Equine Piroplasmosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Complexity of Piroplasms Life Cycles Marie Jalovecka, Ondrej Hajdusek, Daniel Sojka, Petr Kopacek, Laurence Malandrin

The complexity of piroplasms life cycles Marie Jalovecka, Ondrej Hajdusek, Daniel Sojka, Petr Kopacek, Laurence Malandrin To cite this version: Marie Jalovecka, Ondrej Hajdusek, Daniel Sojka, Petr Kopacek, Laurence Malandrin. The complexity of piroplasms life cycles. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, Frontiers, 2018, 8, pp.1-12. 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00248. hal-02628847 HAL Id: hal-02628847 https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02628847 Submitted on 27 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License REVIEW published: 23 July 2018 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00248 The Complexity of Piroplasms Life Cycles Marie Jalovecka 1,2,3*, Ondrej Hajdusek 2, Daniel Sojka 2, Petr Kopacek 2 and Laurence Malandrin 1 1 BIOEPAR, INRA, Oniris, Université Bretagne Loire, Nantes, France, 2 Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Ceskéˇ Budejovice,ˇ Czechia, 3 Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Ceskéˇ Budejovice,ˇ Czechia Although apicomplexan parasites of the group Piroplasmida represent commonly identified global risks to both animals and humans, detailed knowledge of their life cycles is surprisingly limited. -

Babesia Species

Laboratory diagnosis of babesiosis Babesia species Basic guidelines A. Capillary blood should be obtained by fingerstick, or venous blood should be obtained by venipuncture. B. Blood smears, at least two thick and two thin, should be prepared as soon as possible after col- lection. Delay in preparation of the smears can result in changes in parasite morphology and staining characteristics. In Babesia infections, infected red blood cells (rbcs) are normal in size. Typically rings are seen, and they may be vacuolated, pleomorphic or pyriform. Extracellular or tetrad-forms may also be present. Unlike Plasmodium spp., Babesia organisms lack pigment. Rings Rings of Babesia spp. have delicate cytoplasm and are often pleomorphic. Infected rbcs are not enlarged; multiple infection of rbcs can be common. Rings are usually vacuolated and do not produce pigment. Oc- casional classic tetrad-forms (Maltese Cross) or extracellular rings can be present. Rings of Babesia sp. in thick blood smears. Thin, delicate rings of Babesia sp. in a Babesia sp. in a thin blood smear, Thin blood smear showing a cluster of thin blood smear. showing pleomorphic rings and multiply- extracellular rings. infected rbcs. Laboratory diagnosis of babesiosis Babesia species Babesia microti in a thin blood smear. Note Babesia microti in thin blood smears. Notice the vacuolated and pleomorphic rings and multi- the classic “Maltese Cross” tetrad-form in ply-infected rbcs. Notice also there is no pigment present in any of the parasites. the infected rbc in the lower part of the image. Babesia sp. in a thin blood smear stained with Giemsa, showing pleomorphic rings and Babesia sp. -

