City Report: Malmö, Sweden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participants

List of participants Conference of European Statisticians 69th Plenary Session, hybrid Wednesday, June 23 – Friday 25 June 2021 Registered participants Governments Albania Ms. Elsa DHULI Director General Institute of Statistics Ms. Vjollca SIMONI Head of International Cooperation and European Integration Sector Institute of Statistics Albania Argentina Sr. Joaquin MARCONI Advisor in International Relations, INDEC Mr. Nicolás PETRESKY International Relations Coordinator National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) Elena HASAPOV ARAGONÉS National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) Armenia Mr. Stepan MNATSAKANYAN President Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia Ms. Anahit SAFYAN Member of the State Council on Statistics Statistical Committee of RA Australia Mr. David GRUEN Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics 1 Ms. Teresa DICKINSON Deputy Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics Ms. Helen WILSON Deputy Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics Austria Mr. Tobias THOMAS Director General Statistics Austria Ms. Brigitte GRANDITS Head International Relation Statistics Austria Azerbaijan Mr. Farhad ALIYEV Deputy Head of Department State Statistical Committee Mr. Yusif YUSIFOV Deputy Chairman The State Statistical Committee Belarus Ms. Inna MEDVEDEVA Chairperson National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Ms. Irina MAZAISKAYA Head of International Cooperation and Statistical Information Dissemination Department National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Ms. Elena KUKHAREVICH First Deputy Chairperson National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Belgium Mr. Roeland BEERTEN Flanders Statistics Authority Mr. Olivier GODDEERIS Head of international Strategy and coordination Statistics Belgium 2 Bosnia and Herzegovina Ms. Vesna ĆUŽIĆ Director Agency for Statistics Brazil Mr. Eduardo RIOS NETO President Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE Sra. -

Statistical Confidentiality and Access to Microdata

UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE STATISTICAL CONFIDENTIALITY AND ACCESS TO MICRODATA Proceedings of the Seminar Session of the 2003 Conference of European Statisticians UNITED NATIONS UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE STATISTICAL CONFIDENTIALITY AND ACCESS TO MICRODATA Proceedings of the Seminar Session of the 2003 Conference of European Statisticians UNITED NATIONS NEW YORK AND GENEVA 2003 Note The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations. FOREWORD At the 51st plenary session of the Conference of European Statisticians (CES) held in Geneva, 10-12 June 2003, one of the two seminars was devoted to the issue of statistical confidentiality and access to microdata. This seminar was organized and chaired by Statistics Sweden in cooperation with the CES Bureau. Since the seminar was regarded as very fruitful, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) and Statistics Sweden decided to make a joint publication of the proceedings of the seminar. The Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics, adopted by the Economic Commission for Europe in 1992, include a principle, according to which “Official statistics provide an indispensable element in the information system of a democratic society…”. Furthermore “…individual data collected by statistical agencies for statistical compilation, whether they refer to natural or legal persons, are to be strictly confidential and used exclusively for statistical purposes”. When discussing microdata, the main challenge for statistical offices is to ensure that the improved access to microdata will not undermine the confidentiality principle, both in reality and in the perception of the public and respondents to statistical surveys. -

Celebrating the Establishment, Development and Evolution of Statistical Offices Worldwide: a Tribute to John Koren

Statistical Journal of the IAOS 33 (2017) 337–372 337 DOI 10.3233/SJI-161028 IOS Press Celebrating the establishment, development and evolution of statistical offices worldwide: A tribute to John Koren Catherine Michalopouloua,∗ and Angelos Mimisb aDepartment of Social Policy, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Athens, Greece bDepartment of Economic and Regional Development, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Athens, Greece Abstract. This paper describes the establishment, development and evolution of national statistical offices worldwide. It is written to commemorate John Koren and other writers who more than a century ago published national statistical histories. We distinguish four broad periods: the establishment of the first statistical offices (1800–1914); the development after World War I and including World War II (1918–1944); the development after World War II including the extraordinary work of the United Nations Statistical Commission (1945–1974); and, finally, the development since 1975. Also, we report on what has been called a “dark side of numbers”, i.e. “how data and data systems have been used to assist in planning and carrying out a wide range of serious human rights abuses throughout the world”. Keywords: National Statistical Offices, United Nations Statistical Commission, United Nations Statistics Division, organizational structure, human rights 1. Introduction limitations to this power. The limitations in question are not constitutional ones, but constraints that now Westergaard [57] labeled the period from 1830 to seemed to exist independently of any formal arrange- 1849 as the “era of enthusiasm” in statistics to indi- ments of government.... The ‘era of enthusiasm’ in cate the increasing scale of their collection. -

