The Cimbalo Cromatico and Other Italian Keyboard Instruments With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View PDF Editionarrow Forward

THE DIAPASON FEBRUARY 2021 Quimby Pipe Organs, Inc. 50th Anniversary Cover feature on pages 18–20 PHILLIP TRUCKENBROD CONCERT ARTISTS ADAM J. BRAKEL THE CHENAULT DUO PETER RICHARD CONTE LYNNE DAVIS ISABELLE DEMERS CLIVE DRISKILL-SMITH DUO MUSART BARCELONA JEREMY FILSELL MICHAEL HEY HEY & LIBERIS DUO CHRISTOPHER HOULIHAN DAVID HURD MARTIN JEAN BÁLINT KAROSI JEAN-WILLY KUNZ HUW LEWIS RENÉE ANNE LOUPRETTE ROBERT MCCORMICK JACK MITCHENER BRUCE NESWICK ORGANIZED RHYTHM RAÚL PRIETO RAM°REZ JEAN-BAPTISTE ROBIN BENJAMIN SHEEN HERNDON SPILLMAN JOSHUA STAFFORD CAROLE TERRY JOHANN VEXO W͘K͘ŽdžϰϯϮ ĞĂƌďŽƌŶ,ĞŝŐŚƚƐ͕D/ϰဒϭϮϳ ǁǁǁ͘ĐŽŶĐĞƌƚĂƌƟƐƚƐ͘ĐŽŵ ĞŵĂŝůΛĐŽŶĐĞƌƚĂƌƟƐƚƐ͘ĐŽŵ ဒϲϬͲϱϲϬͲϳဒϬϬ ŚĂƌůĞƐDŝůůĞƌ͕WƌĞƐŝĚĞŶƚ WŚŝůůŝƉdƌƵĐŬĞŶďƌŽĚ͕&ŽƵŶĚĞƌ BRADLEY HUNTER WELCH SEBASTIAN HEINDL INSPIRATIONS ENSEMBLE ϮϬϭဓ>ÊĦóÊÊ'ÙÄÝ /ÄãÙÄã®ÊĽKÙ¦Ä ÊÃÖã®ã®ÊÄt®ÄÄÙ THE DIAPASON Editor’s Notebook Scranton Gillette Communications One Hundred Twelfth Year: No. 2, 20 Under 30 Whole No. 1335 We thank the many people who submitted nominations for FEBRUARY 2021 our 20 Under 30 Class of 2021. Nominations closed on Feb- Established in 1909 ruary 1. We will reveal our awardees in the May issue, with Stephen Schnurr ISSN 0012-2378 biographical information and photographs! 847/954-7989; [email protected] www.TheDiapason.com An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, A gift subscription is always appropriate. the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music Remember, a gift subscription of The Diapason for a In this issue friend, colleague, or student is a gift that is remembered each Gunther Göttsche surveys organs and organbuilding in the CONTENTS month. (And our student subscription rate cannot be beat at Holy Land. There are approximately sixty pipe organs in this FEATURES $20/year!) Subscriptions can be ordered by calling our sub- region of the world. -

Commuted Waveguide Synthesis of the Clavichord

Vesa Va¨lima¨ki,* Mikael Laurson,† Commuted Waveguide and Cumhur Erkut* *Laboratory of Acoustics and Audio Synthesis of the Signal Processing Helsinki University of Technology Clavichord P.O. Box 3000 FIN-02015 HUT Espoo, Finland {Vesa.Valimaki, Cumhur.Erkut}@hut.fi †Centre for Music and Technology Sibelius Academy P.O. Box 86 Helsinki, Finland Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/comj/article-pdf/27/1/71/1853827/01489260360613353.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 laurson@siba.fi The clavichord is one of the oldest keyboard instru- instrument is an Anthony Sidey clavichord manu- ments, and it is still often used in performances factured by Heugel in Paris, France, in 1988. This and recordings of Renaissance and Baroque music. clavichord is an unfretted one, so any combination The sound of the instrument is pleasant and ex- of notes can be played. The range of a clavichord is pressive but quiet. Consequently, the instrument anywhere from three octaves to over five octaves. can only be used in intimate performances for Our clavichord has 51 keys ranging from C2 to D6. small audiences. This is the main reason why the The instrument was tuned about a whole tone clavichord was replaced by the harpsichord and fi- lower than the standard modern tuning Hz): the nominal frequency of A4 is 395 440 ס nally by the modern piano, both of which produce (A4 a considerably louder output. Attempts have been Hz. The Werkmeister tuning system was used. made to amplify the sound of the clavichord using For each key of the clavichord, a pair of strings is a piezoelectric pickup (Burhans 1973). -

