Remarks by Mary Banotti for the Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (515Kb)

European Community No. 26/1984 July 10, 1984 Contact: Ella Krucoff (202) 862-9540 THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT: 1984 ELECTION RESULTS :The newly elected European Parliament - the second to be chosen directly by European voters -- began its five-year term last month with an inaugural session in Strasbourg~ France. The Parliament elected Pierre Pflimlin, a French Christian Democrat, as its new president. Pflimlin, a parliamentarian since 1979, is a former Prime Minister of France and ex-mayor of Strasbourg. Be succeeds Pieter Dankert, a Dutch Socialist, who came in second in the presidential vote this time around. The new assembly quickly exercised one of its major powers -- final say over the European Community budget -- by blocking payment of a L983 budget rebate to the United Kingdom. The rebate had been approved by Community leaders as part of an overall plan to resolve the E.C.'s financial problems. The Parliament froze the rebate after the U.K. opposed a plan for covering a 1984 budget shortfall during a July Council of Ministers meeting. The issue will be discussed again in September by E.C. institutions. Garret FitzGerald, Prime Minister of Ireland, outlined for the Parliament the goals of Ireland's six-month presidency of the E.C. Council. Be urged the representatives to continue working for a more unified Europe in which "free movement of people and goods" is a reality, and he called for more "intensified common action" to fight unemployment. Be said European politicians must work to bolster the public's faith in the E.C., noting that budget problems and inter-governmental "wrangles" have overshadolted the Community's benefits. -

Papers of Gemma Hussey P179 Ucd Archives

PAPERS OF GEMMA HUSSEY P179 UCD ARCHIVES [email protected] www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 © 2016 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii CONTENTS CONTEXT Biographical History iv Archival History vi CONTENT AND STRUCTURE Scope and Content vii System of Arrangement ix CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE Access xi Language xi Finding Aid xi DESCRIPTION CONTROL Archivist’s Note xi ALLIED MATERIALS Allied Collections in UCD Archives xi Published Material xi iii CONTEXT Biographical History Gemma Hussey nee Moran was born on 11 November 1938. She grew up in Bray, Co. Wicklow and was educated at the local Loreto school and by the Sacred Heart nuns in Mount Anville, Goatstown, Co. Dublin. She obtained an arts degree from University College Dublin and went on to run a successful language school along with her business partner Maureen Concannon from 1963 to 1974. She is married to Dermot (Derry) Hussey and has one son and two daughters. Gemma Hussey has a strong interest in arts and culture and in 1974 she was appointed to the board of the Abbey Theatre serving as a director until 1978. As a director Gemma Hussey was involved in the development of policy for the theatre as well as attending performances and reviewing scripts submitted by playwrights. In 1977 she became one of the directors of TEAM, (the Irish Theatre in Education Group) an initiative that emerged from the Young Abbey in September 1975 and founded by Joe Dowling. It was aimed at bringing theatre and theatre performance into the lives of children and young adults. -

Here Family, Community and the Economy Can Prosper Together

To the Lord Mayor and Report No. 161/2010 Members of Dublin City Council Report of the Dublin City Manager Annual Report and Accounts 2009 In accordance with Section 221 of the Local Government Act 2001, attached is a Draft of the Annual Report and Accounts 2009. John Tierney Dublin City Manager DUBLIN CITY COUNCIL DRAFT ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2009 Contents: Lord Mayor’s Welcome To be included in Final Edition City Manager’s Welcome To be included in Final Edition Members of Dublin City Council 2009 To be included in Final Edition Senior Management Co-ordination Group To be included in Final Edition Sections: Driving Dublin’s Success Economic Development Social Cohesion Culture, Recreation and Amenity Urban Form Ease of Movement Environmental Sustainability Organisational Matters Appendices: 1. Members of Strategic Policy Committees at December 2009 2. Activities of Strategic Policy Committees 3. Members of Dublin City Development Board 2009 4. Dublin City Council National Services Indicators for 2009 5. Dublin City Council Development Contribution Scheme 6. Conferences and Seminars 2009 7. Recruitment Statistics 8. Publications published in 2009 9. Expenses and Payments 10. Dublin Joint Policing Committee Annual Financial Statements Introduction Statement of Accounting Policies 2009 Annual Financial Statements and General Driving Dublin’s Success Dublin in 2009 Dublin is Ireland’s capital city and is Ireland’s only globally competitive city. 2009 saw a number of dramatic changes at local, national and international levels. Dublin City Council must respond to the challenges presented and continue to serve the people of Dublin and deliver the major work programmes necessary for the smooth running and the future development of the city. -

