Densities of Apes' Food Trees and Primates in the Petit Loango Researve, Gabon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

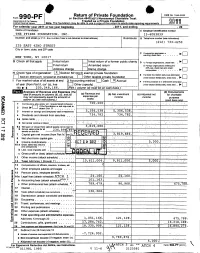

Return of Private Foundation CT' 10 201Z '

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirem M11 For calendar year 20 11 or tax year beainnina . 2011. and ending . 20 Name of foundation A Employer Identification number THE PFIZER FOUNDATION, INC. 13-6083839 Number and street (or P 0 box number If mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (212) 733-4250 235 EAST 42ND STREET City or town, state, and ZIP code q C If exemption application is ► pending, check here • • • • • . NEW YORK, NY 10017 G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D q 1 . Foreign organizations , check here . ► Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address chang e Name change computation . 10. H Check type of organization' X Section 501( exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation q 19 under section 507(b )( 1)(A) , check here . ► Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a60-month termination of year (from Part Il, col (c), line Other ( specify ) ---- -- ------ ---------- under section 507(b)(1)(B),check here , q 205, 8, 166. 16) ► $ 04 (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis) Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (The (d) Disbursements total of amounts in columns (b), (c), and (d) (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net for charitable may not necessanly equal the amounts in expenses per income income Y books purposes C^7 column (a) (see instructions) .) (cash basis only) I Contribution s odt s, grants etc. -

BRIGANCE Readiness Activities for Emerging K Children

BRIGANCE® Readiness Activities for Emerging K Children • Reading • Mathematics • Additional Support for Emerging K ©Curriculum Associates, LLC Click on a title to go directly to that page. Contents Mathematics BRIGANCE Activity Finder Number Concepts ............................ 89 Connecting to i-Ready Next Steps: Reading ...........iii Counting ................................... 98 Connecting to i-Ready Next Steps: Mathematics ........iv Reads Numerals ............................. 104 Additional Support for Emerging K .................. v Numeral Comprehension .......................110 Numerals in Sequence .........................118 Quantitative Concepts ........................ 132 BRIGANCE Readiness Activities Shape Concepts ............................ 147 Reading Joins Sets ................................. 152 Body Parts ................................... 1 Directional/Positional Concepts .................. 155 Colors ..................................... 12 Response to and Experience with Books ............ 21 Additional Support for Emerging K Prehandwriting .............................. 33 General Social and Emotional Development ......... 169 Visual Discrimination .......................... 38 Play Skills and Behaviors ...................... 172 Print Awareness and Concepts ................... 58 Initiative and Engagement Skills and Behaviors ....... 175 Reads Uppercase and Lowercase Letters ............ 60 Self-Regulation Skills and Behaviors ...............177 Prints Uppercase and Lowercase Letters in Sequence .. 66 -

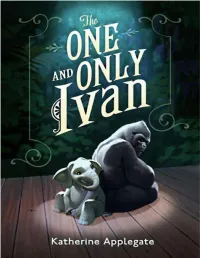

The ONE and ONLY Ivan

KATHERINE APPLEGATE The ONE AND ONLY Ivan illustrations by Patricia Castelao Dedication for Julia Epigraph It is never too late to be what you might have been. —George Eliot Glossary chest beat: repeated slapping of the chest with one or both hands in order to generate a loud sound (sometimes used by gorillas as a threat display to intimidate an opponent) domain: territory the Grunt: snorting, piglike noise made by gorilla parents to express annoyance me-ball: dried excrement thrown at observers 9,855 days (example): While gorillas in the wild typically gauge the passing of time based on seasons or food availability, Ivan has adopted a tally of days. (9,855 days is equal to twenty-seven years.) Not-Tag: stuffed toy gorilla silverback (also, less frequently, grayboss): an adult male over twelve years old with an area of silver hair on his back. The silverback is a figure of authority, responsible for protecting his family. slimy chimp (slang; offensive): a human (refers to sweat on hairless skin) vining: casual play (a reference to vine swinging) Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Epigraph Glossary hello names patience how I look the exit 8 big top mall and video arcade the littlest big top on earth gone artists shapes in clouds imagination the loneliest gorilla in the world tv the nature show stella stella’s trunk a plan bob wild picasso three visitors my visitors return sorry julia drawing bob bob and julia mack not sleepy the beetle change guessing jambo lucky arrival stella helps old news tricks introductions stella and ruby home -

