Coordinates of Features on the Galilean Satellites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Document Overview 1.2 Software Overview

625-645-234011, Rev. A TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Document Overview 1.2 Software Overview 1.3 System Hardware/Software Requirements 1.3.1 SUN 1.3.2 Windows 3.1 or Macintosh 1.4 Packaging 1.4.1 MIRAGE System Files 1.4.2 MIRAGE Data Files 1.4.3 Sequence Delivery Directories 1.5 Typographical Conventions 2 SETTING UP TO RUN MIRAGE 2.1 Obtaining a Unix Account 2.2 Installing the X terminal Server 2.2.1 MacIntosh 2.2.2 Windows 3.1 2.2.3 What's your IP Address? 2.3 Starting and Exiting MIRAGE 2.3.1 From Donatello 2.3.2 From a MAC 2.3.3 From Windows 2.3.4 From a Sun Workstation (e.g. POINTER) 3 MIRAGE INTERFACE BASICS 3.1 The MIRAGE Display 3.1.1 Command Pane 3.1.2 History Pane 3.1.3 Display Work Area 3.1.4 The Legend 3.2 Configuring MIRAGE 3.2.1 Changing Legends 3.2.2 Zooming and Scaling 625-645-234011, Rev. A 3.2.3 Vertical Ruler 3.3 MIRAGE Commands 3.3.1 Aborting Commands 3.3.2 Command Help 3.3.3 Mouse Command Sets 3.4 The MIRAGE Menus 4 MODELING IN MIRAGE 4.1 Multi Use Buffer 4.1.1 Buffer High and Low Water Marks 4.1.2 Filling the Buffer 4.1.3 Draining the Buffer 4.1.4 Modeling the Effects of Real Time Activities on the MUB 4.1.5 Modeling the Effect of Buffer Dump to Tape on the MUB 4.1.6 Modeling the Effect of Playback on the MUB 4.1.7 Modeling the Effect of Telemetry on the MUB 4.1.8 User Control of the MUB Level 4.2 Priority Buffer 4.3 DMS 4.4 Running the Models 4.5 How Modeling Results are Displayed 4.6 OAPEL-level Resource Conflict Checking 4.7 How OAPEL-level Conflict Checking Results are Displayed 5 USING MIRAGE 5.1 Starting MIRAGE 5.1.1 Miscellaneous (But Useful) Commands 5.1.2 Moving around the screen 5.2 Create OAPEL 5.2.1 Activity ID Usage 5.2.2 Adding PAs to an OAPEL 5.3 Edit OAPEL 5.4 Create PA 5.5 Edit PA 625-645-234011, Rev. -

JUPITERJUPITER La Planète Ses Anneaux Son Système Satellitaire Ses Principaux Satellites (Détails) La Mission Galileo Iconographie, Photos Et Additifs

JUPITERJUPITER La planète Ses anneaux Son système satellitaire Ses principaux satellites (détails) La mission Galileo Iconographie, photos et additifs GAP 47 • Olivier Sabbagh • Février 2015 / Révision Mai 2019 Jupiter, la plus grosse planète du système solaire I – Mythologie, historique, généralités Jupiter, en latin Jupiter (génitif Jovis), est le dieu romain qui gouverne la terre et le ciel, ainsi que tous les êtres vivants s'y trouvant. Il est aussi le maître des autres dieux. Il est originellement un dieu du ciel, caractéristique que l'on retrouve dans son association aux présages célestes liés aux pratiques divinatoires des prêtres de Rome. Il a pour attributs l'aigle et le foudre (nom masculin dans ce cas). Il est assimilé à Zeus chez les Grecs et à Dyaus Pitar, parfois Shiva, chez les Hindous. Les Romains finirent par associer le dieu Jupiter à son équivalent grec Zeus, même si les deux dieux se distinguent d'abord très nettement. Dans la tradition littéraire romaine, la représentation de Zeus se superpose à celle de Jupiter, au point que les deux dieux finissent par être confondus tant par les mythes que l'iconographie. C'est pour cela que Jupiter, jusqu'alors quasiment privé de mythologie ou de liens de parenté, se voit attribuer les caractéristiques mythologiques du dieu grec Zeus. Ainsi, Jupiter est marié à sa sœur, Junon. Pourtant, il est intéressant de constater que le culte de Jupiter avant l'influence de son homologue grec met en évidence un dieu radicalement différent. Parmi les divinités, Jupiter tenait toujours le plus haut rang. L'aigle, qui plane en haut des cieux et fond comme la foudre sur sa proie, était son oiseau favori. -

