Activating KIR2DS4 Is Expressed by Uterine NK Cells and Contributes to Successful Pregnancy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

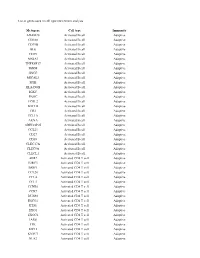

List of Genes Used in Cell Type Enrichment Analysis

List of genes used in cell type enrichment analysis Metagene Cell type Immunity ADAM28 Activated B cell Adaptive CD180 Activated B cell Adaptive CD79B Activated B cell Adaptive BLK Activated B cell Adaptive CD19 Activated B cell Adaptive MS4A1 Activated B cell Adaptive TNFRSF17 Activated B cell Adaptive IGHM Activated B cell Adaptive GNG7 Activated B cell Adaptive MICAL3 Activated B cell Adaptive SPIB Activated B cell Adaptive HLA-DOB Activated B cell Adaptive IGKC Activated B cell Adaptive PNOC Activated B cell Adaptive FCRL2 Activated B cell Adaptive BACH2 Activated B cell Adaptive CR2 Activated B cell Adaptive TCL1A Activated B cell Adaptive AKNA Activated B cell Adaptive ARHGAP25 Activated B cell Adaptive CCL21 Activated B cell Adaptive CD27 Activated B cell Adaptive CD38 Activated B cell Adaptive CLEC17A Activated B cell Adaptive CLEC9A Activated B cell Adaptive CLECL1 Activated B cell Adaptive AIM2 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive BIRC3 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive BRIP1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCL20 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCL4 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCL5 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCNB1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCR7 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive DUSP2 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive ESCO2 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive ETS1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive EXO1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive EXOC6 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive IARS Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive ITK Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive KIF11 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive KNTC1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive NUF2 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive PRC1 Activated -

Propranolol-Mediated Attenuation of MMP-9 Excretion in Infants with Hemangiomas

Supplementary Online Content Thaivalappil S, Bauman N, Saieg A, Movius E, Brown KJ, Preciado D. Propranolol-mediated attenuation of MMP-9 excretion in infants with hemangiomas. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4773 eTable. List of All of the Proteins Identified by Proteomics This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/01/2021 eTable. List of All of the Proteins Identified by Proteomics Protein Name Prop 12 mo/4 Pred 12 mo/4 Δ Prop to Pred mo mo Myeloperoxidase OS=Homo sapiens GN=MPO 26.00 143.00 ‐117.00 Lactotransferrin OS=Homo sapiens GN=LTF 114.00 205.50 ‐91.50 Matrix metalloproteinase‐9 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MMP9 5.00 36.00 ‐31.00 Neutrophil elastase OS=Homo sapiens GN=ELANE 24.00 48.00 ‐24.00 Bleomycin hydrolase OS=Homo sapiens GN=BLMH 3.00 25.00 ‐22.00 CAP7_HUMAN Azurocidin OS=Homo sapiens GN=AZU1 PE=1 SV=3 4.00 26.00 ‐22.00 S10A8_HUMAN Protein S100‐A8 OS=Homo sapiens GN=S100A8 PE=1 14.67 30.50 ‐15.83 SV=1 IL1F9_HUMAN Interleukin‐1 family member 9 OS=Homo sapiens 1.00 15.00 ‐14.00 GN=IL1F9 PE=1 SV=1 MUC5B_HUMAN Mucin‐5B OS=Homo sapiens GN=MUC5B PE=1 SV=3 2.00 14.00 ‐12.00 MUC4_HUMAN Mucin‐4 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MUC4 PE=1 SV=3 1.00 12.00 ‐11.00 HRG_HUMAN Histidine‐rich glycoprotein OS=Homo sapiens GN=HRG 1.00 12.00 ‐11.00 PE=1 SV=1 TKT_HUMAN Transketolase OS=Homo sapiens GN=TKT PE=1 SV=3 17.00 28.00 ‐11.00 CATG_HUMAN Cathepsin G OS=Homo -

