Dutchman (Jones 1964/Harvey 1966)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesleywalker

(3/10/21) LESLEY WALKER Editor FILM & TELEVISION DIRECTOR COMPANIES PRODUCERS “MILITARY WIVES” Peter Cattaneo 42 Rory Aitken Tempo Productions Ltd. Ben Pugh “THE MAN WHO KILLED DON Terry Gilliam Amazon Studios Mariela Besuievsky QUIXOTE” Recorded Picture Co. Amy Gilliam Gerardo Herrero Gabriele Oricchio “THE DRESSER” Richard Eyre BBC Suzan Harrison Playground Ent. Colin Callender “MOLLY MOON: THE Christopher N. Rowley Amber Ent. Lawrence Elman INCREDIBLE HYPNOTIST” Lipsync Prods. Ileen Maisel “HOLLOW CROWN: HENRY IV”Richard Eyre BBC Rupert Ryle-Hodges Neal Street Prods. Sam Mendes “I AM NASRINE” Tina Gharavi Bridge and Tunnel Prods James Richard Baille (Supervising Editor) David Raedeker “WILL” Ellen Perry Strangelove Films Mark Cooper Ellen Perry Taha Altayli “MAMMA MIA” Phyllida Lloyd Playtone Gary Goetzman Nomination: American Cinema Editors (ACE) Award Universal Pictures Tom Hanks Rita Wilson “CLOSING THE RING” Richard Attenborough Closing the Ring Ltd. Jo Gilbert “BROTHERS GRIMM” Terry Gilliam Miramax Daniel Bobker Charles Roven “TIDELAND” Terry Gilliam Capri Films Gabriella Martinelli Recorded Picture Co. Jeremy Thomas “NICHOLAS NICKLEBY” Douglas McGrath Cloud Nine Ent. S. Channing Williams Hart Sharp Entertainment John Hart MGM/United Artists Jeffery Sharp “ALL OR NOTHING” Mike Leigh Cloud Nine Entertainment Simon Channing Williams Le Studio Canal “SLEEPING DICTIONARY” Guy Jenkin Fine Line Simon Bosanquet "FEAR AND LOATHING IN Terry Gilliam Rhino Patrick Cassavetti LAS VEGAS" Stephen Nemeth "ACT WITHOUT WORDS I" Karel Reisz Parallel -

Teaching World History with Major Motion Pictures

Social Education 76(1), pp 22–28 ©2012 National Council for the Social Studies The Reel History of the World: Teaching World History with Major Motion Pictures William Benedict Russell III n today’s society, film is a part of popular culture and is relevant to students’ as well as an explanation as to why the everyday lives. Most students spend over 7 hours a day using media (over 50 class will view the film. Ihours a week).1 Nearly 50 percent of students’ media use per day is devoted to Watching the Film. When students videos (film) and television. With the popularity and availability of film, it is natural are watching the film (in its entirety that teachers attempt to engage students with such a relevant medium. In fact, in or selected clips), ensure that they are a recent study of social studies teachers, 100 percent reported using film at least aware of what they should be paying once a month to help teach content.2 In a national study of 327 teachers, 69 percent particular attention to. Pause the film reported that they use some type of film/movie to help teach Holocaust content. to pose a question, provide background, The method of using film and the method of using firsthand accounts were tied for or make a connection with an earlier les- the number one method teachers use to teach Holocaust content.3 Furthermore, a son. Interrupting a showing (at least once) national survey of social studies teachers conducted in 2006, found that 63 percent subtly reminds students that the purpose of eighth-grade teachers reported using some type of video-based activity in the of this classroom activity is not entertain- last social studies class they taught.4 ment, but critical thinking. -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß. -