O Lunar and Planetary Institute Provided by the NASA Astrophysics Data System 456 LPS XXVII

LPS XXVII 455 GALILEO SSI OBSERVATION PLANS FOR CALLISTO AND EUROPA, R. Greeleyl, K. ~enderl,R. Sullivan1, R. ~appalardo~,K. Homanl, l~rizonaState University, Tempe, AZ, 85287, 2Brown University, Providence, RI, 02912 On December 7, 1995, the Galileo spacecraft successfully entered orbit around Jupiter, beginning its two-year mission to explore the planet's atmosphere, family of satellites, ring system, and magnetospheric environment. here we present an update to previously published work[l] of the solid-sate imaging (SSI) plans for observing Callisto and Europa during Galileo's two-year mission. Due to a problem with the on-board tape-recorder during Jupiter approach, a unique 700 rn/pixel mosaic of the south pole of Europa was canceled, along with high resolution imaging of 10. As a consequence of the tape recorder anomaly and revised rules for its use, approximately 16% less tape capacity will be available for storing SSI images and other data throughout the mission. The surface of Callisto is characterized by globally extensive impact-cratered plains and several large multi-ring structures. Abundant impact craters indicate the surface of Callisto is the oldest preserved of the four Galilean satellites. Callisto's bulk density of 1.86 g/cm3 makes it the least dense and iciest of the Galilean satellites[2]. Although Callisto's ancient surface is relatively simple when compared to the other Galilean satellites, it represents an important end-member which provides a key for studying the early Jovian environment as well as impact cratering and other fundamental processes on icy bodies. The present Galileo SSI imaging plan includes 163 pictures at Callisto. -

B. Geologische Karten Und Statistik Großer Einschlagsstrukturen

B. Geologische Karten und Statistik großer Einschlagsstrukturen In den folgenden Abbildungen und Tabellen sind Kartierungen, Lage und Durchmesser großer Impaktstrukturen - Palimpseste und Ringbecken - enthalten, die in den weitaus meisten F¨allen bereits stark abgetragen und daher schwer erkennbar sind. Identifizierung, Kartierung und Gr¨oßenverteilung wurden im Detail in Abschnitt 8.6.7 diskutiert. Die Lage der einzelnen kar- tierten Gebiete geht aus Bild 8.1 in Abschnitt 8.1 hervor. Da der Großteil dieser Strukturen noch unbenannt ist, mußte ein Bezeichnungsmodus gefun- den werden, um die kartierten Strukturen in den Tabellen wiederzufinden. Hierbei wurde fol- gendermaßen verfahren: Strukturen, die in der N¨ahe einer benannten Impaktstruktur (Krater, Palimpsest, oder Ringbecken) liegen, wurden auf diese jeweilige Struktur bezogen. Die Impakt- strukturen wurden mit den beiden Anfangsbuchstaben (bzw. mit dem Anfangsbuchstaben der ersten und zweiten Silbe) der benannten Struktur abgekurzt¨ und dann durchnummeriert. Ab- weichend davon kamen auch Bezeichnungen von SSI-Zielgebieten (etwa gap fill = Gf ) oder andere Benennungsformen, etwa im Fall des mutmaßlichen großen Beckens zentriert um den Antapexpunkt (Antabex B = Ab) zur Anwendung. Im Gebiet RM-5, das dem SSI-Zielgebiet G7CSGLOBAL01 in nur relativ niedriger SSI-Aufl¨osung von 6.4 km/pxl entspricht, wurden noch keine Krater benannt. Die Gruppennamen in Tabelle B.6, denen die einzelnen Impaktstrukturen zugeordnet sind, entsprechen dem Namen des jewei- ligen Quadrangles, in dem sie liegen (Einteilung und Benennung der Quadrangles siehe Abb. A.1 und Tabelle A.1 in vorangehendem Abschnitt A). In Einzelf¨allen wurden neue Namen fur¨ Krater, Palimpseste oder Ringstrukturen definiert (vergl. hierzu auch Abschnitt 5.4.1). Diese Namen wurden im letzten Quartal 2006 beim den U. -

