Final Report of Examiner, in Re Wonderwork, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Market Commentary 1 Utilities 7.26% 11.91% Front, We Are Very, Very Thankful to Have Been Able to Make So BRI Commentary 7

M A R K E T COMMENTARY QUARTERLY COMMENTARY VOLUME 9 ISSUE 4 JANUARY 2010 Authored by Howard J. “Rusty” Leonard, CFA CEO and Chief Investment Officer, Stewardship Partners Investment Counsel, Inc. STOCK S AND BOND S SOAR A S THE ECONOMY CONTINUE S TO HEAL “Give thanks to the Lord.. make known among the nations what he has done.” 1 Chronicles 16:8 (NIV) 009 was indisputably a great year for the financial markets even though it started in Chart 1 2the worst possible way. Equities, bonds and commodities all bounced strongly off their Massive Liquidity Injection Boosts Share Prices lows, significantly rewarding those investors who maintained their composure during the Nearly $3 Trillion to Support Markets Since 2008 global economy’s darkest hours. Stock prices were the main beneficiary of the recovery Strategas Liquidity Calculator, $ Billion with the S&P 500 advancing more than 70% from its March 2009 low and the MSCI 3000 World Index rising more than 75%. Bond prices also had dramatic price recoveries. The 2500 riskier the bond, the greater its recovery as investors celebrated the growing possibility they 2000 Liquidity Sources: Expanded Fed Balance Sheet would actually get their money back. Likewise, low quality stocks achieved the best returns 1500 Stimulus 1 & 2 TARP during 2009 as the ultimate fate of bankruptcy was avoided for many. Commodity prices Treasury MBS Purchases 1000 Fannie, Freddie Capital Injections also moved sharply higher as hopes of a global economic recovery began to be realized and FDIC as investors sought refuge in hard assets from spendthrift governments doing their best to 500 TLGP debase their currencies. -

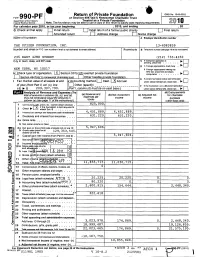

990 P^ Return of Private Foundation

990_P^ Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust ^O J 0 Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation 7 Internal Revenue service Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Pnr calendar year 2010 . or tax year beninninn . 2010. and endina . 20 G Check all that apply Initial return initial return of a former public charity Final return Amended return Address change Name change Name of foundation A Employer Identification number THE PFIZER FOUNDATION , INC. 13-6083839 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number (see page 10 of the instructions) 235 EAST 42ND STREET (212) 733-4250 City or town , state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is ► pending, check here D 1. Foreign organizations , check here ► NEW YORK, NY 10017 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach H Check typet e of org X Section 501 ( c 3 exempt private foundation g computation , , . , . ► Section 4947 ( a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method . Cash X Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here . ► of year (from Part ll, col (c), line ElOther (specify) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination 16) 20 9, 30 7, 7 90. -

Hru*Mry Ffiffi the S*Fikley Sauffdeftis Printrd Rsnthiy Ir' 8Ar{I*Ld, British Cnlu*Bi I, Canxd*, $Srsnd Clerr Lail R*Gi*Tr*Tisn Nu*Bar $*14

BAtrIKLEY ScfUNDEtrl // Ai..r O{STAL Jol..RtlAL FRCII{ BAlvf I hru*mry ffiffi The S*fiKLEY SAUffDEftis printrd rsnthiy ir' 8ar{i*ld, British Cnlu*bi I, Canxd*, $srsnd clerr lail r*gi*tr*tisn nu*bar $*14. F*st S${iue n{ c*iIing**Eer{ield, B.C. $ubsrriptIonr r&y be rrdered or rsnsl*&d by phoning qur Sa*field nulberr 7 ?st*32&7 or by *riting ta us TT"Ig Ssl9NKL€Y SSUhIT}€ft 8c*ct {? t. Elarnf ieldt. [|.t. V$Ft T,tsO $ubgcription prirae fcr lf$6r In Ss*{i*ld - *10.*0 far l? issuca *est nf f,*ntda * ff3,?0 for lt issurs 11,5.*. - *18.5* for 1? issus* $vsr*eee * f1*.50 {os' l? issues $vsrssxa friret 4Iass - *33"$0 :i *SVSSTISiMSHfiTEf, l,/fr p*ge , - f s.so 'r4$ " Sr l/{ pagn , . $12.ss *r . l/? p*ge " ttrg,$0 Full prg*, , f36.+CI Clarsified eds ar* FFI€E ! ! il r*il ;l 1l il I I / I ": TFE Iv{A$T}IEAD ' j€snn€r*r.?1, co-'editor Wetve Just retursed from a short trlp to l{isconsln to vlslt my folks, so the paper ls a few days leter than usual this rnonth" Next rnonrh'reril be back on.-Eamfield-Llige,whicb meanEcloger t+ the 5th then to the l0th, It was catrdln lYlsconsln,and ir snc"red three tlmeg while we rv€re there. I tend to forget .lus:: why thls part of censda ls nlcknarnedflotus landt Errtil I visit , spot rhere tJre snow keeps getting deeper and you have to remember t* sear yo$r cost.:vben ysu steF outslde. -

