Establishment of Babesia Vulpes N. Sp. (Apicomplexa: Babesiidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Babesia Species

Laboratory diagnosis of babesiosis Babesia species Basic guidelines A. Capillary blood should be obtained by fingerstick, or venous blood should be obtained by venipuncture. B. Blood smears, at least two thick and two thin, should be prepared as soon as possible after col- lection. Delay in preparation of the smears can result in changes in parasite morphology and staining characteristics. In Babesia infections, infected red blood cells (rbcs) are normal in size. Typically rings are seen, and they may be vacuolated, pleomorphic or pyriform. Extracellular or tetrad-forms may also be present. Unlike Plasmodium spp., Babesia organisms lack pigment. Rings Rings of Babesia spp. have delicate cytoplasm and are often pleomorphic. Infected rbcs are not enlarged; multiple infection of rbcs can be common. Rings are usually vacuolated and do not produce pigment. Oc- casional classic tetrad-forms (Maltese Cross) or extracellular rings can be present. Rings of Babesia sp. in thick blood smears. Thin, delicate rings of Babesia sp. in a Babesia sp. in a thin blood smear, Thin blood smear showing a cluster of thin blood smear. showing pleomorphic rings and multiply- extracellular rings. infected rbcs. Laboratory diagnosis of babesiosis Babesia species Babesia microti in a thin blood smear. Note Babesia microti in thin blood smears. Notice the vacuolated and pleomorphic rings and multi- the classic “Maltese Cross” tetrad-form in ply-infected rbcs. Notice also there is no pigment present in any of the parasites. the infected rbc in the lower part of the image. Babesia sp. in a thin blood smear stained with Giemsa, showing pleomorphic rings and Babesia sp. -

And Toxoplasmosis in Jackass Penguins in South Africa

IMMUNOLOGICAL SURVEY OF BABESIOSIS (BABESIA PEIRCEI) AND TOXOPLASMOSIS IN JACKASS PENGUINS IN SOUTH AFRICA GRACZYK T.K.', B1~OSSY J.].", SA DERS M.L. ', D UBEY J.P.···, PLOS A .. ••• & STOSKOPF M. K .. •••• Sununary : ReSlIlIle: E x-I1V\c n oN l~ lIrIUSATION D'Ar\'"TIGENE DE B ;IB£,'lA PH/Re El EN ELISA ET simoNi,cATIVlTli t'OUR 7 bxo l'l.ASMA GONIJfI DE SI'I-IENICUS was extracted from nucleated erythrocytes Babesia peircei of IJEMIiNSUS EN ArRIQUE D U SUD naturally infected Jackass penguin (Spheniscus demersus) from South Africo (SA). Babesia peircei glycoprotein·enriched fractions Babesia peircei a ele extra it d 'erythrocytes nue/fies p,ovenanl de Sphenicus demersus originoires d 'Afrique du Sud infectes were obto ined by conca navalin A-Sepharose affinity column natulellement. Des fractions de Babesia peircei enrichies en chromatogrophy and separated by sod ium dodecyl sulphate glycoproleines onl ele oblenues par chromatographie sur colonne polyacrylam ide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE ). At least d 'alfinite concona valine A-Sephorose et separees par 14 protein bonds (9, 11, 13, 20, 22, 23, 24, 43, 62, 90, electrophorese en gel de polyacrylamide-dodecylsuJfale de sodium 120, 204, and 205 kDa) were observed, with the major protein (SOS'PAGE) Q uotorze bandes proleiques au minimum ont ete at 25 kDa. Blood samples of 191 adult S. demersus were tes ted observees (9, 1 I, 13, 20, 22, 23, 24, 43, 62, 90, 120, 204, by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assoy (ELISA) utilizing B. peircei et 205 Wa), 10 proleine ma;eure elant de 25 Wo. -