Level 2 National the FANCY KRYMSUN 19.5

2019 AQHA WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP SHOW OPEN DIVISION QUALIFIERS If you have questions on your status as a qualifier, please email AQHA Show Events Coordinator Heidi Lane at [email protected]. As a reminder, entry forms and qualifier information will be sent to the email address on file for the current owner of the qualified horse. View more information about how to update or verify your email address under Latest News and Blogs at www.aqha.com/worldshow Owner - Alpha by First Name Horse Points Class Qualifier Type 2 N LAND & CATTLE COMPANY INC THE FANCY KRYMSUN 19.5 JUNIOR TRAIL - Level 2 National 2 N LAND & CATTLE COMPANY INC THE FANCY KRYMSUN 19.5 JUNIOR TRAIL - Level 3 National 2 N LAND & CATTLE COMPANY INC THE FANCY KRYMSUN 11 PERFORMANCE HALTER MARES- Level 2 National 2 N LAND & CATTLE COMPANY INC THE FANCY KRYMSUN 11 PERFORMANCE HALTER MARES- Level 3 National 6V LIVESTOCK LLC DIAMOND STYLIN SHINE 17.5 JUNIOR DALLY TEAM ROPING-HEELING - LV2 National 6V LIVESTOCK LLC DIAMOND STYLIN SHINE 17.5 JUNIOR DALLY TEAM ROPING-HEELING - LV3 National 6V LIVESTOCK LLC DIAMOND STYLIN SHINE 2.5 PERFORMANCE HALTER STALLIONS - Level 2 National 6V LIVESTOCK LLC DIAMOND STYLIN SHINE 2.5 PERFORMANCE HALTER STALLIONS - Level 3 National 6V LIVESTOCK LLC LEOS SILVER SHINE 18.5 JUNIOR DALLY TEAM ROPING-HEADING - LV2 National 6V LIVESTOCK LLC LEOS SILVER SHINE 18.5 JUNIOR DALLY TEAM ROPING-HEADING - LV3 National 70 RANCH PERFORMANCE HORSES DEZ SHE BOON 11 SENIOR RANCH RIDING - LEVEL 2 National 70 RANCH PERFORMANCE HORSES DEZ SHE BOON 11 SENIOR RANCH RIDING - -

THE OFFICIAL VOL XLVII NUMBER 1 Jan/Feb/Mar 2012 BULLETIN Ankhu Basenjis Announces

THE OFFICIAL VOL XLVII NUMBER 1 Jan/Feb/Mar 2012 BULLETIN Ankhu Basenjis Announces.... PUPPIES born November 29, 2011! Sire GCh DC Jerlin's Our Zuri Pupin MC, LCX, TT, SGRC2, ORC, LCM, VFCh, VB Dam Four-Time Group Winning Ch. Ankhu Promises in the Dark Best wishes for years of fun & success with their boys to Ankhu Basenjis Carrie & Mike Jones Clay Bunyard & Terry Fiedler www.ankhubasenjis.com Jan Feb Mar 2012 In This Issue ULLETIN INSIDE B The Official Publication of the Basenji Club of America, Inc. FEATURES Foundation Stock 16 (USPS 707-210) ISSN 1077-808x Introduction by Pamela Geoffroy Is Published Quarterly Avongara Akua 17 March, June, September & December Avongara Makala 18 By the Basenji Club of America, Inc. Avongara Naziki 19 Janet Ketz, Secretary Avongara Nilli 20 34025 West River Road, Wilmington, IL 60481 Founder Population 23 Periodical Postage Paid at Kerrville, TX How Many Founders Does It Take To Make A Breed? and at Additional Mailing Offices. Dr. Jo Thompson Memo to Myself 28 POSTMASTER: Reprint from April 1975 Bulletin – R Dwinnells Send address changes to: Basenji Club of America, Inc. Mary Lou Kenworthy Janet Ketz, Secretary 34025 West River Road INSIDE Wilmington, IL 60481 President’s Message 5 Copyright © 2011 Editor’s Message 4 by the Basenji Club of America, Inc. Letter to the Editor 6 All Rights Reserved. BCOA Financials 8 Material may be reprinted without written AKC Delegate 7 permission in publications of BCOA Affiliate Clubs only. CLUB NEWS Opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors. Basenji Club of Cincinnati 13 Articles & opinions do not necessarily express or represent the Basenji Club of Northern California 12 policies and opinions of the Basenji Club of America, Inc. -

