Illicit Financial Flows and the Illegal Trade in Great Apes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10 Sota3 Chapter 7 REV11

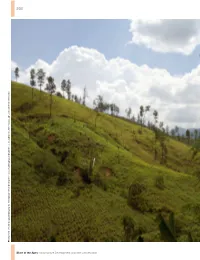

200 Until recently, quantifying rates of tropical forest destruction was challenging and laborious. © Jabruson 2017 (www.jabruson.photoshelter.com) forest quantifying rates of tropical Until recently, Photo: State of the Apes Infrastructure Development and Ape Conservation 201 CHAPTER 7 Mapping Change in Ape Habitats: Forest Status, Loss, Protection and Future Risk Introduction This chapter examines the status of forested habitats used by apes, charismatic species that are almost exclusively forest-dependent. With one exception, the eastern hoolock, all ape species and their subspecies are classi- fied as endangered or critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (IUCN, 2016c). Since apes require access to forested or wooded land- scapes, habitat loss represents a major cause of population decline, as does hunting in these settings (Geissmann, 2007; Hickey et al., 2013; Plumptre et al., 2016b; Stokes et al., 2010; Wich et al., 2008). Until recently, quantifying rates of trop- ical forest destruction was challenging and laborious, requiring advanced technical Chapter 7 Status of Apes 202 skills and the analysis of hundreds of satel- for all ape subspecies (Geissmann, 2007; lite images at a time (Gaveau, Wandono Tranquilli et al., 2012; Wich et al., 2008). and Setiabudi, 2007; LaPorte et al., 2007). In addition, the chapter projects future A new platform, Global Forest Watch habitat loss rates for each subspecies and (GFW), has revolutionized the use of satel- uses these results as one measure of threat lite imagery, enabling the first in-depth to their long-term survival. GFW’s new analysis of changes in forest availability in online forest monitoring and alert system, the ranges of 22 great ape and gibbon spe- entitled Global Land Analysis and Dis- cies, totaling 38 subspecies (GFW, 2014; covery (GLAD) alerts, combines cutting- Hansen et al., 2013; IUCN, 2016c; Max Planck edge algorithms, satellite technology and Insti tute, n.d.-b). -

Identification of Subspecies and Parentage Relationship by Means of DNA Fingerprinting in Two Exemplary of Pan Troglodytes (Blumenbach, 1775) (Mammalia Hominidae)

Biodiversity Journal , 2018, 9 (2): 107–114 DOI: 10.31396/Biodiv.Jour.2018.9.2.107.114 Identification of subspecies and parentage relationship by means of DNA fingerprinting in two exemplary of Pan troglodytes (Blumenbach, 1775) (Mammalia Hominidae) Viviana Giangreco 1, Claudio Provito 1, Luca Sineo 2, Tiziana Lupo 1, Floriana Bonanno 1 & Stefano Reale 1* 1Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della Sicilia “A. Mirri”, Via G. Marinuzzi 3, 90129 Palermo, Italy 2Biologia animale e Antropologia, Dip. STEBICEF, Via Archirafi 18, 90123 Palermo, Italy *Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Four chimpanzee subspecies (Mammalia Hominidae) are commonly recognised: the West - ern Chimpanzee, P. troglodytes verus (Schwarz, 1934), the Nigeria-Cameroon Chim - panzee, P. troglodytes ellioti, the Central Chimpanzee, P. troglodytes troglodytes (Blumenbach, 1799), and the Eastern Chimpanzee, P. troglodytes schweinfurthii (Giglioli, 1872). Recent studies on mitochondrial DNA show the incorporation of P. troglodytes schweinfurthii in P. troglodytes troglodytes , suggesting the existence of only two sub - species: P. troglodytes troglodytes in Central and Eastern Africa and P. troglodytes verus- P. troglodytes ellioti in West Africa. The aim of the present study is twofold: first, to identify the correct subspecies of two chimpanzee samples collected in a Biopark structure in Carini (Sicily, Italy), and second, to verify whether there was a kinship relationship be - tween the two samples through techniques such as DNA barcoding and microsatellite analysis. DNA was extracted from apes’ buccal swabs, the cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (COI) gene was amplified using universal primers, then purified and injected into capillary electrophoresis Genetic Analyzer ABI 3130 for sequencing. The sequence was searched on the NCBI Blast database. -

Return of Private Foundation CT' 10 201Z '