COMMUNITY CHURCH MORNING WORSHIP • 8:30 AM & 10:00 AM October 16, 2016 • 22Nd Sunday After Pentecost an Asterisk (*) Indicates When Those Who Are Able Will Stand

COMMUNITY CHURCH MORNING WORSHIP • 8:30 AM & 10:00 AM October 16, 2016 • 22nd Sunday after Pentecost An asterisk (*) indicates when those who are able will stand. CHIMING OF THE TRINITY A time to quiet our hearts, minds and voices in preparation for worship. Please fill out your prayer request cards at this time to be handed to the ushers later in the service. PRELUDE Fairest Lord Jesus arr. Eithun Roser Ringers SIGNING OF FRIENDSHIP REGISTER Please sign the Friendship Register with your name and address for our records of attendance and pass along to your pew mates. *CALL TO WORSHIP (Responsive) (Hebrews 4:12) The Word of God is living and active. We are so happy you are Sharper than any two-edged sword. worshiping with us today! It pierces until it divides soul from spirit, joints from marrow. If you have questions or need It judges our thoughts and the intentions of our hearts. any assistance, please see an Usher. *HYMN OF PRAISE Joyful, Joyful No. 20 *PRAYER OF PETITION (Unison) Assistance Hearing Devices Compassionate and loving God, since faith comes from hearing are available from an usher. Your Word, help us to truly listen to the scripture. May Your words To activate the LOOP HEARING convict us of our sins, console our hearts, and confirm our faith. We SYSTEM please turn your ask this in the Name of Jesus Christ, the Word made flesh. Amen. hearing aid to T-coil. GREETING ONE ANOTHER IN CHRISTIAN LOVE The Family Worship Viewing CALL TO PRAYER Holy, Holy, Holy (Argentina) arr. -

PQMD Program Brochure (PDF)

The Partnership for Quality Medical Donations www.pqmd.org www.cop.pqmd.org Five Pillars of PQMD 1. DONATION GUIDELINES The “PQMD Guidelines for Quality Medical Product Donations” are a set of guidelines for health supply and service donation across the globe. • Foundation of PQMD. • Influence and assure high standards of donations. • Updated annually and approved by board. 2. HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE Members donate and deliver hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of medical products and services each year for humanitarian assistance in the U.S. and around the world. • Coordination between and among members. • Assistance to most vulnerable communities. 3. DISASTER RESPONSE When a catastrophe strikes, members are among the first to respond with health-saving contributions, with short-term emergency aid to communities. • Initiate process of rebuilding healthcare infrastructures. • Address the complex logistics of any situation efficiently and effectively. • Ensure health needs of disaster-affected populations are quickly met. 4. HEALTH SYSTEMS STRENGTHENING Members are recognized as leaders in their industry or field of practice, making them optimally positioned to: • Advance service delivery, to disseminate health workforce information. • Develop, donate, and deliver medical products and technology to build resilience and empower communities. 5. KNOWLEDGE AND INNOVATION Members consistently share best practices in the medical donations field. Initiatives include: • Annual Global Health Policy Forums and Educational Forums. • Studies to better understand issues, activities, and trends regarding medical donations. • Online Community of Practice (CoP) to share knowledge, innovations, and best practices in the field. • Measuring for Success Initiative aimed at improving and standardizing the measurement and evaluation of medical donations, and establishing universal metrics for impact assessment. -