Aus Girls Top 25 Lc, 1 Jan to 31 Oct 2010

Australian Girls Top 25 Short Course 1st January to 31st October 2010 email any errors or omissions to [email protected] FPS Female 13 & Under 50 Free 1 26.57L 712F Brianna Throssell 13 CPER 27/01/2010 2010 SunSmart Open Swimming Championships 2 26.71 L 701F Georgia Miller 13 WRAQ 4/01/2010 2010 NSW State 13-18 Years Age Championships 3 26.79 L 695F Ami Matsuo 13 CARL 5/04/2010 2010 Australian Age Championships 4 26.81 L 693F Jemma Schlicht 12 MLC 5/04/2010 2010 Australian Age Championships 5 26.86L 690F Brittany McEvoy 13 STHPT 5/04/2010 2010 Australian Age Championships 6 27.12 L 670F Gabrielle Turnbull 13 SLCA 5/04/2010 2010 Australian Age Championships 7 27.24 L 661F Jasmine Tong 13 MARLI 4/01/2010 2010 NSW State 13-18 Years Age Championships 8 27.36 L 652P Tatum Marais 13 JAMBO 5/04/2010 2010 Australian Age Championships 9*F 27.49 L 643 Tayla Brunt 13 STHPT 5/04/2010 2010 Australian Age Championships 9*F 27.49 L 643 Candice Wall 13 ARE 9/10/2010 2010 City of Perth Classic LC Swim Meet 11 27.56L 638F Hazel Son 12 SSW 5/04/2010 2010 Australian Age Championships 12 27.71 L 628P Georgia Tsebelis 13 TRL 5/04/2010 2010 Australian Age Championships 13 27.74 L 626F Olivia Fryer 13 MTAN 6/02/2010 2010 MSW Speedo Sprint Series Heats 14 27.75 L 625P Emma Morgan 13 WILB 4/01/2010 2010 NSW State 13-18 Years Age Championships 15 27.76 L 625F Brooke Krause 13 QLD 6/06/2010 School Sport Australia Swimming Championships 16 27.80 L 622P Ayu Barry 13 TELO 5/04/2010 2010 Australian Age Championships 17 27.84L 619F Lauren Rettie 13 RIVER 11/09/2010 -