20200214 Paul Loughlin Volume Two 2000 Hrs.Pdf

DEBATING CONTRACEPTION, ABORTION AND DIVORCE IN AN ERA OF CONTROVERSY AND CHANGE: NEW AGENDAS AND RTÉ RADIO AND TELEVISION PROGRAMMES 1968‐2018 VOLUME TWO: APPENDICES Paul Loughlin, M. Phil. (Dub) A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Professor Eunan O’Halpin Contents Appendix One: Methodology. Construction of Base Catalogue ........................................ 3 Catalogue ....................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. BASE PROGRAMME CATALOGUE CONSTRUCTION USING MEDIAWEB ...................................... 148 1.2. EXTRACT - MASTER LIST 3 LAST REVIEWED 22/11/2018. 17:15H ...................................... 149 1.3. EXAMPLES OF MEDIAWEB ENTRIES .................................................................................. 150 1.4. CONSTRUCTION OF A TIMELINE ........................................................................................ 155 1.5. RTÉ TRANSITION TO DIGITISATION ................................................................................... 157 1.6. DETAILS OF METHODOLOGY AS IN THE PREPARATION OF THIS THESIS PRE-DIGITISATION ............. 159 1.7. CITATION ..................................................................................................................... 159 Appendix Two: ‘Abortion Stories’ from the RTÉ DriveTime Series ................................ 166 2.1. ANNA’S STORY ............................................................................................................. -

An Roinn Comhshaoil

TOGHCHÁIN UACHTARÁIN 1938 – 2018 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS Prepared by the Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government housing.gov.ie 2 CONTENTS Page The Office of President 5 How the President is elected 7 Holders of the Office of President 13 Presidential Elections 1938 to 2018 19 Presidential Election 1938 20 Presidential Election 1945 20 Presidential Election 1952 24 Presidential Election 1959 24 Presidential Election 1966 26 Presidential Election 1973 28 Presidential Election 1974 30 Presidential Election 1976 30 Presidential Election 1983 30 Presidential Election 1990 31 Presidential Election 1997 34 Presidential Election 2004 37 Presidential Election 2011 39 Presidential Election 2018 49 3 4 The Office of President The office of President of Ireland (Uachtarán na hÉireann) was established by the Constitution in 1937. The President takes precedence over all other persons in the State and exercises powers and functions conferred by the Constitution and by law. The functions include: - appointment of the Taoiseach on the nomination of the Dáil; - appointment of the other members of the Government on the nomination of the Taoiseach with the previous approval of the Dáil; - acceptance of the resignation or termination of the appointment of a member of the Government on the advice of the Taoiseach; - summoning or dissolution of the Dáil on the advice of the Taoiseach (but the President may refuse to dissolve the Dáil on the advice of a Taoiseach who has ceased to retain the support of a majority in the Dáil); - signature of Bills passed by both Houses of the Oireachtas (but the President may, following consultation with the Council of State, refer a Bill to the Supreme Court for a ruling on its constitutionality. -