Cuaderno Junio2019 CAINE Opt.Pdf

La noticia de la primera sesión del Cineclub de Granada Periódico “Ideal”, miércoles 2 de febrero de 1949. El CINECLUB UNIVERSITARIO se crea en 1949 con el nombre de “Cineclub de Granada”. Será en 1953 cuando pase a llamarse con su actual denominación. Así pues en este curso 2018-2019, cumplimos 65 (69) años. 3 MAYO - JUNIO 2019 MAY - JUNE 2019 UN ROSTRO EN LA PANTALLA (V): A FACE ON THE SCREEN (V): MICHAEL CAINE MICHAEL CAINE ( part 2: the 70’s/I ) ( 2ª parte: los años 70/I ) Martes 28 mayo / Tuesday 28th may 21 h. COMANDO EN EL MAR DE CHINA (1970) Robert Aldrich ( TOO LATE THE HERO ) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Viernes 31 mayo / Friday 31th may 21 h. EL ÚLTIMO VALLE (1971) James Clavell ( THE LAST VALLEY ) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 4 junio / Tuesday 4th june 21 h. ASESINO IMPLACABLE (1971) Mike Hodges ( GET CARTER ) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Viernes 7 junio / Friday 7th june 21 h. LA HUELLA (1972) Joseph L. Mankiewicz ( SLEUTH ) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles 4 A FACE ON THE SCREEN (V): MICHAEL CAINE ( part 2: the 70’s/I ) Todas las proyecciones en la SALA MÁXIMA del ESPACIO V CENTENARIO (Av. de Madrid). Entrada libre hasta completar aforo Free admission up to full room 5 Martes 28 de mayo 21 h. Sala Máxima del Espacio V Centenario Entrada libre hasta completar aforo COMANDO EN EL MAR DE CHINA (1970) EE.UU. -

Dlkj;Fdslk ;Lkfdj

MoMA CELEBRATES THE 75th ANNIVERSARY OF THE NEW YORK FILM CRITICS CIRCLE BY INVITING MEMBERS TO SELECT FILM FOR 12-WEEK EXHIBIITON Critical Favorites: The New York Film Critics Circle at 75 July 3—September 25, 2009 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters & The Celeste Bartos Theater NEW YORK, June 19, 2009 —The Museum of Modern Art celebrates The New York Film Critics Circle’s (NYFCC) 75th anniversary with a 12-week series of award-winning films, from July 3 to September 25, 2009, in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters. As the nation‘s oldest and most prestigious association of film critics, the NYFCC honors excellence in cinema worldwide, giving annual awards to the ―best‖ films in various categories that have all opened in New York. To mark the group‘s milestone anniversary, each member of the organization was asked to choose one notable film from MoMA‘s collection that was a recipient of a NYFCC award to be part of the exhibition. Some screenings will be introduced by the contributing film critics. Critical Favorites: The New York Film Critics Circle at 75 is organized by Laurence Kardish, Senior Curator, Department of Film, in collaboration with The New York Film Critics Circle and 2009 Chairman Armond White. High-resolution images are available at www.moma.org/press. No. 58 Press Contacts: Emily Lowe, Rubenstein, (212) 843-8011, [email protected] Tessa Kelley, Rubenstein, (212) 843-9355, [email protected] Margaret Doyle, MoMA, (212) 408-6400, [email protected] Film Admission: $10 adults; $8 seniors, 65 years and over with I.D. -

Programma 2015

RAGUSA / Castello di Donnafugata ZODIAC FILM FESTIVAL / L’ISOLA COME SET 14/23 AGOSTO 2015 VII EDIZIONE srl www.agriplast.com Città di Ragusa programma > ZodiacFilmFest ZFF/L’isola come set DFFF ZodiacFilmFest il motto di quest’anno è E va bene, cosa da niente, tutto si accomoda pacatamente... 14/23 agosto 2015 da Leoni al sole di Vittorio Caprioli Ragusa Castello di Donnafugata [VII Edizione] ARENA DEL CASTELLO Venerdì 14 agosto IL RUGGITO DEL LEONE|FILM MUTI MGM (E NON SOLO) ore 21,00 Cineclub Leone. Cecil B.DeMille SALA BIANCA The Squaw Man (Usa, 1914, 74’) di Cecil B.DeMille e Oscar Apfel The Cheat (Usa 1915, 59’) di Cecil B.DeMille LEONI D’ORO|PERLE AI CINEFILINTO SPECIA Carmen (Usa, 1915, 87’) di Cecil B.DeMille ore 17,00 Cineclub Leone. Paul Gégauff e Michèle Girardon UNA NOTTE DA LEONI|COMMEDIE INDIMENTICABILI Il segno del leone (Francia, 1959, 103’) di Éric Rohmer ore 00,30 Cineclub Leone. Steve Carell LA PARTE DEL LEONE|GRANDI RUOLI, GRANDI Attori 40 anni vergine (Usa, 2005, 116’) di Judd Apatow ore 19,00 Cineclub Leone. Peter O’ Toole Il leone d’inverno (Regno Unito, 1968, 134’) di Anthony Harvey CORTILE GRANDE ore 21,00 Cineclub Leone. Francesco Calogero TERRAZZO DEL CASTELLO promoreel Seconda primavera (Italia, 2015, 6’) di Francesco Calogero a seguire Cineclub Leone. Francesco Calogero, Antonio Alveario GUARDANDO IL TRAMONTO|I POETI E HARMATTAN Visioni private (Italia, 1990, 92’) di N. Bruschetta, F. Calogero e D. Ranvaud ore 19,00 Prima della notte di Zima/Africana Sulle percussioni di Harmattan a seguire L’Isola come set La mafia uccide solo d’estate (Italia, 2013, 90’) di Pif con A. -