And Toxoplasmosis in Jackass Penguins in South Africa

IMMUNOLOGICAL SURVEY OF BABESIOSIS (BABESIA PEIRCEI) AND TOXOPLASMOSIS IN JACKASS PENGUINS IN SOUTH AFRICA GRACZYK T.K.', B1~OSSY J.].", SA DERS M.L. ', D UBEY J.P.···, PLOS A .. ••• & STOSKOPF M. K .. •••• Sununary : ReSlIlIle: E x-I1V\c n oN l~ lIrIUSATION D'Ar\'"TIGENE DE B ;IB£,'lA PH/Re El EN ELISA ET simoNi,cATIVlTli t'OUR 7 bxo l'l.ASMA GONIJfI DE SI'I-IENICUS was extracted from nucleated erythrocytes Babesia peircei of IJEMIiNSUS EN ArRIQUE D U SUD naturally infected Jackass penguin (Spheniscus demersus) from South Africo (SA). Babesia peircei glycoprotein·enriched fractions Babesia peircei a ele extra it d 'erythrocytes nue/fies p,ovenanl de Sphenicus demersus originoires d 'Afrique du Sud infectes were obto ined by conca navalin A-Sepharose affinity column natulellement. Des fractions de Babesia peircei enrichies en chromatogrophy and separated by sod ium dodecyl sulphate glycoproleines onl ele oblenues par chromatographie sur colonne polyacrylam ide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE ). At least d 'alfinite concona valine A-Sephorose et separees par 14 protein bonds (9, 11, 13, 20, 22, 23, 24, 43, 62, 90, electrophorese en gel de polyacrylamide-dodecylsuJfale de sodium 120, 204, and 205 kDa) were observed, with the major protein (SOS'PAGE) Q uotorze bandes proleiques au minimum ont ete at 25 kDa. Blood samples of 191 adult S. demersus were tes ted observees (9, 1 I, 13, 20, 22, 23, 24, 43, 62, 90, 120, 204, by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assoy (ELISA) utilizing B. peircei et 205 Wa), 10 proleine ma;eure elant de 25 Wo. -

Development of a Polymerase Chain Reaction Method for Diagnosing Babesia Gibsoni Infection in Dogs

FULL PAPER Parasitology Development of a Polymerase Chain Reaction Method for Diagnosing Babesia gibsoni Infection in Dogs Shinya FUKUMOTO1), Xuenan XUAN1), Shinya SHIGENO2), Elikira KIMBITA1), Ikuo IGARASHI1), Hideyuki NAGASAWA1), Kozo FUJISAKI1) and Takeshi MIKAMI1) 1)National Research Center for Protozoan Diseases, Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Inada-cho, Obihiro, Hokkaido 080–8555 and 2)Leo Animal Hospital, 9 Yoriai-cho, Wakayama 640–8214, Japan (Received 16 January 2001/Accepted 17 May 2001) ABSTRACT. A pair of oligonucleotide primers were designed according to the nucleotide sequence of the P18 gene of Babesia gibsoni (B. gibsoni), NRCPD strain, and were used to detect parasite DNA from blood samples of B. gibsoni-infected dogs by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR was specific for B. gibsoni since no amplification was detected with DNA from B. canis or normal dog leucocytes. PCR was sensitive enough to detect parasite DNA from 2.5 µl of blood samples with a parasitemia of 0.000002%. PCR detected parasite DNA from 2 to 222 days post-infection in sequential blood samples derived from a dog experimentally infected with B. gibsoni. The detection of B. gibsoni DNA by PCR was much earlier than the detection of antibodies to B. gibsoni in blood samples by the indirect fluorescent antibody test (IFAT) or that of the parasite itself in Giemsa-stained thin blood smear film examined by microscopy. In addi- tion, 28 field samples collected from dogs in Kansai area, Japan, were tested for B. gibsoni infection. Nine samples were positive in blood smears, 9 samples were positive by IFAT and 11 samples were positive for B. -

Babesia Infection in Dogs

THE PET HEALTH LIBRARY By Wendy C. Brooks, DVM, DipABVP Educational Director, VeterinaryPartner.com Babesia Infection in Dogs Most people have never heard of Babesia organisms though they have caused red blood cell destruction in their canine hosts all over the world. Babesia organisms are spread by ticks and are of particular significance to racing greyhounds and pit bull terriers. Humans may also become infected. There are over 100 species of Babesia but only a few are found in the U.S. and are transmissible to dogs. Babesia canis, the “large” species of Babesia is one; Babesia gibsoni, a smaller Babesia that affects pit bull Babesia organism inside terriers almost exclusively is another; and a second but unnamed a red blood cell small Babesia has been identified in California. Babesia species continue to be classified and sub-classified worldwide. How Infection Happens and what Happens Next Infection occurs when a Babesia-infected tick bites a dog and releases Babesia sporozoites into the dog’s bloodstream. A tick must feed for two to three days to infect a dog withBabesia. The young Babesia organisms attach to red blood cells, eventually penetrating and making a new home within the cells for themselves. Inside the red blood cell, theBabesia organism divests its outer coating and begins to divide, becoming a new form called a merozoite that a new tick may ingest during a blood meal. Infected pregnant dogs can spread Babesia to their unborn puppies, and dogs can transmit the organism by biting another dog as well. (In fact, for Babesia gibsoni, which is primarily a pit bull terrier infection, ticks are a minor cause of infection and maternal transmission and bite wounds are the chief routes of transmission.) Having a parasite in your red blood cells does not go undetected by your immune system. -

