Case Autazes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boletim Resumido - Vacinas COVID-19

Boletim resumido - vacinas COVID-19 Municípios Tudo População programada para Doses aplicadas (1º dose) População vacinada (%) - 1º dose ser contemplada por dose 174.990 Total de doses aplicadas 53,5% População vacinada (%) - 2º dose 327.311 Doses aplicadas (2º dose) 179.150 4.160 1,3% Remessa Tudo Total de doses disponíveis Doses distribuídas até a data Doses a serem entregues 555.044 548.600 6.444 Vacinômetro 0,0% 100,0% Trabalhadores de saúde População indígena aldeada 1º dose (58.099) 60,2% 96.579 1º dose 42.343 (42,1%) 100.642 2º dose (3.771) 3,9% 96.579 2º dose 223 (3,3%) 100.642 População >60 anos institucionalizada Pessoas institucinalizadas com deficiência 1º dose 1º dose 2º dose 2º dose Pessoas > 80 anos Pessoas com 75 - 79 anos 1º dose 2º dose Pessoas com 70 - 74 anos 1º dose 2º dose Nota: Atualizado em 11/02/2021 - Os municípios que eventualmente receberam doses excedentes do programada, são devolvidas para a rede estadual de imunização. - Observações: para download dos dados do painel clique na tabela, em seguida, clique no botão download do painel e selecione "Dados". Vacinômetro da 1º dose Vacinômetro da 2º dose (total de população programada vacinada e meta atingida - % ) (total de população programada vacinada e meta atingida - % ) Amazonas Amazonas Municípios Municípios Manaus Manaus São Gabriel da Cachoeira Humaitá Benjamin Constant Apuí Tabatinga Carauari Itacoatiara Tapauá Parintins Presidente Figueiredo Santo Antônio do Içá Atalaia do Norte Autazes Codajás Borba Novo Airão Maués Borba Tefé Japurá Manicoré Maraã Manacapuru -

LEI Nº 1828 De 30/12/1987

PODER LEGISLATIVO ASSEMBLEIA LEGISLATIVA DO ESTADO DO AMAZONAS LEI Nº 1828 de 30/12/1987 CRIA o Município do Careiro da Várzea, dispõe sobre sua sede. Art. 1º - Fica criado o Município do Careiro da Várzea, desmembrado do Município do Creiro, obedecendo os seguin-tes limites: I - Com o Município de Autazes: Começando na interseção da margem direita do Rio Amazonas com o meridiano da confluência do Rio Mutuca, no Paraná do Autaz-Mirim; este meridiano para sul, até alcançar a interseção de suas cabeceiras com a linha que limita os Municípios do Careiro/Autazes; II - Com o Município do Careiro: Começando na interseção da linha que limita só Municípios do Careiro/Autazes com a cabeceira do Rio Mutuca, daí pelo divisor de águas do Rio Mutuca e Paraná do Autaz-Mirim até o ponto confrontante da foz do Lago do Puru-Puru com o Paraná do Autaz-Mirim, seguindo pelo contraforte atá a referida confluência, dessa confluência seguindo pelo paraná do Autaz-Mirim até a foz do Lago do Salsa, desta foz pelo divisor de águas do Lago do Salsa com o paraná do Autaz-Mirim e divisor de águas do Lago do Puru-Puru com o Igarapé Jacuraru até sua interseção com o eixo da Ro-dovia BR-319 com o Ramal 22, no KM 22, esta Rodovia no sentido da cidade de Manaus, até sua interseção com o paraná do Autaz-Mirim, este paraná subindo por uma linha mediana, até sua confluência com a margem direita do paraná do Curari-Grande, desta confluência por uma linha no sentido sudoeste até encontrar a confluência do Igarapé do Barão com o Igarapé do Cacau, desta confluência por uma linha -

Aspectos Epidemiológicos E Clínicos Dos Acidentes Ofídicos Ocorridos Nos Municípios Do Estado Do Amazonas

Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical ARTIGO 32(6):637-646, nov-dez, 1999. Aspectos epidemiológicos e clínicos dos acidentes ofídicos ocorridos nos municípios do Estado do Amazonas Epidemiological and clinical aspects of snake accidentes in the municipalities of the State of Amazonas, Brazil Célio Campos Borges1, Megumi Sadahiro2 e Maria Cristina dos Santos3* Resumo No Amazonas, o acidente ofídico é um problema de saúde pública pouco conhecido. Por este motivo, foi realizado um estudo descritivo dos acidentes ofídicos atendidos nas Unidades de Saúde de 34 municípios, um distrito e dois pelotões de fronteira do Estado do Amazonas. As características mais comuns encontradas dentre os pacientes foram: agricultor (50,4%), do sexo masculino (81,3%), em idade produtiva (72,1%), picado no membro inferior (88,5%), por jararaca (48,6%) ou surucucu (46,8%), na zona rural de seu município (70,2%) e que só recebeu atendimento médico em tempo superior a seis horas, após acidente (57,3%). As manifestações locais mais freqüentes foram: edema (76,9%), dor (68,7%), eritema (10,2%) e hemorragia (9,3%). Hemorragia (18,8%) foi a manifestação sistêmica mais freqüente. O antiveneno foi administrado em apenas 65,9% dos pacientes. A via mais utilizada foi a endovenosa (52,3%), sendo relevante o uso de vias não mais recomendadas (47,7%). O antiveneno administrado, na maioria dos pacientes, foi o antibotrópico (66,7%). As complicações mais freqüentes foram abcesso (13,7%), necrose (12,3%), infecção secundária (8,3%), insuficiência renal (2,5%) e gangrena (2,5%). Os procedimentos médicos mais usados para o tratamento das complicações foram: drenagem (52,6%), debridamento (28,9%), amputação (10,5%), limpeza cirúrgica (5,3%) e diálise peritoneal (2,6%). -

26.784.3005.20Ln.0001

1 TRIBUNAL DE CONTAS DA UNIÃO Secretaria-Geral de Controle Externo Secretaria de Fiscalização de Infraestrutura Portuária e Ferroviária RELATÓRIO DE FISCALIZAÇÃO TC n. 021.011/2020-6 Fiscalização n. 115/2020 Relator: André de Carvalho DA FISCALIZAÇÃO Modalidade: Conformidade Ato originário: Acórdão 1.010/2020 - Plenário Objeto da fiscalização: Manutenção e operação de terminais hidroviários IP4 Funcional programática: 26.784.3005.20LN.0001/2020 - OPERAÇÃO DE TERMINAIS HIDROVIÁRIOS NACIONAL Tipo da Obra: Ferrovia Período abrangido pela fiscalização: De 02/12/2015 a 17/07/2020 DO ÓRGÃO/ENTIDADE FISCALIZADO Órgão/entidade fiscalizado: Departamento Nacional de Infraestrutura de Transportes Vinculação (ministério): Ministério da Infraestrutura Vinculação TCU (unidade técnica): Secretaria de Fiscalização de Infraestrutura Rodoviária e de Aviação Civil Responsável pelo órgão/entidade: nome: Antonio Leite dos Santos Filho cargo: Diretor-Geral do Departamento Nacional de Infraestrutura de Transportes - Dnit período: A partir de 14/01/2019 Outros responsáveis: vide peça: “Rol de responsáveis” 2 TRIBUNAL DE CONTAS DA UNIÃO Secretaria-Geral de Controle Externo Secretaria de Fiscalização de Infraestrutura Portuária e Ferroviária Resumo Em cumprimento ao Acórdão 1.010/2020-TCU-Plenário, Relator Ministro José Múcio Monteiro, realizou-se auditoria no Departamento Nacional de Infraestrutura de Transportes, no período compreendido entre 15/6/2020 e 31/7/2020, com o objetivo de fiscalizar contratações relacionadas à operação geral e à manutenção dos sistemas de amarração e fundeio de terminais hidroviários do tipo IP4. As razões que motivaram esta auditoria foram o grande vulto desses empreendimentos, cuja soma atinge R$ 203.055.535,02, nas datas bases setembro de 2014, julho de 2015 e dezembro de 2017, bem como a relevância de que os terminais hidroviários IP4 construídos na região norte estejam operacionais para a sociedade e tenham mitigados seus riscos de acidentes provocados pelo acúmulo de toras e galhadas nas suas estruturas de ancoragem. -

