Hekhsher Tzedek Al Pi Din

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Designing the Talmud: the Origins of the Printed Talmudic Page

Marvin J. Heller The author has published Printing the Talmud: A History of the Earliest Printed Editions of the Talmud. DESIGNING THE TALMUD: THE ORIGINS OF THE PRINTED TALMUDIC PAGE non-biblical Jewish work,i Its redaction was completed at the The Talmudbeginning is indisputablyof the fifth century the most and the important most important and influential commen- taries were written in the middle ages. Studied without interruption for a milennium and a half, it is surprising just how significant an eftèct the invention of printing, a relatively late occurrence, had upon the Talmud. The ramifications of Gutenberg's invention are well known. One of the consequences not foreseen by the early practitioners of the "Holy Work" and commonly associated with the Industrial Revolution, was the introduction of standardization. The spread of printing meant that distinct scribal styles became generic fonts, erratic spellngs became uni- form and sequential numbering of pages became standard. The first printed books (incunabula) were typeset copies of manu- scripts, lacking pagination and often not uniform. As a result, incunabu- la share many characteristics with manuscripts, such as leaving a blank space for the first letter or word to be embellshed with an ornamental woodcut, a colophon at the end of the work rather than a title page, and the use of signatures but no pagination.2 The Gutenberg Bibles, for example, were printed with blank spaces to be completed by calligra- phers, accounting for the varying appearance of the surviving Bibles. Hebrew books, too, shared many features with manuscripts; A. M. Habermann writes that "Conats type-faces were cast after his own handwriting, . -

J Ewish Community and Civic Commune In

Jewish community and civic commune in the high Middle Ages'' CHRISTOPH CLUSE 1. The following observations do not aim to provide a comprehensive phe nomenology of the J ewish community during the high and late medieval periods. Rather 1 wish to present the outlines of a model which describes the status of the Jewish community within the medieval town or city, and to ask how the concepts of >inclusion< and >exclusion< can serve to de scribe that status. Using a number of selected examples, almost exclusively drawn from the western regions of the medieval German empire, 1 will concentrate, first, on a comparison betweenJewish communities and other corporate bodies (>universitates<) during the high medieval period, and, secondly, on the means by which Jews and Jewish communities were included in the urban civic corporations of the later Middle Ages. To begin with, 1 should point out that the study of the medieval Jewish community and its various historical settings cannot draw on an overly rich tradition in German historical research. 1 The >general <historiography of towns and cities that originated in the nineteenth century accorded only sporadic attention to the J ews. Still, as early as 1866 the legal historian Otto Stobbe had paid attention to the relationship between the Jewish ::- The present article first appeared in a slightly longer German version entitled Die mittelalterliche jüdische Gemeinde als »Sondergemeinde« - eine Skizze. In: J OHANEK, Peter (ed. ): Sondergemeinden und Sonderbezirke in der Stadt der Vormoderne (Städteforschung, ser. A, vol. 52). Köln [et al.] 2005, pp. 29-51. Translations from the German research literature cited are my own. -

Melilah Agunah Sptib W Heads

Agunah and the Problem of Authority: Directions for Future Research Bernard S. Jackson Agunah Research Unit Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester [email protected] 1.0 History and Authority 1 2.0 Conditions 7 2.1 Conditions in Practice Documents and Halakhic Restrictions 7 2.2 The Palestinian Tradition on Conditions 8 2.3 The French Proposals of 1907 10 2.4 Modern Proposals for Conditions 12 3.0 Coercion 19 3.1 The Mishnah 19 3.2 The Issues 19 3.3 The talmudic sources 21 3.4 The Gaonim 24 3.5 The Rishonim 28 3.6 Conclusions on coercion of the moredet 34 4.0 Annulment 36 4.1 The talmudic cases 36 4.2 Post-talmudic developments 39 4.3 Annulment in takkanot hakahal 41 4.4 Kiddushe Ta’ut 48 4.5 Takkanot in Israel 56 5.0 Conclusions 57 5.1 Consensus 57 5.2 Other issues regarding sources of law 61 5.3 Interaction of Remedies 65 5.4 Towards a Solution 68 Appendix A: Divorce Procedures in Biblical Times 71 Appendix B: Secular Laws Inhibiting Civil Divorce in the Absence of a Get 72 References (Secondary Literature) 73 1.0 History and Authority 1.1 Not infrequently, the problem of agunah1 (I refer throughout to the victim of a recalcitrant, not a 1 The verb from which the noun agunah derives occurs once in the Hebrew Bible, of the situations of Ruth and Orpah. In Ruth 1:12-13, Naomi tells her widowed daughters-in-law to go home. -