About the RPT Exams

About the RPT exams... Tuning Exam Registered Piano Technicians are This exam compares your tuning to a “master professionals who have committed themselves tuning” done by a team of examiners on the to the continual pursuit of excellence, both same piano you will tune. Electronic Tuning in technical service and ethical conduct. Aids are used to measure the master tuning Want to take The Piano Technicians Guild grants the and to measure your tuning for comparison. Registered Piano Technician (RPT) credential In Part 1 you aurally tune the middle two after a series of rigorous examinations that octaves, using a non-visual source for A440. the RPT test skill in piano tuning, regulation and In Part 2 you tune the remaining octaves by repair. Those capable of performing these any method you choose, including the use of tasks up to a recognized worldwide standard Electronic Tuning Aids. This exam takes about exams? receive the RPT credential. 4 hours. No organization has done more to upgrade the profession of the piano technician than Find an Examiner PTG. The work done by PTG members in Check with your local chapter president or developing the RPT Exams has been a major examination committee chair first to see if contribution to the advancement of higher there are local opportunities. Exam sites Prepare. include local chapters, Area Examination standards in the field. The written, tuning Boards, regional conferences and the Annual and technical exams are available exclusively PTG Convention & Technical Institute. You to PTG members in good standing. can also find contact information for chapter Practice. -

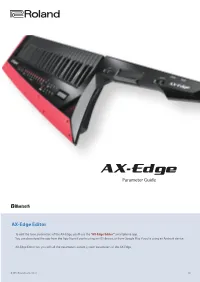

Roland AX-Edge Parameter Guide

Parameter Guide AX-Edge Editor To edit the tone parameters of the AX-Edge, you’ll use the “AX-Edge Editor” smartphone app. You can download the app from the App Store if you’re using an iOS device, or from Google Play if you’re using an Android device. AX-Edge Editor lets you edit all the parameters except system parameters of the AX-Edge. © 2018 Roland Corporation 02 List of Shortcut Keys “[A]+[B]” indicates the operation of “holding down the [A] button and pressing the [B] button.” Shortcut Explanation To change the value rapidly, hold down one of the Value [-] + [+] buttons and press the other button. In the top screen, jumps between program categories. [SHIFT] In a parameter edit screen, changes the value in steps + Value [-] [+] of 10. [SHIFT] Jumps to the Arpeggio Edit screen. + ARPEGGIO [ON] [SHIFT] Raises or lowers the notes of the keyboard in semitone + Octave [-] [+] units. [SHIFT] Shows the Battery Info screen. + Favorite [Bank] Jumps between parameter categories (such as [SHIFT] + [ ] [ ] K J COMMON or SWITCH). When entering a name Shortcut Explanation [SHIFT] Cycles between lowercase characters, uppercase + Value [-] [+] characters, and numerals. 2 Contents List of Shortcut Keys .............................. 2 Tone Parameters ................................... 19 COMMON (Overall Settings) ............................. 19 How the AX-Edge Is Organized................ 5 SWITCH .............................................. 20 : Overview of the AX-Edge......................... 5 MFX ................................................. -

Italian Harpsichord-Building in the 16Th and 17Th Centuries by John D

Italian Harpsichord-Building in the 16th and 17th Centuries by John D. Shortridge (REPRINTED WITH CHANGES—1970) CONTRIBUTIONS FROM THE MUSEUM OF HISTORY AND TECHNOLOGY UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM BULLETIN 225 · Paper 15, Pages 93–107 SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS · WASHINGTON, D.C. · 1970 Figure 1.—OUTER CASE OF ALBANA HARPSICHORD. Italian Harpsichord-Buildingin the 16th and 17th Centuries By John D. Shortridge The making of harpsichords flourished in Italy throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. The Italian instruments were of simpler construction than those built by the North Europeans, and they lacked the familiar second manual and array of stops. In this paper, typical examples of Italian harpsichords from the Hugo Worch Collection in the United States National Museum are described in detail and illustrated. Also, the author offers an explanation for certain puzzling variations in keyboard ranges and vibrating lengths of strings of the Italian harpsichords. THE AUTHOR: John D. Shortridge is associate curator of cultural history in the United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution. PERHAPS the modern tendency to idealize progress has been responsiblefor the neglect of Italian harpsichords and virginals during the present day revival of interest in old musical instruments. Whatever laudable traits the Italian builders may have had, they cannot be considered to have been progressive. Their instruments of the mid-16th century hardly can be distinguished from those made around 1700. During this 150 years the pioneering Flemish makers added the four-foot register, a second keyboard, and lute and buff stops to their instruments. However, the very fact that the Italian builders were unwilling to change their models suggests that their instruments were good enough to demand no further improvements. -