Saúde E Doença Entre Os Índios Mura De Autazes (Amazonas): Processos Socioculturais E a Práxis Da Auto-Atenção

Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina – UFSC Centro de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas – CFH Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia Social -PPGAS Saúde e Doença entre os Índios Mura de Autazes (Amazonas): processos socioculturais e a práxis da auto-atenção. Daniel Scopel Florianópolis, Março de 2007 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina – UFSC Centro de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas – CFH Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia Social -PPGAS Saúde e Doença entre os Índios Mura de Autazes (Amazonas): processos socioculturais e a práxis da auto-atenção. Daniel Scopel Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia Social da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Prof. Dr. Flavio Braune Wiik Orientador Prof. Dr.Oscar Calávia Sáez Co-Orientador Florianópolis, Março de 2007 Programa de Pós Graduação em Antropologia Social Saúde e Doença entre os Índios Mura de Autazes (Amazonas): processos socioculturais e a práxis da auto-atenção. Daniel Scopel Orientador: Dr. Flávio Braune Wiik Co-Orientador: Dr.Oscar Calávia Sáez Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia Social da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Antropologia Social, aprovada pela banca composta pelos seguintes professores. Prof. a Dra Eliana Diehl Componente da Banca Prof.a Dra. Esther Jean Langdon Componente da Banca Prof.a Dr. Alberto Groisman Componente da Banca (Suplente) Florianópolis, 16 de março de 2007. Dedicado à Raquel. iv Ilustração 1– Mura inalando Paricá – Prancha 121 da Viagem Filosófica de Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira (RAMINELLI, 2001) v AGRADECIMENTOS Um Mura provavelmente começaria este agradecimento assim: “-Primeiramente gostaria de agradecer a Deus, mas segundo à minha família.” Reconheço a sabedoria dessa forma de agradecer. -

Gerência De Epidemiologia Estrutura Organizacional E Recursos Humanos

Gerência de Epidemiologia Estrutura Organizacional e Recursos Humanos Dra. Lucilene Sales Arinilda Andreza Maria Débora Álvaro Roger Assis Raju Radiene Janete Moraes Diego Socorro Abreu AçõesAçõesAções realizadas realizadas realizadas nos nos MunicípiosMunicípios Municípios do do Amazonas do Amazonas Amazonas pela pela pelaFundaçãoFundação Fundação Alfredo Alfredo Alfredo da da MattaMatta da Matta 2016em 2014 2015 S. G. DA CACHOEIRA STA. I. DO R. NEGRO BARCELOS URUCARÁ PRES. FIGUEIREDO JAPURÁ S. S. UATUMÃ HNAMUNDÁ MARAA FONTE BOA NOVO AIRÃO ITAPIRANGA R. P. EVA PARINTINS MANAUS URUCURITUBA TONANTINS SILVES STO. A. IÇA CAAPIRANGA UARINI CODAJAS B. V. RAMOS IRAND. AMATURA MANACAPURU C. VÁRZEA ITACOATIARA JURUA CAREIRO BARRERINHA ALVARAES ANAMA CAREIRO AUTAZES N. O. NORTE TABATINGA TABATINGA MANAQUIRI COARI ANORI JUTAI TEFE BERURI S. P. OLIVENÇA BORBA MAUES CARAUARI BENJ. CONSTANT ATALAIA DO NORTE Intensificação + Monitoramento MANICORE N. ARIPUANÃ TAPAUA EIRUNEPE ITAMARATI Treinamento na FUAM IPIXUNA GUAJARA CANUTAMA HUMAITA Treinamento via Telessaúde PAUINI APUI ENVIRA Realizado Cirurgia LABREA BOCA DO ACRE 53 Municípios2540 Municípios supervisionados supervisionados Ações realizadas nos Municípios do Amazonas pela Fundação Alfredo da Matta 2014, 2015 e 2016 2014 2015 25 Municípios 40 Municipios S. G. DA CACHOEIRA STA. I. DO R. NEGROBARCELOS S. G. DA CACHOEIRA STA. I. DO R. NEGROBARCELOS URUCARÁ URUCARÁ PRES. FIGUEIREDO JAPURÁ PRES. FIGUEIREDO JAPURÁ S. S. UATUMÃHNAMUNDÁ S. S. UATUMÃ MARAA MARAA HNAMUNDÁ FONTE BOA NOVO AIRÃO ITAPIRANGA FONTE BOA NOVO AIRÃO ITAPIRANGA R. P. EVA PARINTINS R. P. EVA PARINTINS MANAUS MANAUS TONANTINS SILVESURUCURITUBA TONANTINS SILVESURUCURITUBA STO. A. IÇA STO. A. IÇA UARINI CODAJASCAAPIRANGA B. V. RAMOS UARINI CODAJASCAAPIRANGA B. V. RAMOS AMATURA MANACAPURUIRAND.C. -