Essential Function of the Alveolin Network in the Subpellicular

RESEARCH ARTICLE Essential function of the alveolin network in the subpellicular microtubules and conoid assembly in Toxoplasma gondii Nicolo` Tosetti1, Nicolas Dos Santos Pacheco1, Eloı¨se Bertiaux2, Bohumil Maco1, Lore` ne Bournonville2, Virginie Hamel2, Paul Guichard2, Dominique Soldati-Favre1* 1Department of Microbiology and Molecular Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland; 2Department of Cell Biology, Sciences III, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland Abstract The coccidian subgroup of Apicomplexa possesses an apical complex harboring a conoid, made of unique tubulin polymer fibers. This enigmatic organelle extrudes in extracellular invasive parasites and is associated to the apical polar ring (APR). The APR serves as microtubule- organizing center for the 22 subpellicular microtubules (SPMTs) that are linked to a patchwork of flattened vesicles, via an intricate network composed of alveolins. Here, we capitalize on ultrastructure expansion microscopy (U-ExM) to localize the Toxoplasma gondii Apical Cap protein 9 (AC9) and its partner AC10, identified by BioID, to the alveolin network and intercalated between the SPMTs. Parasites conditionally depleted in AC9 or AC10 replicate normally but are defective in microneme secretion and fail to invade and egress from infected cells. Electron microscopy revealed that the mature parasite mutants are conoidless, while U-ExM highlighted the disorganization of the SPMTs which likely results in the catastrophic loss of APR and conoid. Introduction *For correspondence: Toxoplasma gondii belongs to the phylum of Apicomplexa that groups numerous parasitic protozo- Dominique.Soldati-Favre@unige. ans causing severe diseases in humans and animals. As part of the superphylum of Alveolata, the ch Apicomplexa are characterized by the presence of the alveoli, which consist in small flattened single- membrane sacs, underlying the plasma membrane (PM) to form the inner membrane complex (IMC) Competing interest: See of the parasite. -

A Comparative Genomic Study of Attenuated and Virulent Strains of Babesia Bigemina

pathogens Communication A Comparative Genomic Study of Attenuated and Virulent Strains of Babesia bigemina Bernardo Sachman-Ruiz 1 , Luis Lozano 2, José J. Lira 1, Grecia Martínez 1 , Carmen Rojas 1 , J. Antonio Álvarez 1 and Julio V. Figueroa 1,* 1 CENID-Salud Animal e Inocuidad, Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias, Jiutepec, Morelos 62550, Mexico; [email protected] (B.S.-R.); [email protected] (J.J.L.); [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (C.R.); [email protected] (J.A.Á.) 2 Centro de Ciencias Genómicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, AP565-A Cuernavaca, Morelos 62210, Mexico; [email protected] * Correspondence: fi[email protected]; Tel.: +52-777-320-5544 Abstract: Cattle babesiosis is a socio-economically important tick-borne disease caused by Apicom- plexa protozoa of the genus Babesia that are obligate intraerythrocytic parasites. The pathogenicity of Babesia parasites for cattle is determined by the interaction with the host immune system and the presence of the parasite’s virulence genes. A Babesia bigemina strain that has been maintained under a microaerophilic stationary phase in in vitro culture conditions for several years in the laboratory lost virulence for the bovine host and the capacity for being transmitted by the tick vector. In this study, we compared the virulome of the in vitro culture attenuated Babesia bigemina strain (S) and the virulent tick transmitted parental Mexican B. bigemina strain (M). Preliminary results obtained by using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) showed that out of 27 virulence genes described Citation: Sachman-Ruiz, B.; Lozano, and analyzed in the B. -