Reflections on 40 Years of Irish Membership of the EU

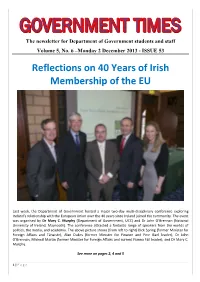

The newsletter for Department of Government students and staff Volume 5, No. 6 –Monday 2 December 2013 - ISSUE 53 Reflections on 40 Years of Irish Membership of the EU Last week, the Department of Government hosted a major two-day multi-disciplinary conference exploring Ireland’s relationship with the European Union over the 40 years since Ireland joined the community. The event was organised by Dr Mary C. Murphy (Department of Government, UCC) and Dr John O’Brennan (National University of Ireland, Maynooth). The conference attracted a fantastic range of speakers from the worlds of politics, the media, and academia. The above picture shows (from left to right) Dick Spring (former Minister for Foreign Affairs and Tánaiste), Alan Dukes (former Minister for Finance and Fine Gael leader), Dr John O’Brennan, Micheál Martin (former Minister for Foreign Affairs and current Fianna Fáil leader), and Dr Mary C. Murphy. See more on pages 2, 4 and 5 1 | P a g e Editorial Page Wishing everyone a happy, healthy and safe Christmas In some ways it’s hard to believe that the first semester is nearly at an end but what better way to celebrate than with a bumper 14-page issue of your favourite newsletter! Our lead story in Issue 53 is the highly successful EU conference held last week. The conference attracted a tremendous group of distinguished speakers and it was a great opportunity for Government students to hear first-hand accounts of Ireland’s relationship with the EU from leading politicians and academics as well as high-profile political correspondents. -

304 August 2010 Dublin

#304 August 2010 Dublin: UNESCO City of Literature Dublin City Public Libraries welcomes the wonderful news that the capital has been formally designated a UNESCO City of Literature, part of The Creative Cities Network. In receiving this accolade, Dublin proudly joins Edinburgh, Iowa City and Melbourne as one of only four cities in the world to bear the title of UNESCO City of Literature. City Librarian Margaret Hayes said ‘I am particularly pleased that Dublin City Council, through its library service, has played the lead role in winning this great honour – one which reflects the fact that although Dublin is indeed a literary city, it is the gateway to literary Ireland. It is my belief that Libraries all over the country can take real pride in this re-affirmation of our importance as cultural and literary ambassadors’. The sought after accolade was bestowed by the Director General of UNESCO and recognises Dublin’s cultural profile and its international standing as a city of literary excellence. Detailed application was made to UNESCO last November by a steering and management group led by Dublin City Council’s library service and was subject to a rigorous vetting procedure. Partners in the submission included representatives from literary-related organisations as well as culture, arts, tourism, government, media and educational institutions across the city and country. Visit the Dublin city of Literature website. Dublin’s writers explain why Dublin is a city of literature. For further information contact: Jane Alger 01 6744809. Bealtaine Festival, 2010 Bealtaine is a national festival celebrating creativity in older age and offers people over 55 the chance to try something new, to express their creative side or to come back to something they had not done for years. -

Decentralisation Deconstructed ++ a Study Decentralisation

TThhee IInnffoorrmmeerr COLLINS AND FINE GAEL TODAY WALK FOR PLUS Decentralisation deconstructed ++ A study of private education ++ Policy Manifesto Update The Official Ezine of Young Fine Gael September 2005 The Informer September 2005 Editorial So the summer passed away as quickly as it came, and Christmas is only 15 weeks away, so before we start the Christmas shopping, let me congratulate all those who passed their exams and are back for another year, commiserate with those who passed and are now finished and pass my deepest sympathies to those who have long since finished college. Let me also welcome any new members reading their first edition of the ‘YFG Informer’ especially the thousands of freshers enrolling in colleges around the country, may your year be successful as it is long, and may YFG be there to help you along the way. Welcome to the fourth edition of the ‘YFG Informer’. Inside, Michael Collins and what he means to Fine Gael, ‘The Intruder’ investigates President Pa O’ Driscoll. Decentralisation, Private Education, Blogging and reports from the President, Vice President and all around the country among others. But first let us reflect on the summer. Firstly to Summer school, which this year was hosted in the South East, namely, the Talbot Hotel, Wexford Town. Noted how the word ‘sunny’ was omitted. Well apart from the rain this was another tremendous success, hats off to Susie O’ Connor once again for this. Secondly, the Talk campaign continued to pick up momentum, as this was rolled out in major urban areas across the country and ‘memorably’ a sponsored walk from Galway to Limerick. -

PDF (Perspectives on Irish Homelessness)

