Issue Discussion in the Georgia Senate Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 2, 2021 the Honorable Michael Khouri Chairman Federal Maritime

March 2, 2021 The Honorable Michael Khouri Chairman Federal Maritime Commission 800 North Capitol Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20573 Dear Chairman Khouri, We write to express concern with the reported practices of certain vessel-operating common carriers (VOCCs) related to the denial of carriage for agricultural commodities. If the reports are true, such practices would be unreasonable and would hurt millions of producers across the nation by preventing them from competing in overseas markets. We support the Federal Maritime Commission’s current efforts to investigate these reports, and call on the Commission to quickly resolve this critical issue. As you know, ports across the United States are experiencing unprecedented congestion and record container volumes, which alone pose significant challenges for agricultural exporters seeking to deliver their products affordably and dependably to foreign markets. In the midst of this challenge, reports that certain VOCCs are returning to their origin with empty containers rather than accepting U.S. agriculture and forestry exports not only greatly exacerbates the problem, but potentially violates the Shipping Act as an unjust and unreasonable practice.1 We understand that the Commission in March 2020 initiated Fact Finding No. 29 – led by Commissioner Rebecca Dye – which was expanded in November 2020 to investigate reports of potentially unjust and unreasonable practices by certain VOCCs discussed above. We support this investigative effort, and – in the event that unjust or unreasonable practices by certain VOCCs are discovered – urge the Commission to take appropriate enforcement actions under the Shipping Act to put an end to such practices. The need is urgent, especially with record container volumes at the nation’s major ports. -

James.Qxp March Apri

COBB COUNTY A BUSTLING MARCH/APRIL 2017 PAGE 26 AN INSIDE VIEW INTO GEORGIA’S NEWS, POLITICS & CULTURE THE 2017 MOST INFLUENTIAL GEORGIA LOTTERY CORP. CEO ISSUE DEBBIE ALFORD COLUMNS BY KADE CULLEFER KAREN BREMER MAC McGREW CINDY MORLEY GARY REESE DANA RICKMAN LARRY WALKER The hallmark of the GWCCA Campus is CONNEE CTIVITY DEPARTMENTS Publisher’s Message 4 Floating Boats 6 FEATURES James’ 2017 Most Influential 8 JAMES 18 Saluting the James 2016 “Influentials” P.O. BOX 724787 ATLANTA, GEORGIA 31139 24 678 • 460 • 5410 Georgian of the Year, Debbie Alford Building A Proposed Contiguous Exhibition Facilityc Development on the Rise in Cobb County 26 PUBLISHED BY by Cindy Morley INTERNET NEWS AGENCY LLC 2017 Legislators of the Year 29 Building B CHAIRMAN MATTHEW TOWERY COLUMNS CEO & PUBLISHER PHIL KENT Future Conventtion Hotel [email protected] Language Matters: Building C How We Talk About Georgia Schools 21 CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER LOUIE HUNTER by Dr. Dana Rickman ASSOCIATE EDITOR GARY REESE ADVERTISING OPPORTUNITIES Georgia’s Legal Environment on a PATTI PEACH [email protected] Consistent Downward Trend 23 by Kade Cullefer The connections between Georggia World Congress Center venues, the hotel MARKETING DIRECTOR MELANIE DOBBINS district, and the world’world s busiest aairporirport are key differentiaferentiatorsators in Atlanta’Atlanta’s ability to [email protected] Georgia Restaurants Deliver compete for in-demand conventions and tradeshows. CIRCULATION PATRICK HICKEY [email protected] Significant Economic Impact 31 by Karen Bremer CONTRIBUTING WRITERS A fixed gateway between the exhibit halls in Buildings B & C would solidify KADE CULLEFER 33 Atlanta’s place as the world’s premier convention destination. -