Gemara Succah Elementary I and II

PREMIUMPREMIUM TORAHTORAH COLLEGECOLLEGE PROGRAMSPROGRAMSTaTa l l Gemara Succah Elementary I and II February 2019 Elementary Gemara I and II: Succah —Study Guide— In this Study Guide you will find: • Elementary Succah I: syllabus (page 4), and sample examination (page 11). • Elementary Succah II: syllabus (page 18), and sample examination (page 25). NOTE: a. Since you are required to answer in black ink, be sure to bring a black pen to your exam. b. Accustom yourself to outlining your answers on scrap paper and writing essays clearly. Illegible exams will not be graded. c. The lowest passing score on this exam is 70. You will not get credit for a score below 70, though in the case of a failed or illegible paper, you may be able to retake the exam after waiting six months. Grades for transcripts are calculated as follows: A = 90–100% B = 80–89% C = 70–79% This Study Guide is the property of TAL and MUST be returned after you take the exam. Failure to do so is an aveirah of gezel. GemaraSuccahElemIandIISPCombined-1 v02.indd © 2019 by Torah Accreditation Liaison. All Rights Reserved. Succah Elementary I and II Elementary Gemara I: Succah — Study Guide — This elementary Gemara I examination is based on the beginning of Maseches Succah, from: דף ד עמוד ב on (ושאינה גבוהה עשרה טפחים) 2a) until the two dots) דף ב עמוד א • (4b), and דף ז עמוד א 6b) through) דף ו עמוד ב on (ושאין לה שלש דפנות) from the two dots • .(on the last line גופא 7a) (until the word) In this Study Guide you will find: • The syllabus outline for the elementary Succah I examination (page 4). -

The Adjudication of Fines in Ashkenaz During the Medieval and Early Modern Periods and the Preservation of Communal Decorum

The Adjudication of Fines in Ashkenaz during the Medieval and Early Modern Periods and the Preservation of Communal Decorum Ephraim Kanarfogel* The Babylonian Talmud (Bava Qamma 84a–b) rules that fines and other assigned payments in situations where no direct monetary loss was incurred--or where the damages involved are not given to precise evaluation or compensation--can be adjudicated only in the Land of Israel, at a time when rabbinic judges were certified competent to do so by the unbroken authority of ordination (semikhah). In addition to the implications for the internal workings of the rabbinic courts during the medieval period and beyond, this ruling seriously impacted the maintaining of civility and discipline within the communities. Most if not all of the payments that a person who struck another is required to make according to Torah law fall into the category of fines or forms of compensation that are difficult to assess and thus could not be collected in the post-exilic Diaspora (ein danin dinei qenasot be-Bavel).1 * Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies, Yeshiva University. 1 See Arba’ah Turim, Ḥoshen Mishpat, sec. 1, and Beit Yosef, ad loc. In his no longer extant Sefer Avi’asaf, Eli’ezer b. Joel ha-Levi of Bonn (Rabiah, d. c. 1225) concludes that the victim of an assault can be awarded payments by a rabbinic court for the cost of his healing (rippui) and for money lost if he is unable to work (shevet), since these are more common types of monetary law, with more precisely assessed forms of compensation. -