Essential Function of the Alveolin Network in the Subpellicular

RESEARCH ARTICLE Essential function of the alveolin network in the subpellicular microtubules and conoid assembly in Toxoplasma gondii Nicolo` Tosetti1, Nicolas Dos Santos Pacheco1, Eloı¨se Bertiaux2, Bohumil Maco1, Lore` ne Bournonville2, Virginie Hamel2, Paul Guichard2, Dominique Soldati-Favre1* 1Department of Microbiology and Molecular Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland; 2Department of Cell Biology, Sciences III, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland Abstract The coccidian subgroup of Apicomplexa possesses an apical complex harboring a conoid, made of unique tubulin polymer fibers. This enigmatic organelle extrudes in extracellular invasive parasites and is associated to the apical polar ring (APR). The APR serves as microtubule- organizing center for the 22 subpellicular microtubules (SPMTs) that are linked to a patchwork of flattened vesicles, via an intricate network composed of alveolins. Here, we capitalize on ultrastructure expansion microscopy (U-ExM) to localize the Toxoplasma gondii Apical Cap protein 9 (AC9) and its partner AC10, identified by BioID, to the alveolin network and intercalated between the SPMTs. Parasites conditionally depleted in AC9 or AC10 replicate normally but are defective in microneme secretion and fail to invade and egress from infected cells. Electron microscopy revealed that the mature parasite mutants are conoidless, while U-ExM highlighted the disorganization of the SPMTs which likely results in the catastrophic loss of APR and conoid. Introduction *For correspondence: Toxoplasma gondii belongs to the phylum of Apicomplexa that groups numerous parasitic protozo- Dominique.Soldati-Favre@unige. ans causing severe diseases in humans and animals. As part of the superphylum of Alveolata, the ch Apicomplexa are characterized by the presence of the alveoli, which consist in small flattened single- membrane sacs, underlying the plasma membrane (PM) to form the inner membrane complex (IMC) Competing interest: See of the parasite. -

A Comparative Genomic Study of Attenuated and Virulent Strains of Babesia Bigemina

pathogens Communication A Comparative Genomic Study of Attenuated and Virulent Strains of Babesia bigemina Bernardo Sachman-Ruiz 1 , Luis Lozano 2, José J. Lira 1, Grecia Martínez 1 , Carmen Rojas 1 , J. Antonio Álvarez 1 and Julio V. Figueroa 1,* 1 CENID-Salud Animal e Inocuidad, Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias, Jiutepec, Morelos 62550, Mexico; [email protected] (B.S.-R.); [email protected] (J.J.L.); [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (C.R.); [email protected] (J.A.Á.) 2 Centro de Ciencias Genómicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, AP565-A Cuernavaca, Morelos 62210, Mexico; [email protected] * Correspondence: fi[email protected]; Tel.: +52-777-320-5544 Abstract: Cattle babesiosis is a socio-economically important tick-borne disease caused by Apicom- plexa protozoa of the genus Babesia that are obligate intraerythrocytic parasites. The pathogenicity of Babesia parasites for cattle is determined by the interaction with the host immune system and the presence of the parasite’s virulence genes. A Babesia bigemina strain that has been maintained under a microaerophilic stationary phase in in vitro culture conditions for several years in the laboratory lost virulence for the bovine host and the capacity for being transmitted by the tick vector. In this study, we compared the virulome of the in vitro culture attenuated Babesia bigemina strain (S) and the virulent tick transmitted parental Mexican B. bigemina strain (M). Preliminary results obtained by using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) showed that out of 27 virulence genes described Citation: Sachman-Ruiz, B.; Lozano, and analyzed in the B. -

Package Insert

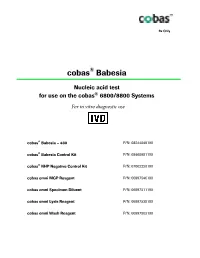

Rx Only ® cobas Babesia Nucleic acid test ® for use on the cobas 6800/8800 Systems For in vitro diagnostic use ® cobas Babesia – 480 P/N: 08244049190 cobas® Babesia Control Kit P/N: 08460981190 cobas® NHP Negative Control Kit P/N: 07002220190 cobas omni MGP Reagent P/N: 06997546190 cobas omni Specimen Diluent P/N: 06997511190 cobas omni Lysis Reagent P/N: 06997538190 cobas omni Wash Reagent P/N: 06997503190 cobas® Babesia Table of contents Intended use ............................................................................................................................ 4 Summary and explanation of the test ................................................................................. 4 Reagents and materials ......................................................................................................... 7 cobas® Babesia reagents and controls ....................................................................................................... 7 cobas omni reagents for sample preparation ........................................................................................ 10 Reagent storage and handling requirements ......................................................................................... 11 Additional materials required ................................................................................................................. 12 Instrumentation and software required ................................................................................................. 12 Precautions and handling requirements -