Presidential Results on November 7, 2020, Several Media Organizations

Presidential Results On November 7, 2020, several media organizations declared that Joseph Biden and Kamala Harris won the election for the President and Vice President of the United States. Biden and Harris will take office on January 20, 2021. Currently, President-elect Biden is leading in the electoral college and popular vote. Votes are still being counted so final electoral college and popular vote counts are not available. NASTAD will provide transition documents to the incoming Administration, highlighting agency-specific recommendations that pertain to health department HIV and hepatitis programs. Additionally, the Federal AIDS Policy Partnership (FAPP) and the Hepatitis Appropriations Partnership (HAP), two coalitions that NASTAD leads, will also submit transition documents stressing actions the next Administration can take relating to the HIV and hepatitis epidemics, respectively. House and Senate Results Several House races are still undecided, but Democrats have kept control of the chamber. Republicans picked up several House districts but did not net the 17 seats they needed to gain the majority. Control of the Senate is still unknown with two uncalled seats (Alaska and North Carolina) and two runoffs in Georgia. The runoff races in Georgia will take place on January 5, 2021, so the Senate make up will not be final until then. While it remains likely that Republicans will remain in control of the Senate, if Democrats win both run off races, they will gain control of the Senate with Vice- President-elect Harris serving as tiebreaker. Pre- Post- Party election election Democrats 45 46 Senate*** Republicans 53 50 Independent 2* 2** Democrats 232 219 House**** Republicans 197 203 Independent 0 0 * Angus King (ME) and Bernie Sanders (VT) caucused with the Democrats. -

District Policy Group Provides Top-Line Outcomes and Insight, with Emphasis on Health Care Policy and Appropriations, Regarding Tuesday’S Midterm Elections

District Policy Group provides top-line outcomes and insight, with emphasis on health care policy and appropriations, regarding Tuesday’s midterm elections. Election Outcome and Impact on Outlook for 114th Congress: With the conclusion of Tuesday’s midterm elections, we have officially entered that Lame Duck period of time between the end of one Congress and the start of another. Yesterday’s results brought with them outcomes that were both surprising and those that were long-anticipated. For the next two years, the House and Senate will be controlled by the Republicans. However, regardless of the predictions that pundits made, the votes are in, Members of the 114th Congress (2015-2016) have been determined, and we can now begin to speculate about what these changes will mean for business interests and advocacy organizations. Even though we now have a Republican majority in Congress, for the next two years, President Obama remains resident at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Although President Obama will be a Lame Duck President, he still has issues and priority policies he wishes to pursue. Many other Lame Duck presidents have faced Congresses controlled by the opposite party and how a President responds to the challenge often can determine his legacy. Given the total number of Republican pick-ups in the House and Senate, we anticipate the GOP will feel emboldened to pursue its top policy priorities; as such, we do not suspect that collaboration and bipartisanship will suddenly arrive at the Capitol. We anticipate the Democrats will work hard to try to keep their caucus together, but this may prove challenging for Senate Minority Leader Reid, especially with the moderate Democrats and Independents possibly deciding to ally with the GOP. -

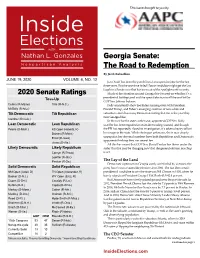

June 19, 2020 Volume 4, No

This issue brought to you by Georgia Senate: The Road to Redemption By Jacob Rubashkin JUNE 19, 2020 VOLUME 4, NO. 12 Jon Ossoff has been the punchline of an expensive joke for the last three years. But the one-time failed House candidate might get the last laugh in a Senate race that has been out of the spotlight until recently. 2020 Senate Ratings Much of the attention around Georgia has focused on whether it’s a Toss-Up presidential battleground and the special election to fill the seat left by GOP Sen. Johnny Isakson. Collins (R-Maine) Tillis (R-N.C.) Polls consistently show Joe Biden running even with President McSally (R-Ariz.) Donald Trump, and Biden’s emerging coalition of non-white and Tilt Democratic Tilt Republican suburban voters has many Democrats feeling that this is the year they turn Georgia blue. Gardner (R-Colo.) In the race for the state’s other seat, appointed-GOP Sen. Kelly Lean Democratic Lean Republican Loeffler has been engulfed in an insider trading scandal, and though Peters (D-Mich.) KS Open (Roberts, R) the FBI has reportedly closed its investigation, it’s taken a heavy toll on Daines (R-Mont.) her image in the state. While she began unknown, she is now deeply Ernst (R-Iowa) unpopular; her abysmal numbers have both Republican and Democratic opponents thinking they can unseat her. Jones (D-Ala.) All this has meant that GOP Sen. David Perdue has flown under the Likely Democratic Likely Republican radar. But that may be changing now that the general election matchup Cornyn (R-Texas) is set. -