Humor in Torah and Talmud

Sat 3 July 2010 Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Lunch and Learn Humor in Torah and Talmud -Not general presentation on Jewish humor, just humor in Tanach and Talmud, and list below is far from exhaustive -Tanach mentions “laughter” 50 times (root: tz-cho-q) [excluding Yitzhaq] -Some commentators say humor is not intentional. -Maybe sometimes, but one cannot avoid the feeling it is. -Reason for humor not always clear. -Rabbah (4th cent. Talmudist) always began his lectures with a joke: Before starting to teach, Rabbah joked and pupils laughed. Afterwards he started seriously teaching halachah. (Talmud, Shabbat 30b) Humor in Tanach -Sarai can’t conceive, so she tells her husband Abram: I beg you, go in to my maid [Hagar]; perhaps I can obtain children through her. And Abram listened to the voice of Sarai. [Genesis 16:2] Hagar gets pregnant and becomes very impertinent towards her mistress Sarai. So a very angry Sarai goes to her husband Abram and tells him: This is all your fault! [Genesis 16:5 ] -God tells Sarah she will have a child: And Sarah laughed, saying: Shall I have pleasure when I am old? My husband is also old. And the Lord said to Abraham [who did not hear Sarah]: “Why did Sarah laugh, saying: Shall I bear a child, when I am old?” [Genesis 18:12-13] God does not report all that Sarah said for shalom bayit -- to keep peace in the family. Based on this, Talmud concludes it’s OK to tell white lies [Bava Metzia 87a]. Note: After Sarah dies Abraham marries Keturah and has six more sons. -

What Sugyot Should an Educated Jew Know?

What Sugyot Should An Educated Jew Know? Jon A. Levisohn Updated: May, 2009 What are the Talmudic sugyot (topics or discussions) that every educated Jew ought to know, the most famous or significant Talmudic discussions? Beginning in the fall of 2008, about 25 responses to this question were collected: some formal Top Ten lists, many informal nominations, and some recommendations for further reading. Setting aside the recommendations for further reading, 82 sugyot were mentioned, with (only!) 16 of them duplicates, leaving 66 distinct nominated sugyot. This is hardly a Top Ten list; while twelve sugyot received multiple nominations, the methodology does not generate any confidence in a differentiation between these and the others. And the criteria clearly range widely, with the result that the nominees include both aggadic and halakhic sugyot, and sugyot chosen for their theological and ideological significance, their contemporary practical significance, or their centrality in discussions among commentators. Or in some cases, perhaps simply their idiosyncrasy. Presumably because of the way the question was framed, they are all sugyot in the Babylonian Talmud (although one response did point to texts in Sefer ha-Aggadah). Furthermore, the framing of the question tended to generate sugyot in the sense of specific texts, rather than sugyot in the sense of centrally important rabbinic concepts; in cases of the latter, the cited text is sometimes the locus classicus but sometimes just one of many. Consider, for example, mitzvot aseh she-ha-zeman gerama (time-bound positive mitzvoth, no. 38). The resulting list is quite obviously the product of a committee, via a process of addition without subtraction or prioritization. -

Defining Purity and Impurity Parshat Sh’Mini, Leviticus 6:1- 11:47| by Mark Greenspan “The Dietary Laws” by Rabbi Paul S