Pan-KIR2DL NK-Receptor Antibodies and Their Use in Diagnostik and Therapy

(19) TZZ _ T (11) EP 2 287 195 A2 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 23.02.2011 Bulletin 2011/08 C07K 16/28 (2006.01) G01N 33/52 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 10178924.6 (22) Date of filing: 01.07.2005 (84) Designated Contracting States: • Romagne, François AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR 13600 La Ciotat (FR) HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC NL PL PT RO SE SI • Wagtmann, Peter, Andreas, Nicolai, Reumert SK TR 2960 Rungsted Kyst (DK) • Svendsen, Ivan (30) Priority: 06.01.2005 DK 200500025 2765 Smorum (DK) 01.07.2004 PCT/DK2004/000470 • Zahn, Stefan 01.07.2004 PCT/IB2004/002464 2750 Ballerup (DK) • Svensson, Anders (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in 21746 Malmö (DK) accordance with Art. 76 EPC: • Thorolfsson, Matthias 05758642.2 / 1 791 868 2920 Charlottenlund (DK) • Berg Padkaer, Soren (71) Applicants: 3500 Vaerlose (DK) • Novo Nordisk A/S • Kjaergaard, Kristian 2880 Bagsvaerd (DK) 2750 Ballerup (DK) • Innate Pharma • Spee, Pieter 13009 Marseille (FR) 3450 Allerod (DK) • Universita di Genova • Wilken, Michael 16132 Genova (IT) 3390 Hundested (DK) (72) Inventors: (74) Representative: Gallois, Valérie et al • Moretta, Alessandro Cabinet BECKER & ASSOCIES 16133 Genova (IT) 25, rue Louis Le Grand • Della Chiesa, Mariella 75002 Paris (FR) 16132 Genova (IT) • Andre, Pascale Remarks: 13006 Marseille (FR) This application was filed on 23-09-2010 as a • Gauthier, Laurent divisional application to the application mentioned 13008 Marseille (FR) under INID code 62. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Borne, Richard (2019) Natural Killer (NK) Cell Receptor Expression in Cattle: Development of a Pipeline for Accurate Quantification of RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) Data

Borne, Richard (2019) Natural Killer (NK) cell receptor expression in cattle: development of a pipeline for accurate quantification of RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) data. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/71955/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Natural Killer (NK) cell receptor expression in cattle: development of a pipeline for accurate quantification of RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) data Richard Borne BSc. (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD College of Medical, Veterinary & Life Sciences University of Glasgow September 2018 2 Abstract Cattle have undergone significant gene expansion within two of the major NK receptor encoding complexes, the leukocyte receptor complex (LRC) and natural killer complex (NKC). This expansion has resulted in a number of highly similar genes densely packed within each complex. The genes can be highly polymorphic and encode for fundamentally important receptors for controlling the functional response of NK cells. Understanding the nature of transcription of the LRC and NKC genes is required to confirm existing gene models, predicted functional status and also their distribution in cell and tissue types. -

Gene List HTG Edgeseq Immuno-Oncology Assay

Gene List HTG EdgeSeq Immuno-Oncology Assay Adhesion ADGRE5 CLEC4A CLEC7A IBSP ICAM4 ITGA5 ITGB1 L1CAM MBL2 SELE ALCAM CLEC4C DST ICAM1 ITGA1 ITGA6 ITGB2 LGALS1 MUC1 SVIL CDH1 CLEC5A EPCAM ICAM2 ITGA2 ITGAL ITGB3 LGALS3 NCAM1 THBS1 CDH5 CLEC6A FN1 ICAM3 ITGA4 ITGAM ITGB4 LGALS9 PVR THY1 Apoptosis APAF1 BCL2 BID CARD11 CASP10 CASP8 FADD NOD1 SSX1 TP53 TRAF3 BCL10 BCL2L1 BIRC5 CASP1 CASP3 DDX58 NLRP3 NOD2 TIMP1 TRAF2 TRAF6 B-Cell Function BLNK BTLA CD22 CD79A FAS FCER2 IKBKG PAX5 SLAMF1 SLAMF7 SPN BTK CD19 CD24 EBF4 FASLG IKBKB MS4A1 RAG1 SLAMF6 SPI1 Cell Cycle ABL1 ATF1 ATM BATF CCND1 CDK1 CDKN1B NCL RELA SSX1 TBX21 TP53 ABL2 ATF2 AXL BAX CCND3 CDKN1A EGR1 REL RELB TBK1 TIMP1 TTK Cell Signaling ADORA2A DUSP4 HES1 IGF2R LYN MAPK1 MUC1 NOTCH1 RIPK2 SMAD3 STAT5B AKT3 DUSP6 HES5 IKZF1 MAF MAPK11 MYC PIK3CD RNF4 SOCS1 STAT6 BCL6 ELK1 HEY1 IKZF2 MAP2K1 MAPK14 NFATC1 PIK3CG RORC SOCS3 SYK CEBPB EP300 HEY2 IKZF3 MAP2K2 MAPK3 NFATC3 POU2F2 RUNX1 SPINK5 TAL1 CIITA ETS1 HEYL JAK1 MAP2K4 MAPK8 NFATC4 PRKCD RUNX3 STAT1 TCF7 CREB1 FLT3 HMGB1 JAK2 MAP2K7 MAPKAPK2 NFKB1 PRKCE S100B STAT2 TYK2 CREB5 FOS HRAS JAK3 MAP3K1 MEF2C NFKB2 PTEN SEMA4D STAT3 CREBBP GATA3 IGF1R KIT MAP3K5 MTDH NFKBIA PYCARD SMAD2 STAT4 Chemokine CCL1 CCL16 CCL20 CCL25 CCL4 CCR2 CCR7 CX3CL1 CXCL12 CXCL3 CXCR1 CXCR6 CCL11 CCL17 CCL21 CCL26 CCL5 CCR3 CCR9 CX3CR1 CXCL13 CXCL5 CXCR2 MST1R CCL13 CCL18 CCL22 CCL27 CCL7 CCR4 CCRL2 CXCL1 CXCL14 CXCL6 CXCR3 PPBP CCL14 CCL19 CCL23 CCL28 CCL8 CCR5 CKLF CXCL10 CXCL16 CXCL8 CXCR4 XCL2 CCL15 CCL2 CCL24 CCL3 CCR1 CCR6 CMKLR1 CXCL11 CXCL2 CXCL9 CXCR5 -

