Guidelines for Safe Child Care Operations During COVID-19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Kinship Terminology

Fox (Mesquakie) Kinship Terminology IVES GODDARD Smithsonian Institution A. Basic Terms (Conventional List) The Fox kinship system has drawn a fair amount of attention in the ethno graphic literature (Tax 1937; Michelson 1932, 1938; Callender 1962, 1978; Lounsbury 1964). The terminology that has been discussed consists of the basic terms listed in §A, with a few minor inconsistencies and errors in some cases. Basically these are the terms given by Callender (1962:113-121), who credits the terminology given by Tax (1937:247-254) as phonemicized by CF. Hockett. Callender's terms include, however, silent corrections of Tax from Michelson (1938) or fieldwork, or both. (The abbreviations are those used in Table l.)1 Consanguines Grandparents' Generation (1) nemesoha 'my grandfather' (GrFa) (2) no hkomesa 'my grandmother' (GrMo) Parents' Generation (3) nosa 'my father' (Fa) (4) nekya 'my mother' (Mo [if Ego's female parent]) (5) nesekwisa 'my father's sister' (Pat-Aunt) (6) nes'iseha 'my mother's brother' (Mat-Unc) (7) nekiha 'my mother's sister' (Mo [if not Ego's female parent]) 'Other abbreviations used are: AI = animate intransitive; AI + O = tran- sitivized AI; Ch = child; ex. = example; incl. = inclusive; m = male; obv. = obviative; pi. = plural; prox. = proximate; sg. = singular; TA = transitive ani mate; TI-0 = objectless transitive inanimate; voc. = vocative; w = female; Wi = wife. Some citations from unpublished editions of texts by Alfred Kiyana use abbreviations: B = Buffalo; O = Owl (for these, see Goddard 1990a:340). 244 FOX -

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy with At-Risk Families

ISSUE BRIEF January 2013 Parent-Child Interaction Therapy With At-Risk Families Parent-child interaction therapy (PCIT) is a family-centered What’s Inside: treatment approach proven effective for abused and at-risk children ages 2 to 8 and their caregivers—birth parents, • What makes PCIT unique? adoptive parents, or foster or kin caregivers. During PCIT, • Key components therapists coach parents while they interact with their • Effectiveness of PCIT children, teaching caregivers strategies that will promote • Implementation in a child positive behaviors in children who have disruptive or welfare setting externalizing behavior problems. Research has shown that, as a result of PCIT, parents learn more effective parenting • Resources for further information techniques, the behavior problems of children decrease, and the quality of the parent-child relationship improves. Child Welfare Information Gateway Children’s Bureau/ACYF 1250 Maryland Avenue, SW Eighth Floor Washington, DC 20024 800.394.3366 Email: [email protected] Use your smartphone to https:\\www.childwelfare.gov access this issue brief online. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy With At-Risk Families https://www.childwelfare.gov This issue brief is intended to build a better of the model, which have been experienced understanding of the characteristics and by families along the child welfare continuum, benefits of PCIT. It was written primarily to such as at-risk families and those with help child welfare caseworkers and other confirmed reports of maltreatment or neglect, professionals who work with at-risk families are described below. make more informed decisions about when to refer parents and caregivers, along with their children, to PCIT programs. -

What Is a Child & Family Team Meeting?

What is a Child & Family Team When is a Child & Family Team Meeting Location and Time Meeting? Meeting Necessary? We believe that Child & Family Team Meetings should be conducted at a mutu- A Child & Family Team Meeting (CFT) is A child has been found to be at high risk. ally agreeable and accessible location/time a strength based meeting that brings to- A child is at risk of out of home place- that maximizes opportunities for family gether your family, natural supports, and ment. participation. Please let us know your pref- formal resources. The meeting is lead by a Prior to the removal of a child from his erences regarding the time and location of trained facilitator to ensure that all partici- home. your meeting. pants have an opportunity to be involved Prior to a placement change of a child and heard. The purpose of the meeting is already in care. You have the right to…. to address the needs of your family and to Have your rights explained to you in a Prior to a change in a child’s perma- manner which is clear build upon its strengths. The goal of the nency goal. process is to enable your child(ren) to re- When requested by a parent, social main safely at home whenever possible. Receive written information or interpre- worker, or youth. tation in your native language. When there are multiple agencies in- The purpose of the Child & volved. Read, review, and receive written infor- At other critical decision points. mation regarding your child’s record Family Team Meeting is upon request. -

Convention on the Rights of the Child

Convention on the Rights of the Child Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989 entry into force 2 September 1990, in accordance with article 49 Preamble The States Parties to the present Convention, Considering that, in accordance with the principles proclaimed in the Charter of the United Nations, recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Bearing in mind that the peoples of the United Nations have, in the Charter, reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights and in the dignity and worth of the human person, and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, Recognizing that the United Nations has, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in the International Covenants on Human Rights, proclaimed and agreed that everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth therein, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status, Recalling that, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations has proclaimed that childhood is entitled to special care and assistance, Convinced that the family, as the fundamental group of society and the natural environment for the growth and well-being of all its members and particularly children, should be afforded -