Extra-Intestinal Coccidians Plasmodium Species Distribution Of

Extra-intestinal coccidians Apicomplexa Coccidia Gregarinea Piroplasmida Eimeriida Haemosporida -Eimeriidae -Theileriidae -Haemosporiidae -Cryptosporidiidae - Babesiidae (Plasmodium) -Sarcocystidae (Sacrocystis) Aconoid (Toxoplasmsa) Plasmodium species Causitive agent of Malaria ~155 species named Infect birds, reptiles, rodents, primates, humans Species is specific for host and •P. falciparum vector •P. vivax 4 species cause human disease •P. malariae No zoonoses or animal reservoirs •P. ovale Transmission by Anopheles mosquito Distribution of Malarial Parasites P. vivax most widespread, found in most endemic areas including some temperate zones P. falciparum primarily tropics and subtropics P. malariae similar range as P. falciparum, but less common and patchy distribution P. ovale occurs primarily in tropical west Africa 1 Distribution of Malaria US Army, 1943 300 - 500 million cases per year 1.5 to 2.0 million deaths per year #1 cause of infant mortality in Africa! 40% of world’s population is at risk Malaria Atlas Map Project http://www.map.ox.ac.uk/index.htm 2 Malaria in the United States Malaria was quite prevalent in the rural South It was eradicated after world war II in an aggressive campaign using, treatment, vector control and exposure control Time magazine - 1947 (along with overall improvement of living Was a widely available, conditions) cheap insecticide This was the CDCs initial DDT resistance misssion Half-life in mammals - 8 years! US banned use of DDT in 1973 History of Malaria Considered to be the most -

Novel and Rapidly Diverging Intergenic Sequences Between Tandem Repeats of the Luciferase Genes in Seven Dinoflagellate Species1

J. Phycol. 42, 96–103 (2005) r 2005 Phycological Society of America DOI: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00165.x NOVEL AND RAPIDLY DIVERGING INTERGENIC SEQUENCES BETWEEN TANDEM REPEATS OF THE LUCIFERASE GENES IN SEVEN DINOFLAGELLATE SPECIES1 Liyun Liu and J. Woodland Hastings2 Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Harvard University, 16 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA Tandemly arranged luciferase genes were previ- Our previous studies of the structure of dinoflagel- ously reported in two dinoflagellates species, but lates genes and their circadian regulation revealed that their intergenic regions were strikingly different several occur in tandemly arranged copies (Le et al. and no canonical promoter sequences were found. 1997, Li and Hastings 1998, Okamoto et al. 2001). Here, we examined the intergenic regions of the Other than for ribosomal genes (Sollner-Webb and luciferase genes of five other dinoflagellate species Tower 1986) and a few protein-coding genes in two along with those of the earlier two. In all cases, the protozoa, Trypanosoma brucei and Babesia bovis (Lee and genes exist in multiple copies and are arranged Van der Ploeg 1997, Suarez et al. 1998), such an ar- tandemly, coding for proteins of similar sizes and rangement is not known in other eukaryotes. Indeed, sequences. However, the 50 untranslated region, 30 it is well known that the dinoflagellate nucleus is very untranslated region, and intergenic regions of the unusual; its envelope remains intact throughout the seven genes differ greatly in length and sequence, cell cycle, with the separation of the chromosomes in except for two stretches that are conserved in the mitosis being carried out by an external mitotic spindle intergenic regions of two pairs of phylogenetically (Taylor 1987). -

A MOLECULAR PHYLOGENY of MALARIAL PARASITES RECOVERED from CYTOCHROME B GENE SEQUENCES

J. Parasitol., 88(5), 2002, pp. 972±978 q American Society of Parasitologists 2002 A MOLECULAR PHYLOGENY OF MALARIAL PARASITES RECOVERED FROM CYTOCHROME b GENE SEQUENCES Susan L. Perkins* and Jos. J. Schall Department of Biology, University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont 05405. e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: A phylogeny of haemosporidian parasites (phylum Apicomplexa, family Plasmodiidae) was recovered using mito- chondrial cytochrome b gene sequences from 52 species in 4 genera (Plasmodium, Hepatocystis, Haemoproteus, and Leucocy- tozoon), including parasite species infecting mammals, birds, and reptiles from over a wide geographic range. Leucocytozoon species emerged as an appropriate out-group for the other malarial parasites. Both parsimony and maximum-likelihood analyses produced similar phylogenetic trees. Life-history traits and parasite morphology, traditionally used as taxonomic characters, are largely phylogenetically uninformative. The Plasmodium and Hepatocystis species of mammalian hosts form 1 well-supported clade, and the Plasmodium and Haemoproteus species of birds and lizards form a second. Within this second clade, the relation- ships between taxa are more complex. Although jackknife support is weak, the Plasmodium of birds may form 1 clade and the Haemoproteus of birds another clade, but the parasites of lizards fall into several clusters, suggesting a more ancient and complex evolutionary history. The parasites currently placed within the genus Haemoproteus may not be monophyletic. Plasmodium falciparum of humans was not derived from an avian malarial ancestor and, except for its close sister species, P. reichenowi,is only distantly related to haemospordian parasites of all other mammals. Plasmodium is paraphyletic with respect to 2 other genera of malarial parasites, Haemoproteus and Hepatocystis. -