Hi Peeps! Science! This Week, We Travel to Callisto Which Is the 2Nd

Hi Peeps! Science! This week, we travel to Callisto which is the 2nd largest moon of the Jovian System after Ganymede. In the story, this is where the history of the Jovian Realm is recorded for the Book of Worlds. Given the real landscape of Callisto, I thought I’d incorporate the surface geography into that aspect of the story. Exactly how I did that will be revealed in book 4 but in the meantime, here are some fun facts to remember: • The name Callisto, comes from Greek Mythology. • It’s almost as big as Mercury but is not a planet because it does not orbit the sun. • One orbit of Jupiter takes 16.7 days. • It moves at 18,400 miles per hour. • Callisto is composed of approximately equal amounts of rock and ice. • Callisto may have a small silicate core and possibly a subsurface ocean of liquid water. This means it may be able to harbor life. • The surface of Callisto is the oldest and most heavily cratered in the Solar System. Its surface is completely covered with impact craters. • Some are chains of craters and within each crater, there is another. Some have multi-ring structures with ridges. • It does not show any signs of plate tectonics which means no separation of mass under the surface. • There are no signs that volcanic activity ever existed. • Callisto’s rotation is tidally locked to its orbit around Jupiter, so that the same hemisphere always faces inward towards the planet. • At a small scale, the surface is varied and made up of small, sparkly frost deposits at the tips of high spots, surrounded by a low-lying, smooth blanket of dark material. -

Thedatabook.Pdf

THE DATA BOOK OF ASTRONOMY Also available from Institute of Physics Publishing The Wandering Astronomer Patrick Moore The Photographic Atlas of the Stars H. J. P. Arnold, Paul Doherty and Patrick Moore THE DATA BOOK OF ASTRONOMY P ATRICK M OORE I NSTITUTE O F P HYSICS P UBLISHING B RISTOL A ND P HILADELPHIA c IOP Publishing Ltd 2000 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Multiple copying is permitted in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency under the terms of its agreement with the Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 7503 0620 3 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data are available Publisher: Nicki Dennis Production Editor: Simon Laurenson Production Control: Sarah Plenty Cover Design: Kevin Lowry Marketing Executive: Colin Fenton Published by Institute of Physics Publishing, wholly owned by The Institute of Physics, London Institute of Physics Publishing, Dirac House, Temple Back, Bristol BS1 6BE, UK US Office: Institute of Physics Publishing, The Public Ledger Building, Suite 1035, 150 South Independence Mall West, Philadelphia, PA 19106, USA Printed in the UK by Bookcraft, Midsomer Norton, Somerset CONTENTS FOREWORD vii 1 THE SOLAR SYSTEM 1 -