Untitled Spreadsheet

Advertising Information Member State Ad 1 Ad 2 Ad 3 Ad 4 Ad 5 Ad 6 https://www.youtube.com/watch? https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=9WcNndBISw4&ab_channel=EndCitizen v=2moiC05yntw&ab_channel=EndCitizens S.1 Bob Casey Pennsylvania sUnited United https://www.youtube.com/watch? https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=jpR1QsUjtuw&ab_channel=EndCitizens v=_fuqLjm- Digital Raphael Warnock Georgia United _KA&ab_channel=EndCitizensUnited https://www.youtube.com/watch? https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=JIbTcvCj5u4&ab_channel=EndCitizensU v=1bdD47oTM9E&ab_channel=EndCitizen Running March 18-April 30 Jon Ossoff Georgia nited sUnited https://www.youtube.com/watch? https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=mn2md4LGTAs&ab_channel=EndCitizen v=zcYK4bW2- $1.2 million Angus King Maine sUnited v4&ab_channel=EndCitizensUnited https://www.youtube.com/watch? https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=XW5TtsTGcCg&ab_channel=EndCitizens v=Gwac2mhKA0g&ab_channel=EndCitizen Mark Kelly Arizona United sUnited https://www.youtube.com/watch? https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=R_O8ObieJmY&ab_channel=EndCitizens v=BrlzXDUzVYQ&ab_channel=EndCitizens Kyrsten Sinema Arizona United United https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=- https://www.youtube.com/watch? https://www.youtube.com/watch? https://www.youtube.com/watch? 5LU352MEz8&ab_channel=EndCitizensU v=srOQEyaBTnI&ab_channel=EndCitizens v=02Szc2pZ7Ng&feature=youtu. v=3LBV4PdGZj8&ab_channel=EndCitizensUni Susan Collins Maine nited United be&ab_channel=EndCitizensUnited ted https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=- https://www.youtube.com/watch? https://www.youtube.com/watch? https://www.youtube.com/watch? 5LU352MEz8&ab_channel=EndCitizensU v=srOQEyaBTnI&ab_channel=EndCitizens v=02Szc2pZ7Ng&feature=youtu. v=3LBV4PdGZj8&ab_channel=EndCitizensUni Pat Toomey Pennsylvania nited United be&ab_channel=EndCitizensUnited ted https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=- https://www.youtube.com/watch? https://www.youtube.com/watch? https://www.youtube.com/watch? 5LU352MEz8&ab_channel=EndCitizensU v=srOQEyaBTnI&ab_channel=EndCitizens v=02Szc2pZ7Ng&feature=youtu. -

Talking About Climate Change in the Georgia U.S. Senate Races

Talking About Climate In The Georgia U.S. Senate Races Why Georgia Voters Need To Hear About Climate Download this research in MS Word format here: https://drive.google.com/open?id=17hKqDq_dnSwv2o9Shxhj2XaRBykq5sMZ CONTENTS TL/DR: ................................................................. ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. CONTENTS .................................................................................................................... 1 WHY CLIMATE ACTION IS A WINNING ISSUE IN GEORGIA ..................................... 2 CANDIDATE BACKGROUNDS ...................................................................................... 3 CLIMATE CHANGE TOUCHES EVERY ISSUE IN 2020 ................................................. 5 CONFRONTING THE CRISIS ........................................................................................ 9 GLOBAL LEADERSHIP ................................................................................................ 13 CLEAN ENERGY JOBS ................................................................................................. 16 COST OF DOING NOTHING ......................................................................................... 19 Climate Power 2020 Talking About Climate In The Georgia U.S. Senate Races 1 WHY CLIMATE ACTION IS A WINNING ISSUE IN GEORGIA The politics of climate have changed and embracing bold climate action is a winning message. Climate change is a defining issue for key voting blocs – younger voters, voters of color, and suburban women strongly believe -