(Alveolata) As Inferred from Hsp90 and Actin Phylogenies1

J. Phycol. 40, 341–350 (2004) r 2004 Phycological Society of America DOI: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2004.03129.x EARLY EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY OF DINOFLAGELLATES AND APICOMPLEXANS (ALVEOLATA) AS INFERRED FROM HSP90 AND ACTIN PHYLOGENIES1 Brian S. Leander2 and Patrick J. Keeling Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, Program in Evolutionary Biology, Departments of Botany and Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Three extremely diverse groups of unicellular The Alveolata is one of the most biologically diverse eukaryotes comprise the Alveolata: ciliates, dino- supergroups of eukaryotic microorganisms, consisting flagellates, and apicomplexans. The vast phenotypic of ciliates, dinoflagellates, apicomplexans, and several distances between the three groups along with the minor lineages. Although molecular phylogenies un- enigmatic distribution of plastids and the economic equivocally support the monophyly of alveolates, and medical importance of several representative members of the group share only a few derived species (e.g. Plasmodium, Toxoplasma, Perkinsus, and morphological features, such as distinctive patterns of Pfiesteria) have stimulated a great deal of specula- cortical vesicles (syn. alveoli or amphiesmal vesicles) tion on the early evolutionary history of alveolates. subtending the plasma membrane and presumptive A robust phylogenetic framework for alveolate pinocytotic structures, called ‘‘micropores’’ (Cavalier- diversity will provide the context necessary for Smith 1993, Siddall et al. 1997, Patterson -

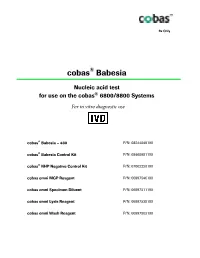

Package Insert

Rx Only ® cobas Babesia Nucleic acid test ® for use on the cobas 6800/8800 Systems For in vitro diagnostic use ® cobas Babesia – 480 P/N: 08244049190 cobas® Babesia Control Kit P/N: 08460981190 cobas® NHP Negative Control Kit P/N: 07002220190 cobas omni MGP Reagent P/N: 06997546190 cobas omni Specimen Diluent P/N: 06997511190 cobas omni Lysis Reagent P/N: 06997538190 cobas omni Wash Reagent P/N: 06997503190 cobas® Babesia Table of contents Intended use ............................................................................................................................ 4 Summary and explanation of the test ................................................................................. 4 Reagents and materials ......................................................................................................... 7 cobas® Babesia reagents and controls ....................................................................................................... 7 cobas omni reagents for sample preparation ........................................................................................ 10 Reagent storage and handling requirements ......................................................................................... 11 Additional materials required ................................................................................................................. 12 Instrumentation and software required ................................................................................................. 12 Precautions and handling requirements -

Phylogeny and Evolution of Theileria and Babesia Parasites in Selected Wild Herbivores of Kenya

PHYLOGENY AND EVOLUTION OF THEILERIA AND BABESIA PARASITES IN SELECTED WILD HERBIVORES OF KENYA LUCY WAMUYU WAHOME MASTER OF SCIENCE (Bioinformatics and Molecular Biology) JOMO KENYATTA UNIVERSITY OF AGRICULTURE AND TECHNOLOGY 2016 Phylogeny and Evolution of Theileria and Babesia Parasites in Selected Wild Herbivores of Kenya Lucy Wamuyu Wahome A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Science in Bioinformatics and Molecular Biology in the Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology. 2016 DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University. Signature………………………. Date…………………………… Wahome Lucy Wamuyu This thesis has been submitted for examination with our approval as university supervisors. Signature……………………… Date…………………………… Prof. Daniel Kariuki JKUAT, Kenya Signature……………………… Date…………………………… Dr.Sheila Ommeh JKUAT, Kenya Signature……………………… Date………………………… Dr. Francis Gakuya Kenya Wildlife Service, Kenya ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my beloved parents Mr. Godfrey, Mrs. Naomi and my only beloved sister Caroline for their tireless support throughout my academic journey. "I can do everything through Christ who gives me strength." iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Foremost I would like to acknowledge and thank the Almighty God for blessing, protecting and guiding me throughout this period. I am most grateful to the department of Biochemistry, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, for according me the opportunity to pursue my postgraduate studies. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors Prof. Daniel Kariuki, Dr. Sheila Ommeh and Dr. Francis Gakuya for the useful comments, remarks and engagement through out this project. My deepest gratitude goes to Dr. -

