Islamic State’ in Afghanistan: What Threat Does It Hold?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES and the LANGUAGE of POLITICS in LATE COLONIAL BENGAL(L921-194?); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT and REACTION

MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE LANGUAGE OF POLITICS IN LATE COLONIAL BENGAL(l921-194?); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT AND REACTION THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL BY KOUSHIKIDASGUPTA ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF GOUR BANGA MALDA UPERVISOR PROFESSOR I. SARKAR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL RAJA RAMMOHANPUR, DARJEELING WEST BENGAL 2011 IK 35 229^ I ^ pro 'J"^') 2?557i UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL Raja Rammohunpur P.O. North Bengal University Dist. Darjeeling - 734013 West Bengal (India) • Phone : 0353 - 2776351 Ref. No Date y.hU. CERTIFICATE OF GUIDE AND SUPERVISOR Certified that the Ph.D. thesis prepared by Koushiki Dasgupta on Minor Political Parties and the Language of Politics in Late Colonial Bengal ^921-194'^ J Attitude, Adjustment and Reaction embodies the result of her original study and investigation under my supervision. To the best of my knowledge and belief, this study is the first of its kind and is in no way a reproduction of any other research work. Dr.LSarkar ^''^ Professor of History Department of History University of North Bengal Darje^ingy^A^iCst^^a^r Department of History University nfVi,rth Bengal Darjeeliny l\V Bj DECLARATION I do hereby declare that the thesis entitled MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE LANGUAGE OF POLITICS IN LATE COLONIAL BENGAL (l921- 1947); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT AND REACTION being submitted to the University of North Bengal in partial fulfillment for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in History is an original piece of research work done by me and has not been published or submitted elsewhere for any other degree in full or part of it. -

January-March 2008 Content.Pmd

JANUARY - MARCH 2008 Vol. 24 No. 1 CONTENTS EDITORIAL * Publication audit, handling publication misconduct and need for 1 education of authors: A Pakistani perspective Shaukat Ali Jawaid ORIGINAL ARTICLE * Shoulder Instability: The Role of MR Arthrography in Diagnosing Anteroinferior 6 Labroligamentous Lesions: Our experience at King Hussein Medical Center, Jordan Asem Al Hiari * Stress and depression among medical students: A cross sectional study at 12 a medical college in Saudi Arabia Hamza Mohammad Abdulghani * Comparative studies on antisickling properties of thiocyanate, 18 tellurite and hydroxyurea Oyewole OI, Malomo SO, Adebayo JO * Genotyping of thalassemia in microcytic hypochromic anemia patients 23 from Southwest Region of Iran Fakhar Rahim * Relationship between the serologic status of Helicobacter Pylori with 29 the presence of unstable angina Seyed Mohammad Alavi, Seyed Mohammad Hasan Adel, Alireza Rajabzadeh * Congenital malformations among live births at Arvand Hospital, 33 Ahwaz, Iran - A prospective study Ahmadzadeh Ali, Safikhani Zahad, Abdulahi Masoumeh, Ahmadzadeh Azar * Adenomyosis uteri in infertile women: Experience in a Tropical 38 Community Teaching Hospital Adebiyi Gbadebo Adesiyun, Modupeola Omotara Samaila, Abimbola Kolawole * Common signs and symptoms in hypothyroidism in central part of Iran 44 Ali Jabbari, Sima Besharat, Nasrin Razavianzadeh, Mansour Moetabar * The statistical analysis of application of teeth in forensic odontology center, 48 Tehran, Iran, 1980-2000 Amir Deebaei, Hadi Fathi Moghaddam, Parivash Delkhosh * Clinical presentation of late haemorrhagic disease of Newborn 52 Rehana Majeed, Yasmeen Memon, Farrukh Majeed * Evaluation of inhibitory effects of Iranian propolis against filamentous bacteria 56 Saeed Eshraghi, Shirin Valafar * Electroencephalogram findings in Saudi children with delayed language development 61 Taha Sadig Ahmed, A. -

