Implementation of Emergency Housing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Invests R101m in Housing

21 August - 3 September 2015 Your FREE Newspaper METROezasegagasini www.durban.gov.za NEW FACELIFT WORLD TRADING FOR ISIPINGO CLASS STALLS CENTRE SPORT HUB News: Page 3 News: Page 7 Sports: Page 12 City invests R101m in housing CHARMEL PAYET said. The pilot phase, Phase 1A, HE Executive was at an advanced stage Committee on with 482 top structures on Tuesday, 18 August fully serviced sites. 2015 approved ad- The funding shortfall of ditional funding of R101 million is to ensure TR101 million to ensure the completion of the eight sub- first phase of the Cornubia phases in Phase 1, of which Integrated Human Settle- one, Phase 1B, was already ment Development would at implementation stage. be completed. Additional funds are need- City Manager Sibusiso ed to complete Phase 1B. Sithole said funding had to Currently three contractors be approved to ensure the are engaged with the imple- City was able to meet their mentation of 2 186 sites. housing obligations which Of this 803 sites are ready included the relocation of for top structure construc- several identified transit tion, 741 by another con- camps at the site.“There is tractor will be completed a sense of urgency in this this month while the third matter as we have been contractor will be imple- dealing with it for months. If menting 642 serviced sites. we don’t find a solution we Top structures will be com- will sit with this infrastruc- pleted by April next year. ture which will be wasteful Attempts to find solutions expenditure which we don’t to address the shortfall were want,” he said. -

South Africa-Violence-Fact Finding Mission Report-1990-Eng

SIGNPOSTS TO PEACE An Independent Survey of the Violence in Natal, South Africa By The International Commission of Jurists SIGNPOSTS TO PEACE An Independent Survey of the Violence in Natal, South Africa By The International Commission of Jurists International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) Geneva, Switzerland Members of the Mission: John Macdonald Q.C. (United Kingdom) Christian Ahlund (Sweden) Jeremy Sarkin (South Africa) ttR-?-£P - 2'^a *S\G PREFACE The International Commission of Jurists, at the suggestion of many lawyers in South Africa, sent a mission to Natal at the end of August 1990 to investigate the rampant violence which has torn the Province apart for upwards of four years. Over a period of two weeks, the mission concentrated its efforts on developing an in-depth understanding of the violence which continues to plague Natal. Stringent time constraints did not permit them to investigate the situation in the Transvaal where the violence has now spread. The mission held meetingjs with a variety of organisations and individuals representing aE sides involved with the violence, as well as with independent monitors and observers. The mission met Government ministers Pik Botha (Foreign Affairs) and Adrian Vlok (Law and order) and talked with the African National Congress (ANQ leaders in Natal as-well as with Walter Sisulu oftheANCNationalExecutive Committee. They saw Chief MinisterButhelexi, who is the President oflnkatha and ChiefMinister ofKwa Zulu as well as the Pea Mtetwa, the Kwa Zulu Minister of Justice. In addition, they had discussions with the Attorney General of Natal and his deputies, The Regional Commissioner and other high ranking officers of the South African Police (SAP). -

R603 (Adams) Settlement Plan & Draft Scheme

R603 (ADAMS) SETTLEMENT PLAN & DRAFT SCHEME CONTRACT NO.: 1N-35140 DEVELOPMENT PLANNING ENVIRONMENT AND MANAGEMENT UNIT STRATEGIC SPATIAL PLANNING BRANCH 166 KE MASINGA ROAD DURBAN 4000 2019 FINAL REPORT R603 (ADAMS) SETTLEMENT PLAN AND DRAFT SCHEME TABLE OF CONTENTS 4.1.3. Age Profile ____________________________________________ 37 4.1.4. Education Level ________________________________________ 37 1. INTRODUCTION _______________________________________________ 7 4.1.5. Number of Households __________________________________ 37 4.1.6. Summary of Issues _____________________________________ 38 1.1. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT ____________________________________ 7 4.2. INSTITUTIONAL AND LAND MANAGEMENT ANALYSIS ___________________ 38 1.2. PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT ______________________________________ 7 4.2.1. Historical Background ___________________________________ 38 1.3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ________________________________________ 7 4.2.2. Land Ownership _______________________________________ 39 1.4. MILESTONES/DELIVERABLES ____________________________________ 8 4.2.3. Institutional Arrangement _______________________________ 40 1.5. PROFESSIONAL TEAM _________________________________________ 8 4.2.4. Traditional systems/practices _____________________________ 41 1.6. STUDY AREA _______________________________________________ 9 4.2.5. Summary of issues _____________________________________ 42 1.7. OUTLINE OF THE REPORT ______________________________________ 10 4.3. SPATIAL TRENDS ____________________________________________ 42 2. LEGISLATIVE -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report