Equine Piroplasmosis

EAZWV Transmissible Disease Fact Sheet Sheet No. 119 EQUINE PIROPLASMOSIS ANIMAL TRANS- CLINICAL SIGNS FATAL TREATMENT PREVENTION GROUP MISSION DISEASE ? & CONTROL AFFECTED Equines Tick-borne Acute, subacute Sometimes Babesiosis: In houses or chronic disease fatal, in Imidocarb Tick control characterised by particular in (Imizol, erythrolysis: fever, acute T.equi Carbesia, in zoos progressive infections. Forray) Tick control anaemia, icterus, When Dimenazene haemoglobinuria haemoglobinuria diaceturate (in advanced develops, (Berenil) stages). prognosis is Theileriosis: poor. Buparvaquone (Butalex) Fact sheet compiled by Last update J. Brandt, Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp, February 2009 Belgium Fact sheet reviewed by D. Geysen, Animal Health, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium F. Vercammen, Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp, Belgium Susceptible animal groups Horse (Equus caballus), donkey (Equus asinus), mule, zebra (Equus zebra) and Przewalski (Equus przewalskii), likely all Equus spp. are susceptible to equine piroplasmosis or biliary fever. Causative organism Babesia caballi: belonging to the phylum of the Apicomplexa, order Piroplasmida, family Babesiidae; Theileria equi, formerly known as Babesia equi or Nutallia equi, apicomplexa, order Piroplasmida, family Theileriidae. Babesia canis has been demonstrated by molecular diagnosis in apparently asymptomatic horses. A single case of Babesia bovis and two cases of Babesia bigemina have been detected in horses by a quantitative PCR. Zoonotic potential Equine piroplasmoses are specific for Equus spp. yet there are some reports of T.equi in asymptomatic dogs. Distribution Widespread: B.caballi occurs in southern Europe, Russia, Asia, Africa, South and Central America and the southern states of the US. T.equi has a more extended geographical distribution and even in tropical regions it occurs more frequent than B.caballi, also in the Mediterranean basin, Switzerland and the SW of France. -

First Case of Autochthonous Equine Theileriosis in Austria

pathogens Case Report First Case of Autochthonous Equine Theileriosis in Austria Esther Dirks 1, Phebe de Heus 1, Anja Joachim 2, Jessika-M. V. Cavalleri 1 , Ilse Schwendenwein 3, Maria Melchert 4 and Hans-Peter Fuehrer 2,* 1 Clinical Unit of Equine Internal Medicine, Department Hospital for Companion Animals and Horses, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, 1210 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] (E.D.); [email protected] (P.d.H.); [email protected] (J.-M.V.C.) 2 Department of Pathobiology, Institute of Parasitology, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, 1210 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] 3 Clinical Pathology Platform, Department of Pathobiology, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, 1210 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] 4 Centre for Insemination and Embryo transfer Platform, Department Hospital for Companion Animals and Horses, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, 1210 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +43-125-077-2205 Abstract: A 23-year-old pregnant warmblood mare from Güssing, Eastern Austria, presented with apathy, anemia, fever, tachycardia and tachypnoea, and a severely elevated serum amyloid A concentration. The horse had a poor body condition and showed thoracic and pericardial effusions, and later dependent edema and icteric mucous membranes. Blood smear and molecular analyses revealed an infection with Theileria equi. Upon treatment with imidocarb diproprionate, the mare improved clinically, parasites were undetectable in blood smears, and 19 days after hospitalization the horse was discharged from hospital. However, 89 days after first hospitalization, the mare again presented to the hospital with an abortion, and the spleen of the aborted fetus was also PCR-positive Citation: Dirks, E.; de Heus, P.; for T. -