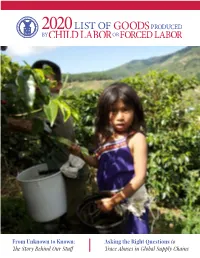

2020 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor Or Forced Labor

From Unknown to Known: Asking the Right Questions to The Story Behind Our Stuff Trace Abuses in Global Supply Chains DOWNLOAD ILAB’S COMPLY CHAIN AND APPS TODAY! Explore the key elements Discover of social best practice COMPLY CHAIN compliance 8 guidance Reduce child labor and forced systems 3 labor in global supply chains! 7 4 NEW! Explore more than 50 real 6 Assess risks Learn from world examples of best practices! 5 and impacts innovative in supply chains NEW! Discover topics like company responsible recruitment and examples worker voice! NEW! Learn to improve engagement with stakeholders on issues of social compliance! ¡Disponible en español! Disponible en français! Check Browse goods countries' produced with efforts to child labor or eliminate forced labor 1,000+ pages of research in child labor the palm of your hand! NEW! Examine child labor data on 131 countries! Review Find child NEW! Check out the Mexico laws and labor data country profile for the first time! ratifications NEW! Uncover details on 25 additions and 1 removal for the List of Goods! How to Access Our Reports We’ve got you covered! Access our reports in the way that works best for you. On Your Computer All three of the U.S. Department of Labor’s (USDOL) flagship reports on international child labor and forced labor are available on the USDOL website in HTML and PDF formats at https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor. These reports include Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor, as required by the Trade and Development Act of 2000; List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, as required by the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2005; and List of Products Produced by Forced or Indentured Child Labor, as required by Executive Order 13126. -

Situation Analysis Union Council Bandhi, District Nawabshah

NRSP Situation Analysis of U n i o n C o u n c i l B a n d h i Taluka Daur District Nawabshah October 2009 Monitoring Evaluation & Research Section National Rural Support Programme Situation Analysis of U n i o n C o u n c i l B a n d h i Taluka Daurr, District Nawabshah October 2009 Monitoring Evaluation & Research Section National Rural Support Programme ii Table of Contents Background ..............................................................................................................2 Objectives ................................................................................................................2 Methodology .............................................................................................................2 Summary of Socio-Economic Findings ..............................................................3 Introduction to the Area ............................................................................................3 Demography .............................................................................................................4 Agriculture ................................................................................................................4 Farming and Landholding Pattern ............................................................................4 Livestock ..................................................................................................................5 Education & Health ..................................................................................................5 -

Primo.Qxd (Page 1)

SATURDAY, JANUARY 4, 2014 (PAGE 6) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU GOVERNMENT OF JAMMU AND KASHMIR, 221083134 ANAMUL MAQBOOL MOHD MAQBOOL BHAT 201007298 JAVAID AHMAD PANDIT ABDUL KHALIK PANDIT 208051919 NEYAZ ALI HAJI FIDA HUSSAIN 221079082 TAHIR IQBAL NAJAR MOHD IQBAL NAJAR 207043863 YOGESHWAR SAINI MAHESH CHAND SAINI ASSISTANT 207041304 ASHWANI SHARMA TIRATH RAM SHARMA 221083356 TANVEER AHMAD MIR MOHD YOUSUF MIR JKSSB - Written Test held on 21-09-2013 for the post of - ASSISTANT 208051934 FAYAZ AHMAD GHULAM NABI 221079250 ZUBAIR FAROOQ BISATI FAROOQ AHMAD BISATI 207043939 FARYAD ALI CHOUDHARY SARAJ DIN CHOUDHARY Shortlisted Candidates List For Item Number : 262 (03 of 2012) 207041846 ANKUSH SHARMA NAND KUMAR SHARMA SERVICES SELECTION BOARD, 221083565 UMMER RASHIED AB RASHIED DAR STOREKEEPER-CUM-CLERK 208051957 MANSOOR HUSSAIN MOHD ABBAS 221079345 ABDUL SHAKOOR MOHD SULTAN LONE 207043950 MADHVI PLATHIA NANDILAL 203013112 ZAHOOR AHMAD KHAN GH MOHMAD KHAN 207041971 ANURAG SHARMA RAKESH KUMAR SHARMA JKSSB - Written Test held on 21-09-2013 for the post of - ASSTT. HAND- Shortlisted Candidates List For Item Number : 135 (03 of 2012) 208052005 MOHD BAQIR MOHD SOLEH JKSSB - Written Test held on 21-09-2013 for the post of - ASSISTANT 207043995 KANNU MANGOTRA SITA RAM SHARMA 203013163 ALIYA MANZOOR MANZOOR AHMED SHEIKH 207042012 MANSOOR AHAMMED MOHAMMED ASHRAF SHEIKH Sehkari Bhawan Panama Chowk Jammu. ICRAFTS TRAINING OFFICER 201007362 IMRAN AFAQ MOHD AFAQ 208052030 SHABINA NAZ GHULAM MOHI UD DIN STOREKEEPER-CUM-CLERK 207044127 ASHWANI KUMAR KUNJ LAL 203013212 -