N O T I C E This Document Has Been Reproduced From

N O T I C E THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED FROM MICROFICHE. ALTHOUGH IT IS RECOGNIZED THAT CERTAIN PORTIONS ARE ILLEGIBLE, IT IS BEING RELEASED IN THE INTEREST OF MAKING AVAILABLE AS MUCH INFORMATION AS POSSIBLE .A, !SAND NOTE N81-11972 COORDINATES OF FEATURE S p ASA-CR-16372u) N .ILEAN SATELLITES (RAND Corp•) CSCL 03B 111E AL Unclas HC A04/mr ;k01 G3/91 2-9157 COORDINATES OF FEATURES ON THE CALILEAN SATELLITES Merton E. Davies and Frank Y. Katayama November 1980 N-1617-JPL/NASA Prepared For The Jet Propulsion Laboratory and The National Aeronautics and Space Administration Raa`1 SANTA MONICA, CA. 90406 COORDINATES Or FEATURES ON THE GALILEAN SATELLITES Merton E. Davies and Frank Y. Katayama Submitted for publication to ,Tofu-p2aZ of Geophysical Rcseax,ch October 31, 1980 -iii- PREFACE Development of control nets for the four Galilean satellites began shortly after the two Voyager spacecraft flybys of Jupiter in 1979. A preliminary report on the progress of the control nets was published in November 1979 (R-2532-JPL/W3A). This updated report will be published in the Journal of Geophysical Reaearch. The work is supported by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the National Aeronautics and Space Admin- istration. The results are of primary interest to planetary cartogra- phers. _v_ SUMMARY Control nets of the four Galilean satellites have been established photogrLmmetrically from pictures taken by the two Voyager spacecraft during their flybys of Jupiter in 1979. Coordinates of 504 points on lo, 112 points on Europa, 1547 points on Ganymeds, and 439 points on Callisto are listed. -

9. Zusammenfassung Der Ergebnisse Und Ausblick

9. Zusammenfassung der Ergebnisse und Ausblick 9.1. Kraterh¨aufigkeitsverteilungen und Impaktchronologiemodelle 9.1.1. Form der Produktionskraterverteilungen Messungen der Kratergr¨oßen-H¨aufigkeitsverteilungen auf Callisto zeigten, dass ihre Formen kom- plexe Strukturen aufweisen, die sich wie beim Erdmond und den terrestrischen Planeten durch ein Polynom 11. Grades approximieren lassen (Neukum, 1983, 1985, 1997; Neukum et al., 1998, 2007). Fur¨ den Durchmesserbereich gr¨oßer als ≈ 5 km konnten ¨altere, auf Voyager-Daten ba- sierende Messungen best¨atigt werden (Neukum, 1985; Schmidt, 1988; Schmidt et al., 1989). Die Galileo-SSI-Daten erm¨oglichten erstmals auch Messungen von Kraterverteilungen bis herab in den Zehnermeterbereich. Wagner et al. (2004, 2006c) fassten die wesentlichen Erkenntnisse uber¨ die Krater-H¨aufigkeits- verteilungen auf Callisto uber¨ den gesamten messbaren Durchmesserbereich zusammen: 1. Die Form der Verteilungen ist fur¨ Krater uber¨ ≈ 5 km Durchmesser ¨ahnlich denen auf den terrestrischen Planeten. 2. Die Kraterdichte liegt etwa einen Faktor 3 - 4 unter der der lunaren Hochl¨ander. Mit wenigen Ausnahmen von Verteilungen im Durchmesserbereich zwischen 1 und 5 km bzw. von geologisch uberpr¨ ¨agten Einheiten liegen Produktionsverteilungen vor. Eine generelle ”S¨attigung” der Callisto-Oberfl¨ache mit Kratern (bzw. Equilibriumsverteilung), wie von Zahnle et al. (1998, 2003) diskutiert, ist nicht nachzuweisen. 3. Aus Messungen in den zwei Variet¨aten der Kraterebenen konnte keine Apex-Antapex- Asymmetrie in den H¨aufigkeiten nachgewiesen werden, die ein Indikator fur¨ vorwiegend heliozentrische Projektile w¨are (Shoemaker und Wolfe, 1982; Shoemaker et al., 1982). Da eine wenn auch sehr langsame nicht-synchrone Rotation der ¨außeren Eiskruste uber¨ ei- nem inneren Ozean vermutlich wegen der viel zu geringen Gezeitenwechselwirkung bei Callisto nahezu auszuschließen ist, sind uberwiegend¨ planetozentrische, durch Jupiter ein- gefangene Projektile die wahrscheinlichste Ursache. -

