Pursuing Effective Vaccines Against Cattle Diseases Caused by Apicomplexan Protozoa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Nh Dhhs Health Alert

THIS IS AN OFFICIAL NH DHHS HEALTH ALERT Distributed by the NH Health Alert Network [email protected] May 18, 2018, 1300 EDT (1:00 PM EDT) NH-HAN 20180518 Tickborne Diseases in New Hampshire Key Points and Recommendations: 1. Blacklegged ticks transmit at least five different infections in New Hampshire (NH): Lyme disease, Anaplasma, Babesia, Powassan virus, and Borrelia miyamotoi. 2. NH has one of the highest rates of Lyme disease in the nation, and 50-60% of blacklegged ticks sampled from across NH have been found to be infected with Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. 3. NH has experienced a significant increase in human cases of anaplasmosis, with cases more than doubling from 2016 to 2017. The reason for the increase is unknown at this time. 4. The number of new cases of babesiosis also increased in 2017; because Babesia can be transmitted through blood transfusions in addition to tick bites, providers should ask patients with suspected babesiosis whether they have donated blood or received a blood transfusion. 5. Powassan is a newer tickborne disease which has been identified in three NH residents during past seasons in 2013, 2016 and 2017. While uncommon, Powassan can cause a debilitating neurological illness, so providers should maintain an index of suspicion for patients presenting with an unexplained meningoencephalitis. 6. Borrelia miyamotoi infection usually presents with a nonspecific febrile illness similar to other tickborne diseases like anaplasmosis, and has recently been identified in one NH resident. Tests for Lyme disease do not reliably detect Borrelia miyamotoi, so providers should consider specific testing for Borrelia miyamotoi (see Attachment 1) and other pathogens if testing for Lyme disease is negative but a tickborne disease is still suspected. -

Exploration of Laboratory Techniques Relating to Cryptosporidium Parvum Propagation, Life Cycle Observation, and Host Immune Responses to Infection

EXPLORATION OF LABORATORY TECHNIQUES RELATING TO CRYPTOSPORIDIUM PARVUM PROPAGATION, LIFE CYCLE OBSERVATION, AND HOST IMMUNE RESPONSES TO INFECTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Cheryl Marie Brown In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major Department: Veterinary and Microbiological Sciences February 2014 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title EXPLORATION OF LABORATORY TECHNIQUES RELATING TO CRYPTOSPORIDIUM PARVUM PROPAGATION, LIFE CYCLE OBSERVATION, AND HOST IMMUNE RESPONSES TO INFECTION By Cheryl Marie Brown The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Dr. Jane Schuh Chair Dr. John McEvoy Dr. Carrie Hammer Approved: 4-8-14 Dr. Charlene Wolf-Hall Date Department Chair ii ABSTRACT Cryptosporidium causes cryptosporidiosis, a self-limiting diarrheal disease in healthy people, but causes serious health issues for immunocompromised individuals. Cryptosporidiosis has been observed in humans since the early 1970s and continues to cause public health concerns. Cryptosporidium has a complicated life cycle making laboratory study challenging. This project explores several ways of studying Cryptosporidium parvum, with a goal of applying existing techniques to further understand this life cycle. Utilization of a neonatal mouse model demonstrated laser microdissection as a tool for studying host immune response to infeciton. A cell culture technique developed on FrameSlides™ enables laser microdissection of individual infected cells for further analysis. Finally, the hypothesis that the availability of cells to infect drives the switch from asexual to sexual parasite reproduction was tested by time-series infection. -