98.6: a Creative Commonality

CONTENT 1 - 2 exibition statement 3 - 18 about the chimpanzees and orangutans 19 resources 20 educational activity 21-22 behind the scenes 23 installation images 24 walkthrough video / flickr page 25-27 works in show 28 thank you EXHIBITION STATEMENT Humans and chimpanzees share 98.6% of the same DNA. Both species have forward-facing eyes, opposing thumbs that accompany grasping fingers, and the ability to walk upright. Far greater than just the physical similarities, both species have large brains capable of exhibiting great intelligence as well as an incredible emotional range. Chimpanzees form tight social bonds, especially between mothers and children, create tools to assist with eating and express joy by hugging and kissing one another. Over 1,000,000 chimpanzees roamed the tropical rain forests of Africa just a century ago. Now listed as endangered, less than 300,000 exist in the wild because of poaching, the illegal pet trade and habitat loss due to human encroachment. Often, chimpanzees are killed, leaving orphans that are traded and sold around the world. Thanks to accredited zoos and sanctuaries across the globe, strong conservation efforts and programs exist to protect and manage populations of many species of the animal kingdom, including the great apes - the chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan and bonobo. In the United States, institutions such as the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) and the Species Survival Plan (SSP) work together across the nation in a cooperative effort to promote population growth and ensure the utmost care and conditions for all species. Included in the daily programs for many species is what’s commonly known as “enrichment”–– an activity created and employed to stimulate and pose a challenge, such as hiding food and treats throughout an enclosure that requires a search for food, sometimes with a problem-solving component. -

Africa-Adventure.Pdf

Africa! Adventure At a glance Participants will explore the different habitats of the African continent and will learn about some of the animals that live there. Time requirement Goal(s) 1.5 hour program Insert general goals Group size and grade(s) Objective(s) 8-25 participants x Learn about the kinds of habitats Due to the family nature of this class, found in Africa participant ages will vary (infant to x Learn about African animals and grandparent age range) their adaptations Materials Theme Lion mask craft materials Animals that live on the African continent Hike Helper cards have special adaptations that let them Radio survive in the different habitats. Black first aid bag Maasai lion bracelet (for you to wear during Sub-themes the program – please put it back in the bag 1. Every habitat has its own food web. after the program for the next instructor) 2. Every continent has many different types of habitat. Africa! Adventure, July 2013 Page 1 of 13 Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden Background there. Camouflaged coloration, stealthy Africa is made up of mostly 3 biomes: savanna, hunting styles, speed or cooperative hunting desert, and rainforest. Each is host to a unique strategies often lead to success when hunting variety of wildlife with adaptations especially individuals within the many herds of suited to the habitats found there. herbivores. Savanna One of the most well known African Savannas is The African Savanna biome is a tropical the Serengeti. This grassland boasts the largest grassland that can be found in the African diversity of hoofed animals in the world countries of Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Cote including antelopes, wildebeest, buffalos, D'ivore, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria, zebras, and rhinoceros. -

Freedom of the Press 2009

Freedom of the Press 2009 FURTHER DECLINES IN GLOBAL MEDIA INDEPENDENCE Selected data from Freedom House’s annual survey of press freedom Acknowledgments Freedom of the Press 2009 could not have been completed without the contributions of numerous Freedom House staff and consultants. The following section, entitled “The Survey Team,” contains a detailed list of writers without whose efforts this project would not have been possible. Karin Deutsch Karlekar, a senior researcher at Freedom House, served as managing editor of this year’s survey. Extensive research, editorial, and administrative assistance was provided by Denelle Burns, as well as by Sarah Cook, Tyler Roylance, Elizabeth Floyd, Joanna Perry, Joshua Siegel, Charles Liebling, and Aidan Gould. Overall guidance for the project was provided by Arch Puddington, director of research, and by Christopher Walker, director of studies. We are grateful for the insights provided by those who served on this year’s review team, including Freedom House staff members Arch Puddington, Christopher Walker, Karin Deutsch Karlekar, Sarah Cook, and Tyler Roylance. In addition, the ratings and narratives were reviewed by a number of Freedom House staff based in our overseas offices. This report also reflects the findings of the Freedom House study Freedom in the World 2009: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties. Statistics on internet usage were taken from www.internetworldstats.com. This project was made possible by the contributions of the Asia Vision Foundation, F. M. Kirby, Free Voice, Freedom Forum, The Hurford Foundation, John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Lilly Endowment Inc., The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, the National Endowment for Democracy, The Nicholas B. -