Tonal Quality of the Clavichord : the Effect of Sympathetic Strings Christophe D’Alessandro, Brian Katz

Tonal quality of the clavichord : the effect of sympathetic strings Christophe d’Alessandro, Brian Katz To cite this version: Christophe d’Alessandro, Brian Katz. Tonal quality of the clavichord : the effect of sympathetic strings. Intl Symp on Musical Acoustics (ISMA), 2004, Nara, Unknown Region. pp.21–24. hal- 01789802 HAL Id: hal-01789802 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01789802 Submitted on 21 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Musical Acoustics, March 31st to April 3rd 2004 (ISMA2004), Nara, Japan 1-P1-7 Tonal quality of the clavichord: the effect of sympathetic strings Christophe d'Alessandro & Brian F.G. Katz LIMSI-CNRS, BP133 F-91403 Orsay, France [email protected], [email protected] Abstract part of the strings the “played strings”. Only few works have included efforts specifically devoted to the In the clavichord, unlike the piano, the slanting strings acoustics of the clavichord [2][3][4]. Experiments with between the bridge and the hitch pins are not damped physical modeling synthesis of the clavichord are with felt. The effect of these “sympathetic strings” on described in [5]. -

Cathedral Chimestm

32 Cathedral ChimesTM A fresh approach to organ chimes Patented striker design is quiet, efficient, and virtually maintenance free. Dampers lift off tubes for as long as a key is held. Solid state relay with fixed strike pulse timing is included. Very easy to install in most organs. Custom keying cables are available to further simplify installation. Beautiful brushed brass tubes or aluminum chime bars. Also available as an “action only” for use with older chime tubes. Some years ago, Peterson set out to see what could Beautiful satin-finished brass chime tubes or silver be done to modernize and improve the traditional colored anodized aluminum bars are precision tuned tubular chimes that have been part of fine organs for with Peterson stroboscopic tuning instruments and decades. It was quickly realized that chimes and chime engineered for optimal harmonic development. A actions were still being made the same way they had Peterson chime rail and relay may also be provided been made 40 years earlier. They still had the same as an “action only” to replace an old, defective action problems with imprecise tuning; uneven and difficult to while utilizing original tubes having diameters up to adjust actions; heavy and hard-to-install cables; sparking 1-1/2 inches. contacts; and a host of other pitfalls all too well known The Cathedral Chimes system’s easy connection to organbuilders and service technicians. A subsequent to almost any pipe organ requires only a small cable, two-year development program was begun to address making it practical to display chimes and to better and overcome these concerns, and ultimately the TM capitalize on their beautiful appearance. -

A New History of the Carillon

A New History of the Carillon TIFFANY K. NG Rombouts, Luc. Singing Bronze: A History of Carillon Music. Translated by Com- municationwise. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2014, 368 pp. HE CARILLON IS HIDDEN IN plain sight: the instrument and its players cannot be found performing in concert halls, yet while carillonneurs and Tkeyboards are invisible, their towers provide a musical soundscape and focal point for over six hundred cities, neighborhoods, campuses, and parks in Europe, North America, and beyond. The carillon, a keyboard instrument of at least two octaves of precisely tuned bronze bells, played from a mechanical- action keyboard and pedalboard, and usually concealed in a tower, has not received a comprehensive historical treatment since André Lehr’s The Art of the Carillon in the Low Countries (1991). A Dutch bellfounder and campanologist, Lehr contributed a positivist history that was far-ranging and thorough. In 1998, Alain Corbin’s important study Village Bells: Sound and Meaning in the Nineteenth-Century French Countryside (translated from the 1994 French original) approached the broader field of campanology as a history of the senses.1 Belgian carillonneur and musicologist Luc Rombouts has now compiled his extensive knowledge of carillon history in the Netherlands, Belgium, and the United States, as well as of less visible carillon cultures from Curaçao to Japan, into Singing Bronze: A History of Carillon Music, the most valuable scholarly account of the instrument to date. Rombouts’s original Dutch book, Zingend Brons (Leuven: Davidsfonds, 2010), is the more comprehensive version of the two, directed at a general readership in the Low Countries familiar with carillon music, and at carillonneurs and music scholars. -