GUIDE to the 117Th CONGRESS

GUIDE TO THE 117th CONGRESS Table of Contents Health Professionals Serving in the 117th Congress ................................................................ 2 Congressional Schedule ......................................................................................................... 3 Office of Personnel Management (OPM) 2021 Federal Holidays ............................................. 4 Senate Balance of Power ....................................................................................................... 5 Senate Leadership ................................................................................................................. 6 Senate Committee Leadership ............................................................................................... 7 Senate Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................. 8 House Balance of Power ...................................................................................................... 11 House Committee Leadership .............................................................................................. 12 House Leadership ................................................................................................................ 13 House Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................ 14 Caucus Leadership and Membership .................................................................................... 18 New Members of the 117th -

View Full PDF Newsletter

ForestGeorgia ForestWatch Quarterly NewsletterNews Winter 2020 Bartram Series Challenge partnership hike February, 2020 Inside This Issue From the Director ...................... 2 Book Review – Eager: Thank You, Forest Guardians! ......7 The Surprising, Secret Life of Around the Forest ..................... 3 Beavers and Why They Matter ............5 Donor Spotlight: Bob Kibler ........8 The Biggest Threat Yet to Foothills Landscape Project Update ....6 2019 Supporters – Our Most Important Thank You! ................................10 Environmental Law .................... 4 Welcome New Members! ...................7 Jess Riddle From the Director Executive Director In public conflicts, the side that cares the most usually wins. Over about. Less technical help such as sealing envelopes and making the past few months, I have been amazed time and again by how donations keep ForestWatch going and focused on the issues that much the Georgia ForestWatch community cares about our forests. impact the forest. ForestWatch volunteers have shown their dedication by wading And we are not alone. Other groups like the Chattahoochee Trail through bureaucratic documents on the Foothills Landscape Project Horse Association sent out alerts about Foothills and weighed in and then diving into the scientific references cited within to see with their own comments. Our partners add to our abilities; for where the research does and does not support the Forest Service’s example, the Southern Environmental Law Center helping us with claims. Volunteers have also gone into the field to collect hard data the finer points of the Forest Service’s legal obligations. on potential impacts of future projects and actual impacts of past projects, which provides a better basis for evaluating projects and It’s easy for someone who cares about the environment to pick up making decisions. -

State Delegations

STATE DELEGATIONS Number before names designates Congressional district. Senate Republicans in roman; Senate Democrats in italic; Senate Independents in SMALL CAPS; House Democrats in roman; House Republicans in italic; House Libertarians in SMALL CAPS; Resident Commissioner and Delegates in boldface. ALABAMA SENATORS 3. Mike Rogers Richard C. Shelby 4. Robert B. Aderholt Doug Jones 5. Mo Brooks REPRESENTATIVES 6. Gary J. Palmer [Democrat 1, Republicans 6] 7. Terri A. Sewell 1. Bradley Byrne 2. Martha Roby ALASKA SENATORS REPRESENTATIVE Lisa Murkowski [Republican 1] Dan Sullivan At Large – Don Young ARIZONA SENATORS 3. Rau´l M. Grijalva Kyrsten Sinema 4. Paul A. Gosar Martha McSally 5. Andy Biggs REPRESENTATIVES 6. David Schweikert [Democrats 5, Republicans 4] 7. Ruben Gallego 1. Tom O’Halleran 8. Debbie Lesko 2. Ann Kirkpatrick 9. Greg Stanton ARKANSAS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES John Boozman [Republicans 4] Tom Cotton 1. Eric A. ‘‘Rick’’ Crawford 2. J. French Hill 3. Steve Womack 4. Bruce Westerman CALIFORNIA SENATORS 1. Doug LaMalfa Dianne Feinstein 2. Jared Huffman Kamala D. Harris 3. John Garamendi 4. Tom McClintock REPRESENTATIVES 5. Mike Thompson [Democrats 45, Republicans 7, 6. Doris O. Matsui Vacant 1] 7. Ami Bera 309 310 Congressional Directory 8. Paul Cook 31. Pete Aguilar 9. Jerry McNerney 32. Grace F. Napolitano 10. Josh Harder 33. Ted Lieu 11. Mark DeSaulnier 34. Jimmy Gomez 12. Nancy Pelosi 35. Norma J. Torres 13. Barbara Lee 36. Raul Ruiz 14. Jackie Speier 37. Karen Bass 15. Eric Swalwell 38. Linda T. Sa´nchez 16. Jim Costa 39. Gilbert Ray Cisneros, Jr. 17. Ro Khanna 40. Lucille Roybal-Allard 18. -