VOLUME THREE Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction to Regional Profiles ........ 1 Appendix: National Chronology......................... 12 Chapter 2 REGIONAL PROFILE: Eastern Cape ..................................................... 34 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Eastern Cape........................................................... 150 Chapter 3 REGIONAL PROFILE: Natal and KwaZulu ........................................ 155 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in Natal, KwaZulu and the Orange Free State... 324 Chapter 4 REGIONAL PROFILE: Orange Free State.......................................... 329 Chapter 5 REGIONAL PROFILE: Western Cape.................................................... 390 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Western Cape ......................................................... 523 Chapter 6 REGIONAL PROFILE: Transvaal .............................................................. 528 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Transvaal ...................................................... -

Between States of Emergency

BETWEEN STATES OF EMERGENCY PHOTOGRAPH © PAUL VELASCO WE SALUTE THEM The apartheid regime responded to soaring opposition in the and to unban anti-apartheid organisations. mid-1980s by imposing on South Africa a series of States of The 1985 Emergency was imposed less than two years after the United Emergency – in effect martial law. Democratic Front was launched, drawing scores of organisations under Ultimately the Emergency regulations prohibited photographers and one huge umbrella. Intending to stifle opposition to apartheid, the journalists from even being present when police acted against Emergency was first declared in 36 magisterial districts and less than a protesters and other activists. Those who dared to expose the daily year later, extended to the entire country. nationwide brutality by security forces risked being jailed. Many Thousands of men, women and children were detained without trial, photographers, journalists and activists nevertheless felt duty-bound some for years. Activists were killed, tortured and made to disappear. to show the world just how the iron fist of apartheid dealt with The country was on a knife’s edge and while the state wanted to keep opposition. the world ignorant of its crimes against humanity, many dedicated The Nelson Mandela Foundation conceived this exhibition, Between journalists shone the spotlight on its actions. States of Emergency, to honour the photographers who took a stand On 28 August 1985, when thousands of activists embarked on a march against the atrocities of the apartheid regime. Their work contributed to the prison to demand Mandela’s release, the regime reacted swiftly to increased international pressure against the South African and brutally. -

Experiences of People Affected by Rabies in Ethekwini District in the Province of Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa

Experiences of people affected by rabies in Ethekwini district in the province of Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa Jeffrey Mduduzi Hadebe1, Maureen Nokuthula Sibiya2 1. Durban University of Technology - Steve Biko Campus, Nursing. 2. Durban University of Technology, Faculty of Health Sciences. Abstract Background: South Africa is one of the countries in Africa adversely affected by rabies, a notifiable disease which can be fatal. Fatalities can be prevented if health care is sought timeously and people are educated about the disease. The Province of Kwa- Zulu-Natal, in particular, has had rabies outbreaks in the past which have led to loss of many lives and devastation of entire families. Objective: The aim of the study was to explore the experiences of people affected by rabies in the eThekwini district of Kwa- Zulu-Natal, South Africa. Methods: The study was guided by a qualitative, exploratory, descriptive design. The sample was purposively selected, and a semi-structured interview was used to collect data from people affected by rabies in the eThekwini district. Data saturation was reached after 12 participants were interviewed. Data was analysed by using Tesch’s eight steps of thematic analysis. Results: The themes included family stability and support structures, exposure to risk factors and risky practices, factors that hindered participants from seeking health care assistance, limited knowledge about rabies and the effects of rabies. Conclusion: It was evident that participants experienced many challenges during their rabies exposure. Individuals, who were directly affected by rabies through contact with rabid animals, were expected to take responsibility for their own lives. Keywords: Rabies, South Africa, qualitative research. -

