Lieutenant Cecil Halliday Abercrombie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marrickville Cricket Club

Marrickville Cricket Club Season Report 2017-18 Thank you sponsors Financial report A word from our sponsors - Sydney Airport and Canterbury Hurlstone Park RSL Marrickville Cricket Club is very grateful to have the support and sponsorship of Sydney Airport and Canterbury Hurlstone Park RSL. The sponsorship helps young cricketers and their families with reduced player registration fees and basic cricket gear such as shirts, hats, balls and drink bottles. For the past seven years, Sydney Airport has Canterbury Hurlstone Park RSL Club is very been a major sponsor of the Marrickville pleased to support Marrickville Cricket Club. Cricket Club. We are proud of our investment in the local The MCC is an important local sporting community, especially when it supports grass- organisation providing training, education roots organisations doing great things with and skills for the young cricket players in our local children. community. Whether it’s helping local cricket players Our organisation is proud to support the with hats and shirts, funding educators for parents, coaches and volunteers at the MCC after-school fitness sessions to help promote who provide vital skills such as leadership and healthy lifestyles, or assisting with funding teamwork to our kids. for sheet music, tuition and software, helping schools run quality music ensembles, we’re Nearly 31,000 people work at Sydney Airport thrilled to be ‘reinvesting for life’ in our across 800 businesses and many of these community. people live within our local community. Our relationship with Marrickville Cricket As part of our community investment Club recently grew as we work together to program, the airport prioritises working with promote hospitality training for parents, local sporting organisations, businesses and players and volunteers through our CHP charities to support their objectives. -

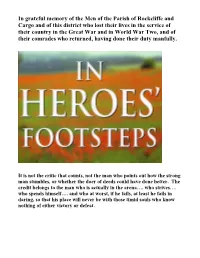

In Grateful Memory of the Men of the Parish of Rockcliffe and Cargo And

In grateful memory of the Men of the Parish of Rockcliffe and Cargo and of this district who lost their lives in the service of their country in the Great War and in World War Two, and of their comrades who returned, having done their duty manfully. It is not the critic that counts, not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or whether the doer of deeds could have done better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena…. who strives…. who spends himself…. and who at worst, if he fails, at least he fails in daring, so that his place will never be with those timid souls who know nothing of either victory or defeat. At the going down of the sun, And in the morning We will remember them. A cross of sacrifice stands in all Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries on the Western Front. The War Memorial of the Parish of Rockcliffe and Cargo. It is 2010. In far off Afghanistan young men and women of various nations are putting their lives at risk as they struggle to defeat a tenacious enemy. We receive daily reports of the violent death of some while still in their teens. Others, of whom we hear little, are horribly maimed for life. We here, in the relative safety of the countries we call The British Isles, are free to discuss from our armchair or pub stool the rights and wrongs of such a conflict. That right of free speech, whatever our opinion or conclusion, was won for us by others, others who are not unlike today’s almost daily casualties of a distant war. -

Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale

Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale - Day 2 Wednesday 05 December 2012 10:30 Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers The Clive Pavilion Ludlow Racecourse Ludlow SY8 2BT Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers (Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale - Day 2) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1001 Rugby League tickets, postcards and handbooks Rugby 1922 S C R L Rugby League Medal C Grade Premiers awarded League Challenge Cup Final tickets 6th May 1950 and 28th to L McAuley of Berry FC. April 1956 (2 tickets), 3 postcards – WS Thornton (Hunslet), Estimate: £50.00 - £65.00 Hector Crowther and Frank Dawson and Hunslet RLFC, Hunslet Schools’ Rugby League Handbook 1963-64, Hunslet Schools’ Rugby Union 1938-39 and Leicester City v Sheffield United (FA Cup semi-final) at Elland Road 18th March 1961 (9) Lot: 1002 Estimate: £20.00 - £30.00 Keighley v Widnes Rugby League Challenge Cup Final programme 1937 played at Wembley on 8th May. Widnes won 18-5. Folded, creased and marked, staple rusted therefore centre pages loose. Lot: 1009 Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 A collection of Rugby League programmes 1947-1973 Great Britain v New Zealand 20th December 1947, Great Britain v Australia 21st November 1959, Great Britain v Australia 8th October 1960 (World Cup Series), Hull v St Helens 15th April Lot: 1003 1961 (Challenge Cup semi-final), Huddersfield v Wakefield Rugby League Championship Final programmes 1959-1988 Trinity 19th May 1962 (Championship final), Bradford Northern including 1959, 1960, 1968, 1969, 1973, 1975, 1978 and -