Download PDF -. | Official Gazette

FederalRepublic of Nigeria . | Official Gazette No.|37 Lagos - lith July, 1974 Vol. 61 Ln CONTENTS “Page- | . “Page - Movements ofOfficers 1094-1102 Federal GovernmentScholarship and Bursary ( Awards for 1974 75—Succetl Candi ‘Ministry: of Defence—Nigerian Navy— ‘+ dates .. tet ‘107.37 Promotions . 1103 Insurance Company which has been registered . “Tenders . 1138-40 as an Insurer under'the Insurance .Com- _ panies Act 1961 and is therefore permitted Vacancies - 1140-48 to transact Insurance Business in Nigeria .. 1103 oo Customs andExcise Nigeria—Sale ofGoods 1148 Application for Gas Pipeline Licence . 1103-4 , Public Notice No. 96—Nigerian Yeast Com- Land required for the Service of the Federal ‘ pany Limited—Date of Meeting of Credi- Military Government . 1104-5 tors... 1148 RateofRoyaltyonTin = =, .” cose 1105 ; LoneofLocalPurchase Orders ss 1105 . ., , aPayable Orders 1105 - Inpex To Lecan.Nortices In SUPPLEMENT LossofIndent . - oe . , 1105-6 L.N. No. - Short Title . Page Central’ Bank of Nigeria-~Board Resolutions - - — Decree No. 28—Income ‘Tax (Miscel- -. atitsMeeting of "Fhureday, 27th June, 1974 1106 Janeous Provisions) Decree 1974. .. A135 - West-"Africa Examination — Board—Royal —_ DecreeNo. 29—Robbery and Firearms Societyof Health—Health Sisters’‘Diploma (Special Provisions) (Amendment) "Examination Result 1974... : (No. 2) Décree1974 A139 sangeet 1094 ‘ OFFICIAL GAZETTE No. 37, Vol. 61 Government Notice No. 988 _ NEW APPOINTMENTS ANDOTHER STAFF CHANGES The ‘owing are notified for general information :— NEW APPOINTMENTS 7 Department; Name Appointment Date of _ . Appointment Ministry of Agriculture Emode, Miss M. .. Typist, Grade III 2-1-74 and Natural Ri , | , _ Ministry of Communi- Bello, P. A. + Postal Officer .. 0 | 17-7-73 cations Conweh, C. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Teaching Guide Discussion Questions About the Book

By Katherine Applegate TEACHING GUIDE ABOUT THE BOOK van, an adult male silverback gorilla, has been living in captivity for 27 years, most of that time on display at the Exit 8 Big Top Mall and Video Arcade, along with Stella, Ia wise older elephant, and Bob, a sassy stray dog. Julia, the janitor’s daughter, helps Ivan with his artistic efforts. But when Mack, the owner of the mall, introduces a baby elephant named Ruby, Ivan sees his captivity for what it is. Realizing that Ruby needs more freedom, Ivan assumes his rightful place as a leader and secures a better future for himself and his friends. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. What does Ivan mean when he says, “In my size 3. Discuss the special bond between Julia and Ivan. humans see a test of themselves” (p. 4), and “I am too Why is she different from all the other children who much gorilla and not enough human” (p. 7)? Why come to see his shows? Why do people pay for Ivan’s does the sign for the Big Top Mall show Ivan as angry drawings if they don’t recognize what he has drawn? and fierce? Why doesn’t Ivan express any anger in the Why is Ivan’s art important to Mack? Why is it beginning of the story? CCSS 4–6.RL.4, CCSS 4–6.RL.3 important to Julia? CCSS 4.RL.6 2. What are the characteristics of Stella and Bob that 4. What is the importance of the television in Ivan’s cage? make Ivan call them his best friends? Why is each of What does he learn from watching the television? them important to Ivan? What do Ivan and Stella have Why does he like Westerns, and what does he learn in common? How are they alike, and how are they from the nature shows? What do you learn from different? What does Stella mean when she says, “Old television? What would you say is the most important age is a powerful disguise” (p.