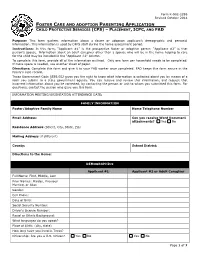

Foster Care and Adoption Parenting Application PDF Document

Form K-902-2286 Revised October 2014 FOSTER CARE AND ADOPTION PARENTING APPLICATION CHILD PROTECTIVE SERVICES (CPS) – PLACEMENT, ICPC, AND FAD Purpose: This form gathers information about a foster or adoption applicant’s demographic and personal information. This information is used by DFPS staff during the home assessment period. Instructions: In this form, “Applicant #1” is the prospective foster or adoptive parent. “Applicant #2” is that person’s spouse. Information about an adult caregiver other than a spouse who will be in the home helping to care for the child may be included in the “Applicant #2” column. To complete this form, provide all of the information outlined. Only one form per household needs to be completed. If more space is needed, use another sheet of paper. Directions: Complete this form and give it to your FAD worker once completed. FAD keeps this form secure in the family’s case record. Texas Government Code §559.002 gives you the right to know what information is collected about you by means of a form you submit to a state government agency. You can receive and review this information, and request that incorrect information about you be corrected, by contacting the person or unit to whom you submitted this form. For questions, contact the person who gave you this form. INFORMATION MEETING/ORIENTATION ATTENDANCE DATE: FAMILY INFORMATION Foster/Adoptive Family Name Home Telephone Number Email Address: Can you receive Word Document attachments? Yes No Residence Address (Street, City, State, Zip) Mailing Address (if different) County: School District: Directions to the Home: DEMOGRAPHICS Applicant #1 Applicant #2 or Adult Caregiver Full Name: First, Middle, Last Prior Names: Maiden, Previous Married, or Alias Gender: Cell Phone: Date of Birth: Social Security Number: Driver's License Number: Racial or Ethnic Background: What languages do you speak? Place of Birth: (city, state) How long have you lived in Texas? Citizenship: Are you a U.S. -

Formal Analysis of Kinship Terminologies and Its Relationship to What Constitutes Kinship (Complete Text)

MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL VOLUME 1 NO. 1 PAGE 1 OF 46 NOVEMBER 2000 FORMAL ANALYSIS OF KINSHIP TERMINOLOGIES AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO WHAT CONSTITUTES KINSHIP (COMPLETE TEXT) 1 DWIGHT W. READ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90035 [email protected] Abstract The goal of this paper is to relate formal analysis of kinship terminologies to a better understanding of who, culturally, are defined as our kin. Part I of the paper begins with a brief discussion as to why neither of the two claims: (1) kinship terminologies primarily have to do with social categories and (2) kinship terminologies are based on classification of genealogically specified relationships traced through genitor and genetrix, is adequate as a basis for a formal analysis of a kinship terminology. The social category argument is insufficient as it does not account for the logic uncovered through the formalism of rewrite rule analysis regarding the distribution of kin types over kin terms when kin terms are mapped onto a genealogical grid. Any formal account must be able to account at least for the results obtained through rewrite rule analysis. Though rewrite rule analysis has made the logic of kinship terminologies more evident, the second claim must also be rejected for both theoretical and empirical reasons. Empirically, ethnographic evidence does not provide a consistent view of how genitors and genetrixes should be defined and even the existence of culturally recognized genitors is debatable for some groups. In addition, kinship relations for many groups are reckoned through a kind of kin term calculus independent of genealogical connections. -

Child Marriage and POVERTY

Child Marriage and POVERTY Child marriage is most common in the world’s poorest countries and is often concentrated among the poorest households within those countries. It is closely linked with poverty and low levels of economic development. In families with limited resources, child marriage is often seen as a way to provide for their daughter’s future. But girls who marry young are IFAD / Anwar Hossein more likely to be poor and remain poor. CHILD MARRIAGE Is INTIMATELY shows that household economic status is a key factor in CONNEctED to PovERTY determining the timing of marriage for girls (along with edu- cation and urban-rural residence, with rural girls more likely Child marriage is highly prevalent in sub- to marry young). In fact, girls living in poor households are Saharan Africa and parts of South Asia, the approximately twice as likely to marry before 18 than girls two most impoverished regions of the world.1 living in better-off households.4 • More than half of the girls in Bangladesh, Mali, Mozam- In Côte d’Ivoire, a target country for the President’s Emer- bique and Niger are married before age 18. In these same gency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), girls in the poorest countries, more than 75 percent of people live on less than $2 a day. In Child Marriage in the Poorest and Richest Households Mali, 91 percent of the in Select Countries population lives on less 80 than $2 a day. 2 70 • Countries with low GDPs tend to have a higher 60 prevalence of child mar- riage. -

Child–Parent Psychotherapy a Trauma-Informed Treatment for Young Children and Their Caregivers