Vollume 20, No 4 2004

But I asked him to pick me up a Big Mac PEER PRESSURE! Just say yes School Nurse seeks funds for staff special needs JJ makes his mark on the school No blushes - just blooming magic! Not calves - cows! And I was onto the green in five! CONTENTS CAPTAINS OF SCHOOL 2 SWIM TEAM 66 STAFF NOTES 3 BADMINTON / SAILING 67 VALETE 4 GOLF REPORT 2004 68 OBITUARY - REVD TREVOR STEVENS 7 F IT B A ’ 69 S P E E C H DAY 8 SKI SEASON 2003-2004 70 SCHOOL HOUSES 10 GIRLS’TENNIS/CYCLING 71 RILEY HOUSE 10 BOYS' TENNIS 72 FREELAND HOUSE 12 A HAWK IN WINTER 73 NICOL HOUSE 14 EQUESTRIANISM 74 RUTHVEN HOUSE 16 SIMPSON HOUSE 18 SHOOTING 75 THORNBANK HOUSE 20 SUB AQUA 76 WOODLANDS HOUSE 22 PAST. PRESENT AND FUTURE 78 HEADMASTER S SUMMER MUSIC 2 4 A R M Y 86 MUSIC 26 TA B O R 88 THE CHAPEL CHOIR TOUR OF VISITING LECTURERS 89 THE NORTH OF ENGLAND 28 P R A G U E 90 NATIONAL YOUTH CHOIR OF SCOTLAND 29 MONTPELLIER 92 P IP IN G 30 STRATHALLIAN DAY TWELFTH NIGHT OR WHAT YOU WILL 32 /LAUNCH OF NEW WEBSITE 93 LES MISERABLES 3 4 SIXTH FORM COMMON ROOM REPORT 03-04 94 SENIOR HOUSE DRAMA 3 7 SIXTH FORM 95 SPEECH & DRAMA 3 8 TRIATHLON / IV AND V FORM REELS 96 ESSAY COMPETITION 39 WOODFAIR 97 S A LV E T E 04 40 SIXTH FORM BALL 2004 98 ART & DESIGN 4 2 SIXTH FORM 99 DESIGN & TECHNOLOGY 4 8 STRATHSTOCK 2004 100 C R IC K E T 52 A R T S H O W / FASHION SHOW EXTRAVAGANZA 102 RUGBY 56 B U R N S ’ S U P P E R MARATHON WOMAN 59 /STRATHMORE CHALLENGE 104 CROSS COUNTRY AND ATHLETICS 2004 60 FORENSIC SCIENCE TASTER DAY BOYS' HOCKEY 62 /MILLPORT 105 G IR L S ’ H O C K E Y 63 OBITUARIES 106 GIRLS’ HOCKEY TOUR 2004 64 VALETE 04 110 Volume XX No. -

Ships!), Maps, Lighthouses

Price £2.00 (free to regular customers) 03.03.21 List up-dated Winter 2020 S H I P S V E S S E L S A N D M A R I N E A R C H I T E C T U R E 03.03.20 Update PHILATELIC SUPPLIES (M.B.O'Neill) 359 Norton Way South Letchworth Garden City HERTS ENGLAND SG6 1SZ (Telephone; 01462-684191 during my office hours 9.15-3.15pm Mon.-Fri.) Web-site: www.philatelicsupplies.co.uk email: [email protected] TERMS OF BUSINESS: & Notes on these lists: (Please read before ordering). 1). All stamps are unmounted mint unless specified otherwise. Prices in Sterling Pounds we aim to be HALF-CATALOGUE PRICE OR UNDER 2). Lists are updated about every 12-14 weeks to include most recent stock movements and New Issues; they are therefore reasonably accurate stockwise 100% pricewise. This reduces the need for "credit notes" and refunds. Alternatives may be listed in case some items are out of stock. However, these popular lists are still best used as soon as possible. Next listings will be printed in 4, 8 & 12 months time so please indicate when next we should send a list on your order form. 3). New Issues Services can be provided if you wish to keep your collection up to date on a Standing Order basis. Details & forms on request. Regret we do not run an on approval service. 4). All orders on our order forms are attended to by return of post. We will keep a photocopy it and return your annotated original. -

