Chapter 5 – the Political Geography of Racial Polarization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of the New Jim Crow and the Condemnation of Blackness

The Influence of Past Racism on Present Criminal Injustice 143 Review Essay The Influence of Past Racism on Criminal Injustice: A Review of The New Jim Crow and The Condemnation of Blackness Jelani Jefferson Exum THE NEW JIM CROW: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Color- blindness. By Michelle Alexander. New York: The New Press. 2010. THE CONDEMNATION OF BLACKNESS: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America. By Khalil Gibran Mu- hammad. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2010. There are books that, on their own, are informative and moving. But, of- tentimes, reading books together—one right after the other—compounds each works’ transformative power. Michelle Alexander’s much-needed report (calling it simply a book hardly does it justice), The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, can certainly stand on its own as an important statement about the current use of mass incarceration to maintain a racial caste system in the United States. The same strength can be found in The Condemnation 0026-3079/2012/5201-143$2.50/0 American Studies, 52:1 (2012): 143-152 143 144 Jelani Jefferson Exum of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America, Khalil Gibran Muhammad’s account of the connection of blackness to criminality in this country. Each book, on its own, gives readers a greater understanding of the racism within the criminal justice system. However, reading them jointly paints a disturbing picture of the past and present use of incarceration and crime rhetoric in America and leaves one with an overwhelming sense of injustice and the data to know that the injustice is real. -

The Impact of Black Political Representation on the Racial Attitudes, Policy Preferences, and Vote Choice of Whites in Minority Majority Congressional Districts

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2014 The Impact Of Black Political Representation On The Racial Attitudes, Policy Preferences, And Vote Choice Of Whites In Minority Majority Congressional Districts Emmitt Y. Riley University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Riley, Emmitt Y., "The Impact Of Black Political Representation On The Racial Attitudes, Policy Preferences, And Vote Choice Of Whites In Minority Majority Congressional Districts" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 787. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/787 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF BLACK POLITICAL REPRESENTATION ON THE RACIAL ATTITUDES, POLICY PREFERENCES, AND VOTE CHOICE OF WHITES IN MINORITY MAJORITY CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICTS by Emmitt Y. Riley III A Dissertation Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Political Science Oxford, Mississippi August 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Emmitt Y. Riley III ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Scholars examining black political representation have focused on the degree to which African American politicians can impact the everyday living conditions of African Americans. Despite years of African American political representation within the United States House of Representatives, political scientists have devoted very little scholarship to examining how whites react to African American leadership. Given that African Americans remain under represented in government and current legal challenges threaten the future of minority majority districts, it is important to gain better insight into how black representation might impact the white community. -

Facing Racism: a Vision of the Beloved Community

Facing Racism: A Vision of the Beloved Community Approved by The 211th General Assembly (1999) Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) Developed by The Initiative Team on Racism and Racial Violence Published by The Office of the General Assembly 100 Witherspoon Street Louisville, KY 40202-1396 Copyright © 1999 The Office of the General Assembly Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) Printed in the United States of America Cover design by the Office of the General Assembly Department of Communication and Technology No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, electronically, mechanically, photocopying, re- cording, or otherwise (brief quotations used in magazine or newspaper reviews ex- cepted), without the prior permission of the publisher. The sessions, presbyteries, and synods of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) may use sections of this publication without receiving prior written permission of the pub- lisher. Additional copies available from Presbyterian Distribution Service (PDS), 100 Witherspoon Street, Louisville, KY 40202-1396, or by calling 1-800-2612 (PDS) or OGA Sales 1-888-219-6700 Please specify PDS order #OGA-99-033 October 1999 To: Pastors of Churches and Clerks of Sessions Where There Is No Installed Pastor, and Stated Clerks and Executives of Presbyteries and Synods Dear Friends: The 211th General Assembly (1999) of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) has asked me to send you a copy of the policy statement on “Facing Racism: In Search of the Beloved Community.” The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) recognizes that the task of dismantling racism is a long-term struggle that requires discernment, prayer, and worship based action. -

The Effects of American Slavery on Contemporary Voting Institutions

A Culture of Disenfranchisement: How American Slavery Continues to Affect Voting Behavior * Avidit Acharya,† Matthew Blackwell,‡ and Maya Sen§ October 31, 2015 Abstract In Shelby County v. Holder (2013), the Supreme Court struck down parts of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 on the argument that intervening history had atten- uated many voting inequalities between blacks and whites. But how, where, and by how much have things changed, and does history still predict voting inequal- ities today? We show that parts of the American South where slavery was more prevalent in the 1860s are today areas with lower average black voter turnout, larger numbers of election lawsuits alleging race-related constitutional violations, and more racial polarization in party identification. To explain this, we develop a theory of behavioral path dependence, which we distinguish from other theories of path dependence. We show evidence of behavioral path dependence demon- strating that disenfranchisement can linger over time and that the effects of re- strictions on voting rights can persist culturally. *Comments and suggestions welcome. Many thanks to Tim Blessing, Gary King, Eitan Hersh, Nathan Kalmoe, J. Morgan Kousser, Douglas Spencer, Matthew Winters, Wendy Wright, and panel participants at the 2014 APSA, 2015 MPSA, and 2015 EPSA meetings for helpful feedback and suggestions. Thanks also to Heather O’Connell, Stephen Ansolabehere, and Ariel White for data assistance. †Assistant Professor, Stanford University. email: [email protected], web: http://www.stanford. edu/~avidit. ‡Assistant Professor, Harvard University. email: [email protected], web: http://www. mattblackwell.org. §Assistant Professor, Harvard University. email: [email protected], web: http://scholar. -

