Immigrants in Norway, Sweden and Denmark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participants

List of participants Conference of European Statisticians 69th Plenary Session, hybrid Wednesday, June 23 – Friday 25 June 2021 Registered participants Governments Albania Ms. Elsa DHULI Director General Institute of Statistics Ms. Vjollca SIMONI Head of International Cooperation and European Integration Sector Institute of Statistics Albania Argentina Sr. Joaquin MARCONI Advisor in International Relations, INDEC Mr. Nicolás PETRESKY International Relations Coordinator National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) Elena HASAPOV ARAGONÉS National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) Armenia Mr. Stepan MNATSAKANYAN President Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia Ms. Anahit SAFYAN Member of the State Council on Statistics Statistical Committee of RA Australia Mr. David GRUEN Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics 1 Ms. Teresa DICKINSON Deputy Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics Ms. Helen WILSON Deputy Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics Austria Mr. Tobias THOMAS Director General Statistics Austria Ms. Brigitte GRANDITS Head International Relation Statistics Austria Azerbaijan Mr. Farhad ALIYEV Deputy Head of Department State Statistical Committee Mr. Yusif YUSIFOV Deputy Chairman The State Statistical Committee Belarus Ms. Inna MEDVEDEVA Chairperson National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Ms. Irina MAZAISKAYA Head of International Cooperation and Statistical Information Dissemination Department National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Ms. Elena KUKHAREVICH First Deputy Chairperson National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Belgium Mr. Roeland BEERTEN Flanders Statistics Authority Mr. Olivier GODDEERIS Head of international Strategy and coordination Statistics Belgium 2 Bosnia and Herzegovina Ms. Vesna ĆUŽIĆ Director Agency for Statistics Brazil Mr. Eduardo RIOS NETO President Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE Sra. -

Oecd Short-Term Economic Statistics Working Party (Steswp)

OECD SHORT-TERM ECONOMIC STATISTICS WORKING PARTY (STESWP) Future evolution of short-term economic economic statistics collected and disseminated by the OECD and national agencies: summary of national comments Paper prepared by Denis Ward Statistics Directorate, OECD Submitted to the Working Party under item 10 of the draft agenda Meeting: 26 – 28 June 2006 Franqueville Room OECD Headquarters, Paris Starting at 9:30 a.m. on the first day FUTURE EVOLUTION OF SHORT-TERM ECONOMIC STATISTICS COLLECTED AND DISSEMINATED BY THE OECD AND NATIONAL AGENCIES SUMMARY OF NATIONAL COMMENTS AUSTRIA (Statistics Austria) The further evolution of STS in Austria depends on the evolution of legal request by the European Union. Priorities are the work for the revision of NACE and the change of the base year (2005=100) as they involve comprehensive conceptual changes in short-term economic statistics. Austria is concentrating on the implementation of and the compliance with the requests of the amended STS-Regulation and on the satisfaction of national user’s needs, that is: • improvements in timeliness: release of the IPI at t+55 respectively t+30 or t+40 from base 2005=100 for determined aggregates • compilation of eurozone/non-eurozone indicators, • conduct of feasibility studies concerning the variables hours worked and wages and salaries in services and conceptual work in the area of trade and services • transition to NACE Rev.2 (including methods for backcasting, new sample etc.) • new web dissemination policy • satisfaction of national needs on regional level (NUTS 2): compilation of production index on NUTS 2 level; it is planned to compile turnover and labour input indicators for NACE section H, hotels and restaurants • more advanced use of administrative data Resources for new variables (e.g. -