Babesia Species

Laboratory diagnosis of babesiosis Babesia species Basic guidelines A. Capillary blood should be obtained by fingerstick, or venous blood should be obtained by venipuncture. B. Blood smears, at least two thick and two thin, should be prepared as soon as possible after col- lection. Delay in preparation of the smears can result in changes in parasite morphology and staining characteristics. In Babesia infections, infected red blood cells (rbcs) are normal in size. Typically rings are seen, and they may be vacuolated, pleomorphic or pyriform. Extracellular or tetrad-forms may also be present. Unlike Plasmodium spp., Babesia organisms lack pigment. Rings Rings of Babesia spp. have delicate cytoplasm and are often pleomorphic. Infected rbcs are not enlarged; multiple infection of rbcs can be common. Rings are usually vacuolated and do not produce pigment. Oc- casional classic tetrad-forms (Maltese Cross) or extracellular rings can be present. Rings of Babesia sp. in thick blood smears. Thin, delicate rings of Babesia sp. in a Babesia sp. in a thin blood smear, Thin blood smear showing a cluster of thin blood smear. showing pleomorphic rings and multiply- extracellular rings. infected rbcs. Laboratory diagnosis of babesiosis Babesia species Babesia microti in a thin blood smear. Note Babesia microti in thin blood smears. Notice the vacuolated and pleomorphic rings and multi- the classic “Maltese Cross” tetrad-form in ply-infected rbcs. Notice also there is no pigment present in any of the parasites. the infected rbc in the lower part of the image. Babesia sp. in a thin blood smear stained with Giemsa, showing pleomorphic rings and Babesia sp. -

And Toxoplasmosis in Jackass Penguins in South Africa

IMMUNOLOGICAL SURVEY OF BABESIOSIS (BABESIA PEIRCEI) AND TOXOPLASMOSIS IN JACKASS PENGUINS IN SOUTH AFRICA GRACZYK T.K.', B1~OSSY J.].", SA DERS M.L. ', D UBEY J.P.···, PLOS A .. ••• & STOSKOPF M. K .. •••• Sununary : ReSlIlIle: E x-I1V\c n oN l~ lIrIUSATION D'Ar\'"TIGENE DE B ;IB£,'lA PH/Re El EN ELISA ET simoNi,cATIVlTli t'OUR 7 bxo l'l.ASMA GONIJfI DE SI'I-IENICUS was extracted from nucleated erythrocytes Babesia peircei of IJEMIiNSUS EN ArRIQUE D U SUD naturally infected Jackass penguin (Spheniscus demersus) from South Africo (SA). Babesia peircei glycoprotein·enriched fractions Babesia peircei a ele extra it d 'erythrocytes nue/fies p,ovenanl de Sphenicus demersus originoires d 'Afrique du Sud infectes were obto ined by conca navalin A-Sepharose affinity column natulellement. Des fractions de Babesia peircei enrichies en chromatogrophy and separated by sod ium dodecyl sulphate glycoproleines onl ele oblenues par chromatographie sur colonne polyacrylam ide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE ). At least d 'alfinite concona valine A-Sephorose et separees par 14 protein bonds (9, 11, 13, 20, 22, 23, 24, 43, 62, 90, electrophorese en gel de polyacrylamide-dodecylsuJfale de sodium 120, 204, and 205 kDa) were observed, with the major protein (SOS'PAGE) Q uotorze bandes proleiques au minimum ont ete at 25 kDa. Blood samples of 191 adult S. demersus were tes ted observees (9, 1 I, 13, 20, 22, 23, 24, 43, 62, 90, 120, 204, by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assoy (ELISA) utilizing B. peircei et 205 Wa), 10 proleine ma;eure elant de 25 Wo. -

E. Coli (STEC) FACT SHEET

Escherichia coli O157:H7 & SHIGA TOXIN PRODUCING E. coli (STEC) FACT SHEET Agent: Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 or other Shiga Toxin Producing E. coli E. coli serotypes producing Shiga toxins. All are • Positive Shiga toxin test (e.g., EIA) gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria that produce Shiga toxin(s). Diagnostic Testing: A. Culture Brief Description: An infection of variable severity 1. Specimen: feces characterized by diarrhea (often bloody) and abdomi- 2. Outfit: Stool culture nal cramps. The illness may be complicated by 3. Lab Form: Form 3416 hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), in which red 4. Lab Test Performed: Bacterial blood cells are destroyed and the kidneys fail. This is isolation and identification. Tests for particularly a problem in children <5 years of age Shiga toxin I and II. PFGE. and the elderly. In the United States, hemolytic 5. Lab: Georgia Public Health Labora- uremic syndrome is the principal cause of acute tory (GPHL) in Decatur, Bacteriol- kidney failure in children, and most cases of ogy hemolytic uremic syndrome are caused by E. coli O157:H7 or another STEC. Another complication is B. Antigen Typing thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). As- 1. Specimen: Pure culture ymptomatic infections may also occur. 2. Outfit: Culture referral 3. Laboratory Form 3410 Reservoir: Cattle and possibly deer. Humans may 4. Test performed: Flagella antigen also serve as a reservoir for person-to-person trans- typing mission. 5. Lab: GPHL in Decatur, Bacteriology Mode of Transmission: Ingestion of contaminated Case Classification: food (most often inadequately cooked ground beef) • Suspected: A case of postdiarrheal HUS or but also unpasteurized milk and fruit or vegetables TTP (see HUS case definition in the HUS contaminated with feces. -