Evidence and Implications for VRA Preclearance After Shelby County

The Geography of Racial Stereotyping: Evidence and Implications for VRA Preclearance After Shelby County Christopher S. Elmendorf* Douglas M. Spencer** The Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder (2013) effectively enjoined the preclearance regime of the Voting Rights Act. The Court deemed the coverage formula, which determines the jurisdictions subject to preclearance, insufficiently grounded in current conditions. This Article proposes a new, legally defensible approach to coverage based on between-state differences in the proportion of voting age citizens who subscribe to negative stereotypes about racial minorities and who vote accordingly. The new coverage formula could also account for racially polarized voting and minority population size, but, for constitutional reasons, subjective discrimination by voters is the essential criterion. We demonstrate that the racial-stereotyping, polarized-voting, and population-size criteria would yield similar patterns of coverage, at least with respect to African Americans, and we show, ironically, that the new pattern of coverage would coincide with historic coverage under the “outdated” formula invalidated by Shelby County. Recently developed statistical techniques permit the new coverage formula to be further refined based on estimates of racial Copyright © 2014 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc. (CLR) is a California nonprofit corporation. CLR and the authors are solely responsible for the content of their publications. * Professor of Law, University of California, Davis. -

IMAN 2(3) Sept 2014

International Journal of the Malay World and Civilisation (Iman) 2(3), 2014: 67 - 75Ding Choo Ming 67 Some Challenges in Managing Cultural Differences in a Multi-Ethnic Country: Malaysia DING CHOO MING ABSTRACT To develop an united nation of different ethnic groups is hard. It requires the ability of all the people from different ethnic groups to understand, communicate and interact with one another and work together to create a broad-and-inclusive space for new national political discourse to replace the existing narrow-and-exclusive political interests. This would involve a new cultural competence and cultural literacy which include awareness of one’s own cultural worldview and attitude towards the cultural differences, knowledge of different cultural practices and worldviews, and cross-cultural skills. As it is, many Malaysians have learnt and developed the skills, but many others have not. This would involve a process to continuously examine biases and prejudices to develop new cross-cultural skills to share a passion for cultural competence. Malaysia has a rich cultural diversity that could be harnessed for the nation’s benefit. Sadly, the differences among us form the bases of fear, suspicion, misunderstanding, clashes and conflict. Just consider how dull life would it be if we all look, think and act alike. By learning to recognise our similarities and appreciate our differences, we can overcome prejudice and work towards a more peaceful and productive nation. This article touches on the importance of education in the broadest meaning of learning to accept and respect the differences as the right way to everyone from different ethnic groups to grasp the values, norms, and traditions which would affect how we perceive, think, interact and share the nation with one another. -

Tables and Figures

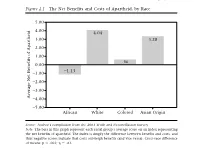

Apartheid’s Legacy 45 Figure 2.1 The Net Benefits and Costs of Apartheid, by Race 5.00 4.00 4.04 3.00 3.28 2.00 1.00 .56 0.00 −1.13 −1.00 −2.00 −3.00 Average Net Benefits of Apartheid Average −4.00 −5.00 African White Colored Asian Origin Source: Author’s compilation from the 2001 Truth and Reconciliation Survey. Note: The bars in this graph represent each racial group’s average score on an index representing the net benefits of apartheid. The index is simply the difference between benefits and costs, and thus negative scores indicate that costs outweigh benefits (and vice versa). Cross-race difference .63. ס ;of means: p Ͻ .001 to 4.0 among whites (with standard deviations in the range of about 2.5 to 3.8). Among blacks, 34.9 percent have a score of 0, while 14.2 percent were net beneficiaries of apartheid; among whites, for 20.3 percent apartheid was a wash on the factors con- sidered here, while 76.7 percent see themselves as net beneficiaries (data not shown). Those of Asian origin tend to have profited from apartheid (69.8 percent), while Colored South Africans are almost equally divided in terms of having benefited, having been harmed, and coming out even from apartheid.19 The old apartheid system meant quite different things for the different races in South Africa. Moreover, the groups conventionally classified as “Black” did not fare the same under apartheid. 34 Overcoming Apartheid Table 2.1 Demographic Attributes of South Africa’s Racial Groups Asian Attribute African White Colored Origin Gender Percentage female 50.1% 50.7% -