Defining Purity and Impurity Parshat Sh’mini, Leviticus 6:1- 11:47| by Mark Greenspan “The Dietary Laws” by Rabbi Paul S. Drazen, (pp.305-338) in The Observant Life Introduction A few weeks before Passover reports came in from the Middle East that a cloud of locust had descended upon Egypt mimicking the eighth plague of the Bible. When the wind shifted direction the plague of locust crossed over the border into Israel. There was great excitement in Israel when some rabbis announced that the species of locust that had invaded Israel were actually kosher! Offering various recipes Rabbi Natan Slifkin announced that there was no reason that Jews could not adopt the North African custom of eating the locust. Slifkin wrote: “I have eaten locusts on several occasions. They do not require a special form of slaughter and one usually kills them by dropping them into boiling water. They can be cooked in a variety of ways – lacking any particular culinary skills I usually just fry them with oil and some spices. It’s not the taste that is distinctive so much as the tactile experience of eating a bug – crunchy on the outside with a chewy center!” Our first reaction to the rabbi’s announcement is “Yuck!” Yet his point is well taken. While we might have a cultural aversion to locusts there is nothing specifically un-Jewish about eating them. The Torah speaks of purity and impurity with regard to food. Kashrut has little to do with hygiene, health, or culinary tastes. We are left to wonder what makes certain foods tamei and others tahor? What do we mean when we speak about purity with regard to kashrut? The Torah Connection These are the instructions (torah) concerning animals, birds, all living creatures that move in water and all creatures that swarm on earth, for distinguishing between the impure (tamei) and the pure (tahor), between living things that may be eaten and the living things that may not be eaten. -

The History of the Jews

TH E H I STO RY O F TH E JEWS B Y fid t t at h menta l J B E 39 . b ) , iBb PROFES S OR WI H I T RY AND LI T RAT RE OF J E S H S O E U , B RE I LL G I I ATI W C C C o. HE UN ON O E E, N NN , S ECOND EDI TI ON Revised a nd E n la rged NEW YORK BLOCH PUBLI SHING COMPANY “ ” TH E J EWI SH B OOK CONCERN PYRI G T 1 1 0 1 2 1 CO H , 9 , 9 , B LOCH PUBLISHI NG COM PANY P re ss o f % i J . J L t t l e I m . 86 ve s Co p a n y w rk Y U . S . Ne . o , A TAB LE OF CONTENTS CH APTE R PAGE R M TH E AB YL I A APTI VI TY 86 B C To I . F O B ON N C , 5 , TH E TR CTI TH E EC D M PL DES U ON OF S ON TE E, 0 7 C E . R M TH E TR CTI R AL M 0 TO II . F O DES U ON OF JE US E , 7 , TH E MPL TI TH E I A CO E ON OF M SH N H , II - I . ERA TH E ALM D 200 600 OF T U , Religiou s Histo ry o f t h e Era IV. R M TH E I LA M 622 TO TH E ERA F O R SE OF IS , , OF TH E R AD 1 0 6 C US ES , 9 Literary Activity o f t h e P erio d - V. -

An Exploration of the Challenges and Possibilities of Local Kosher Meat in the Jewish Community of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Environmental Studies Electronic Thesis Collection Undergraduate Theses 2016 Kosher, Local, Organic, Oh My! An exploration of the challenges and possibilities of local kosher meat in the Jewish Community of Vermont. Frances Lasday Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uvm.edu/envstheses Recommended Citation Lasday, Frances, "Kosher, Local, Organic, Oh My! An exploration of the challenges and possibilities of local kosher meat in the Jewish Community of Vermont." (2016). Environmental Studies Electronic Thesis Collection. Paper 39. This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Environmental Studies Electronic Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kosher, Local, Organic, Oh My! An exploration of the challenges and possibilities of local kosher meat in the Jewish Community of Vermont. Frances Lasday A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Environmental Program University of Vermont May 2016 Advisors: Katherine Anderson, Ph. D, Environmental Program Susan Leff, Executive Director, Jewish Communities of Vermont Abstract The laws of kashrut delineate the Jewish dietary practice and prohibitions. Certified kosher food is readily found in super markets across the world, despite the fact that Jews account for only .2% of the world’s population, and 1.4% of the US population. Processed kosher food is easily accessible in the United States, but kosher meat is scarce in regions where there are smaller Jewish communities such as Vermont. -