Basic Music Course: Keyboard Course

B A S I C M U S I C C O U R S E KEYBOARD course B A S I C M U S I C C O U R S E KEYBOARD COURSE Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah © 1993 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Updated 2004 English approval: 4/03 CONTENTS Introduction to the Basic Music Course .....1 “In Humility, Our Savior”........................28 Hymns to Learn ......................................56 The Keyboard Course..................................2 “Jesus, the Very Thought of Thee”.........29 “How Gentle God’s Commands”............56 Purposes...................................................2 “Jesus, Once of Humble Birth”..............30 “Jesus, the Very Thought of Thee”.........57 Components .............................................2 “Abide with Me!”....................................31 “Jesus, Once of Humble Birth”..............58 Advice to Students ......................................3 Finding and Practicing the White Keys ......32 “God Loved Us, So He Sent His Son”....60 A Note of Encouragement...........................4 Finding Middle C.....................................32 Accidentals ................................................62 Finding and Practicing C and F...............34 Sharps ....................................................63 SECTION 1 ..................................................5 Finding and Practicing A and B...............35 Flats........................................................63 Getting Ready to Play the Piano -

Keyboard Music Is

Seventeenth-Century Keyboard Music in Dutch- and German-Speaking Europe David Schulenberg (2004, updated 2021) Keyboard music is central to our understanding of the Baroque, particularly in northern Europe, whose great church organs were among the technological and artistic wonders of the age. This essay treats of the distinctive traditions of keyboard music in Germany, Austria, and the Netherlands before the time of Johann Sebastian Bach and other eighteenth-century musicians. Baroque keyboard music followed in a continuous tradition that of the sixteenth century, when for the first time major composers such as William Byrd (1543–1623) in England and Andrea Gabrieli (ca. 1510–1586) in Italy had created repertories of original keyboard music equal in stature to their contributions in other genres. Such compositions joined improvised music and arrangements of vocal and instrumental works as the foundations of keyboard players' repertories. Nevertheless, the actual practice of keyboard players during the Baroque continued to comprise much improvisation. Keyboard players routinely accompanied other musicians, providing what is called the basso continuo through the improvised realization of a figured bass.1 On the relatively rare occasions when solo keyboard music was heard in public, it often took the form of improvised preludes and fantasias, as in church services and the occasional public organ recital. Hence, much of the Baroque repertory of written compositions for solo keyboard instruments consists of idealized improvisations. The capacity of keyboard instruments for self-sufficient polyphonic playing also made them uniquely suited for the teaching and study of composition. Thus a second large category of seventeenth-century keyboard music comprises models for good composition, especially in learned, if somewhat archaic, styles of counterpoint. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

Sound and Science of Musical Instruments Schubert Club Museum About Us

Schubert Club Museum Teacher Guide Sound and Science of Musical Instruments Schubert Club Museum About Us About Schubert Club Fun Facts! Schubert Club is one of the nation’s most vibrant Schubert Club is the oldest arts organization in music organizations, enriching Minnesota with the midwest and one of the oldest in the country. dynamic concerts, music education programs, and museum exhibits. Schubert Club Museum houses a collection of musical instruments and original manuscripts Schubert Club Museum is located in downtown from all over the globe. Saint Paul’s historic Landmark Center. Schubert Club was founded in 1882 by a group of women, “The Ladies Musicale”, who wanted to cultivate a lively music scene in Saint Paul focused on recitals. They later changed their name to The Schubert Club to honor composer Franz Schubert. You can play historical keyboards and view manuscripts from famous composers—including a handwritten letter from Mozart! Our Project CHEER program provides free music lessons to kids who would not otherwise be able to prioritize private music lessons. Our name may make us sound like a “club”, but Schubert Club welcomes everyone to enjoy our concerts, education programs, and museum. Schubert Club is a part of the Arts Partnership with Minnesota Opera, The Ordway, and Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, and is a nonprofit organization. Museum school tours are filled with interactive activities that are inspired by making music, exploring how instruments work, and discovering For more information about Schubert Club visit the history and cultures behind the music. www.schubert.org Schubert Club Museum Plan a Trip FAQ Field Trip Checklist Is Schubert Club Museum accessible? Our build- BEFORE ing, Landmark Center is accessible for persons with mobili- ty challenges by way of the entrance from Market Street on the East side of the building.