The New Jim Crow

For Nicole, Jonathan, and Corinne Acknowledgments It is often said, “It takes a village to raise a child.” In my case, it has taken a village to write this book. I gave birth to three children in four years, and in the middle of this burst of joyous activity in our home, I decided to write this book. It was written while feeding babies and during nap times. It was written at odd hours and often when I (and everyone else in the household) had little sleep. Quitting the endeavor was tempting, as writing the book proved far more challenging than I expected. But just when I felt it was too much or too hard, someone I loved would surprise me with generosity and unconditional support; and just when I started to believe the book was not worth the effort, I would receive—out of the blue—a letter from someone behind bars who would remind me of all the reasons that I could not possibly quit, and how fortunate I was to be sitting in the comfort of my home or my office, rather than in a prison cell. My colleagues and publisher supported this effort, too, in ways that far exceeded the call of duty. I want to begin, then, by acknowledging those people who made sure I did not give up—the people who made sure this important story got told. First on this list is Nancy Rogers, who was dean of the Moritz College of Law at Ohio State University until 2008. Nancy exemplifies outstanding leadership. -

Democracy, Majoritarianism, and Racial Equality: a Response to Professor Karlan

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 50 Issue 2 Issue 2 - Symposium: Defining Article 5 Democracy for the Next Century 3-1997 Democracy, Majoritarianism, and Racial Equality: A Response to Professor Karlan Christopher L. Eisgruber Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Christopher L. Eisgruber, Democracy, Majoritarianism, and Racial Equality: A Response to Professor Karlan, 50 Vanderbilt Law Review 347 (1997) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol50/iss2/5 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Democracy, Majoritarianism, and Racial Equality: A Response to Professor Karlan ChristopherL. Eisgruber* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 347 II. THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF MAJORITY-BLACK D ISTRICTS ........................................................................... 349 III. THE POSSIBILITY OF ASSEMBLY BACKLASH ....................... 352 IV. THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN DEMOCRACY AND MAJORITARIANISM ............................................................. 354 V. RACIAL EQUALITY AND AMERICAN POLITICS ...................... 356 VI. CONCLUSION ...................................................................... 359 I. INTRODUCTION Only with great trepidation -

The Asian American Movement's Vision of Racial and Political Solidarity

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1995 Creating a panethnic identity: The Asian American movement's vision of racial and political solidarity Rosette Ho Wirtz University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Wirtz, Rosette Ho, "Creating a panethnic identity: The Asian American movement's vision of racial and political solidarity" (1995). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 490. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/85km-yaww This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. U M I films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in ^pewriter face, while others may be from aity type of con^uter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photogr^hs, prin t bleedthrough, substandard margins, and inqjropera lignm e n tcan adversely affect reproduction. -

The New Jim Crow : Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness / Michelle Alexander

© 2010 by Michelle Alexander All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. Request for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 38 Greene Street, New York, NY 10013. Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2010 Distributed by Perseus Distribution library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Alexander, Michelle. The new Jim Crow : mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness / Michelle Alexander. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59558-103-7 (hc. : alk. paper) 1. Criminal justice, Administration of— United States. 2. African American prisoners—United States. 3. Race discrimination— United States. 4. United States—Race relations. I. Title. HV9950.A437 2010 364.973—dc22 2009022519 The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profi t alternative to the large, commerical publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insuffi ciently profi table. www.thenewpress.com Composition by NK Graphics This book was set in Fairfi eld LH Light Printed in the United States of America 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 1 The Rebirth of Caste [T]he slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slav ery. —W.E.B Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America For more than one hundred years, scholars have written about the illusory nature of the Emancipation Proclamation. -

202008 Polarization

Polarization and reconciliation systems perspectives using racism as a case study by Marina Paraï Contents Introduction 3 Part I - Factors of polarization between black and white people 5 History, influencing the system, explains durable polarization 9 American racism history and the birth of polarization 9 European history of racism: a comparison 12 History and its institutions continue to shape attitudes and behaviours 12 Racialized policies and practices create, maintain and accentuate polarization. 14 Institutionalisation of practices 14 Public policies and practices enhance and maintain polarization 14 Housing 15 Banking 18 Education 20 Employment 22 Health 24 Welfare 26 Formation of durable assumptions locked in racial polarization. 27 Part II - Other practices that support a racist dynamic of society 31 Family 31 Language 33 Intersectionality 33 People in executive committees are mainly white. 35 Police violence towards black people 36 Marina Paraï, August 2020, Page 1 Judiciary system 38 Surveillance 39 Media 40 Polarization of the world 41 Reducing polarization between white and black people 43 More awareness from people allows fighting against bias. 44 Better representation in all areas allows black people to have a place in society 48 Historical consensus appeases tensions: rethinking our environment 54 An international response? 61 Conclusion 62 References 63 Marina Paraï, August 2020, Page 2 Introduction On the 25th of May 2020, George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man was arrested and killed by the police in Minneapolis, USA. Dereck Chauvin, a white police officer knelt on him for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, having suspected him of using a false twenty-dollar bill.