Humor in Talmud and Midrash

Tue 14, 21, 28 Apr 2015 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Jewish Community Center of Northern Virginia Adult Learning Institute Jewish Humor Through the Sages Contents Introduction Warning Humor in Tanach Humor in Talmud and Midrash Desire for accuracy Humor in the phrasing The A-Fortiori argument Stories of the rabbis Not for ladies The Jewish Sherlock Holmes Checks and balances Trying to fault the Torah Fervor Dreams Lying How many infractions? Conclusion Introduction -Not general presentation on Jewish humor: Just humor in Tanach, Talmud, Midrash, and other ancient Jewish sources. -Far from exhaustive. -Tanach mentions “laughter” 50 times (root: tz-cho-q) [excluding Yitzhaq] -Talmud: Records teachings of more than 1,000 rabbis spanning 7 centuries (2nd BCE to 5th CE). Basis of all Jewish law. -Savoraim improved style in 6th-7th centuries CE. -Rabbis dream up hypothetical situations that are strange, farfetched, improbable, or even impossible. -To illustrate legal issues, entertain to make study less boring, and sharpen the mind with brainteasers. 1 -Going to extremes helps to understand difficult concepts. (E.g., Einstein's “thought experiments”.) -Some commentators say humor is not intentional: -Maybe sometimes, but one cannot avoid the feeling it is. -Reason for humor not always clear. -Rabbah (4th century CE) always began his lectures with a joke: Before he began his lecture to the scholars, [Rabbah] used to say something funny, and the scholars were cheered. After that, he sat in awe and began the lecture. [Shabbat 30b] -Laughing and entertaining are important. Talmud: -Rabbi Beroka Hoza'ah often went to the marketplace at Be Lapat, where [the prophet] Elijah often appeared to him. -

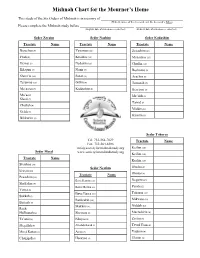

English Mishnah Chart

Mishnah Chart for the Mourner’s Home This study of the Six Orders of Mishnah is in memory of (Hebrew names of the deceased, and the deceased’s father) Please complete the Mishnah study before (English date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) (Hebrew date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) Seder Zeraim Seder Nashim Seder Kodashim Tractate Name Tractate Name Tractate Name Berachos (9) Yevamos (16) Zevachim (14) Peah (8) Kesubos (13) Menachos (13) Demai (7) Nedarim (11) Chullin (12) Kilayim (9) Nazir (9) Bechoros (9) Shevi’is (10) Sotah (9) Arachin (9) Terumos (11) Gittin (9) Temurah (7) Ma’asros (5) Kiddushin (4) Kereisos (6) Ma’aser Me’ilah (6) Sheni (5) Tamid (7) Challah (4) Middos (5) Orlah (3) Kinnim (3) Bikkurim (3) Seder Tohoros Tel: 732-364-7029 Tractate Name Fax: 732-364-8386 [email protected] Keilim (10) Seder Moed www.societyformishnahstudy.org Keilim (10) Tractate Name Keilim (10) Shabbos (24) Seder Nezikin Oholos (9) Eruvin (10) Tractate Name Oholos (9) Pesachim (10) Bava Kamma (10) Negaim (14) Shekalim (8) Bava Metzia (10) Parah (12) Yoma (8) Bava Basra (10) Tohoros (10) Sukkah (5) Sanhedrin (11) Mikvaos (10) Beitzah (5) Makkos (3) Niddah (10) Rosh HaShanah (4) Shevuos (8) Machshirin (6) Ta’anis (4) Eduyos (8) Zavim (5) Megillah (4) Avodah Zarah (5) Tevul Yom (4) Moed Kattan (3) Avos (5) Yadaim (4) Chagigah (3) Horayos (3) Uktzin (3) • Our Sages have said that Asher, son of the Patriarch Jacob sits at the opening to Gehinom (Purgatory), and saves [from entering therein] anyone on whose behalf Mishnah is being studied .