Modernity, Locality and the Performance of Emotion in Sufi Cults

EMBODYING CHARISMA Emerging often suddenly and unpredictably, living Sufi saints practising in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are today shaping and reshaping a sacred landscape. By extending new Sufi brotherhoods and focused regional cults, they embody a lived sacred reality. This collection of essays from many of the subject’s leading researchers argues that the power of Sufi ritual derives not from beliefs as a set of abstracted ideas but rather from rituals as transformative and embodied aesthetic practices and ritual processes, Sufi cults reconstitute the sacred as a concrete emotional and as a dissenting tradition, they embody politically potent postcolonial counternarrative. The book therefore challenges previous opposites, up until now used as a tool for analysis, such as magic versus religion, ritual versus mystical belief, body versus mind and syncretic practice versus Islamic orthodoxy, by highlighting the connections between Sufi cosmologies, ethical ideas and bodily ritual practices. With its wide-ranging historical analysis as well as its contemporary research, this collection of case studies is an essential addition to courses on ritual and religion in sociology, anthropology and Islamic or South Asian studies. Its ethnographically rich and vividly written narratives reveal the important contributions that the analysis of Sufism can make to a wider theory of religious movements and charismatic ritual in the context of late twentieth-century modernity and postcoloniality. Pnina Werbner is Reader in Social Anthropology at Keele University. She has published on Sufism as a transnational cult and has a growing reputation among Islamic scholars for her work on the political imaginaries of British Islam. Helene Basu teaches Social Anthropology at the Institut für Ethnologie in Berlin. -

2020–21 Commencement Program

Commencement UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BOULDER MAY 6, 2021 One Hundred Forty-Fifth Year of the University NORLIN CHARGE TO THE GRADUATES The first commencement at the University of Colorado was held for six graduates on June 8, 1882, in the chapel of Old Main. It was not until 40 years later, on September 4, 1922, that the first summer commencement was held. Since the first commencement in 1882, the University of Colorado Boulder has awarded more than 350,000 degrees. The traditional Norlin Charge to the graduates was first read by President George Norlin to the June 1935 graduating class. You are now certified to the world at large as alumni of the university. She is your kindly mother and you her cherished sons and daughters. This exercise denotes not your severance from her, but your union with her. Commencement does not mean, as many wrongly think, the breaking of ties and the beginning of life apart. Rather it marks your initiation in the fullest sense into the fellowship of the university, as bearers of her torch, as centers of her influence, as promoters of her spirit. The university is not the campus, not the buildings on campus, not the faculties, not the students of any one time—not one of these or all of them. The university consists of all who come into and go forth from her halls, who are touched by her influence, and who carry on her spirit. Wherever you go, the university goes with you. Wherever you are at work, there is the university at work. -