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirem M11 For calendar year 20 11 or tax year beainnina . 2011. and ending . 20 Name of foundation A Employer Identification number THE PFIZER FOUNDATION, INC. 13-6083839 Number and street (or P 0 box number If mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (212) 733-4250 235 EAST 42ND STREET City or town, state, and ZIP code q C If exemption application is ► pending, check here • • • • • . NEW YORK, NY 10017 G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D q 1 . Foreign organizations , check here . ► Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address chang e Name change computation . 10. H Check type of organization' X Section 501( exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation q 19 under section 507(b )( 1)(A) , check here . ► Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a60-month termination of year (from Part Il, col (c), line Other ( specify ) ---- -- ------ ---------- under section 507(b)(1)(B),check here , q 205, 8, 166. 16) ► $ 04 (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis) Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (The (d) Disbursements total of amounts in columns (b), (c), and (d) (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net for charitable may not necessanly equal the amounts in expenses per income income Y books purposes C^7 column (a) (see instructions) .) (cash basis only) I Contribution s odt s, grants etc. -

Ebola & Great Apes

Ebola & Great Apes Ebola is a major threat to the survival of African apes There are direct links between Ebola outbreaks in humans and the contact with infected bushmeat from gorillas and chimpanzees. In the latest outbreak in West Africa, Ebola claimed more than 11,000 lives, but the disease has also decimated great ape populations during previous outbreaks in Central Africa. What are the best strategies for approaching zoonotic diseases like Ebola to keep both humans and great apes safe? What is Ebola ? Ebola Virus Disease, formerly known as Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever, is a highly acute, severe, and lethal disease that can affect humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas. It was discovered in 1976 in the Democratic Republic of Congo and is a Filovirus, a kind of RNA virus that is 50-100 times smaller than bacteria. • The initial symptoms of Ebola can include a sudden fever, intense weakness, muscle pain and a sore throat, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Subsequent stages include vomiting, diarrhoea and, in some cases, both internal and external bleeding. • Though it is believed to be carried in bat populations, the natural reservoir of Ebola is unknown. A reservoir is the long-term host of a disease, and these hosts often do not contract the disease or do not die from it. • The virus is transmitted to people from wild animals through the consumption and handling of wild meats, also known as bushmeat, and spreads in the human population via human-to-human transmission through contact with bodily fluids. • The average Ebola case fatality rate is around 50%, though case fatality rates have varied from 25% to 90%. -

BRIGANCE Readiness Activities for Emerging K Children

BRIGANCE® Readiness Activities for Emerging K Children • Reading • Mathematics • Additional Support for Emerging K ©Curriculum Associates, LLC Click on a title to go directly to that page. Contents Mathematics BRIGANCE Activity Finder Number Concepts ............................ 89 Connecting to i-Ready Next Steps: Reading ...........iii Counting ................................... 98 Connecting to i-Ready Next Steps: Mathematics ........iv Reads Numerals ............................. 104 Additional Support for Emerging K .................. v Numeral Comprehension .......................110 Numerals in Sequence .........................118 Quantitative Concepts ........................ 132 BRIGANCE Readiness Activities Shape Concepts ............................ 147 Reading Joins Sets ................................. 152 Body Parts ................................... 1 Directional/Positional Concepts .................. 155 Colors ..................................... 12 Response to and Experience with Books ............ 21 Additional Support for Emerging K Prehandwriting .............................. 33 General Social and Emotional Development ......... 169 Visual Discrimination .......................... 38 Play Skills and Behaviors ...................... 172 Print Awareness and Concepts ................... 58 Initiative and Engagement Skills and Behaviors ....... 175 Reads Uppercase and Lowercase Letters ............ 60 Self-Regulation Skills and Behaviors ...............177 Prints Uppercase and Lowercase Letters in Sequence .. 66 -

The ONE and ONLY Ivan

KATHERINE APPLEGATE The ONE AND ONLY Ivan illustrations by Patricia Castelao Dedication for Julia Epigraph It is never too late to be what you might have been. —George Eliot Glossary chest beat: repeated slapping of the chest with one or both hands in order to generate a loud sound (sometimes used by gorillas as a threat display to intimidate an opponent) domain: territory the Grunt: snorting, piglike noise made by gorilla parents to express annoyance me-ball: dried excrement thrown at observers 9,855 days (example): While gorillas in the wild typically gauge the passing of time based on seasons or food availability, Ivan has adopted a tally of days. (9,855 days is equal to twenty-seven years.) Not-Tag: stuffed toy gorilla silverback (also, less frequently, grayboss): an adult male over twelve years old with an area of silver hair on his back. The silverback is a figure of authority, responsible for protecting his family. slimy chimp (slang; offensive): a human (refers to sweat on hairless skin) vining: casual play (a reference to vine swinging) Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Epigraph Glossary hello names patience how I look the exit 8 big top mall and video arcade the littlest big top on earth gone artists shapes in clouds imagination the loneliest gorilla in the world tv the nature show stella stella’s trunk a plan bob wild picasso three visitors my visitors return sorry julia drawing bob bob and julia mack not sleepy the beetle change guessing jambo lucky arrival stella helps old news tricks introductions stella and ruby home -