November 2014

FREE November 2014 OFFICIAL PROGRAMME www.worldrugby.bm GOLF TouRNAMENt REFEREEs LIAIsON Michael Jenkins Derek Bevan mbe • John Weale GROuNds RuCK & ROLL FRONt stREEt Cameron Madeiros • Chris Finsness Ronan Kane • Jenny Kane Tristan Loescher Michael Kane Trevor Madeiros (National Sports Centre) tEAM LIAIsONs Committees GRAPHICs Chief - Pat McHugh Carole Havercroft Argentina - Corbus Vermaak PREsIdENt LEGAL & FINANCIAL Canada - Jack Rhind Classic Lions - Simon Carruthers John Kane, mbe Kim White • Steve Woodward • Ken O’Neill France - Marc Morabito VICE PREsIdENt MEdICAL FACILItIEs Italy - Guido Brambilla Kim White Dr. Annabel Carter • Dr. Angela Marini New Zealand - Brett Henshilwood ACCOMMOdAtION Shelley Fortnum (Massage Therapists) South Africa - Gareth Tavares Hilda Matcham (Classic Lions) Maureen Ryan (Physiotherapists) United States - Craig Smith Sue Gorbutt (Canada) MEMbERs tENt TouRNAMENt REFEREE AdMINIstRAtION Alex O'Neill • Rick Evans Derek Bevan mbe Julie Butler Alan Gorbutt • Vicki Johnston HONORARy MEMbERs CLAssIC CLub Harry Patchett • Phil Taylor C V “Jim” Woolridge CBE Martine Purssell • Peter Kyle MERCHANdIsE (Former Minister of Tourism) CLAssIC GAs & WEbsItE Valerie Cheape • Debbie DeSilva Mike Roberts (Wales & the Lions) Neil Redburn Allan Martin (Wales & the Lions) OVERsEAs COMMENtARy & INtERVIEWs Willie John McBride (Ireland & the Lions) Argentina - Rodolfo Ventura JPR Williams (Wales & the Lions) Hugh Cahill (Irish Television) British Isles - Alan Martin Michael Jenkins • Harry Patchett Rodolfo Ventura (Argentina) -

Les Îles De La Manche ~ the Channel Islands

ROLL OF HONOUR 1 The Battle of Jutland Bank ~ 31st May 1916 Les Îles de la Manche ~ The Channel Islands In honour of our Thirty Six Channel Islanders of the Royal Navy “Blue Jackets” who gave their lives during the largest naval battle of the Great War 31st May 1916 to 1st June 1916. Supplement: Mark Bougourd ~ The Channel Islands Great War Study Group. Roll of Honour Battle of Jutland Les Îles de la Manche ~ The Channel Islands Charles Henry Bean 176620 (Portsmouth Division) Engine Room Artificer 3rd Class H.M.S. QUEEN MARY. Born at Vale, Guernsey 12 th March 1874 - K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 42) Wilfred Severin Bullimore 229615 (Portsmouth Division) Leading Seaman H.M.S. INVINCIBLE. Born at St. Sampson, Guernsey 30 th November 1887 – K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 28) Wilfred Douglas Cochrane 194404 (Portsmouth Division) Able Seaman H.M.S. BLACK PRINCE. Born at St. Peter Port, Guernsey 30 th September 1881 – K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 34) Henry Louis Cotillard K.20827 (Portsmouth Division) Stoker 1 st Class H.M.S. BLACK PRINCE. Born at Jersey, 2 nd April 1893 – K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 23) John Alexander de Caen 178605 (Portsmouth Division) Petty Officer 1 st Class H.M.S. INDEFATIGABLE. Born at St. Helier, Jersey 7th February 1879 – K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 37) The Channel Islands Great War Study Group. - 2 - Centenary ~ The Battle of Jutland Bank www.greatwarci.net © 2016 ~ Mark Bougourd Roll of Honour Battle of Jutland Les Îles de la Manche ~ The Channel Islands Stanley Nelson de Quetteville Royal Canadian Navy Lieutenant (Engineer) H.M.S. -