Statistical Confidentiality and Access to Microdata

UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE STATISTICAL CONFIDENTIALITY AND ACCESS TO MICRODATA Proceedings of the Seminar Session of the 2003 Conference of European Statisticians UNITED NATIONS UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE STATISTICAL CONFIDENTIALITY AND ACCESS TO MICRODATA Proceedings of the Seminar Session of the 2003 Conference of European Statisticians UNITED NATIONS NEW YORK AND GENEVA 2003 Note The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations. FOREWORD At the 51st plenary session of the Conference of European Statisticians (CES) held in Geneva, 10-12 June 2003, one of the two seminars was devoted to the issue of statistical confidentiality and access to microdata. This seminar was organized and chaired by Statistics Sweden in cooperation with the CES Bureau. Since the seminar was regarded as very fruitful, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) and Statistics Sweden decided to make a joint publication of the proceedings of the seminar. The Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics, adopted by the Economic Commission for Europe in 1992, include a principle, according to which “Official statistics provide an indispensable element in the information system of a democratic society…”. Furthermore “…individual data collected by statistical agencies for statistical compilation, whether they refer to natural or legal persons, are to be strictly confidential and used exclusively for statistical purposes”. When discussing microdata, the main challenge for statistical offices is to ensure that the improved access to microdata will not undermine the confidentiality principle, both in reality and in the perception of the public and respondents to statistical surveys. -

Channels of Entry and Preferred Destinations: the Circumvention of Denmark by Chinese Immigrants

Channels of Entry and Preferred Destinations: The Circumvention of Denmark by Chinese Immigrants Mette Thunø* ABSTRACT As globalization spread during the 1990s, and especially since the turn of the millennium, European states have increasingly claimed their right to assert their sovereignty by regulating migration at the level of the individual (OECD, 2001: 76-81). Political parties have succeeded in gaining support on policy statements pertaining exclusively to migration. For example, recent legislation in Denmark restricts the categories of persons eligible as refugees to “Convention refugees” satisfying only the narrowest international criteria set out in the UN Refugee Convention. The civil rights of asylum seekers are restricted by prohibiting mar- riage while their applications are under review. To limit family reunification among immigrants, the present Danish Government has even prohibited immi- grants with permanent residence status and Danish citizens from bringing non- Danish spouses under age 24 into the country. These attempts at border enforcement and immigration control have been de- scribed by some critics as the endeavours of European Union (EU) members to build a “Fortress Europe” against immigrants from developing countries. Policy decisions and the implementation of various measures from finger printing to radar surveillance to control immigrants have corroborated such perceptions, but this paper will show that gaining entry to a highly controlled country such as Denmark from a poorer country such as the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is fairly straightforward. Politicians may wish to convey the impression of being in control of international mobility by launching diverse anti-immigration acts, but since the immigration embargo of the early 1970s all EU countries have received millions of immigrants, and increasingly permit or accept immigrants of various kinds to reside and work within their borders (Boeri et al., 2002). -

Celebrating the Establishment, Development and Evolution of Statistical Offices Worldwide: a Tribute to John Koren

Statistical Journal of the IAOS 33 (2017) 337–372 337 DOI 10.3233/SJI-161028 IOS Press Celebrating the establishment, development and evolution of statistical offices worldwide: A tribute to John Koren Catherine Michalopouloua,∗ and Angelos Mimisb aDepartment of Social Policy, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Athens, Greece bDepartment of Economic and Regional Development, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Athens, Greece Abstract. This paper describes the establishment, development and evolution of national statistical offices worldwide. It is written to commemorate John Koren and other writers who more than a century ago published national statistical histories. We distinguish four broad periods: the establishment of the first statistical offices (1800–1914); the development after World War I and including World War II (1918–1944); the development after World War II including the extraordinary work of the United Nations Statistical Commission (1945–1974); and, finally, the development since 1975. Also, we report on what has been called a “dark side of numbers”, i.e. “how data and data systems have been used to assist in planning and carrying out a wide range of serious human rights abuses throughout the world”. Keywords: National Statistical Offices, United Nations Statistical Commission, United Nations Statistics Division, organizational structure, human rights 1. Introduction limitations to this power. The limitations in question are not constitutional ones, but constraints that now Westergaard [57] labeled the period from 1830 to seemed to exist independently of any formal arrange- 1849 as the “era of enthusiasm” in statistics to indi- ments of government.... The ‘era of enthusiasm’ in cate the increasing scale of their collection. -