Governmental Directory

GOVERNMENTAL DIRECTORY GOVERNOR'S OFFICE (404)656-1776 GEORGIA SENATE 1-800-282-5803 GEORGIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STATE INFORMATION (404)656-2000 (404)656-5015 FEDERAL INFORMATION 1-800-688-9889 GOVERNOR: 4 Year Terms www.gov.georgia.gov Brian Kemp (R) Term Expires 12/31/2022 206 Washington St. 111 State Capitol; Atlanta, GA 30334 (404) 656-1776 (O); (404)657-7332 (F) SECRETARY OF STATE: www.sos.ga.gov Brad Raffensperger (R) Term Expires 12/31/2022 214 State Capitol; Atlanta, GA 30334 (844) 753-7825 (O); (404)656-0513 (F) Email: [email protected] U.S. SENATE: 6 Year Terms www.senate.gov David Perdue (R) Term Expires 12/31/2020 455 Russell Senate Office Bldg; Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-3521 (O); (202) 228-1031 (F) 3280 Peachtree St. NE, Ste 2640, Atlanta, GA 30305 (404)865-0087 (O); (404) 949-0912 (F) Website: http://perdue.senate.gov Kelly Loeffler (R) Term Expires 12/31/2020 B85 Russell Senate Office Bldg; Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-3643 (O); (202) 228-0724 (F) 3625 Cumberland Blvd; Suite 970; Atlanta, GA 30339 (770) 661-0999 (O); (770) 661-0768 (F) Website: http://isakson.senate.gov U.S. REPRESENTATIVE: 2 Year Term www.house.ga.gov 1st U.S. Congressional District Buddy Carter (R) Term Expires 12/31/2020 432 Cannon House Office Bldg; Washington, DC 20515 (202) 225-5831 (O); (202) 226-2269 (F) 6602 Abercorn St; Suite 105B Savannah, GA 31405 ;(912)352-0101(O) ;(912)352-0105(F) Website: http://buddycarter.house.gov GEORGIA SENATE: 2 Year Terms www.senate.ga.gov 1st District Ben Watson (R): Term Expires 12/31/2020 320–B Coverdell -

Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress

Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress AGRICULTURE, NUTRITION AND FORESTRY BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Pat Roberts, Kansas Debbie Stabenow, Michigan Mike Crapo, Idaho Sherrod Brown, Ohio Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont Richard Shelby, Alabama Jack Reed, Rhode Island Mitch McConnell, Kentucky Sherrod Brown, Ohio Bob Corker, Tennessee Bob Menendez, New Jersey John Boozman, Arkansas Amy Klobuchar, Minnesota Pat Toomey, Pennsylvania Jon Tester, Montana John Hoeven, North Dakota Michael Bennet, Colorado Dean Heller, Nevada Mark Warner, Virginia Joni Ernst, Iowa Kirsten Gillibrand, New York Tim Scott, South Carolina Elizabeth Warren, Massachusetts Chuck Grassley, Iowa Joe Donnelly, Indiana Ben Sasse, Nebraska Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota John Thune, South Dakota Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota Tom Cotton, Arkansas Joe Donnelly, Indiana Steve Daines, Montana Bob Casey, Pennsylvania Mike Rounds, South Dakota Brian Schatz, Hawaii David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland Luther Strange, Alabama Thom Tillis, North Carolina Catherine Cortez Masto, Nevada APPROPRIATIONS John Kennedy, Louisiana REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC BUDGET Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Mitch McConnell, Patty Murray, Kentucky Washington Mike Enzi, Wyoming Bernie Sanders, Vermont Richard Shelby, Dianne Feinstein, Alabama California Chuck Grassley, Iowa Patty Murray,