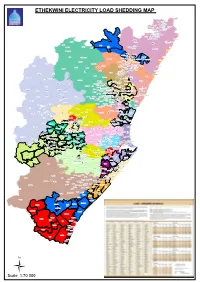

Ethekwini Electricity Load Shedding Map

ETHEKWINI ELECTRICITY LOAD SHEDDING MAP Lauriston Burbreeze Wewe Newtown Sandfield Danroz Maidstone Village Emona SP Fairbreeze Emona Railway Cottage Riverside AH Emona Hambanathi Ziweni Magwaveni Riverside Venrova Gardens Whiteheads Dores Flats Gandhi's Hill Outspan Tongaat CBD Gandhinagar Tongaat Central Trurolands Tongaat Central Belvedere Watsonia Tongova Mews Mithanagar Buffelsdale Chelmsford Heights Tongaat Beach Kwasumubi Inanda Makapane Westbrook Hazelmere Tongaat School Jojweni 16 Ogunjini New Glasgow Ngudlintaba Ngonweni Inanda NU Genazano Iqadi SP 23 New Glasgow La Mercy Airport Desainager Upper Bantwana 5 Redcliffe Canelands Redcliffe AH Redcliff Desainager Matata Umdloti Heights Nellsworth AH Upper Ukumanaza Emona AH 23 Everest Heights Buffelsdraai Riverview Park Windermere AH Mount Moreland 23 La Mercy Redcliffe Gragetown Senzokuhle Mt Vernon Oaklands Verulam Central 5 Brindhaven Riyadh Armstrong Hill AH Umgeni Dawncrest Zwelitsha Cordoba Gardens Lotusville Temple Valley Mabedlane Tea Eastate Mountview Valdin Heights Waterloo village Trenance Park Umdloti Beach Buffelsdraai Southridge Mgangeni Mgangeni Riet River Southridge Mgangeni Parkgate Southridge Circle Waterloo Zwelitsha 16 Ottawa Etafuleni Newsel Beach Trenance Park Palmview Ottawa 3 Amawoti Trenance Manor Mshazi Trenance Park Shastri Park Mabedlane Selection Beach Trenance Manor Amatikwe Hillhead Woodview Conobia Inthuthuko Langalibalele Brookdale Caneside Forest Haven Dimane Mshazi Skhambane 16 Lower Manaza 1 Blackburn Inanda Congo Lenham Stanmore Grove End Westham -

Victim Findings ABRAHAMS, Derrek (30), a Street Committee Me M B E R, Was Shot Dead by Members of the SAP at Gelvandale, Port Elizabeth, on 3 September 1990

Vo l u m e S E V E N ABRAHAMS, Ashraf (7), was shot and injured by members of the Railway Police on 15 October 1985 in Athlone, in the TRO J A N HOR S EI N C I D E N T , CAP E TOW N . Victim findings ABRAHAMS, Derrek (30), a street committee me m b e r, was shot dead by members of the SAP at Gelvandale, Port Elizabeth, on 3 September 1990. ■ ABRAHAMS, John (18) (aka 'Gaika'), an MK member, Unknown victims went into exile in 1968. His family last heard from him Many unnamed and unknown South Africans were the in 1975 and has received conflicting information from victims of gross violations of human rights during the the ANC reg a rding his fate. The Commission was Co m m i s s i o n ’s mandate period. Their stories came to unable to establish what happened to Mr Abrahams, the Commission in the stories of other victims and in but he is presumed dead. the accounts of perpetrators of violations. ABRAHAMS, Moegsien (23), was stabbed and stoned to death by a group of UDF supporters in Mitchells Like other victims of political conflict and violence in Plain, Cape Town, on 25 May 1986, during a UDF rally South Africa, they experienced suffering and injury. wh e re it was alleged that he was an informe r. UDF Some died, some lost their homes. Many experienced leaders attempted to shield him from attack but Mr the loss of friends, family members and a livelihood. -

Thesis Hum 2020 Mbokazi Nonzuzo.Pdf

Understanding Childcare Choices amongst Low-Income Employed Mothers in Urban and Rural KwaZulu-Natal By Nonzuzo Mbokazi Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Town Department of Sociology Cape of Supervisors: Professor Elena Moore and Professor Jeremy Seekings UniversityUniversity of Cape Town 2019 i The copyright of this thesis vests Townin the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes Capeonly. of Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Abstract This study explains how low-income employed mothers navigate care strategies for their young children (0-4 years). The study considers the constraints within which they make ‘choices’ about caring for their children using the market, kin and state. In addition, the study argues that these ‘choices’ are immensely constrained and that the low-income employed mothers have no real choice. For many women, the ‘feminisation of the workforce’ – the growing number of women in paid work – has entailed enormous stress and pressure, as they combine strenuous paid work with the demands of mothering. Low-income employed mothers must balance paid with unpaid work, in ways that are different to women who have more resources. This study analyses how women do this within households where gendered roles and a gender hierarchy continue to prevail. In some cases, low-income employed mothers must take on not only do the ‘work’ of managing the household but also the additional ‘work’ of soliciting the fathers for financial support and involvement in at least some aspects of their children’s lives. -

Informal Economy Budget Analysis: Ethekwini Metropolitan Municipality (Durban, South Africa)

