Four Thousand Years of Concepts Relating to Rabies in Animals and Humans, Its Prevention and Its Cure Arnaud Tarantola

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invented Herbal Tradition.Pdf

Journal of Ethnopharmacology 247 (2020) 112254 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Ethnopharmacology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jethpharm Inventing a herbal tradition: The complex roots of the current popularity of T Epilobium angustifolium in Eastern Europe Renata Sõukanda, Giulia Mattaliaa, Valeria Kolosovaa,b, Nataliya Stryametsa, Julia Prakofjewaa, Olga Belichenkoa, Natalia Kuznetsovaa,b, Sabrina Minuzzia, Liisi Keedusc, Baiba Prūsed, ∗ Andra Simanovad, Aleksandra Ippolitovae, Raivo Kallef,g, a Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Via Torino 155, 30172, Mestre, Venice, Italy b Institute for Linguistic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Tuchkov pereulok 9, 199004, St Petersburg, Russia c Tallinn University, Narva rd 25, 10120, Tallinn, Estonia d Institute for Environmental Solutions, "Lidlauks”, Priekuļu parish, LV-4126, Priekuļu county, Latvia e A.M. Gorky Institute of World Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 25a Povarskaya st, 121069, Moscow, Russia f Kuldvillane OÜ, Umbusi village, Põltsamaa parish, Jõgeva county, 48026, Estonia g University of Gastronomic Sciences, Piazza Vittorio Emanuele 9, 12042, Pollenzo, Bra, Cn, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Ethnopharmacological relevance: Currently various scientific and popular sources provide a wide spectrum of Epilobium angustifolium ethnopharmacological information on many plants, yet the sources of that information, as well as the in- Ancient herbals formation itself, are often not clear, potentially resulting in the erroneous use of plants among lay people or even Eastern Europe in official medicine. Our field studies in seven countries on the Eastern edge of Europe have revealed anunusual source interpretation increase in the medicinal use of Epilobium angustifolium L., especially in Estonia, where the majority of uses were Ethnopharmacology specifically related to “men's problems”. -

World Rabies Day: Making the Most of Your Event

World Rabies Day: Making the most of your event Thank you! By organizing a World Rabies Day event you are taking part in a global movement to put an end to the unnecessary suffering caused by rabies. You and people like you are what make World Rabies Day the global phenomenon that it is. This manual was created to help you plan and communicate your World Rabies Day event to different audiences. We welcome your feedback to improve this resource – email us at [email protected] with your suggestions. Contents The Basics of World Rabies Day .................................................................................................................... 3 When is World Rabies Day? ...................................................................................................................... 3 What is World Rabies Day? ....................................................................................................................... 3 What is a World Rabies Day event? .......................................................................................................... 4 Why should I register my event? .............................................................................................................. 4 Why does World Rabies Day help? ........................................................................................................... 4 Registering your event .............................................................................................................................. 4 Ideas for -

Global Strategic Plan to End Human Deaths from Dog-Mediated Rabies by 2030

UNITED AGAINST RABIES COLLABORATION Cover photo credits: © Serengeti Carnivore Disease Project / FAO and WHO / FAO Carnivore Disease Project © Serengeti Cover photo credits: First annual progress report ZERO BY 30 THE GLOBAL STRATEGIC PLAN TO END HUMAN DEATHS FROM DOG-MEDIATED RABIES BY 2030 ISBN 978-92-4-151383-8 United Against Rabies Collaboration First annual progress report: Global Strategic Plan to End Human Deaths from Dog-mediated Rabies by 2030 World Health Organization Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations World Organisation for Animal Health Global Alliance for Rabies Control Geneva, 2019 United Against Rabies Collaboration First annual progress report: Global Strategic Plan to End Human Deaths from Dog-mediated Rabies by 2030 © World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), 2019 All rights reserved. WHO, FAO and OIE encourage the reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Any proposed reproduction or dissemination for non-commercial purposes will be authorized free of charge upon request, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Any proposed reproduction or dissemination for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holders, and may incur fees. Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for non-commercial distri- bution – should be addressed to -