BIBLIOTECA PÚBLICA MUNICIPAL DE TEBA VIDEOTECA Listado De Películas Disponibles

BIBLIOTECA PÚBLICA MUNICIPAL DE TEBA VIDEOTECA _ Listado de películas disponibles TÍTULO AUTOR 01 21 gramos Alejando González Iñárritu 02 Ágora Alejandro Amenábar 03 Alejandro Magno Oliver Stone 04 Amanece que no es poco José Luis Cuerda 05 American beauty Sam Méndez 06 American history X Tony Kaye 07 Andalucía se mueve con Europa Junta de Andalucía Antes que el diablo sepa que 08 has muerto Sidney Lumet 09 Apocalypse now Francis Ford Coppola 10 Atrapado en el tiempo Harold Ramis 11 Avatar James Cameron 12 Babel Alejandro González Iñárritu 13 Belle époque Fernando Trueba 14 Bienvenido Mr. Marshall Luis García Berlanga 15 Big fish Tim Burton 1 TÍTULO AUTOR 16 Birdman Alejandro González 17 Boy’s don’t cry Kimberly Peirce 18 Brave Disney 19 Campeones Javier Fesser 20 Captain fantasic Matt Ross 21 Celda 211 Daniel Monzón 22 Cine bélico 1 Directores varios 23 Cine bélico 2 Directores varios 24 Cine bélico 3 Directores varios 25 Cine bélico 4 Directores varios 26 Cine de acción 1 Directores varios 27 Cine de acción 2 Directores varios 28 Cine de acción 3 Directores varios 29 Cine de Oro Divas Crin 30 Cine del Oeste 1 Directores varios 2 TÍTULO AUTOR 31 Cine del Oeste 2 Directores varios 32 Cine del Oeste 3 Directores varios 33 Cine del Oeste 4 Directores varios 34 Cine épico Directores varios 35 Coco Disney 36 Comandante Oliver Stone 37 Coriolanus Ralph Fiennes 38 Corto en femenino 2009 Ministerio de Igualdad 39 Cortos 2018 Junta de Andalucía 40 Cosmos Karl Sagan 41 Cuatro jardines para Pablo Junta de Andalucía 42 Dallas Buyer’s Club Jean-Marc -

Email: [email protected] ZWEI LEBEN

- Herengracht 328 III - 1016 CE Amsterdam - T: 020 5308848 - email: [email protected] ZWEI LEBEN Een film van Georg Maas Katrine is opgegroeid in Oost-Duitsland en woont al 20 jaar in Noorwegen. Ze is het kind van een Duitse soldaat en een Noorse vrouw die een relatie hadden tijdens WO II. Na haar geboorte werd Katrine in een weeshuis geplaatst. Jaren later weet ze de DDR te ontvluchten en vindt ze haar moeder terug in Noorwegen. Wanneer een advocaat haar niet lang na de val van de muur vraagt om te getuigen in naam van de ‘kinderen van de schaamte’ in een rechtszaak tegen de Noorse staat, weigert Katrine dit: ze heeft er geen enkel belang bij in haar verleden te duiken. Geleidelijk komen haar donkere geheimen naar boven en wordt duidelijk dat de Stasi, de geheime dienst van de DDR, een grote rol gespeeld heeft in het leven van deze kinderen. Winnaar NDR Audience Award - Emden International Film Festival 2013 Winnaar Beste Film - Biberach Film Festival 2012 Winnaar Beste Film - Biberach Independent Film Festival 2012 Winnaar NDR Audience Award - Emden International Film Festival 2011 Winnaar Closing Night Film - Stony Brook Film Festival 2013 Land: Duitsland – Jaar: 2014 – Genre: Drama – Speelduur: 97 min. Releasedatum: 17-07-2014 Distributie: Cinéart Meer informatie over de film: Cinéart Nederland - Janneke De Jong Herengracht 328 III / 1016 CE Amsterdam Tel: +31 (0)20 5308844 Email: [email protected] www.cineart.nl Persmap en foto’s staan op: www.cineart.nl Persrubriek - inlog: cineart / wachtwoord: film - Herengracht 328 III - 1016 -