Newspaper Index S

Watt Library, Greenock Newspaper Index This index covers stories that have appeared in newspapers in the Greenock, Gourock and Port Glasgow area from the start of the nineteenth century. It is provided to researchers as a reference resource to aid the searching of these historic publications which can be consulted, preferably by prior appointment, at the Watt Library, 9 Union Street, Greenock. Subject Entry Newspaper Date Page Sabbath Alliance Report of Sabbath Alliance meeting. Greenock Advertiser 28/01/1848 Sabbath Evening School, Sermon to be preached to raise funds. Greenock Advertiser 15/12/1820 1 Greenock Sabbath Morning Free Sabbath Morning Free Breakfast restarts on the first Sunday of October. Greenock Telegraph 21/09/1876 2 Breakfast Movement Sabbath Observation, Baillie's Orders against trespassing on the Sabbath Greenock Advertiser 10/04/1812 1 Cartsdyke Sabbath School Society, General meeting. Greenock Advertiser 26/10/1819 1 Greenock Sabbath School Society, Celebrations at 37th anniversary annual meeting - report. Greenock Advertiser 06/02/1834 3 Greenock Sabbath School Society, General meeting 22nd July Greenock Advertiser 22/07/1823 3 Greenock Sabbath School Society, Sabbath School Society - annual general meeting. Greenock Advertiser 03/04/1821 1 Greenock Sabbath School Union, 7th annual meeting - report. Greenock Advertiser 28/12/1876 2 Greenock Sabbath School Union, 7th annual meeting - report. Greenock Telegraph 27/12/1876 3 Greenock Sailcolth Article by Matthew Orr, Greenock, on observations on sail cloth and sails -

SS Hazelwood First World War Site Report

Forgotten Wrecks of the SS Hazelwood First World War Site Report 2018 Maritime Archaeology Trust: Forgotten Wrecks of the First World War Site Report SS Hazelwood (2018) FORGOTTEN WRECKS OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR SS HAZELWOOD SITE REPORT Page 1 of 16 Maritime Archaeology Trust: Forgotten Wrecks of the First World War Site Report SS Hazelwood (2018) Table of Contents i Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................ 2 ii Copyright Statement ........................................................................................................................ 3 iii List of Figures .................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Project Background ............................................................................................................................ 3 2. Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Desk Based Historic Research ....................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Associated Artefacts ..................................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Site Visit/Fieldwork ....................................................................................................................... 5 3. Vessel Biography: -