Appellate Jurisdiction

Appellate Jurisdiction Daily Supplementary List Of Cases For Hearing On Monday, 22nd of March, 2021 CONTENT SL COURT PAGE BENCHES TIME NO. ROOM NO. NO. HON'BLE CHIEF JUSTICE THOTTATHIL B. 1 On 22-03-2021 1 RADHAKRISHNAN 1 DB - I At 10:30 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ANIRUDDHA ROY HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 37 On 22-03-2021 2 31 HON'BLE JUSTICE MD. NIZAMUDDIN DB - III At 10:30 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 22-03-2021 3 32 HON'BLE JUSTICE MD. NIZAMUDDIN DB - III At 10:30 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 28 On 22-03-2021 4 39 HON'BLE JUSTICE TIRTHANKAR GHOSH DB - IV At 10:30 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 22-03-2021 5 79 HON'BLE JUSTICE SAUGATA BHATTACHARYYA DB-V At 10:30 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 11 On 22-03-2021 6 88 HON'BLE JUSTICE HIRANMAY BHATTACHARYYA DB - VI At 10:30 AM 5 2 -03-2021 7 HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY For 4 93 SB At 02:30 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 4 On 22-03-2021 8 98 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUVRA GHOSH DB - VIII At 10:30 AM 9 On 22-03-2021 9 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHIVAKANT PRASAD 109 SB - II At 10:30 AM 13 On 22-03-2021 10 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 115 SB - III At 10:30 AM 26 On 22-03-2021 11 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHEKHAR B. SARAF 135 SB - VI At 10:30 AM 15 On 22-03-2021 12 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJARSHI BHARADWAJ 144 SB - VII At 10:30 AM 19 On 22-03-2021 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHAMPA SARKAR 167 SB - VIII At 10:30 AM 10 On 22-03-2021 14 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAVI KRISHAN KAPUR 182 SB - IX At 10:30 AM 23 On 22-03-2021 15 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM MUKHERJEE 190 SB - X At 10:30 AM 18 On 22-03-2021 16 HON'BLE JUSTICE BISWAJIT BASU 203 SB - XI At 10:30 AM 24 On 22-03-2021 17 HON'BLE JUSTICE AMRITA SINHA 211 SB - XII At 10:30 AM SL NO. -

From the Islamic State to the Messiah's Global Government: Structures of the Final World Order According to Contemporary Sunni and Shiíte Discourses

From the Islamic State to the Messiah's Global Government: Structures of the Final World Order According to Contemporary Sunni and Shiíte Discourses The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Khadem, Babak (Ali) Rod. 2017. From the Islamic State to the Messiah's Global Government: Structures of the Final World Order According to Contemporary Sunni and Shiíte Discourses. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42061520 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA FROM THE ISLAMIC STATE TO THE MESSIAH’S GLOBAL GOVERNMENT: STRUCTURES OF THE FINAL WORLD ORDER ACCORDING TO CONTEMPORARY SUNNĪ AND SHĪ’ITE DISCOURSES A dissertation presented by Babak (Ali) Rod Khadem to The Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations Harvard University Cambridge Massachusetts October, 2016 © 2016 Babak (Ali) Rod Khadem All rights reserved. Advisors: Baber Johansen and David Cook Babak (Ali) Rod Khadem From the Islamic State to the Messiah’s Global Government: Structures of the Final World Order According to Contemporary Sunnī and Shī’ite Discourses Abstract This dissertation exposes a genre of Islamic thought that has remained unstudied in academic scholarship: Islamic conceptions of “final world order.” At the intersection of political and apocalyptic thought, “final world order” refers to the theories that Islamic movements posit regarding the future global government to be established during the final chapter of history. -