CHAPTER 29 Child–Parent Psychotherapy A Trauma-Informed Treatment for Young Children and Their Caregivers Alicia F. Lieberman Miriam Hernandez Dimmler Chandra Michiko Ghosh Ippen Child–parent psychotherapy (CPP) is a rela- tions that impair the parent–child relationship, tionship-based treatment for infants, toddlers, such as depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic and preschoolers who are experiencing mental stress; and frightening or maladaptive parent health problems or are at risk for such distur- and child behaviors, including externalizing bances due to exposure to traumatic events, problems (e.g., excessive controllingness, pu- environmental adversities, parental mental ill- nitiveness, self-endangerment and aggression) ness, maladaptive parenting practices, and/or and internalizing problems, such as emotional discordant parent–child temperamental styles. constriction and social withdrawal (Lieberman, The overarching goal of treatment is to help Ghosh Ippen, & Van Horn, 2015). parents create physical and emotional safety for the child and the family. This goal of physi- cal and psychological safety is pursued through Reality and Internalization in the therapeutic strategies designed to promote an Child–Parent Relationship age-appropriate, goal-corrected partnership between parent and child (Bowlby, 1969), in The cornerstone of CPP is Bowlby’s premise which parents become the child’s protectors and that reality matters, and that the parents’ avail- guides in striving toward three components of ability and competence as protectors from early mental health: developmentally expectable danger are key ingredients in fostering young emotional regulation, safe and rewarding rela- children’s secure attachments (Bowlby, 1969). tionships, and joyful engagement in exploration Attachment theory placed the function of chil- and learning. -

NCI Child Family Survey State Outcomes

NCI Child Family Survey State Outcomes California Report 2015-16 Data National Core Indicators™ Table of Contents What is NCI? ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 What is the NCI Child Family Survey? ............................................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 How were people selected to participate? ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Limitations of the data ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 What is contained in this report? ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Results: Demographics of the Child ....................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Child Marriage: a Mapping of Programmes and Partners in Twelve Countries in East and Southern Africa

CHILD MARRIAGE A MAPPING OF PROGRAMMES AND PARTNERS IN TWELVE COUNTRIES IN EAST AND SOUTHERN AFRICA i Acknowledgements Special thanks to Carina Hickling (international consultant) for her technical expertise, skills and dedication in completing this mapping; to Maja Hansen (Regional Programme Specialist, Adolescent and Youth, UNFPA East and Southern Africa Regional Office) and Jonna Karlsson (Child Protection Specialist, UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office) for the guidance on the design and implementation of the study; and to Maria Bakaroudis, Celine Mazars and Renata Tallarico from the UNFPA East and Southern Africa Regional Office for their review of the drafts. The final report was edited by Lois Jensen and designed by Paprika Graphics and Communications. We also wish to express our appreciation to the global and regional partners that participated as informants in the study, including the African Union Commission, Secretariat for the African Union Campaign to End Child Marriage; Girls Not Brides; Population Council; Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency – Zambia regional office; World YWCA; Commonwealth Secretariat; Rozaria Memorial Trust; Plan International; Inter-Africa Committee on Traditional Practices; Save the Children; Voluntary Service Overseas; International Planned Parenthood Federation Africa Regional Office; and the Southern African Development Community Parliamentary Forum. Special thanks to the UNFPA and UNICEF child marriage focal points in the 12 country offices in East and Southern Africa (Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, South Sudan, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe) and the governmental and non-governmental partners that provided additional details on initiatives in the region. The information contained in this report is drawn from multiple sources, including interviews and a review of materials available online and provided by organizations. -

The Global State of Evidence on Interventions to Prevent Child Marriage Sophia Chae and Thoai D

GIRL Center Research Brief No. 1 October 2017 THE GLOBAL STATE OF EVIDENCE ON INTERVENTIONS to PREVENT CHILD MARRIAGE sopHIA CHAE AND THOAI D. NGO The Girl Innovation, Research, and Learning (GIRL) Center generates, synthesizes, and translates evidence to transform the lives of adolescent girls popcouncil.org/girlcenter GIRL Center Research Briefs present new knowledge on issues of current and critical importance and recommend future directions for research, policies, and programs. “The Global State of Evidence on Interventions to Prevent Child Marriage” was made possible through the generous support of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Mark A. Walker Fellowship Program to the Girl Innovation, Research, and Learning (GIRL) Center. We are grateful to Sajeda Amin, Annabel Erulkar, and Michelle Hindin for providing valuable comments on earlier versions of this brief. Suggested citation: Chae, Sophia and Thoai D. Ngo. 2017. “The Global State of Evidence on Interventions to Prevent Child Marriage,” GIRL Center Research Brief No. 1. New York: Population Council. © 2017 The Population Council, Inc. GRowInG ReCoGnItIon of the haRmfuL effeCts of ChILd maRRIaGe has pLaCed Its eLImInatIon on the GLoBaL and natIonaL aGenda. to addRess thIs pRoBLem, we RevIewed the GLoBaL state of evIdenCe on what woRks to pRevent ChILd maRRIaGe. Our research focuses exclusively on rigorously evaluated interventions, defined as interventions evaluated as part of a randomized controlled trial (RCT), quasi-experimental study, or a natural experiment, and incorporates new results not included in previous reviews. In total, 22 interventions across 13 low- and middle-income countries met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review.