2017 Charity Listing

2017 Charity Listing Choose your cause and Show Some Love today. Zone 016 Oklahoma and North Texas ® www.oklahomanorthtexascfc.org TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................... 1 Goodwill Industries of Tulsa Inc ........................................................8 Hiv Resource Consortium Inc .............................................................8 LOCAL ORGANIZATIONS ............................ 7 Hospice of Green Country Inc ...........................................................8 Local Animal Charities of America ...................................................7 Life Senior Services Inc .........................................................................8 A New Leash on Life Inc .......................................................................7 Mental Health Association in Tulsa Inc...........................................8 Community Health Charities ..............................................................7 Okmulgee County Homeless Shelter Inc .......................................8 Allys House Inc .........................................................................................7 Okmulgee-Okfuskee County Youth Services Inc .......................8 Alzheimer’s Association, Oklahoma Chapter ...............................7 Operation Aware of Oklahoma Inc ..................................................8 Cerebral Palsy of Oklahoma Inc ........................................................7 Palmer Continuum of Care Inc ..........................................................8 -

Mercy Ships and Affiliates

MERCY SHIPS AND AFFILIATES Notes to Financial Statements FINANCIAL STATEMENTS With Independent Auditors’ Report December 31, 2014 and 2013 MERCY SHIPS Table of Contents Page Independent Auditors’ Report 1 Financial Statements Statements of Financial Position 3 Statements of Activities 4 Statements of Cash Flows 5 Notes to Consolidated and Combined Financial Statements 6 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT Board of Directors Mercy Ships and Affiliates Lindale, Texas We have audited the accompanying consolidated and combined financial statements of Mercy Ships and Affiliates, which comprise the consolidated and combined statements of financial position as of December 31, 2014 and 2013, and the related consolidated and combined statements of activities and cash flows for the years then ended, and the related notes to the consolidated and combined financial statements. Management’s Responsibility for the Consolidated and Combined Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these consolidated and combined financial statements in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of consolidated and combined financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Auditors’ Responsibility Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these consolidated and combined financial statements based on our audits. We conducted our audits in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audits to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the consolidated and combined financial statements are free from material misstatement. -

Reducing Healthcare Inequality

Reducing healthcare inequality Annual Report 2017 About the Philips Foundation The Philips Foundation is a registered charity that was established in July 2014 as the central platform for Philips’ CSR activities – founded on the belief that through innovation and collaboration we can solve some of the world’s toughest challenges and make an impact where it really matters. Reflecting our commitment to United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 3 (Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages) and 17 (Revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development), the mission of the Foundation is to reduce healthcare inequality by providing access to quality healthcare for disadvantaged communities. We do this by deploying Philips’ expertise, innovative products and solutions, by collaborating with key partners around the world (including respected NGOs such as UNICEF, Amref and ICRC), and by providing The Board of the Philips Foundation. From left to right: Herman Wijffels, Ronald de Jong, Mirjam van Reisen, Wim Leereveld financial support for the collaborative activities. www.philips-foundation.com Renewed focus and growing momentum Contents Welcome to the Philips Foundation Annual Report Further to this, we have intensified our partnership 2017. This year, Philips Foundation revised its with Ashoka, selecting social entrepreneurs who initial strategy in light of Royal Philips’ ongoing work on access to primary healthcare. Welcome from Ronald de Jong, Chairman of the Philips Foundation Board 3 transformation into a -

MERCY SHIPS and AFFILIATES Consolidated and Combined Financial Statements with Independent Auditors' Report December 31, 2018

MERCY SHIPS AND AFFILIATES Consolidated and Combined Financial Statements With Independent Auditors’ Report December 31, 2018 and 2017 MERCY SHIPS AND AFFILIATES Table of Contents Page Independent Auditors’ Report 1 Consolidated and Combined Financial Statements Consolidated and Combined Statements of Financial Position 3 Consolidated and Combined Statements of Activities 4 Consolidated and Combined Statement of Functional Expenses–2018 5 Consolidated and Combined Statement of Functional Expenses–2017 6 Consolidated and Combined Statements of Cash Flows 7 Notes to Consolidated and Combined Financial Statements 8 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT Board of Directors Mercy Ships and Affiliates Lindale, Texas Report on the Consolidated and Combined Financial Statements We have audited the accompanying consolidated and combined financial statements of Mercy Ships and Affiliates, which comprise the consolidated and combined statement of financial position as of December 31, 2018, and the related consolidated and combined statements of activities, functional expenses, and cash flows for the year then ended, and the related notes to the consolidated and combined financial statements. Management’s Responsibility for the Consolidated and Combined Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these consolidated and combined financial statements in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of consolidated and combined financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Auditors’ Responsibility Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these consolidated and combined financial statements based on our audits. We conducted our audits in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. -

