, Karina Knight and Christine Hollister. Booklet design - Rita Riedel, Shire of Kalamunda About the Author Una Bell has a BA (Social Science) (Hons.) and a Graduate Diploma in Landcare. She is a Research Associate at the WA Herbarium with an interest in native grasses, Community Chairperson of the Eastern Hills Catchment Management Program, a member of the Jane Brook Catchment Group, and has been a bush care volunteer for over 20 years. Other publications include Common Native Grasses of South-West WA.