Agricultura Familiar Na Costa Da Terra Nova

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO AMAZONAS FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS AGRÁRIAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS AGRÁRIAS ILZON CASTRO PINTO AGRICULTURA FAMILIAR NA COSTA DA TERRA NOVA Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação Agricultura e Sustentabilidade na Amazônia da Universidade Federal do Amazonas, como requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Agricultura e Sustentabilidade na Amazônia, na Área de Concentração de Sistemas Agroflorestais. Orientadora: Profª Drª Therezinha de Jesus Pinto Fraxe MANAUS 2005 Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. ii ILZON CASTRO PINTO AGRICULTURA FAMILIAR NA COSTA DA TERRA NOVA Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação Agricultura e Sustentabilidade na Amazônia da Universidade Federal do Amazonas, como requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Agricultura e Sustentabilidade na Amazônia, na Área de Concentração de Sistemas Agroflorestais. Aprovado em 30 de abril de 2005 BANCA EXAMINADORA Profa. Dra. Therezinha de Jesus Pinto Fraxe, Presidente Universidade Federal do Amazonas Prof. Dr. Carlos Moisés de Medeiros, Membro Universidade Federal do Amazonas Dr. Ricardo Lopes, Membro Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária iii Ao meu pai e minha mãe em memória, A minha esposa Marilena e ao meu filho Wilzon pelo incentivo e apoio para a realização deste trabalho. DEDICO iv AGRADECIMENTOS A Deus, por todas as coisas que nos tem propiciado durante esse trabalho. A minha professora e orientadora Therezinha de Jesus Pinto Fraxe, pelo apoio e ensinamentos transmitidos durante esta árdua mais profícua caminhada que alcançou o seu objetivo. A toda minha família que direta ou indiretamente tem contribuído para mais essa realização profissional; em especial a minhas irmãs Eliênnia, Raimunda e Maria. -

Genetic Diversity and Potential Paths of Transmission of Mycobacterium Bovis in the Amazon: the Discovery of M