Skane Facts-And-Key-Trends.Pdf

SKÅNE – FACTS AND KEY TRENDS Utgivningsår: 2017 Rapporten är framtagen av Region Skåne och Helsingborgs Stad 2017 inom ramen för OECD studien OECD Territorial Review Megaregion Western Scandinavia Författare: Madeleine Nilsson, Christian Lindell, David Sandin, Daniel Svärd, Henrik Persson, Johanna Edlund och många fler. Projektledare: Madeleine Nilsson, [email protected], Region Skåne. Projektledare för Skånes del i OECD TR Megaregion Western Scandinavia 1 Foreword Region Skåne and the City of Helsingborg, together with partners in Western Sweden and the Oslo region, have commissioned the OECD to conduct a so-called Territorial Review of the Megaregion Western Scandinavia. A review of opportunities and potential for greater integration and cooperation between the regions and cities in Western Scandinavia. This report is a brief summary of the supporting data submitted by Skåne to the OECD in December 2016 and mainly contains regional trends, strengths and weaknesses. The report largely follows the arrangement of all the supporting data submitted to the OECD, however, the policy sections have been omitted. All the data sets have been produced by a number of employees of Region Skåne and the City of Helsingborg. During the spring, corresponding reports have been produced for both Western Sweden and the Oslo region. The first study mission was conducted by the OECD in January 2017, where they met with experts and representatives from Skåne and the Megaregion. In late April, the OECD will be visiting Skåne and the Megaregion again with peer reviewers from Barcelona, Vienna and Vancouver for a second round of study mission. The OECD’s final report will be presented and decided upon within the OECD Regional Development Policy Committee (RDPC) in December 2017, and subsequently the OECD Territorial Review Megaregion Western Scandinavia will be published. -

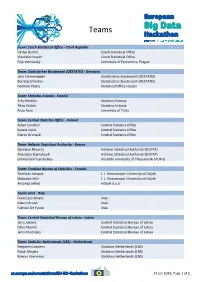

European Big Data Hackathon

Teams Team: Czech Statistical Office - Czech Republic Václav Bartoš Czech Statistical Office Vlastislav Novák Czech Statistical Office Filip Vencovský University of Economics, Prague Team: Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) - Germany Jana Emmenegger Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) Bernhard Fischer Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) Normen Peters Statistical Office Hessen Team: Statistics Estonia - Estonia Arko Kesküla Statistics Estonia Tõnu Raitviir Statistics Estonia Anto Aasa University of Tartu Team: Central Statistics Office - Ireland Aidan Condron Central Statistics Office Sanela Jojkic Central Statistics Office Marco Grimaldi Central Statistics Office Team: Hellenic Statistical Authority - Greece Georgios Ntouros Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) Anastasia Stamatoudi Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) Emmanouil Tsardoulias Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTH) Team: Croatian Bureau of Statistics - Croatia Tomislav Jakopec J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Slobodan Jelić J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Antonija Jelinić mStart d.o.o Team: Istat - Italy Francesco Amato Istat Mauro Bruno Istat Fabrizio De Fausti Istat Team: Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia - Latvia Janis Jukams Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia Dāvis Kļaviņš Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia Jānis Muižnieks Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia Team: Statistics Netherlands (CBS) - Netherlands Benjamin Laevens Statistics Netherlands (CBS) Ralph Meijers Statistics Netherlands (CBS) Rowan Voermans Statistics Netherlands (CBS) 31 -

Annex 3: Sources, Methods and Technical Notes

Annex 3 EAG 2007 Education at a Glance OECD Indicators 2007 Annex 3: Sources 1 Annex 3 EAG 2007 SOURCES IN UOE DATA COLLECTION 2006 UNESCO/OECD/EUROSTAT (UOE) data collection on education statistics. National sources are: Australia: - Department of Education, Science and Training, Higher Education Group, Canberra; - Australian Bureau of Statistics (data on Finance; data on class size from a survey on Public and Private institutions from all states and territories). Austria: - Statistics Austria, Vienna; - Federal Ministry for Education, Science and Culture, Vienna (data on Graduates); (As from 03/2007: Federal Ministry for Education, the Arts and Culture; Federal Ministry for Science and Research) - The Austrian Federal Economic Chamber, Vienna (data on Graduates). Belgium: - Flemish Community: Flemish Ministry of Education and Training, Brussels; - French Community: Ministry of the French Community, Education, Research and Training Department, Brussels; - German-speaking Community: Ministry of the German-speaking Community, Eupen. Brazil: - Ministry of Education (MEC) - Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) Canada: - Statistics Canada, Ottawa. Chile: - Ministry of Education, Santiago. Czech Republic: - Institute for Information on Education, Prague; - Czech Statistical Office Denmark: - Ministry of Education, Budget Division, Copenhagen; - Statistics Denmark, Copenhagen. 2 Annex 3 EAG 2007 Estonia - Statistics office, Tallinn. Finland: - Statistics Finland, Helsinki; - National Board of Education, Helsinki (data on Finance). France: - Ministry of National Education, Higher Education and Research, Directorate of Evaluation and Planning, Paris. Germany: - Federal Statistical Office, Wiesbaden. Greece: - Ministry of National Education and Religious Affairs, Directorate of Investment Planning and Operational Research, Athens. Hungary: - Ministry of Education, Budapest; - Ministry of Finance, Budapest (data on Finance); Iceland: - Statistics Iceland, Reykjavik. -