Skane Facts-And-Key-Trends.Pdf

SKÅNE – FACTS AND KEY TRENDS Utgivningsår: 2017 Rapporten är framtagen av Region Skåne och Helsingborgs Stad 2017 inom ramen för OECD studien OECD Territorial Review Megaregion Western Scandinavia Författare: Madeleine Nilsson, Christian Lindell, David Sandin, Daniel Svärd, Henrik Persson, Johanna Edlund och många fler. Projektledare: Madeleine Nilsson, [email protected], Region Skåne. Projektledare för Skånes del i OECD TR Megaregion Western Scandinavia 1 Foreword Region Skåne and the City of Helsingborg, together with partners in Western Sweden and the Oslo region, have commissioned the OECD to conduct a so-called Territorial Review of the Megaregion Western Scandinavia. A review of opportunities and potential for greater integration and cooperation between the regions and cities in Western Scandinavia. This report is a brief summary of the supporting data submitted by Skåne to the OECD in December 2016 and mainly contains regional trends, strengths and weaknesses. The report largely follows the arrangement of all the supporting data submitted to the OECD, however, the policy sections have been omitted. All the data sets have been produced by a number of employees of Region Skåne and the City of Helsingborg. During the spring, corresponding reports have been produced for both Western Sweden and the Oslo region. The first study mission was conducted by the OECD in January 2017, where they met with experts and representatives from Skåne and the Megaregion. In late April, the OECD will be visiting Skåne and the Megaregion again with peer reviewers from Barcelona, Vienna and Vancouver for a second round of study mission. The OECD’s final report will be presented and decided upon within the OECD Regional Development Policy Committee (RDPC) in December 2017, and subsequently the OECD Territorial Review Megaregion Western Scandinavia will be published. -

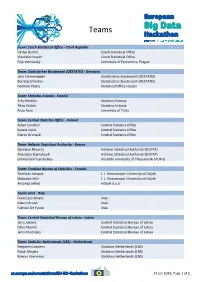

European Big Data Hackathon

Teams Team: Czech Statistical Office - Czech Republic Václav Bartoš Czech Statistical Office Vlastislav Novák Czech Statistical Office Filip Vencovský University of Economics, Prague Team: Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) - Germany Jana Emmenegger Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) Bernhard Fischer Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) Normen Peters Statistical Office Hessen Team: Statistics Estonia - Estonia Arko Kesküla Statistics Estonia Tõnu Raitviir Statistics Estonia Anto Aasa University of Tartu Team: Central Statistics Office - Ireland Aidan Condron Central Statistics Office Sanela Jojkic Central Statistics Office Marco Grimaldi Central Statistics Office Team: Hellenic Statistical Authority - Greece Georgios Ntouros Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) Anastasia Stamatoudi Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) Emmanouil Tsardoulias Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTH) Team: Croatian Bureau of Statistics - Croatia Tomislav Jakopec J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Slobodan Jelić J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Antonija Jelinić mStart d.o.o Team: Istat - Italy Francesco Amato Istat Mauro Bruno Istat Fabrizio De Fausti Istat Team: Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia - Latvia Janis Jukams Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia Dāvis Kļaviņš Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia Jānis Muižnieks Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia Team: Statistics Netherlands (CBS) - Netherlands Benjamin Laevens Statistics Netherlands (CBS) Ralph Meijers Statistics Netherlands (CBS) Rowan Voermans Statistics Netherlands (CBS) 31 -