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 16 February 2021 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.630989 Genetic Diversity and Potential Paths of Transmission of Mycobacterium bovis in the Amazon: The Discovery of M. bovis Lineage Lb1 Circulating in Edited by: Dirk Werling, South America Royal Veterinary College (RVC), United Kingdom Paulo Alex Carneiro 1,2, Cristina Kraemer Zimpel 3,4, Taynara Nunes Pasquatti 5, 3 6 6 Reviewed by: Taiana T. Silva-Pereira , Haruo Takatani , Christian B. D. G. Silva , 4 3 7 José Ángel Gutiérrez-Pabello, Robert B. Abramovitch , Ana Marcia Sa Guimaraes , Alberto M. R. Davila , 8 1 National Autonomous University of Flabio R. Araujo and John B. Kaneene * Mexico, Mexico 1 Lorraine Michelet, Center for Comparative Epidemiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, 2 3 Agence Nationale de Sécurité United States, Amazonas State Federal Institute, Manaus, Brazil, Laboratory of Applied Research in Mycobacteria, 4 Sanitaire de l’Alimentation, de Department of Microbiology, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, Department of 5 l’Environnement et du Travail Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States, Dom Bosco Catholic 6 7 (ANSES), France University, Campo Grande, Brazil, Agência de Defesa Agropecuaria Do Amazonas, Manaus, Brazil, Computational and Edgar Abadia, Systems Biology Laboratory, Oswaldo Cruz Institute and Graduate Program in Biodiversity and Health, FIOCRUZ, 8 Instituto Venezolano de Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Embrapa Gado de Corte, Campo Grande, Brazil Investigaciones Científicas (IVIC), Venezuela Bovine tuberculosis (bTB) has yet to be eradicated in Brazil. Herds of cattle and Sven David Parsons, Stellenbosch University, South Africa buffalo are important sources of revenue to people living in the banks of the Amazon *Correspondence: River basin. -

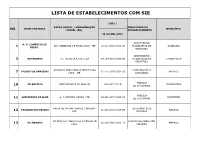

Lista De Estabelecimentos Com Sie

LISTA DE ESTABELECIMENTOS COM SIE CNPJ / RAZÃO SOCIAL / DENOMINAÇÃO FINALIDADE DO SIE NOME FANTASIA MUNICÍPIO SOCIAL (PR) ESTABELECIMENTO IE OU IPR (CPF) ABATEDOURO N. R. COMÉRCIO DE N R COMERCIO DE FRIOS LTDA - ME 19.921.602/ 0001-00 FRIGORÍFICO DE IRANDUBA 1 FRIOS. BOVIDEOS ABATEDOURO 3 BOVINORTE L L TEIXEIRA & CIA LTDA 04.764.429/ 0001-06 FRIGORÍFICO DE ITACOATIARA BOVIDEOS SANSSINI PRODUTOS ALIMENTICIOS ENTREPOSTO DE PRODUTOS SANSSINI 07.477.593/ 0001-20 MANAUS 7 LTDA - ME LATICÍNIOS FÁBRICA VÔ BATISTA JOSÉ ANTUNES DE ARAUJO 000.963.772-91 ITACOATIARA 10 DE LATICÍNIOS FÁBRICA LATICINIOS DA ILHA A. J. PRESTES VIEIRA - ME 04.848.627/ 0001-58 PARINTINS 11 DE LATICÍNIOS MARIA DE FATIMA CHAVES COIMBRA - ENTREPOSTO DE FRIGORIFICO PEIXAO 01.115.810/ 0001-56 MANAUS 12 EPP PESCADO DC MANAUS INDUSTRIA E COMÉRCIO FÁBRICA DE PRODUTOS DC MANAUS 03.102.780/ 0001-79 MANAUS 13 LTDA CÁRNEOS ENTREPOSTO DE FRUTAL ALIMENTOS FRUTAL INDUSTRIA E COMERCIO LTDA 05.646.631/ 0001-04 MANAUS 14 LATICÍNIOS FÁBRICA FRUTAL ALIMENTOS FRUTAL INDUSTRIA E COMERCIO LTDA 05.646.631/ 0001-04 MANAUS 14 DE LATICÍNIOS FÁBRICA AMAZONGURT T.M.L. DA SILVA - ME 01.215.382/ 0001-33 MANAUS 17 DE LATICÍNIOS ABATEDOURO MANAOS COMÉRCIO DE CARNES E FRIGONOSSO 10.865.809/003-00 FRIGORÍFICO DE BOCA DO ACRE 18 CEREAIS LTDA. BOVIDEOS VITELLO - BOM ENTREPOSTO DE FRIGORIFICO VITELLO LTDA 84.125.681/ 0001-04 MANAUS 20 TEMPERO CARNE E DERIVADOS ENTREPOSTO DE FRUTAL ALIMENTOS FRUTAL INDUSTRIA E COMERCIO LTDA 05.646.631/ 0001-04 MANAUS 21 LATICÍNIOS ASSOCIAÇÃO DOS PRODUTORES DE FÁBRICA ASPROLEIP 05.068.288/ 0001-50 APUÍ 23 LEITE DE APUÍ DE LATICÍNIOS ENTREPOSTO DE NATUCARNE L.B. -