Proposal for Inclusion of the Chimpanzee

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.1 25 May 2017 SPECIES Original: English 12th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Manila, Philippines, 23 - 28 October 2017 Agenda Item 25.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) ON APPENDIX I AND II OF THE CONVENTION Summary: The Governments of Congo and the United Republic of Tanzania have jointly submitted the attached proposal* for the inclusion of the Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) on Appendix I and II of CMS. *The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CMS Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) ON APPENDICES I AND II OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A: PROPOSAL Inclusion of Pan troglodytes in Appendix I and II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. B: PROPONENTS: Congo and the United Republic of Tanzania C: SUPPORTING STATEMENT 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Mammalia 1.2 Order: Primates 1.3 Family: Hominidae 1.4 Genus, species or subspecies, including author and year: Pan troglodytes (Blumenbach 1775) (Wilson & Reeder 2005) [Note: Pan troglodytes is understood in the sense of Wilson and Reeder (2005), the current reference for terrestrial mammals used by CMS). -

Exploration IV

Tab Table of Contents I. Foundation…………………………………………………………………………………..…………………..2 II. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 III. Snapshot ........................................................................................................................ 7 Exploration IV. Framework ..................................................................................................................... 8 V. Ideas for Learning Centers ............................................................................................. 57 One: Our VI. Texts ............................................................................................................................ 78 VII. Inquiry and Critical Thinking Questions for Texts .......................................................... 81 VIII. Weekly Planning Template ........................................................................................... 84 Community IX. Documenting Learning……………………………………………………………………………………..89 X. Supporting Resources .................................................................................................... 95 Interdisciplinary Instructional XI. Appendices ................................................................................................................... 97 Guidance A. Toilet Learning……………………………………………………………………………………………………….97 B. Handwashing……………………………………………………………………………………………99 C. Center Planning Form……………………………………………………………………………….100 D. -

Level 2 National the FANCY KRYMSUN 19.5

2019 AQHA WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP SHOW OPEN DIVISION QUALIFIERS If you have questions on your status as a qualifier, please email AQHA Show Events Coordinator Heidi Lane at [email protected]. As a reminder, entry forms and qualifier information will be sent to the email address on file for the current owner of the qualified horse. View more information about how to update or verify your email address under Latest News and Blogs at www.aqha.com/worldshow Owner - Alpha by First Name Horse Points Class Qualifier Type 2 N LAND & CATTLE COMPANY INC THE FANCY KRYMSUN 19.5 JUNIOR TRAIL - Level 2 National 2 N LAND & CATTLE COMPANY INC THE FANCY KRYMSUN 19.5 JUNIOR TRAIL - Level 3 National 2 N LAND & CATTLE COMPANY INC THE FANCY KRYMSUN 11 PERFORMANCE HALTER MARES- Level 2 National 2 N LAND & CATTLE COMPANY INC THE FANCY KRYMSUN 11 PERFORMANCE HALTER MARES- Level 3 National 6V LIVESTOCK LLC DIAMOND STYLIN SHINE 17.5 JUNIOR DALLY TEAM ROPING-HEELING - LV2 National 6V LIVESTOCK LLC DIAMOND STYLIN SHINE 17.5 JUNIOR DALLY TEAM ROPING-HEELING - LV3 National 6V LIVESTOCK LLC DIAMOND STYLIN SHINE 2.5 PERFORMANCE HALTER STALLIONS - Level 2 National 6V LIVESTOCK LLC DIAMOND STYLIN SHINE 2.5 PERFORMANCE HALTER STALLIONS - Level 3 National 6V LIVESTOCK LLC LEOS SILVER SHINE 18.5 JUNIOR DALLY TEAM ROPING-HEADING - LV2 National 6V LIVESTOCK LLC LEOS SILVER SHINE 18.5 JUNIOR DALLY TEAM ROPING-HEADING - LV3 National 70 RANCH PERFORMANCE HORSES DEZ SHE BOON 11 SENIOR RANCH RIDING - LEVEL 2 National 70 RANCH PERFORMANCE HORSES DEZ SHE BOON 11 SENIOR RANCH RIDING - -