Annex 3: Sources, Methods and Technical Notes

Annex 3 EAG 2007 Education at a Glance OECD Indicators 2007 Annex 3: Sources 1 Annex 3 EAG 2007 SOURCES IN UOE DATA COLLECTION 2006 UNESCO/OECD/EUROSTAT (UOE) data collection on education statistics. National sources are: Australia: - Department of Education, Science and Training, Higher Education Group, Canberra; - Australian Bureau of Statistics (data on Finance; data on class size from a survey on Public and Private institutions from all states and territories). Austria: - Statistics Austria, Vienna; - Federal Ministry for Education, Science and Culture, Vienna (data on Graduates); (As from 03/2007: Federal Ministry for Education, the Arts and Culture; Federal Ministry for Science and Research) - The Austrian Federal Economic Chamber, Vienna (data on Graduates). Belgium: - Flemish Community: Flemish Ministry of Education and Training, Brussels; - French Community: Ministry of the French Community, Education, Research and Training Department, Brussels; - German-speaking Community: Ministry of the German-speaking Community, Eupen. Brazil: - Ministry of Education (MEC) - Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) Canada: - Statistics Canada, Ottawa. Chile: - Ministry of Education, Santiago. Czech Republic: - Institute for Information on Education, Prague; - Czech Statistical Office Denmark: - Ministry of Education, Budget Division, Copenhagen; - Statistics Denmark, Copenhagen. 2 Annex 3 EAG 2007 Estonia - Statistics office, Tallinn. Finland: - Statistics Finland, Helsinki; - National Board of Education, Helsinki (data on Finance). France: - Ministry of National Education, Higher Education and Research, Directorate of Evaluation and Planning, Paris. Germany: - Federal Statistical Office, Wiesbaden. Greece: - Ministry of National Education and Religious Affairs, Directorate of Investment Planning and Operational Research, Athens. Hungary: - Ministry of Education, Budapest; - Ministry of Finance, Budapest (data on Finance); Iceland: - Statistics Iceland, Reykjavik. -

Rural Infant Mortality in Nineteenth Century Norway1

Rural Infant Mortality in Nineteenth Century Norway1 Gunnar Thorvaldsen uch previous research on the Norwegian mortality decline has focused on specific localities, employing databases with linked microdata. One Mgood choice is Rendalen, a parish on the Swedish border, representative of the world record low Norwegian mortality rates. The focus on the role of women, given their access to more abundant material resources towards the end of the eighteenth century, is a most interesting explanation for the declining level of infant mortality.2 Another well-researched locality is the fjord-parish Etne, south of Bergen, where infant mortality was significantly higher – also an area where the role of women is highlighted. More recent studies have been done on Asker and Bærum, south of Oslo, with infant mortality levels closer to the national average. The present article will not attempt to match these penetrating studies of well- researched rural localities, nor William Hubbard’s insights into many aspects of urban mortality.3 Rather it broadens the scope to include the whole country. My study is limited primarily to Norway’s sparsely populated rural areas, where 90 percent of the population lived in 1801, a figure that was declining towards 60 percent by 1900, when the national infant mortality rate (IMR) had fallen below ten percent.4 My basic aim is to track the development of infant mortality rates in Norway over time, and, where possible, to say something about regional differences in the proportion of children who died before they reached their first birthday. The 1 Another version of this article will also be published inStudies in Mortality Decline. -