Relação De Contratos De Obras E Serviços De Engenharia - Sendo Tocadas Cópia Digital Dos N.º Contrato % Faturado Liquidado Saldo Contratual Item Mod

Secretaria de Infraestrutura e Região Metropolitana de Manaus RELAÇÃO DE CONTRATOS DE OBRAS E SERVIÇOS DE ENGENHARIA - SENDO TOCADAS CÓPIA DIGITAL DOS N.º CONTRATO % FATURADO LIQUIDADO SALDO CONTRATUAL ITEM MOD. DE LICITAÇÃO N.º EDITAL DESCRIÇÃO DO OBJETO MUNICÍPIO VALOR GLOBAL (a) PAGO TERMOS DO SEINFRA (E-OBRAS) (b) (a-b) CONTRATO CT - 054/2018 - Recuperação do sistema viário na sede do municipio de Termo de 1 CC- CONCORRÊNCIA 077/2018 Amaturá 2.874.238,96 78% 2.252.333,21 2.252.333,21 621.905,75 SEINFRA Amaturá contrato/aditivos CT - 050/2018 Recuperação do sistema viário na sede do município de Termo de 2 CC- CONCORRÊNCIA 044/2018 Anamã 5.875.844,57 96% 5.625.827,74 5.625.827,74 250.016,83 SEINFRA Anamã contrato/aditivos CT - 021/2019 - Ampliação da rede de abastecimento de água do Município de Termo de 3 CC- CONCORRÊNCIA 092/2018 Apuí 4.293.206,10 90% 3.874.806,88 3.874.806,88 418.399,22 SEINFRA Apuí contrato/aditivos CT - 065/2018 Implantação e recuperação de ramais no Município de Termo de 4 CC- CONCORRÊNCIA 083/2018 Autazes 42.852.072,07 100% 42.852.072,07 42.852.072,07 - SEINFRA Autazes Contrato/aditivos Serviços de recuperação do ramal Marechal Rondon (KM-91) CT - 021/2020 Termo de 5 CC- CONCORRÊNCIA 005/2020 e do ramal São Felix (KM-93) localizados na AM-254, no Autazes 9.910.334,35 0% - - 9.910.334,35 SEINFRA Município de Autazes/AM. contrato/aditivos Conservação e Manutenção Das Rodovias Estaduais do CT - 004/2020 - Termo de 6 CC- CONCORRÊNCIA 022/2019 Amazonas. -

MINISTÉRIO PÚBLICO DE CONTAS Coordenadoria De Transparência, Acesso À Informação E Controle Interno Procuradora Evelyn Freire De Carvalho