My War at Sea 1914–1916

http://www.warletters.net My War at Sea: 1914–1916 Heathcoat S. Grant Edited by Mark Tanner Published by warletters.net http://www.warletters.net Copyright First published by WarLetters.net in 2014 17 Regent Street Lancaster LA1 1SG Heathcoat S. Grant © 1924 Published courtesy of the Naval Review. Philip J. Stopford © 1918 Published courtesy of the Naval Review. Philip Malet de Carteret letters copyright © Charles Malet de Carteret 2014. Philip Malet de Carteret introduction and notes copyright © Mark Tanner 2014. ISBN: 978-0-9566902-6-5 (Kindle) ISBN: 978-0-9566902-7-2 (Epub) The right of Heathcoat S. Grant, Philip J. Stopford, Philip Malet de Carteret and Mark Tanner to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. This publication may be shared and distributed on a non-commercial basis provided that the work remains in its entirety and no changes are made. Any other use requires the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Naval Review c/o http://www.naval-review.com Charles Malet de Carteret c/o St Quen’s Manor, Jersey Mark Tanner c/o http://warletters.net http://www.warletters.net Contents Contents 4 Preface 5 1: From England to South America 7 2: German Ships Approaching 12 3: The Coronel Action 17 4: The Defence of the Falklands 19 5: The Battle of the Falklands 25 6: On Patrol 29 7: To the Dardanelles 33 8: Invasion Preparations 41 9: Gallipoli Landings 45 10: At Cape Helles 49 11: Back to Anzac 51 12: The Smyrna Patrol 56 13: The Suvla Landings 61 14: The Smyrna Patrol (Continued) 63 15: Sick Leave in Malta 67 16: Evacuation 69 17: Operations Against Smyrna 75 18: Report on Operations 82 19: Leaving for Home 85 APPENDICES 87 1: Canopus Officers 87 2: Heathcoat S. -

Scotland Players

%./{/yo«// • RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION Look for the Gin in the six-sided bottle, and take home a bottle to-day ! MAXIMUM PRICES IN U.K. Bottle 33z9 Half Bot:!a VH • Qtr. Bottle 9'2 • Miniature 3/7 M^/ief/ieri/cu want A SINGLE JOIST RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION A COMPLETE BUILDING VERSUS STEELWORK SERVICE TWICKENHAM 21st March 1953 RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION 1952-53 PATRON: H.M. THE QUEEN President: P. M. HOLMAN (Cornwall) Vice-Presidents: IMPiMNKEN-• ltd J. BRUNTON, D.S.O.J M.C. (Northumberland) W. C. RAMSAY (Middlesex) CONSTRUCTIONAL ENGINEERS Hon. Treasurer-. W. C. RAMSAY Secretary: F. D. PRENTICE -- IRON & STEEL STOCKHOLDERS J • - . - SCOTTISH RUGBY UNION .TELEPHONE I EEEE 5 TELEGRAMS 2-7 3 O I (20 LINES) •• • •» •• "SECTIONS LEEDS President: F. J. C MOFFAT (Watsonians) Vice-President: M. A. ALLAN (Glasgow Academicals) Secretary and Treasurer: F. A. WRIGHT 3 This Year's '"N Interna tidhals Down shines the hilarating picture sun and down goes are (left to right) Adkins in Eng Holmes, Lewis, land's match with Kendall - Carpenter France three weeks and Wilson. The ago. Other English French tackier men in this ex , is Marcel Celaya. SCOTLAND v WALES The great Welsh forward Roy John handing off the Scottish captain, A. F. Dorward, in the match at Murrayfield. Wales won by one penalty goal and three tries (12 points) to nil. WALES v. ENGLAND Thv new Welsh wing in action . Gareth Griffiths, threatened by his opposite number, J. E. Woodward, about to cross-kick. Malcolm Thomas of Newport can be seen between the two. IRELAND v. -

'The Admiralty War Staff and Its Influence on the Conduct of The

‘The Admiralty War Staff and its influence on the conduct of the naval between 1914 and 1918.’ Nicholas Duncan Black University College University of London. Ph.D. Thesis. 2005. UMI Number: U592637 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592637 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS Page Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Abbreviations 6 Introduction 9 Chapter 1. 23 The Admiralty War Staff, 1912-1918. An analysis of the personnel. Chapter 2. 55 The establishment of the War Staff, and its work before the outbreak of war in August 1914. Chapter 3. 78 The Churchill-Battenberg Regime, August-October 1914. Chapter 4. 103 The Churchill-Fisher Regime, October 1914 - May 1915. Chapter 5. 130 The Balfour-Jackson Regime, May 1915 - November 1916. Figure 5.1: Range of battle outcomes based on differing uses of the 5BS and 3BCS 156 Chapter 6: 167 The Jellicoe Era, November 1916 - December 1917. Chapter 7. 206 The Geddes-Wemyss Regime, December 1917 - November 1918 Conclusion 226 Appendices 236 Appendix A.