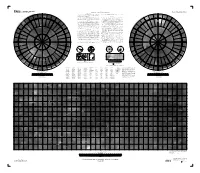

CONTROLLED PHOTOMOSAIC MAP of CALLISTO for Sale by U.S

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Prepared for the GEOLOGIC INVESTIGATIONS SERIES I–2770 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION ATLAS OF JOVIAN SATELLITES: CALLISTO 180° 0° 55° NOTES ON BASE Jc 15M CMN: Abbreviation for Jupiter, Callisto (satellite): 1:15,000,000 series, controlled mosaic –55° This sheet is one in a series of maps of the Galilean satellites of Jupiter at a nominal scale of (CM), nomenclature (N) (Greeley and Batson, 1990). 1:15,000,000. This series is based on data from the Galileo Orbiter Solid-State Imaging (SSI) cam- era and the cameras of the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. 2 REFERENCES 3 0° 10 PROJECTION 0° Lofn 30 15 ° Batson, R.M., 1987, Digital cartography of the planets—New methods, its status, and its future: 3 ° 60° Mercator and Polar Stereographic projections used for this map of Callisto are based on a sphere –60° having a radius of 2,409.3 km. The scale is 1:8,388,000 at ±56° latitude for both projections. Longi- Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing, v. 53, no. 9, p. 1211–1218. tude increases to the west in accordance with the International Astronomical Union (1971) (Seidel- Becker, T.L., Archinal, B., Colvin, T.R., Davies, M.E., Gitlin, A., Kirk, R.L., and Weller, L., 2001, mann and others, 2002). Final digital global maps of Ganymede, Europa, and Callisto, in Lunar and Planetary Science Conference XXXII: Houston, Lunar and Planetary Institute, abs. no. 2009 [CD-ROM]. Nyctimus . Hijsi CONTROL Becker, T.L., Rosanova, T., Cook, D., Davies, M.E., Colvin, T.R., Acton, C., Bachman, N., Kirk, The geometric control network was computed at the RAND Corporation using RAND’s most R.L., and Gaddis, L.R., 1999, Progress in improvement of geodetic control and production of Heimdall . -

Lunar and Planetary Science XXX 1818.Pdf

Lunar and Planetary Science XXX 1818.pdf AGES OF INDIVIDUAL CRATERS ON THE GALILEAN SATELLITES GANYMEDE AND CALLISTO. R. Wagner1, U. Wolf1, G. Neukum1, and the Galileo SSI Team. 1DLR, Institute of Planetary Exploration, Berlin, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] Introduction: Craters, palimpsests and multi-ringed used for modeling crater ages on Galilean satellite surfaces. basins are important stratigraphic markers in establishing Model I, as discussed by [3], assumes a lunar-like, prefer- sequences of geologic events by crosscutting relationships. entially asteroidal bombardment of the jovian satellites, Impact structure forms, hence the style of crustal response with a period of heavy bombardment which ended about towards impact deformation, also may have changed 3.8 billion years (b.y.) ago - forming the youngest large through geologic time. Measurements of crater distribu- multi-ring basins, such as Gilgamesh on Ganymede - and a tions mapped in these impact structures and their sur- more or less constant cratering rate since about 3.3 b.y. rounding terrain provide a valuable tool in order to estab- Cratering Model I ages are derived by solving equation (1) lish an age sequence. From the application of cratering for exposition time t (in b.y.). Coefficients A, B and C for chronology models, absolute ages for these impact struc- all three icy Galilean are given in table 1. Age uncertainties tures can be derived also. In this paper we present ages for are on the order of 0.05 b.y. for surfaces older than 3.3 b.y. impact events which created craters and impact structures but may amount to 0.5 b.y.