Academic All-American Award Recipients 2019 AAU Volleyball

2019 AAU Volleyball Academic All-American Award Recipients The AAU Volleyball National Executive Committee is proud to announce the selections for the 2019 AAU Volleyball Academic All American Award. Created in 2013, the award recognizes student-athletes for their excellence in academics as well as athletics. All recipients attended high school during the 2018-2019 school year and participated in the 46th AAU Junior National Volleyball Championships. First Name Last Name Team Grade High School State Kylie Adams 17 White 11th Grade Victor J. Andrew High School IL Ellyn Adams Coast United 16-1 10th Grade Socastee High School SC Cassidy Adams 16 Crimson 10th Grade Newark Community High School IL Emily Ah Leong 17 Tigers Wild Gold 11th Grade W.E. Boswell High School TX Kayelin Aikens Union 15-2 Asics 9th Grade Christian Academy of Louisville KY Olivia Albers 16-4 10th Grade Spring Lake Park High School MN Emily Alberts Elite 152 9th Grade Brebeuf Jesuit Preparatory School, Indianapolis, IN IN Annika Altekruse 17 Pre 11th Grade Metea Valley High School IL Simara Amador 15-1 9th Grade Eagan High School MN Ariel Amaya 16 Elite 10th Grade Plainfield North IL Morgan Amos Waves 10th Grade Mount Hebron High School MD Jill Amsler Alliance 17- Ren 11th Grade Franklin High School TN Alexa Anderson 15X Premier 9th Grade Smoky Mountain High School NC Nathaniel Cain Anderson Chicago Elite 15 Elite 10th Grade Lincoln Park High School IL Alexis Andrews 15 Gold 9th Grade Stratford High School TX Frida Anguiano 18 Coco 12th Grade Oak Mountain High School -

National Conference

NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE POPULAR CULTURE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN CULTURE ASSOCIATION In Memoriam We honor those members who passed away this last year: Mortimer W. Gamble V Mary Elizabeth “Mery-et” Lescher Martin J. Manning Douglas A. Noverr NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE POPULAR CULTURE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN CULTURE ASSOCIATION APRIL 15–18, 2020 Philadelphia Marriott Downtown Philadelphia, PA Lynn Bartholome Executive Director Gloria Pizaña Executive Assistant Robin Hershkowitz Graduate Assistant Bowling Green State University Sandhiya John Editor, Wiley © 2020 Popular Culture Association Additional information about the PCA available at pcaaca.org. Table of Contents President’s Welcome ........................................................................................ 8 Registration and Check-In ............................................................................11 Exhibitors ..........................................................................................................12 Special Meetings and Events .........................................................................13 Area Chairs ......................................................................................................23 Leadership.........................................................................................................36 PCA Endowment ............................................................................................39 Bartholome Award Honoree: Gary Hoppenstand...................................42 Ray and Pat Browne Award -

THE OFFICIAL VOL XLVII NUMBER 1 Jan/Feb/Mar 2012 BULLETIN Ankhu Basenjis Announces

THE OFFICIAL VOL XLVII NUMBER 1 Jan/Feb/Mar 2012 BULLETIN Ankhu Basenjis Announces.... PUPPIES born November 29, 2011! Sire GCh DC Jerlin's Our Zuri Pupin MC, LCX, TT, SGRC2, ORC, LCM, VFCh, VB Dam Four-Time Group Winning Ch. Ankhu Promises in the Dark Best wishes for years of fun & success with their boys to Ankhu Basenjis Carrie & Mike Jones Clay Bunyard & Terry Fiedler www.ankhubasenjis.com Jan Feb Mar 2012 In This Issue ULLETIN INSIDE B The Official Publication of the Basenji Club of America, Inc. FEATURES Foundation Stock 16 (USPS 707-210) ISSN 1077-808x Introduction by Pamela Geoffroy Is Published Quarterly Avongara Akua 17 March, June, September & December Avongara Makala 18 By the Basenji Club of America, Inc. Avongara Naziki 19 Janet Ketz, Secretary Avongara Nilli 20 34025 West River Road, Wilmington, IL 60481 Founder Population 23 Periodical Postage Paid at Kerrville, TX How Many Founders Does It Take To Make A Breed? and at Additional Mailing Offices. Dr. Jo Thompson Memo to Myself 28 POSTMASTER: Reprint from April 1975 Bulletin – R Dwinnells Send address changes to: Basenji Club of America, Inc. Mary Lou Kenworthy Janet Ketz, Secretary 34025 West River Road INSIDE Wilmington, IL 60481 President’s Message 5 Copyright © 2011 Editor’s Message 4 by the Basenji Club of America, Inc. Letter to the Editor 6 All Rights Reserved. BCOA Financials 8 Material may be reprinted without written AKC Delegate 7 permission in publications of BCOA Affiliate Clubs only. CLUB NEWS Opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors. Basenji Club of Cincinnati 13 Articles & opinions do not necessarily express or represent the Basenji Club of Northern California 12 policies and opinions of the Basenji Club of America, Inc.