Lionwinter Studyguide.Pdf

McGuire Proscenium Stage / Nov 19 – Dec 31, 2016 by JAMES GOLDMAN STUDY GUIDE Inside THE PLAYWRIGHT Biography of James Goldman • 3 Comments about the Playwright • 4 THE PLAY Synopsis, Characters and Setting • 5 Historical Note about The Lion in Winter • 6 A Brief Production History and Analysis of The Lion in WInter • 7 Comments about the Play • 8 Quotes about the Play • 10 CULTURAL CONTEXT Notes about the 12th Century • 11 Biographies of the Historical Personages in the Play • 13 Parents, Children and Siblings • 16 Selected Glossary of Terms • 17 THE GUTHRIE PRODUCTION Notes from the Creative Team • 22 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION For Further Understanding • 25 Play guides are made possible by Guthrie Theater Study Guide Copyright 2016 DRAMATURG Carla Steen GRAPHIC DESIGNER Akemi Waldusky RESEARCH Stephanie Engel, Carla Steen All rights reserved. With the exception of classroom use by teachers and Guthrie Theater, 818 South 2nd Street, Minneapolis, MN 55415 individual personal use, no part of this Play Guide may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including ADMINISTRATION 612.225.6000 photocopying or recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Some materials BOX OFFICE 612.377.2224 or 1.877.44.STAGE TOLL-FREE published herein are written especially for our Guide. Others are reprinted guthrietheater.org • Joseph Haj, artistic director by permission of their publishers. Jo Holcomb: 612.225.6117 | Carla Steen: 612.225.6118 The Guthrie Theater, founded in 1963, is an American center for theater performance, The Guthrie Theater receives support from the National Endowment production, education and professional training. -

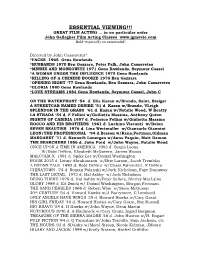

John's Definitive Movie List

ESSENTIAL VIEWING!!! GREAT FILM ACTING … in no particular order John Gallagher Film Acting Classes www.jgmovie.com Bold=especially recommended! Directed by John Cassavetes* *FACES 1968 Gena Rowlands *HUSBANDS 1970 Ben Gazzara, Peter Falk, John Cassavetes *MINNIE AND MOSKOWITZ 1971 Gena Rowlands, Seymour Cassel *A WOMAN UNDER THE INFLUENCE 1975 Gena Rowlands *KILLING OF A CHINESE BOOKIE 1976 Ben Gazzara *OPENING NIGHT ‘77 Gena Rowlands, Ben Gazzara, John Cassavetes *GLORIA 1980 Gena Rowlands *LOVE STREAMS 1984 Gena Rowlands, Seymour Cassel, John C ON THE WATERFRONT ‘54 d. Elia Kazan w/Brando, Saint, Steiger A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE ’51 d. Kazan w/Brando, VLeigh SPLENDOR IN THE GRASS ‘61 d. Kazan w/Natalie Wood, W Beatty LA STRADA ‘54 d. F Fellini w/Guilietta Massina, Anthony Quinn NIGHTS OF CABIRIA 1957 d. Federico Fellini w/Giulietta Massina ROCCO AND HIS BROTHERS 1961 d. Luchino Visconti w/Delon SEVEN BEAUTIES 1976 d. Lina Wertmuller w/Giancarlo Giannini LEON/THE PROFESSIONAL ‘94 d.Besson w/Reno,Portman,Oldman MARGARET ’11 d. Kenneth Lonergan w/Anna Paquin, Matt Damon THE SEARCHERS 1956 d. John Ford w/John Wayne, Natalie Wood ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA 1983 d. Sergio Leone W/Robt DeNiro, Elizabeth McGovern, James Woods MALCOLM X 1991 d. Spike Lee w/Denzel Washington ROOM 2015 d. Lenny Abrahamson w/Brie Larson, Jacob Tremblay A BRONX TALE 1993 d. Robt DeNiro w/Chazz Palminteri, R DeNiro CHINATOWN ‘74 d. Roman Polanski w/Jack Nicholson, Faye Dunaway THE LAST DETAIL 1973 d. Hal Ashby w/Jack Nicholson BEING THERE 1979 d. Hal Ashby w/Peter Sellers, Shirley MacLaine GLORY 1989 d. -