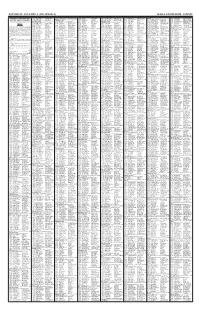

Afghanistan INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:01/02/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Afghanistan INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: ABBASIN 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: --/--/1969. POB: Sheykhan village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan a.k.a: MAHSUD, Abdul Aziz Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):AFG0121 (UN Ref): TAi.155 (Further Identifiying Information):Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we- work/Notices/View-UN-Notices-Individuals click here. Listed on: 21/10/2011 Last Updated: 01/02/2021 Group ID: 12156. 2. Name 6: ABDUL AHAD 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Mr DOB: --/--/1972. POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Nationality: Afghan National Identification no: 44323 (Afghan) (tazkira) Position: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):AFG0094 (UN Ref): TAi.121 (Further Identifiying Information): Belongs to Hotak tribe. Review pursuant to Security Council resolution 1822 (2008) was concluded on 29 Jul. 2010. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/ Notices/View-UN-Notices-Individuals click here. Listed on: 23/02/2001 Last Updated: 01/02/2021 Group ID: 7055. -

Design, Development, and Evaluation of Meso-Scale Robotic System for Deep Intracranial Tumor Removal

DESIGN, DEVELOPMENT, AND EVALUATION OF MESO-SCALE ROBOTIC SYSTEM FOR DEEP INTRACRANIAL TUMOR REMOVAL A Dissertation Presented to The Academic Faculty By Shing Shin Cheng In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Robotics Georgia Institute of Technology August 2018 Copyright c Shing Shin Cheng 2018 DESIGN, DEVELOPMENT, AND EVALUATION OF MESO-SCALE ROBOTIC SYSTEM FOR DEEP INTRACRANIAL TUMOR REMOVAL Approved by: Dr. Jaydev P. Desai Wallace H. Coulter Department of Dr. Jonathan Rogers Biomedical Engineering George W. Woodruff School of Georgia Institute of Technology Mechanical Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Jun Ueda George W. Woodruff School of Dr. John N. Oshinski Mechanical Engineering Wallace H. Coulter Department of Georgia Institute of Technology Biomedical Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Frank L. Hammond III Wallace H. Coulter Department of Date Approved: June 12, 2018 Biomedical Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my PhD advisor, Professor Jaydev P. Desai, for giving me the opportunity and believing in me who came to the lab without any Master’s experience, giving me the financial support for a technically challenging and socially meaningful project, providing me advice, feedback, and encouragement, being available every time I need more attention and guidance, and finally providing strong sup- port for my future career pursuit. He has given me opportunities after opportunities and I could not say enough thank you. I would like to thank everyone at University of Maryland School of Medicine, includ- ing Dr. Rao Gullapalli, Steve Roys, Dr. Mahamadou Diakite, Dr. -

Politics and Islamic Revivalism in Bangladesh : the Role of the State and Non‑State/Non‑Political Actors

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Politics and Islamic revivalism in Bangladesh : the role of the state and non‑state/non‑political actors Md Nazrul Islam; Md Saidul Islam 2018 Md Nazrul Islam & Md Saidul Islam (2018). Politics and Islamic revivalism in Bangladesh : the role of the state and non‑state/non‑political actors. Politics, Religion & Ideology, 19(3), 326‑353. doi:10.1080/21567689.2018.1493382 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/90313 https://doi.org/10.1080/21567689.2018.1493382 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Politics, Religion & Ideology on 5 July 2018, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/21567689.2018.1493382 Downloaded on 02 Oct 2021 06:51:55 SGT Politics and Islamic Revivalism in Bangladesh: The Role of the State and Non-State/Non- Political Actors Md. Nazrul Islam Professor Department of Political Studies Shahjalal University of Science and Technology Sylhet—3114, Bangladesh E-mail: [email protected] Md. Saidul Islam [corresponding author] Associate Professor Division of Sociology Nanyang Technological University Singapore 637332 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Bangladesh is an overwhelmingly Muslim majority country in South Asia. Islam is quite predominant in its political, social and cultural landscapes. While most classical and the contemporary sociologists predicted that religion would gradually fade in importance and cease to be significant with the advent of the industrial society, Bangladesh has witnessed a powerful reemergence of the religious forces in its society. In the recent years, the country has drawn enormous attention from the scholars and experts both locally and globally particularly with regard to its Islamic revivalism.