Giving Guide

2021 Giving Guide making a difference together This giving guide provided thanks to our partner: Making a Dierence Together… Did You Your co-workers and fellow state employees collectively Know? making a difference together donated over $2.6 Million in 2020. Why? Let’s let them tell you! Dear Fellow State Employees, The SECC Is Greener already! Thanks to your generosity over the years, the SECC is a powerful force making a dierence! Since the campaign I support the SECC began, state employee donors like you have contributed more than $118 million to charities that make North Carolina a because in 2019 my sister I volunteer with the SECC better place for all of us. & I stayed at the SECU because I wish to spread Hospitality House in happiness, joy, & a helping In 2020 we were humbled by your generosity. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic this past year, employees across the state Winston Salem when our hand to those that need it. banded together to oer help in a tremendous time of need. mother was being treated at Thank you for ensuring our nonprofit charities continue to Baptist hospital. They were Ricky “Shane” Seeley Dept. of Public Safety The State Employees stay open, provide much needed services, and strengthen our a life saver for my family state and its communities. Combined Campaign during this dicult time. (SECC) is by and When you contribute to the SECC, your donation joins Becky Werts for North Carolina’s other state employee donations to become a more powerful, impactful gift. Together, these gifts create an incredible Dept. -

Sustainability Report

2018 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2018 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 04 A WORD FROM OUR PRESIDENT & CEO 06 INTRODUCTION TO THE MSC GROUP 10 MATERIALITY ASSESSMENT AND GOVERNANCE 16 SOCIAL INCLUSION 46 ENVIRONMENT OCCUPATIONAL 79 HEALTH & SAFETY BUSINESS ETHICS AND 97 PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS 120 ABOUT THIS REPORT A WORD FROM OUR PRESIDENT & CEO Throughout 2018, MSC further increased its efforts to Our activities and operations all over the world require promote sustainable and ethical business practices engagement with a wide range of stakeholders from within all entities of the Group, in line with its strategic most sectors and from both the public and private approach to sustainability and the Ten Principles of the spheres. Therefore, in our 2018 Sustainability Report, we United Nations Global Compact in the areas of human describe sustainability considerations from a variety of rights, labour, environment, and anti-corruption. perspectives, including those of the asset management and investor community, by underlining the interrela- In addition to responding to the evolving and strict- tion among all our strategic Sustainability Pillars and er complex maritime regulatory framework we must our continuous focus on Environmental, Social, and comply with as an international shipping company, Governance (ESG) factors. We also report on the way we continued adding layers to our existing internal in which we continue to address our sector’s trends methodologies and monitoring mechanisms in terms and global development challenges along with cross- of governance, compliance, and risk management. cutting human rights principles and considerations in Given the nature of our business activities and the our investment models to ensure long-term benefits in growth of our diversified value and supply chains, we local communities and to minimise our impact on the are making additional investments to ensure the effec- environment. -

Annual Report

2019 Annual Report All hands on deck Who is Mercy Ships Mercy Ships is a faith-based international development Globally, five billion organization that deploys hospital ships to some of the poorest countries in the world, delivering vital, free people have no access healthcare to people in desperate need. to safe and affordable Mercy Ships works closely with each host nation to improve the way healthcare is delivered across the surgery when they country through medical capacity building programs — training and mentoring local medical staff and need it. renovating hospitals and clinics for use after Mercy Ships complete our field service. Since 1978... Mercy Ships has worked in more than 56 countries, providing services valued at over $1.6 billion that have directly benefited more than 2.8 million people. We have also trained 44,300 local professionals in their areas of expertise to leave a legacy that lasts. Mission Impact Mercy Ships follows the 2,000-year-old model of In 1990, Mercy Ships turned Jesus, bringing hope and healing to the world’s attention to sub-Saharan Africa forgotten poor. where nearly 100% of the population lacks access to safe, Vision affordable, and timely surgery. Since then, Mercy Ships has Mercy Ships uses hospital ships to transform conducted 47 field services in 14 individuals and serve nations one at a time. African countries, most of which are ranked by the United Nations Values Development Index as the least developed in the world. Following the model of Jesus, we seek to: • Love God. • Love and serve others. • Be people of integrity.