E the Other Hollywood Renaissance

EDITED BY DOMINIC LENNARD, R. BARTON PALMER AND, PALMER BARTON R. Traditions in American Cinema POMERANCE MURRAY Series Editors: Linda Badley and R. Barton Palmer This series explores a wide range of traditions in American cinema which are in need of introduction, investigation or critical reassessment. It emphasises the multiplicity rather than the supposed homogeneity of studio-era and independent filmmaking, making a case that the American cinema is more diverse than some accounts might suggest. THE OTHER HOLLYWOOD RENAISSANCE In the late 1960s, the collapse of the classic Hollywood studio system led in part, and for less than a decade, to a production trend heavily influenced by the international art cinema. Reflecting a new self-consciousness in the US about the national film patrimony, RENAISSANCE HOLLYWOOD THE OTHER this period is known as the Hollywood Renaissance. However, critical study of the period is generally associated with its so-called principal auteurs, slighting a number of established and emerging directors who were responsible for many of the era’s most innovative and artistically successful releases. With contributions from leading film scholars, this book provides a revisionist account EDITED BY DOMINIC LENNARD, R. BARTON PALMER, of this creative resurgence by discussing and memorializing twenty-four directors of note who have not yet been given a proper place in the larger history of the period. Including AND MURRAY POMERANCE filmmakers such as Hal Ashby, John Frankenheimer, Mike Nichols, and Joan Micklin Silver, this more expansive approach to the auteurism of the late 1960s and 1970s seems not only appropriate but pressing – a necessary element of the re-evaluation of “Hollywood” with THE OTHER which cinema studies has been preoccupied under the challenges posed by the emergence and flourishing of new media. -

Two Lives Pressbook

presents TWO LIVES Written and directed by Georg Maas Co-Authors Christoph Tölle, Ståle Stein Berg, Judith Kaufmann Starring Juliane Köhler, Liv Ullmann, Ken Duken, Sven Nordin, Rainer Bock Produced by Zinnober Film (Dieter Zeppenfeld), Helgeland Film (Axel Helgeland) and B & T Film (Rudi Teichmann) in co-production with Degeto Film, ApolloMedia, TV2, C More Entertainment and FUZZ Supported by Filmstiftung NRW, Filmförderung Hamburg Schleswig-Holstein, DFFF, MEDIA Development, Norwegian Film Institut, Vestnorsk and FUZZ German Release by farbfilm Verleih CREW Director Georg Maas Script Georg Maas, Christoph Tolle, S t å le Stein Berg, Judith Kaufmann Production Zinnober Film, Dieter Zeppenfeld Helgeland Film, Axel Helgeland B & T Film, Rudi Teichmann D.O.P. Judith Kaufmann Editor Hansjorg Weissbrich Art Department Bader El Hindi Costume Ute Paffendorf Make up Susana Sanchez Nunez Sound Thomas Angell Endresen Music Christoph M. Kaiser & Julian Maas Sounddesign Dirk Jacobs 2 For further information: Beta Cinema Press, Dorothee Stoewahse, Tel: + 49 89 67 34 69 15, Mobile: + 49 170 63 84 627 [email protected] , www.betacinema.com . Pictures and filmclips available on ftp.betafilm.com , username: ftppress01, password: 8uV7xG3tB CAST KATRINE EVENSEN MYRDAL Juliane Kohler ASE EVENSEN Liv Ullmann BJARTE MYRDAL Sven Nordin ATTORNEE SVEN SOLBACH Ken Duken ANNE MYRDAL Julia Bache-Wiig HUGO Rainer Bock KONTAKTMANN IN NORWEGEN Thomas Lawinky KATRINE EVENSEN (Young) Klara Manzel KATHRIN LEHNHABER Vicky Krieps ATTORNEE HOGSETH Dennis Storhoi HILTRUD