A Comparative Genomic Study of Attenuated and Virulent Strains of Babesia Bigemina

pathogens Communication A Comparative Genomic Study of Attenuated and Virulent Strains of Babesia bigemina Bernardo Sachman-Ruiz 1 , Luis Lozano 2, José J. Lira 1, Grecia Martínez 1 , Carmen Rojas 1 , J. Antonio Álvarez 1 and Julio V. Figueroa 1,* 1 CENID-Salud Animal e Inocuidad, Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias, Jiutepec, Morelos 62550, Mexico; [email protected] (B.S.-R.); [email protected] (J.J.L.); [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (C.R.); [email protected] (J.A.Á.) 2 Centro de Ciencias Genómicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, AP565-A Cuernavaca, Morelos 62210, Mexico; [email protected] * Correspondence: fi[email protected]; Tel.: +52-777-320-5544 Abstract: Cattle babesiosis is a socio-economically important tick-borne disease caused by Apicom- plexa protozoa of the genus Babesia that are obligate intraerythrocytic parasites. The pathogenicity of Babesia parasites for cattle is determined by the interaction with the host immune system and the presence of the parasite’s virulence genes. A Babesia bigemina strain that has been maintained under a microaerophilic stationary phase in in vitro culture conditions for several years in the laboratory lost virulence for the bovine host and the capacity for being transmitted by the tick vector. In this study, we compared the virulome of the in vitro culture attenuated Babesia bigemina strain (S) and the virulent tick transmitted parental Mexican B. bigemina strain (M). Preliminary results obtained by using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) showed that out of 27 virulence genes described Citation: Sachman-Ruiz, B.; Lozano, and analyzed in the B. -

(Alveolata) As Inferred from Hsp90 and Actin Phylogenies1

J. Phycol. 40, 341–350 (2004) r 2004 Phycological Society of America DOI: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2004.03129.x EARLY EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY OF DINOFLAGELLATES AND APICOMPLEXANS (ALVEOLATA) AS INFERRED FROM HSP90 AND ACTIN PHYLOGENIES1 Brian S. Leander2 and Patrick J. Keeling Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, Program in Evolutionary Biology, Departments of Botany and Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Three extremely diverse groups of unicellular The Alveolata is one of the most biologically diverse eukaryotes comprise the Alveolata: ciliates, dino- supergroups of eukaryotic microorganisms, consisting flagellates, and apicomplexans. The vast phenotypic of ciliates, dinoflagellates, apicomplexans, and several distances between the three groups along with the minor lineages. Although molecular phylogenies un- enigmatic distribution of plastids and the economic equivocally support the monophyly of alveolates, and medical importance of several representative members of the group share only a few derived species (e.g. Plasmodium, Toxoplasma, Perkinsus, and morphological features, such as distinctive patterns of Pfiesteria) have stimulated a great deal of specula- cortical vesicles (syn. alveoli or amphiesmal vesicles) tion on the early evolutionary history of alveolates. subtending the plasma membrane and presumptive A robust phylogenetic framework for alveolate pinocytotic structures, called ‘‘micropores’’ (Cavalier- diversity will provide the context necessary for Smith 1993, Siddall et al. 1997, Patterson -