WIEGO Working Paper No 34 March 2015 Informal Economy Budget Analysis: eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality (Durban, South Africa) Glen Robbins and Tasmi Quazi WIEGO Working Papers The global research-policy-action network Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) Working Papers feature research that makes either an empirical or theoretical contribution to existing knowledge about the informal economy especially the working poor, their living and work environments and/ or their organizations. Particular attention is paid to policy-relevant research including research that examines policy paradigms and practice. All WIEGO Working Papers are peer reviewed by the WIEGO Research Team and/or external experts. The WIEGO Publication Series is coordinated by the WIEGO Research Team. The Research Reference Group for the WIEGO Informal Economy Budget Analysis was Marty Chen and Francie Lund. The Project was coordinated by Debbie Budlender. A WIEGO Budget Brief based on this Working Paper is also available at www.wiego.org. Budlender, Debbie. 2015. Budgeting and the Informal Economy in Durban, South Africa. WIEGO Budget Brief No. 6. Cambridge, MA, USA: WIEGO. About the Authors: Glen Robbins is an Honorary Research Fellow in the School of Built Environment and Development Studies at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. His research work has focused primarily on matters of urban and regional economic development. He has previously collaborated on research projects with WIEGO, the ILO, UNCTAD and a variety of other public sector, NGO and multi-lateral organizations, both in South Africa and internationally. Tasmi Quazi has worked in research and advocacy around sustainable architecture, development studies, urban planning and design, and informality for the last ten years. -

Provincial Clinics : Listed Alphabetically by Clinic Name

KwaZulu-Natal Clinics Gazetted Name Insitution Name Type Authority Postal Suburb Postal Tel Tel Fax Fax Address Code Code Number Code Number Uthukela District Municipality Acaciavale Clinic Clinic Local P.O. Box 612 Ladysmith 3370 036 6376833 036 6373980 Authority eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Adams Mission Clinic Clinic State P.O. Box Overport 4067 031 9053780 None None Aided 37587 eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Addington Gateway Clinic C Provincial P.O. Box 977 Durban 4000 031 3272000 031 3272805 Clinic C Uthukela District Municipality AE Haviland Memorial Clinic Provincial P.O. Box 137 Weenen 3325 036 3541872 None None Clinic Ugu District Municipality Albersville Satellite Satellite Local P. O. Box 5 PORT 4240 039 688 2192 Clinic Clinic Authority SHEPSTO NE eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Albert Park Satellite Satellite Local DURBAN 4000 031 300 3121 NONE NONE Clinic Clinic Authority Zululand District Municipality Altona Clinic Clinic Provincial P/Bag X0006 Pongola 3170 034 4131707 034 4132304 Umzinyathi District Municipality Amakhabela Clinic Clinic Provincial P/Bag X5562 Greytown 3250 033 4440662 033 4440663 iLembe District Municipality Amandlalathi Clinic Clinic Provincial Private Bag UMVOTI 3268 033 444 0840 033 444 0987 X216 eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Amanzimtoti Clinic Clinic Local P.O. Box 2443 Durban 4000 031 3115598 031 9031720 Authority eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Amaoti Clinic Clinic Provincial P/Bag X13 Mount 4300 031 5195967 031 5195243 Edgecomb e eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality Amatikwe -

Wartime Mobilisation and Post-War Violence in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa

Master Thesis in Peace and Conflict Studies Department of Peace and Conflict Studies Uppsala University “SO THE KILLINGS CONTINUED” Wartime Mobilisation and Post-war Violence in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa SEBASTIAN VAN BAALEN [email protected] Spring 2015 Supervisor: Kristine Höglund To the people of Richmond, Umbumbulu and Bhambayi, who have suffered the burden of violence. 2 Cry the beloved country by Alan Paton There is a lovely road that runs from Ixopo into the hills. These hills are grass-covered and rolling, and they are lovely beyond any singing of it. The road climbs seven miles into them, to Carisbrooke; and from there, if there is no mist, you look down on one of the fairest valleys of Africa. About you there is grass and bracken and you may hear the forlorn crying of the titihoya, one of the birds of the veld. Below you is the valley of the Umzimkulu, on its journey from the Drakensberg to the sea; and beyond and behind the river, great hill after great hill; and beyond and behind them, the mountains of Ingeli and East Griqualand (Paton 1948:2). 3 ABSTRACT Even though the end of war is often expected to lead to the end of political violence, empirical evidence suggests that many post-war countries experience continuous violence. This study explores the issue of post-war violence at the local level and seeks to explain why some communities experience high levels of violence while others do not. By deriving the implications from the theory on elite mobilisation in civil war, I argue that post-war violence is a function of the type of wartime mobilisation that occurs in a community.