Type of the Paper (Article

Supplementary figures and tables E g r 1 F g f2 F g f7 1 0 * 5 1 0 * * e e e * g g g * n n n * a a a 8 4 * 8 h h h * c c c d d d * l l l o o o * f f f * n n n o o o 6 3 6 i i i s s s s s s e e e r r r p p p x x x e e e 4 2 4 e e e n n n e e e g g g e e e v v v i i i t t t 2 1 2 a a a l l l e e e R R R 0 0 0 c o n tro l u n in fla m e d in fla m e d c o n tro l u n in fla m e d in fla m e d c o n tro l u n in fla m e d in fla m e d J a k 2 N o tc h 2 H if1 * 3 4 6 * * * e e e g g g n n n a a * * a * h h * h c c c 3 * d d * d l l l * o o o f f 2 f 4 n n n o o o i i i s s s s s s e e e r r 2 r p p p x x x e e e e e e n n n e e 1 e 2 g g g e e 1 e v v v i i i t t t a a a l l l e e e R R R 0 0 0 c o n tro l u n in fla m e d in fla m e d c o n tro l u n in fla m e d in fla m e d c o n tro l u n in fla m e d in fla m e d Z e b 2 C d h 1 S n a i1 * * 7 1 .5 4 * * e e e g g g 6 n n n * a a a * h h h c c c 3 * d d d l l l 5 o o o f f f 1 .0 * n n n * o o o i i i 4 * s s s s s s e e e r r r 2 p p p x x x 3 e e e e e e n n n e e e 0 .5 g g g 2 e e e 1 v v v i i i t t t a a a * l l l e e e 1 * R R R 0 0 .0 0 c o n tro l u n in fla m e d in fla m e d c o n tro l u n in fla m e d in fla m e d c o n tro l u n in fla m e d in fla m e d M m p 9 L o x V im 2 0 0 2 0 8 * * * e e e * g g g 1 5 0 * n n n * a a a * h h h * c c c 1 5 * 6 d d d l l l 1 0 0 o o o f f f n n n o o o i i i 5 0 s s s s s s * e e e r r r 1 0 4 3 0 p p p * x x x e e e * e e e n n n e e e 2 0 g g g e e e 5 2 v v v i i i t t t a a a l l l 1 0 e e e R R R 0 0 0 c o n tro l u n in fla m e d in fla m e d c o n tro l u n in fla m e d in fla m e d c o n tro l u n in fla m e d in fla m e d Supplementary Figure 1. -

Systems Analysis of Protective Immune Responses to RTS,S Malaria Vaccination in Humans

Systems analysis of protective immune responses to RTS,S malaria vaccination in humans Dmitri Kazmina,1, Helder I. Nakayab,1, Eva K. Leec, Matthew J. Johnsond, Robbert van der Moste, Robert A. van den Bergf, W. Ripley Ballouf, Erik Jongerte, Ulrike Wille-Reeceg, Christian Ockenhouseg, Alan Aderemh, Daniel E. Zakh, Jerald Sadoffi, Jenny Hendriksi, Jens Wrammerta, Rafi Ahmeda,2, and Bali Pulendrana,j,2 aEmory Vaccine Center, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30329; bSchool of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Sao Paulo, São Paulo 05508, Brazil; cSchool of Industrial and Systems Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA 30332; dCenter for Genome Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55108; eGSK Vaccines, Rixensart 1330, Belgium; fGSK Vaccines, Rockville, MD 20850; gProgram for Appropriate Technology in Health-Malaria Vaccine Initiative, Washington, DC 20001; hCenter for Infectious Disease Research, Seattle, WA 98109; iCrucell, Leiden 2333, The Netherlands; and jDepartment of Pathology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322 Contributed by Rafi Ahmed, January 4, 2017 (sent for review December 19, 2016; reviewed by Elias Haddad and Robert Seder) RTS,S is an advanced malaria vaccine candidate and confers trials conducted in malaria endemic areas in Africa proved the significant protection against Plasmodium falciparum infection in vaccine to be partially protective in adults (9), children (10, 11), humans. Little is known about the molecular mechanisms driving and infants (12, 13). These results were further confirmed in a vaccine immunity. Here, we applied a systems biology approach phase III trial in sub-Saharan Africa (14–17) in which 55.8% to study immune responses in subjects receiving three consecutive efficacy against clinical malaria was observed over the first 12 mo immunizations with RTS,S (RRR), or in those receiving two immuni- of follow-up in children of 5–17 mo (14). -