HUNTIA a Journal of Botanical History

HUNTIA A Journal of Botanical History VOLUME 16 NUMBER 2 2018 Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh The Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, a research division of Carnegie Mellon University, specializes in the history of botany and all aspects of plant science and serves the international scientific community through research and documentation. To this end, the Institute acquires and maintains authoritative collections of books, plant images, manuscripts, portraits and data files, and provides publications and other modes of information service. The Institute meets the reference needs of botanists, biologists, historians, conservationists, librarians, bibliographers and the public at large, especially those concerned with any aspect of the North American flora. Huntia publishes articles on all aspects of the history of botany, including exploration, art, literature, biography, iconography and bibliography. The journal is published irregularly in one or more numbers per volume of approximately 200 pages by the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation. External contributions to Huntia are welcomed. Page charges have been eliminated. All manuscripts are subject to external peer review. Before submitting manuscripts for consideration, please review the “Guidelines for Contributors” on our Web site. Direct editorial correspondence to the Editor. Send books for announcement or review to the Book Reviews and Announcements Editor. All issues are available as PDFs on our Web site. Hunt Institute Associates may elect to receive Huntia as a benefit of membership; contact the Institute for more information. Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Carnegie Mellon University 5th Floor, Hunt Library 4909 Frew Street Pittsburgh, PA 15213-3890 Telephone: 412-268-2434 Email: [email protected] Web site: http://www.huntbotanical.org Editor and layout Scarlett T. -

Dioscorides De Materia Medica Pdf

Dioscorides de materia medica pdf Continue Herbal written in Greek Discorides in the first century This article is about the book Dioscorides. For body medical knowledge, see Materia Medica. De materia medica Cover of an early printed version of De materia medica. Lyon, 1554AuthorPediaus Dioscorides Strange plants RomeSubjectMedicinal, DrugsPublication date50-70 (50-70)Pages5 volumesTextDe materia medica in Wikisource De materia medica (Latin name for Greek work Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς, Peri hul's iatrik's, both means about medical material) is a pharmacopeia of medicinal plants and medicines that can be obtained from them. The five-volume work was written between 50 and 70 CE by Pedanius Dioscorides, a Greek physician in the Roman army. It was widely read for more than 1,500 years until it supplanted the revised herbs during the Renaissance, making it one of the longest of all natural history books. The paper describes many drugs that are known to be effective, including aconite, aloe, coloxinth, colocum, genban, opium and squirt. In all, about 600 plants are covered, along with some animals and minerals, and about 1000 medicines of them. De materia medica was distributed as illustrated manuscripts, copied by hand, in Greek, Latin and Arabic throughout the media period. From the sixteenth century, the text of the Dioscopide was translated into Italian, German, Spanish and French, and in 1655 into English. It formed the basis of herbs in these languages by such people as Leonhart Fuchs, Valery Cordus, Lobelius, Rembert Dodoens, Carolus Klusius, John Gerard and William Turner. Gradually these herbs included more and more direct observations, complementing and eventually displacing the classic text. -

Prehľad Dejín Biológie, Lekárstva a Farmácie

VYSOKOŠKOLSKÁ UČEBNICA UNIVERZITA PAVLA JOZEFA ŠAFÁRIKA V KOŠICIACH PRÍRODOVEDECKÁ FAKULTA Katedra botaniky Prehľad dejín biológie, lekárstva a farmácie Martin Bačkor a Miriam Bačkorová Košice 2018 PREHĽAD DEJÍN BIOLÓGIE, LEKÁRSTVA A FARMÁCIE Vysokoškolská učebica Prírodovedeckej fakulty UPJŠ v Košiciach Autori: 2018 © prof. RNDr. Martin Bačkor, DrSc. Katedra botaniky, Prírodovedecká fakulta, UPJŠ v Košiciach 2018 © RNDr. Miriam Bačkorová, PhD. Katedra farmakognózie a botaniky, UVLF v Košiciach Recenzenti: doc. RNDr. Roman Alberty, CSc. Katedra biológie a ekológie, Fakulta prírodných vied, UMB v Banskej Bystrici doc. MVDr. Tatiana Kimáková. PhD. Ústav verejného zdravotníctva, Lekárska fakulta, UPJŠ v Košiciach Vedecký redaktor: prof. RNDr. Beňadik Šmajda, CSc. Katedra fyziológie živočíchov, Prírodovedecká fakulta, UPJŠ v Košiciach Technický editor: Mgr. Margaréta Marcinčinová Všetky práva vyhradené. Toto dielo ani jeho žiadnu časť nemožno reprodukovať, ukladať do in- formačných systémov alebo inak rozširovať bez súhlasu majiteľov práv. Za odbornú a jazykovú stránku tejto publikácie zodpovedajú autori. Rukopis neprešiel redakčnou ani jazykovou úpravou Tento text vznikol aj vďaka materiálnej pomoci z projektu KEGA 012UPJŠ-4/2016. Vydavateľ: Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika v Košiciach Dostupné od: 22. 10. 2018 ISBN 978-80-8152-650-3 OBSAH PREDHOVOR ................................................. 5 1 STAROVEK ................................................ 6 1.1 Zrod civilizácie ........................................................8 -