ESTADO DO AMAZONAS MINISTÉRIO PÚBLICO DE CONTAS Coordenadoria de Transparência, Acesso à Informação e Controle Interno Procuradora Evelyn Freire de Carvalho Ranking da Transparência das Prefeituras 0 20 40 60 80 100 Manaus 0 20 40 60 80 10087,45 ManausTefé 73,6487,45 Maués 63,1673,64 Maués 63,16 Rio Preto da Eva 53,9953,99 ApuíApuí 53,5153,51 Coari 53,1053,10 Iranduba 52,17 Iranduba 51,8452,17 ManaquiriAnori 51,0151,84 Anori 48,0551,01 Codajás 46,43 Barcelos 46,3148,05 CodajásAnamã 45,1946,43 44,21 BenjaminManacapuru Constant 43,2146,31 Anamã 42,9645,19 TapauáParintins 42,944,21 42,18 Benjamin ConstantHumaitá 42,143,21 Carauari 41,8442,96 Autazes 40,93 Parintins 38,5342,9 EnviraUarini 38,0742,18 Humaitá 36,4242,1 Careiro da Várzea 35,64 Urucará 35,3741,84 NovoAutazes Airão 34,7140,93 Elevado (a partir de75%) 34,59 BarreirinhaCareiro 33,938,53 Mediano (50% a 70%) Uarini 33,5638,07 Boa Vista doBeruri Ramos 32,1936,42 Deficiente (25% a 50%) 31,34 PresidenteCareiro da Figueiredo Várzea 31,2535,64 Crítico (maior 0% a 25%) São Paulo de Olivença 30,2835,37 NovoManicoré Airão 30,18 Inexistente 0% 29,7834,71 FonteItamarati Boa 28,3634,59 Barreirinha 27,9733,9 Santa Isabel do Rio Negro 27,78 Amaturá 25,8433,56 Boa VistaAtalaia do doRamos Norte 25,4432,19 Tabatinga 24,9831,34 Tonantins 24,71 Presidente Figueiredo 24,4231,25 São Gabriel da CachoeiraBorba 23,1830,28 Manicoré 23 30,18 Japurá 22,88 Eirunepé 21,4229,78 ItamaratiIpixuna 20,7728,36 20,1 NovaSanto Olinda Antônio do Norte do Içá 19,4227,97 Santa Isabel do Rio… 18,8927,78 CaapirangaNhamundá -

Autazes 2011.Doc INDICADOR DE DESENVOLVIMENTO HUMANO MUNICIPAL - IDH

AUTAZES Ato de Criação do município: Lei n. º 96 de 19/12/1955. @ AUTAZES ASPECTOS FÍSICOS E GEOGRÁFICOS: Localização: Situado na 7ª Sub-Região - Região do Rio Negro - Solimões. Limites: Itacoatiara, Nova Olinda do Norte, Borba, Careiro e Careiro da Várzea. Área Territorial: 7.986 Km² Distância da sede municipal para Manaus: Em linha reta 110 km Via fluvial 218 km Festas Religiosas: São Sebastião (20 de janeiro), São José (19 de março), Santo Antonio (13 de Junho), São João Batista (24 de junho), Sant’Ana (25 de junho), São Pedro (29 de junho), São Joaquim (16 de agosto), São Raimundo Nonato (31 de agosto), São Francisco de Assis (4 de outubro), Nossa Senhora Aparecida (12 de outubro), Nossa Senhora da Conceição (8 de dezembro). Festas Populares: Carnaval, Instalação do Município (3 de março), Festival Folclórico (junho), Autonomia do Amazonas (5 de setembro), Festa do Leite e Feita Agropecuária (novembro). Santo Padroeiro: São Joaquim. Rios Principais: Madeira, Preto do Pantaleão e Mutuca. Povo Indígena: Mura. Clima: Tropical quente-úmido Temperatura: Máxima de 38º C Mínima de 22º C Média de Fonte: Unidade Local ASPECTOS POPULACIONAIS: Nº de Comunidades Existentes: 97 População urbana: 12.634 habitantes População rural: 17.273 habitantes TOTAL: 29.907 habitantes Fonte: IBGE -Censo 2007 ASPECTOS INFRA-ESTRUTURAIS: Transporte aéreo: Sim Transporte rodoviário: Sim Transporte fluvial: Sim C:\Users\hsantos\Desktop\Perfis sócioeconômicos 2011\Autazes 2011.doc INDICADOR DE DESENVOLVIMENTO HUMANO MUNICIPAL - IDH AUTAZES (AM) Esperança de vida ao Taxa de alfabetização de Taxa bruta de freqüência Renda per capta Índice de esperança 66,567nascer adultos0,796 escolar0,717 87,615 de vida0,693 (IDHM -L) Índice de educação Índice de PIB (IDHM-R) Índice de Des.