Natural Killer Cell Lymphoma Shares Strikingly Similar Molecular Features

Leukemia (2011) 25, 348–358 & 2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0887-6924/11 www.nature.com/leu ORIGINAL ARTICLE Natural killer cell lymphoma shares strikingly similar molecular features with a group of non-hepatosplenic cd T-cell lymphoma and is highly sensitive to a novel aurora kinase A inhibitor in vitro J Iqbal1, DD Weisenburger1, A Chowdhury2, MY Tsai2, G Srivastava3, TC Greiner1, C Kucuk1, K Deffenbacher1, J Vose4, L Smith5, WY Au3, S Nakamura6, M Seto6, J Delabie7, F Berger8, F Loong3, Y-H Ko9, I Sng10, X Liu11, TP Loughran11, J Armitage4 and WC Chan1, for the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project 1Department of Pathology and Microbiology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA; 2Eppley Institute for Research in Cancer and Allied Diseases, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA; 3Departments of Pathology and Medicine, University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong, China; 4Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA; 5College of Public Health, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA; 6Departments of Pathology and Cancer Genetics, Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan; 7Department of Pathology, University of Oslo, Norwegian Radium Hospital, Oslo, Norway; 8Department of Pathology, Centre Hospitalier Lyon-Sud, Lyon, France; 9Department of Pathology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, Korea; 10Department of Pathology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore and 11Penn State Hershey Cancer Institute, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Hershey, PA, USA Natural killer (NK) cell lymphomas/leukemias are rare neo- Introduction plasms with an aggressive clinical behavior. -

Cells Tissue-Specific Education of Decidual NK

Tissue-Specific Education of Decidual NK Cells Andrew M. Sharkey, Shiqiu Xiong, Philippa R. Kennedy, Lucy Gardner, Lydia E. Farrell, Olympe Chazara, Martin A. This information is current as Ivarsson, Susan E. Hiby, Francesco Colucci and Ashley of September 29, 2021. Moffett J Immunol 2015; 195:3026-3032; Prepublished online 28 August 2015; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501229 Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/content/195/7/3026 Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2015/08/28/jimmunol.150122 Material 9.DCSupplemental http://www.jimmunol.org/ References This article cites 44 articles, 19 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/195/7/3026.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision by guest on September 29, 2021 • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2015 The Authors All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology Tissue-Specific Education of Decidual NK Cells Andrew M. Sharkey,*,†,1 Shiqiu Xiong,*,†,1 Philippa R. -

Fertilization & Implantation Systems

Spring 2020 – Systems Biology of Reproduction Discussion Outline – Fertilization & Implantation Systems Michael K. Skinner – Biol 475/575 CUE 418, 10:35-11:50 am, Tuesday & Thursday April 16, 2020 Week 14 Fertilization & Implantation Systems Primary Papers: 1. Teperek, et al. (2016) Genome Research 26:1034. 2. Brosens, et al. (2014) Scientific Reports 4:3894. 3. Vento-Tormo, et al. (2018) Nature 563(7731):347-353. Discussion Student 9: Reference 1 above • What was the experimental design and objectives? • What impact on the developing embryo was observed? • Can sperm epigenetic alterations modify the embryo? Student 10: Reference 2 above • How do abnormal embryos influence the endometrial cells? • What transcriptional influences were observed? • How do component embryos promote a supportive uterine environment? Student 11: Reference 3 above • What was the experimental design and technology? • What maternal-fetal interface interactions were identified? • What new insights for maternal-fetal interface were found to be critical for placentation and reproductive success? Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on March 30, 2018 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research Sperm is epigenetically programmed to regulate gene transcription in embryos Marta Teperek,1,2,6 Angela Simeone,1,2,6 Vincent Gaggioli,1,2 Kei Miyamoto,1,2 George E. Allen,1 Serap Erkek,3,4,7 Taejoon Kwon,5 Edward M. Marcotte,5 Philip Zegerman,1,2 Charles R. Bradshaw,1 Antoine H.F.M. Peters,3,4 John B. Gurdon,1,2 and Jerome Jullien1,2 1Wellcome Trust/Cancer Research