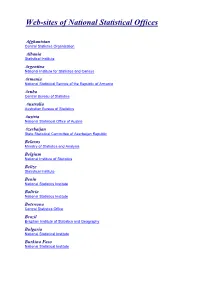

Web-Sites of National Statistical Offices

Web-sites of National Statistical Offices Afghanistan Central Statistics Organization Albania Statistical Institute Argentina National Institute for Statistics and Census Armenia National Statistical Service of the Republic of Armenia Aruba Central Bureau of Statistics Australia Australian Bureau of Statistics Austria National Statistical Office of Austria Azerbaijan State Statistical Committee of Azerbaijan Republic Belarus Ministry of Statistics and Analysis Belgium National Institute of Statistics Belize Statistical Institute Benin National Statistics Institute Bolivia National Statistics Institute Botswana Central Statistics Office Brazil Brazilian Institute of Statistics and Geography Bulgaria National Statistical Institute Burkina Faso National Statistical Institute Cambodia National Institute of Statistics Cameroon National Institute of Statistics Canada Statistics Canada Cape Verde National Statistical Office Central African Republic General Directorate of Statistics and Economic and Social Studies Chile National Statistical Institute of Chile China National Bureau of Statistics Colombia National Administrative Department for Statistics Cook Islands Statistics Office Costa Rica National Statistical Institute Côte d'Ivoire National Statistical Institute Croatia Croatian Bureau of Statistics Cuba National statistical institute Cyprus Statistical Service of Cyprus Czech Republic Czech Statistical Office Denmark Statistics Denmark Dominican Republic National Statistical Office Ecuador National Institute for Statistics and Census Egypt -

Sources and Data Description

OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2018 © OECD 2018 ANNEX B Sources and data description User guide: List of variables Variables used Page Chapter(s) Area 144 2 Business demography, births and deaths of enterprises 144 1 Employment at place of work and gross value added by industry 145 1 Foreign-born (migrants) 145 4 Gross domestic product (GDP) 146 1 Homicides 147 2 Household disposable income 148 2, 4 Households with broadband connection 149 2 Housing expenditures as a share of household disposable income 150 2 Income segregation in cities 151 4 Labour force, employment at place of residence by gender, unemployment 152 2 Labour force by educational attainment 152 2 Life expectancy at birth, total and by gender 153 2 Metropolitan population 154 4 Motor vehicle theft 155 2 Patents applications 155 1 PM2.5 particle concentration 155 2, 4 Population mobility among regions 156 3 Population, total, by age and gender 157 3 R&D expenditure and R&D personnel 158 1 Rooms per person (number of) 159 2 Subnational government expenditure, revenue, investment and debt 160 5 Voter turnout 160 2 Note on Israel: The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. 143 ANNEX B Area Country Source EU24 countries1 Eurostat: General and regional statistics, demographic statistics, population and area Australia Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), summing up SLAs Canada Statistics Canada http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census01/products/standard/popdwell/Table-CD-P. -

Sources and Data Description

ANNEX B ANNEX B Sources and data description User guide: List of variables Variables used Page Chapter(s) Area 147 2 Age-adjusted mortality rates based on mortality data 148 1 Death rates due to diseases of the respiratory system 148 1 Employment at place of work and gross value added by industry 149 2 Gini index of household disposable income 149 1 Gross domestic product (GDP) 150 2 Homicides 151 1 Hospital beds 152 4 Household disposable income 153 1 Households with broadband connection 154 4 Housing expenditures as a share of household disposable income 155 1 Individuals with unmet medical needs 155 1 Labour force, employment at place of residence by gender, unemployment, total and growth 156 1 and 2 Labour force by educational attainment 158 1 Life expectancy at birth, total and by gender 159 1 Life satisfaction 159 1 Local governments in metropolitan areas 160 2 Metropolitan population, total and by age 161 2 Motor vehicle theft 162 1 Municipal waste and recycled waste 163 4 Number of rooms per person 163 1 Part-time employment 164 4 Perception of corruption 164 1 PCT patent and co-patent applications, total and by sector 165 2 Physicians 165 4 PM2.5 particle concentration 166 1 Population, total, by age and gender 166 2 Population mobility among regions 167 4 R&D expenditure 169 2 R&D personnel 170 2 Social network support 170 1 Subnational government expenditure, revenue, investment and debt 171 3 Voter turnout 171 1 Young population neither in employment nor in education or training 172 4 Youth unemployment 173 4 The tables refer to the years and territorial levels used in this publication. -