Package Insert

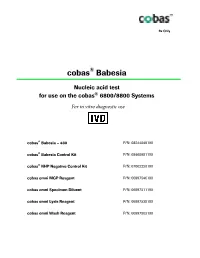

Rx Only ® cobas Babesia Nucleic acid test ® for use on the cobas 6800/8800 Systems For in vitro diagnostic use ® cobas Babesia – 480 P/N: 08244049190 cobas® Babesia Control Kit P/N: 08460981190 cobas® NHP Negative Control Kit P/N: 07002220190 cobas omni MGP Reagent P/N: 06997546190 cobas omni Specimen Diluent P/N: 06997511190 cobas omni Lysis Reagent P/N: 06997538190 cobas omni Wash Reagent P/N: 06997503190 cobas® Babesia Table of contents Intended use ............................................................................................................................ 4 Summary and explanation of the test ................................................................................. 4 Reagents and materials ......................................................................................................... 7 cobas® Babesia reagents and controls ....................................................................................................... 7 cobas omni reagents for sample preparation ........................................................................................ 10 Reagent storage and handling requirements ......................................................................................... 11 Additional materials required ................................................................................................................. 12 Instrumentation and software required ................................................................................................. 12 Precautions and handling requirements -

Cryptosporidiosis (Last Updated July 16, 2019; Last Reviewed July 16, 2019)

Cryptosporidiosis (Last updated July 16, 2019; last reviewed July 16, 2019) Epidemiology Cryptosporidiosis is caused by various species of the protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium, which infect the small bowel mucosa, and, if symptomatic, the infection typically causes diarrhea. Cryptosporidium can also infect other gastrointestinal and extraintestinal sites, especially in individuals whose immune systems are suppressed. Advanced immunosuppression—typically CD4 T lymphocyte cell (CD4) counts <100 cells/ mm3—is associated with the greatest risk for prolonged, severe, or extraintestinal cryptosporidiosis.1 The three species that most commonly infect humans are Cryptosporidium hominis, Cryptosporidium parvum, and Cryptosporidium meleagridis. Infections are usually caused by one species, but a mixed infection is possible.2,3 Cryptosporidiosis remains a common cause of chronic diarrhea in patients with AIDS in developing countries, with up to 74% of diarrheal stools from patients with AIDS demonstrating the organism.4 In developed countries with low rates of environmental contamination and widespread availability of potent antiretroviral therapy, the incidence of cryptosporidiosis has decreased. In the United States, the incidence of cryptosporidiosis in patients with HIV is now <1 case per 1,000 person-years.5 Infection occurs through ingestion of Cryptosporidium oocysts. Viable oocysts in feces can be transmitted directly through contact with humans or animals infected with Cryptosporidium, particularly those with diarrhea. Cryptosporidium oocysts can contaminate recreational water sources, such as swimming pools and lakes, and public water supplies and may persist despite standard chlorination. Person-to-person transmission of Cryptosporidium is common, especially among sexually active men who have sex with men. Clinical Manifestations Patients with cryptosporidiosis most commonly have acute or subacute onset of watery diarrhea, which may be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and lower abdominal cramping. -