Wildlife Parasitology in Australia: Past, Present and Future

CSIRO PUBLISHING Australian Journal of Zoology, 2018, 66, 286–305 Review https://doi.org/10.1071/ZO19017 Wildlife parasitology in Australia: past, present and future David M. Spratt A,C and Ian Beveridge B AAustralian National Wildlife Collection, National Research Collections Australia, CSIRO, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. BVeterinary Clinical Centre, Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences, University of Melbourne, Werribee, Vic. 3030, Australia. CCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Wildlife parasitology is a highly diverse area of research encompassing many fields including taxonomy, ecology, pathology and epidemiology, and with participants from extremely disparate scientific fields. In addition, the organisms studied are highly dissimilar, ranging from platyhelminths, nematodes and acanthocephalans to insects, arachnids, crustaceans and protists. This review of the parasites of wildlife in Australia highlights the advances made to date, focussing on the work, interests and major findings of researchers over the years and identifies current significant gaps that exist in our understanding. The review is divided into three sections covering protist, helminth and arthropod parasites. The challenge to document the diversity of parasites in Australia continues at a traditional level but the advent of molecular methods has heightened the significance of this issue. Modern methods are providing an avenue for major advances in documenting and restructuring the phylogeny of protistan parasites in particular, while facilitating the recognition of species complexes in helminth taxa previously defined by traditional morphological methods. The life cycles, ecology and general biology of most parasites of wildlife in Australia are extremely poorly understood. While the phylogenetic origins of the Australian vertebrate fauna are complex, so too are the likely origins of their parasites, which do not necessarily mirror those of their hosts. -

Extra-Intestinal Coccidians Plasmodium Species Distribution Of

Extra-intestinal coccidians Apicomplexa Coccidia Gregarinea Piroplasmida Eimeriida Haemosporida -Eimeriidae -Theileriidae -Haemosporiidae -Cryptosporidiidae - Babesiidae (Plasmodium) -Sarcocystidae (Sacrocystis) Aconoid (Toxoplasmsa) Plasmodium species Causitive agent of Malaria ~155 species named Infect birds, reptiles, rodents, primates, humans Species is specific for host and •P. falciparum vector •P. vivax 4 species cause human disease •P. malariae No zoonoses or animal reservoirs •P. ovale Transmission by Anopheles mosquito Distribution of Malarial Parasites P. vivax most widespread, found in most endemic areas including some temperate zones P. falciparum primarily tropics and subtropics P. malariae similar range as P. falciparum, but less common and patchy distribution P. ovale occurs primarily in tropical west Africa 1 Distribution of Malaria US Army, 1943 300 - 500 million cases per year 1.5 to 2.0 million deaths per year #1 cause of infant mortality in Africa! 40% of world’s population is at risk Malaria Atlas Map Project http://www.map.ox.ac.uk/index.htm 2 Malaria in the United States Malaria was quite prevalent in the rural South It was eradicated after world war II in an aggressive campaign using, treatment, vector control and exposure control Time magazine - 1947 (along with overall improvement of living Was a widely available, conditions) cheap insecticide This was the CDCs initial DDT resistance misssion Half-life in mammals - 8 years! US banned use of DDT in 1973 History of Malaria Considered to be the most