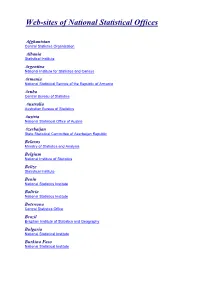

Web-Sites of National Statistical Offices

Web-sites of National Statistical Offices Afghanistan Central Statistics Organization Albania Statistical Institute Argentina National Institute for Statistics and Census Armenia National Statistical Service of the Republic of Armenia Aruba Central Bureau of Statistics Australia Australian Bureau of Statistics Austria National Statistical Office of Austria Azerbaijan State Statistical Committee of Azerbaijan Republic Belarus Ministry of Statistics and Analysis Belgium National Institute of Statistics Belize Statistical Institute Benin National Statistics Institute Bolivia National Statistics Institute Botswana Central Statistics Office Brazil Brazilian Institute of Statistics and Geography Bulgaria National Statistical Institute Burkina Faso National Statistical Institute Cambodia National Institute of Statistics Cameroon National Institute of Statistics Canada Statistics Canada Cape Verde National Statistical Office Central African Republic General Directorate of Statistics and Economic and Social Studies Chile National Statistical Institute of Chile China National Bureau of Statistics Colombia National Administrative Department for Statistics Cook Islands Statistics Office Costa Rica National Statistical Institute Côte d'Ivoire National Statistical Institute Croatia Croatian Bureau of Statistics Cuba National statistical institute Cyprus Statistical Service of Cyprus Czech Republic Czech Statistical Office Denmark Statistics Denmark Dominican Republic National Statistical Office Ecuador National Institute for Statistics and Census Egypt -

Deltagerliste Sorteret I Landeorden 020517.Xlsx

COUNTRY FIRSTNAME LASTNAME EMAIL ORGANISATION Albania Pranvera Elezi [email protected] Institute of Statistics, INSTAT Austria Katrin Baumgartner [email protected] Statistics Austria Austria Judith Forster [email protected] Statistics Austria Belgium Filip Tanay [email protected] European Commission Bosnia and Herzegovina Svjetlana Kezunovic [email protected] Agency for statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina Kostova- Bulgaria Tsveta Sevastiyanova [email protected] National statistical institute Cyprus Eleni Christodoulidou [email protected] Statistical Service of Cyprus Denmark Sofie Valentin [email protected] Statistics Denmark Denmark Sven Egmose [email protected] Statistics Denmark Denmark Lisbeth Johansen [email protected] Statistics Denmark Denmark Wendy Takacs Jensen [email protected] Statistics Denmark Denmark Tine Cordes [email protected] Statistics Denmark Denmark Martin Nielsen [email protected] Statistics Denmark Denmark Lars Peter Christensen [email protected] DST Estonia Ülle Pettai [email protected] Statistics Estonia Finland Anna Pärnänen [email protected] Statistics Finland Finland Hanna Sutela [email protected] Statistics Finland France Simon Beck [email protected] Insee France Jonathan Brendler [email protected] INSEE Germany Lisa Guenther [email protected] Federal Statistical Office Hungary Krisztina Mezey [email protected] Hungarian Central Statistical Office Iceland Ólafur Már Sigurðsson [email protected] Statistics Iceland Ireland Edel Flannery [email protected] Central -

OECD SOCIAL, EMPLOYMENT and MIGRATION WORKING PAPERS the Labour Market Integration of Immigrants in Denmark Thomas Liebig

DELSA/ELSA/WD/SEM(2007)5 The Labour Market Integration of Immigrants in Denmark Thomas Liebig 50 OECD SOCIAL, EMPLOYMENT AND MIGRATION WORKING PAPERS Unclassified DELSA/ELSA/WD/SEM(2007)5 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 05-Mar-2007 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English - Or. English DIRECTORATE FOR EMPLOYMENT, LABOUR AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS EMPLOYMENT, LABOUR AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS COMMITTEE Unclassified DELSA/ELSA/WD/SEM(2007)5 OECD SOCIAL, EMPLOYMENT AND MIGRATION WORKING PAPERS No.50 THE LABOUR MARKET INTEGRATION OF IMMIGRANTS IN DENMARK Thomas Liebig J15, J21, J61, J62, J68, J7, J8 English - Or. English JT03222979 Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format DELSA/ELSA/WD/SEM(2007)5 DIRECTORATE FOR EMPLOYMENT, LABOUR AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS http://www.oecd.org/els OECD SOCIAL, EMPLOYMENT AND MIGRATION WORKING PAPERS http://www.oecd.org/els/workingpapers This series is designed to make available to a wider readership selected labour market, social policy and migration studies prepared for use within the OECD. Authorship is usually collective, but principal writers are named. The papers are generally available only in their original language – English or French – with a summary in the other. Comment on the series is welcome, and should be sent to the Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, 2, rue André-Pascal, 75775