Control of Intestinal Protozoa in Dogs and Cats

Control of Intestinal Protozoa 6 in Dogs and Cats ESCCAP Guideline 06 Second Edition – February 2018 1 ESCCAP Malvern Hills Science Park, Geraldine Road, Malvern, Worcestershire, WR14 3SZ, United Kingdom First Edition Published by ESCCAP in August 2011 Second Edition Published in February 2018 © ESCCAP 2018 All rights reserved This publication is made available subject to the condition that any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise is with the prior written permission of ESCCAP. This publication may only be distributed in the covers in which it is first published unless with the prior written permission of ESCCAP. A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN: 978-1-907259-53-1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 1: CONSIDERATION OF PET HEALTH AND LIFESTYLE FACTORS 5 2: LIFELONG CONTROL OF MAJOR INTESTINAL PROTOZOA 6 2.1 Giardia duodenalis 6 2.2 Feline Tritrichomonas foetus (syn. T. blagburni) 8 2.3 Cystoisospora (syn. Isospora) spp. 9 2.4 Cryptosporidium spp. 11 2.5 Toxoplasma gondii 12 2.6 Neospora caninum 14 2.7 Hammondia spp. 16 2.8 Sarcocystis spp. 17 3: ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL OF PARASITE TRANSMISSION 18 4: OWNER CONSIDERATIONS IN PREVENTING ZOONOTIC DISEASES 19 5: STAFF, PET OWNER AND COMMUNITY EDUCATION 19 APPENDIX 1 – BACKGROUND 20 APPENDIX 2 – GLOSSARY 21 FIGURES Figure 1: Toxoplasma gondii life cycle 12 Figure 2: Neospora caninum life cycle 14 TABLES Table 1: Characteristics of apicomplexan oocysts found in the faeces of dogs and cats 10 Control of Intestinal Protozoa 6 in Dogs and Cats ESCCAP Guideline 06 Second Edition – February 2018 3 INTRODUCTION A wide range of intestinal protozoa commonly infect dogs and cats throughout Europe; with a few exceptions there seem to be no limitations in geographical distribution. -

New Aspects of Human Trichinellosis: the Impact of New Trichinella Species F Bruschi, K D Murrell

15 REVIEW Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pmj.78.915.15 on 1 January 2002. Downloaded from New aspects of human trichinellosis: the impact of new Trichinella species F Bruschi, K D Murrell ............................................................................................................................. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:15–22 Trichinellosis is a re-emerging zoonosis and more on anti-inflammatory drugs and antihelminthics clinical awareness is needed. In particular, the such as mebendazole and albendazole; the use of these drugs is now aided by greater clinical description of new Trichinella species such as T papuae experience with trichinellosis associated with the and T murrelli and the occurrence of human cases increased number of outbreaks. caused by T pseudospiralis, until very recently thought to The description of new Trichinella species, such as T murrelli and T papuae, as well as the occur only in animals, requires changes in our handling occurrence of outbreaks caused by species not of clinical trichinellosis, because existing knowledge is previously recognised as infective for humans, based mostly on cases due to classical T spiralis such as T pseudospiralis, now render the clinical picture of trichinellosis potentially more compli- infection. The aim of the present review is to integrate cated. Clinicians and particularly infectious dis- the experiences derived from different outbreaks around ease specialists should consider the issues dis- the world, caused by different Trichinella species, in cussed in this review when making a diagnosis and choosing treatment. order to provide a more comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment. SYSTEMATICS .......................................................................... Trichinellosis results from infection by a parasitic nematode belonging to the genus trichinella. -

Epidemiology of Cryptosporidiosis in HIV-Infected Individuals

Iqbal et al., 1:9 http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/scientificreports.431 Open Access Open Access Scientific Reports Scientific Reports Review Article OpenOpen Access Access Epidemiology of Cryptosporidiosis in HIV-Infected Individuals: A Global Perspective Asma Iqbal1,2, Yvonne AL Lim1*, Mohammad AK Mahdy1, Brent R Dixon2 and Johari Surin2 1Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2Bureau of Microbial Hazards, Food Directorate, Health Canada, Banting Research Centre, 251 Sir Frederick Banting Driveway, P.L.2204E, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0K9 Canada Abstract Cryptosporidiosis, resulting from infection with the protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium, is a significant opportunistic disease among HIV-infected individuals. With multiple routes of infection due to the recalcitrant nature of its infectious stage in the environment, the formulation of effective and practical control strategies for cryptosporidiosis must be based on a firm understanding of its epidemiology. Prevalence data and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium in HIV-infected individuals is currently available from numerous countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, North America and South America, and it is clear that significant differences exist between developing and developed regions. This review highlights the current global status of Cryptosporidium infections among HIV-infected individuals, and puts forth a contextual framework for the development of integrated surveillance and control programs for cryptosporidiosis in immune compromised patients. Given that there are few specific chemotherapeutic agents available for cryptosporidiosis, and therapy is largely based on improving the patient’s immune status, the focus should be on patient compliance and non-compliance obstacles to the effective delivery of health care, as well as educating HIV-infected individuals in the prevention of infection.