European Big Data Hackathon

Teams Team: National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria - Bulgaria Sergi Sergiev National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria Valentin Chavdarov National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria Vladimir Kanchev National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria Team: Statistics Denmark - Denmark Maria Holm Statistics Denmark Niels Jespersen Statistics Denmark Olav Grøndal Statistics Denmark Team: Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) - Germany Lara Adrienne Wiengarten Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) Malte Schierholz Institute for Employment Research (IAB) Simon Rothmeier Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) Team: Statistics Estonia - Estonia Innar Liiv Tallinn University of Technology Rain Öpik DeltaBid Toomas Kirt Statistics Estonia Team: Central Statistics Office - Ireland Bruno Voisin Irish Centre for High-End Computing Eoin O'Connell Department of Justice Paul Rockley Central Statistics Office Team: Hellenic Statistical Authority - Greece Michail Mylonakis Hellenic Statistical Authority Nikolaos Bompetsis Hellenic Statistical Authority Panagiotis Vlantis Hellenic Statistical Authority Team: National Statistical Institute (INE) - Spain Jose Antonio da Rocha Padilla National Statistical Institute (INE) Luis Sanguiao Sande National Statistical Institute (INE) Miguel V. Espada University Complutense of Madrid Team: INSEE - France Benjamin Sakarovitch INSEE Stéphanie Combes INSEE Yves-Laurent Benichou INSEE 15 Feb 2017, Page 1 of 3 Team: Croatian Bureau of Statistics - Croatia Igor Kaluđer IN2data / Algebra University College Zagreb Leo Mrsic IN2data / Algebra -

10. References

10. References Previous 9. Glossary of terms and abbreviations Up Contents ABS, Strategy for End-to-End Management of ABS Metadata, (2003) AMRADS, EU project, Final Report of the Working Group on Metadata, (2003) Booleman, M, Statistics Netherlands, The Dutch Metadata Model, (2004) Cluster of Systems of Metadata for Official Statistics (COSMOS), http://www.epros.ed.ac.uk/cosmos/ Czech Statistical Office, Conception of the Statistical Metadata System in the Czech Statistical Office, (2004) Czech Statistical Office, Global Architecture of the Statistical Meta-information System in the Czech Statistical Office, (2005) Eurostat, Eurostat Metadata: Architecture and Strategy, (2003) SDMX, Metadata Common Vocabulary, (2009), http://www.sdmx.org SDMX, Content-Oriented Guidelines, (2009), http://www.sdmx.org Hustoft, A, Statistics Norway, Development of a Variables Documentation System in Statistics Norway, (2004) http://www.ssb.no/english/subjects/00 /doc_200713_en/doc_200713_en.pdf Lindblom, H, Statistics Sweden, The Metadata System at Statistics Sweden in an International Perspective, (2004) Meliskova, J, AMRADS project, External Users of Metadata: a Challenge for National Statistical Offices, (2003) OECD, Data and Metadata Reporting and Presentation Handbook, (2007), http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/46/17/37671574.pdf OECD, Management of Statistical Metadata at the OECD, (2006), http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/26/33/33869551.pdf Sundgren, B, Statistics Sweden, Advice Concerning the Strategic Decisions that have to be made by a Statistical Office when -

Sweden Facing Climate Change – Threats and Opportunities

Sweden facing climate change – threats and opportunities Final report from the Swedish Commission on Climate and Vulnerability Stockholm 2007 Swedish Government Official Reports SOU 2007:60 This report is on sale in Stockholm at Fritzes Bookshop. Address: Fritzes, Customer Service, SE-106 47 STOCKHOLM Sweden Fax: 08 690 91 91 (national) +46 8 690 91 91 (international) Tel: 08 690 91 90 (national) +46 8 690 91 91 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.fritzes.se Printed by Edita Sverige AB Stockholm 2007 ISBN 978-91-38-22850-0 ISSN 0375-250X Preface The Commission on Climate and Vulnerability was appointed by the Swedish Government in June 2005 to assess regional and local impacts of global climate change on the Swedish society including costs. Bengt Holgersson Governor of the County Administrative Board in the region of Skåne was appointed head of the Com- mission. This report will be subject to a public review and will serve as one of the inputs to a forthcoming climate bill in 2008. The author have the sole responsibility for the content of the report and as such it can not be taken as the view of the Swedish Government. This report was originally produced in Swedish. It has been translated into English and the English version corresponds with the Swedish one. However, one chapter with specific proposals for changes in Swedish legislation was not translated, nor were the appendices translated. Hence, these are only available in the Swedish original version. Contents 1 Summary................................................................... 11 2 The assignment and background.................................. 35 2.1 The assignment, scope and approach.....................................