Chlorhexidine Vs. Herbal Mouth Rinses

DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/16578.7815 Original Article The Mouthwash War - Chlorhexidine vs. Herbal Mouth Dentistry Section Rinses: A Meta-Analysis SUNAYANA MANIPAL1, SAJJID HUSSAIN2, UMESH WADGAVE3, PRABU DURAISWAMY4, K. RAVI5 ABSTRACT with Boolean operators (chlorhexidine, herbal, mouth wash, Introduction: Mouthwashes are often prescribed in dentistry randomized control trials). The fixed effects model was used for prevention and treatment of several oral conditions. In the for analysis. recent times the use of naturally occurring products what is Results: This meta-analysis brings to light, the fact that a wide otherwise known as grandmothers remedy are used on a large range of newer herbal products are now available. As with scale. This has now called for a newer age of mouth washes but a plethora of herbal mouthwashes available it is the need of is the new age mouth washes at par with the gold standard or the hour to validate their potential use and recommendation. even better than them this study investigates. This study found that only two studies favor the use of herbal Aim: The aim of the present study was to compare the effect products and four studies favor the use of chlorhexidine, of the of two broad categories of mouth washes namely chlorhexidine 11 studies that were analyzed. and herbal mouth washes. Conclusion: More studies are required under well controlled Materials and Methods: Eleven randomized control studies circumstances to prove that herbal products can equate or were pooled in for the meta-analysis. The search was done replace the ‘gold standard’ chlorhexidine. Herbal products are from the Pub Med Central listed studies with the use keywords heterogeneous in nature, their use should be advised only with more scientific proof. -

The Derivation of the Name Datisca (Datiscaceae)

Holmes, W.C. and H.J. Blizzard. 2010. The derivation of the name Datisca (Datiscaceae). Phytoneuron 2010-6: 1–2. (10 March) THE DERIVATION OF THE NAME DATISCA (DATISCACEAE) WALTER C. H OLMES AND HEATHER J. B LIZZARD Department of Biology Baylor University Waco, Texas 76798-7388 U.S.A. [email protected] ABSTRACT The name Datisca is attributed to Dioscorides in de Materia Medica , where it was cited as a Roman common name for species of Catananche (Asteraceae). Linnaeus apparently appropriated the name from Dioscorides but used it for species of a different genus and family. The derivation of the original name remains unknown. KEY WORDS : Datisca , Datiscaceae, Dioscorides, de Materia Medica . The Datiscaceae, as it will be treated in the Flora of North America, consists of a single genus of perennial herbs, Datisca , composed of two species. These are D. cannabina L. of southwest Asia from the eastern Mediterranean to the Himalayas and D. glomerata (C. Presl) Baillon of California, extreme western Nevada (near Lake Tahoe) of the southwest United States, and Baja California Norte, Mexico. Interest in the derivation of the name Datisca originated with the preparation of a treatment of Datisca glomerata for the Flora of North America North of Mexico project. The etymology of generic names is a required entry in the generic descriptions. The present manuscript is intended to supplement the brief statement on the derivation that will be presented there. Few references were found on this topic, possibly a reflection of the small size and lack of economic importance of the family. Stone (1993), in a treatment of Datisca glomerata for The Jepson Manual , merely stated “derivation unknown.” In a treatment of Datisca cannabina L. -

Vipera Ammodytes, “Sand Viper” – Origin of Its Name, and a Sand Habitat in Greece

Vipera ammodytes, “Sand Viper” – origin of its name, and a sand habitat in Greece Henrik Bringsøe Irisvej 8 DK-4600 Køge Denmark [email protected] Photos by the author Close-up view of Vipera ammodytes from Achaia Feneos. INTRODUCTION Greece has a rich viperid representation of As a guidance to habitat preference and other five species (JOGER & STÜMPEL, 2005). How- natural historical aspects of V. ammodytes, ever, four of them have small and localised my field observations on that species on the Greek distributions and are considered rare Peloponnese from April 2008 are provided. in Greece: Vipera berus in the northern Of particular relevance is one truly sandy mountains of the mainland, Vipera graeca in habitat in a coastal region with a rich popula- northern and central upland regions of the tion. mainland, Macrovipera schweizeri in the Mi- I will also explore the nomenclatural facets of los Archipelago (Western Cyclades), and V. ammodytes in a historical context as the Montivipera xanthina on the Eastern Aegean record behind well-established scientific islands and in coastal Thrace. names often dates much further back in time The fifth species, Vipera ammodytes, is ubi- than what the formal authorship of the bino- quitous (BRINGSØE, 1986; HECKES et al., mial names reveal. The oldest recognised bi- 2005; TRAPP, 2007) and basically forms a vi- nomial names date of course from 1758, i.e. perid landmark of Greece. Its popular name Linné’s Systema naturae (10th edition) which is either Sand Viper or Nose-horned Viper was, regrettably, very superficial in terms of (ARNOLD, 2002; STUMPEL-RIENKS, 1992). -