Perspectives on Irish Homelessness: past, present and future Edited by Dáithí Downey Cover:Layout 1 30/06/2008 18:05 Page 1 Cover:Layout 1 30/06/2008 18:05 Page 2 © Homeless Agency and respective authors, 2008 The moral right of the Author to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with Copyright law. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise except as permitted by the Irish Copyright, Designs and Patents legislation, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published in 2008 by the Homeless Agency, Parkgate Hall, 6-9 Conyngham Road, Islandbridge, Dublin 8, Ireland. ISBN: 978-0-9559739-0-1 The views expressed by contributors to this publication are personal and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation they work for, or of the Homeless Agency, its Board of Management or its Consultative Forum. Inside:Layout 1 30/06/2008 16:42 Page 1 Perspectives on Irish Homelessness: Past, Present and Future Edited by Dáithí Downey Inside:Layout 1 30/06/2008 16:42 Page 2 CONTENTS Foreword.....................................................................................................................................................................................1 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................................................1 -

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION in IRELAND 27Th October 2011

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION IN IRELAND 27th October 2011 European Elections monitor A Record Number of Candidates in the Presidential Election in Ireland from Corinne Deloy Translated by Helen Levy 3.1 million Irish are being convened to vote for the second time this year. After having renewed the Chamber of Representatives (Dail Eireann), the Lower Chamber in Parliament, on 25th February ANALYSIS they will elect the successor to Mary Patricia McAleese to the presidency of the Republic on 27th 1 month before October next. Elected for the first time on 30th October 1997 with 45.2% of the vote (as Fianna the poll Fail’s candidate, she won ahead of the then Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Albert Reynolds in the race to be appointed as the party’s candidate)); she was then re-elected in October 2004. The only can- didate standing (on her own nomination, as stipulated in article 12.4.4 of the 1937 Constitution – Bunreacht na hEireann – for heads of State in office) for the supreme office when nominations were finalised, she was appointed without having to stand before the population. Born in Belfast, Mary Patricia McAleese was the first president of the Republic of Ireland to come from Northern Ireland, and is the third to have undertaken two consecutive terms in office, the last one dating back to, Ea- mon de Valera the father of the Irish nation, who was in office as Head of State from 1959 to 1973. The President of the Republic has done a great deal of the so-called alternative vote for a 7 year mandate that work to bring the communities living in the country to- can be renewed once. -

Broadcasting Authority of Ireland Public Consultation on the Draft

Broadcasting Authority of Ireland Public consultation on the Draft Code on fairness, impartiality and accountability in news and current affairs. Submission by 14th of March, 2012. Eóin Murray, NWCI, 4th floor, 4/5 Parnell square east, Dublin 1. E-mail: [email protected] Ph: 01-8898477 1. About the NWCI. 2. Introduction & background. 3. Portrayal and participation of women in the media. 4. Specific comments on the proposed BAI Code. 5. Conclusion. 6. Appendix one – research data from NWCI media-monitoring survey. 1. About the NWCI The National Women’s Council of Ireland (NWCI) is the representative body for women and women’s groups in Ireland, with 200 affiliated groups and organisations from the community, voluntary, professional and other key sectors of Irish society. The central purpose of the NWCI is to promote women's rights and women's equality. To achieve this end, our work falls under seven key areas: . Economic equality . Care . Political equality and decision making . Health and women’s human rights . Integration and anti-racism . Equality in public services . Building global and national solidarity In 2011 the AGM mandated the organisation to “address the issue of gender bias in Irish media, particularly in radio and TV panels and advertising.” Further to this a meeting of NWCI members was held in 2011 on the issue of women’s representation and participation in the media including expert panels and discussion groups. 2. Introduction & background The proposal for a draft code on fairness, impartiality and accountability in news and current affairs programming is most welcome and timely. The influence of broadcasters in the formation of opinion among significant segments of the population remains enormous. -

Activist Presidents and Gender Politics, 1990-2011

Transforming the Irish Presidency: Activist Presidents and Gender Politics, 1990-2011 Galligan, Y. (2012). Transforming the Irish Presidency: Activist Presidents and Gender Politics, 1990-2011. Irish Political Studies, 27(4), 596-614. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2012.734451 Published in: Irish Political Studies Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2012 Political Studies Association of Ireland. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article 20/11/2012, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/0.1080/07907184.2012.734451. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 7 / Transforming the Presidency: Activist Presidents and Gender Politics Yvonne Galligan Introduction The outcome of the 1990 and 1997 presidential elections brought two women into Áras an Uachtaráin, heralding a discernable change of pace, tone, and focus in the office. The relatively staid backwater that was the received image of the Irish presidency became charged with a new political energy.