Cytauxzoon Sp.: Un Protozoo Emergente Nel Gatto

Sede amministrativa: Università degli studi di Padova Dipartimento di Biomedicina Comparata e Alimentazione Scuola di Dottorato di ricerca in SCIENZE VETERINARIE Indirizzo: SCIENZE BIOMEDICHE VETERINARIE E COMPARATE Ciclo XXV CYTAUXZOON SP.: UN PROTOZOO EMERGENTE NEL GATTO Direttore della Scuola: Ch.mo Prof. Gianfranco Gabai Coordinatore di Indirizzo: Ch.mo Prof. Gianfranco Gabai Supervisore: Ch.mo Prof. Mario Pietrobelli Correlatori: Ch. ma Prof.ssa Gioia Capelli Dr. Tommaso Furlanello Dr.ssa Laia Solano-Gallego Dottoranda: Dr.ssa Erika Carli Alla mia famiglia e a chi se ne sente parte 2 Ringraziamenti L’ultima cosa che sto scrivendo in questa tesi è la prima che voglio sia letta e cioè questa pagina di ringraziamenti. Innanzitutto voglio ringraziare l’inventore del microscopio ottico, anche se non si sa chi sia. Galileo Galilei, uno dei possibili nomi, definì il microscopio di sua costruzione “un occhialino per vedere le cose minime”. Chi come me lavora quotidiamente con questo strumento, sa quanto sia affascinante e, a volte, esaltante poter vedere “le cose minime” e può capire quanto sia stato entusiasmante il momento in cui ho visto per la prima volta Cytauxzoon nei globuli rossi di un gatto! Incomincio con il ringraziare Marco Caldin che mi ha insegnato e trasmesso la sua passione per l’Ematologia. Lo ringrazio anche perché la Clinica San Marco, da lui diretta, ha totalmente finaziato questo progetto di ricerca. Ringrazio Mario Pietrobelli che mi ha seguita e accompagnata da buon tutor in questo percorso e che ha accolto sempre con grande entusiasmo gli annunci delle mie gravidanze. Grazie anche ai miei correlatori Tommaso Furlanello e Gioia Capelli, per avermi dato suggerimenti preziosi e spunti di riflessione. -

Pursuing Effective Vaccines Against Cattle Diseases Caused by Apicomplexan Protozoa

CAB Reviews 2021 16, No. 024 Pursuing effective vaccines against cattle diseases caused by apicomplexan protozoa Monica Florin-Christensen1,2, Leonhard Schnittger1,2, Reginaldo G. Bastos3, Vignesh A. Rathinasamy4, Brian M. Cooke4, Heba F. Alzan3,5 and Carlos E. Suarez3,6,* Address: 1Instituto de Patobiologia Veterinaria, Centro de Investigaciones en Ciencias Veterinarias y Agronomicas (CICVyA), Instituto Nacional de Tecnologia Agropecuaria (INTA), Hurlingham 1686, Argentina. 2Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientificas y Tecnologicas (CONICET), C1425FQB Buenos Aires, Argentina. 3Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Pathology, Washington State University, P.O. Box 647040, Pullman, WA, 991664-7040, United States. 4Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine, James Cook University, Cairns, Queensland, 4870, Australia. 5Parasitology and Animal Diseases Department, National Research Center, Giza, 12622, Egypt. 6Animal Disease Research Unit, Agricultural Research Service, USDA, WSU, P.O. Box 646630, Pullman, WA, 99164-6630, United States. ORCID information: Monica Florin-Christensen (orcid: 0000-0003-0456-3970); Leonhard Schnittger (orcid: 0000-0003-3484-5370); Reginaldo G. Bastos (orcid: 0000-0002-1457-2160); Vignesh A. Rathinasamy (orcid: 0000-0002-4032-3424); Brian M. Cooke (orcid: ); Heba F. Alzan (orcid: 0000-0002-0260-7813); Carlos E. Suarez (orcid: 0000-0001-6112-2931) *Correspondence: Carlos E. Suarez. Email: [email protected] Received: 22 November 2020 Accepted: 16 February 2021 doi: 10.1079/PAVSNNR202116024 The electronic version of this article is the definitive one. It is located here: http://www.cabi.org/cabreviews © The Author(s) 2021. This article is published under a Creative Commons attribution 4.0 International License (cc by 4.0) (Online ISSN 1749-8848). Abstract Apicomplexan parasites are responsible for important livestock diseases that affect the production of much needed protein resources, and those transmissible to humans pose a public health risk.