Vermin, Victims Disease

Vermin, Victims and Disease British Debates over Bovine Tuberculosis and Badgers ANGELA CASSIDY Vermin, Victims and Disease Angela Cassidy Vermin, Victims and Disease British Debates over Bovine Tuberculosis and Badgers Angela Cassidy Centre for Rural Policy Research (CRPR) University of Exeter Exeter, UK ISBN 978-3-030-19185-6 ISBN 978-3-030-19186-3 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19186-3 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019 This book is an open access under a CC BY 4.0 license via link.springer.com. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

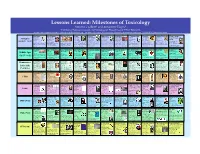

Lessons Learned: Milestones of Toxicology! Steven G

Lessons Learned: Milestones of Toxicology! Steven G. Gilbert1 and Antoinette Hayes2! 1Institute of Neurotoxicology and Neurological Disorders and 2Pfizer Research,! Contact information: Steven G. Gilbert at [email protected] – For more information, its interactive (clickable) at www.toxipedia.org – © 2006-2010 Steven G. Gilbert! Shen Nung Ebers Papyrus Gula 1400 BCE Homer Socrates Hippocrates Mithridates VI L. Cornelius Sulla Cleopatra Pedanius Dioscorides Mount Vesuvius 2696 BCE 1500 BCE 850 BCE (470-399 BCE) (460-377 BCE) (131-63 BCE) 82 BCE (69-30 BCE) (40-90 CE) Erupted August 24th Antiquity The Father of Egyptian records Wrote of the Charged with Greek physician, Tested antidotes Lex Cornelia de Experimented Greek 79 CE Chinese contains 110 use of arrows religious heresy observational to poisons on sicariis et with strychnine pharmacologist City of Pompeii & 3000 BCE – 90 CE Sumerian texts refer to a medicine, noted pages on anatomy poisoned with venom in the and corrupting the morals approach to human disease himself and used prisoners veneficis – law and other poisons on and Physician,wrote De Herculaneum and physiology, toxicology, female deity, Gula. This for tasting 365 herbs and epic tale of The Odyssey of local youth. Death by and treatment, founder of as guinea pigs. Created against poisoning people or prisoners and poor. Materia Medica basis for destroyed and buried spells, and treatment, mythological figure was Hemlock - active chemical modern medicine, named mixtures of substances said to have died of a toxic and The Iliad. From Greek prisoners; could not buy, Committed suicide with the modern pharmacopeia. by ash. Pliny the Elder recorded on papyrus. -

Art As Science: Scientific Illustration, 1490–1670 in Drawing, Woodcut and Copper Plate Cynthia M

Art as science: scientific illustration, 1490–1670 in drawing, woodcut and copper plate Cynthia M. Pyle Observation, depiction and description are active forces in the doing of science. Advances in observation and analysis come with advances in techniques of description and communication. In this article, these questions are related to the work of Leonardo da Vinci, 16th-century naturalists and artists like Conrad Gessner and Teodoro Ghisi, and 17th-century micrographers like Robert Hooke. So much of our thought begins with the senses. Before we forced to observe more closely so that he or she may accu- can postulate rational formulations of ideas, we actually rately depict the object of study on paper and thence com- feel them – intuit them. Artists operate at and play with municate it to other minds. The artist’s understanding is this intuitive stage. They seek to communicate their under- required for the depiction and, in a feedback mechanism, standings nonverbally, in ink, paint, clay, stone or film, or this understanding is enhanced by the act of depicting. poetically in words that remain on the intuitive level, The artist enters into the object of study on a deeper level mediating between feeling and thought. Reasoned ex- than any external study, minus subjective participation, plication involves a logical formulation of ideas for pres- would allow. entation to the rational faculties of other minds trained to Techniques (technai or artes as they were called in be literate and articulate. antiquity and the Middle Ages) for the execution of draw- Science (including scholarship) today or in the past ings were needed to depict nature accurately.