Chatham Lights by Spencer Grey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historically Famous Lighthouses

HISTORICALLY FAMOUS LIGHTHOUSES CG-232 CONTENTS Foreword ALASKA Cape Sarichef Lighthouse, Unimak Island Cape Spencer Lighthouse Scotch Cap Lighthouse, Unimak Island CALIFORNIA Farallon Lighthouse Mile Rocks Lighthouse Pigeon Point Lighthouse St. George Reef Lighthouse Trinidad Head Lighthouse CONNECTICUT New London Harbor Lighthouse DELAWARE Cape Henlopen Lighthouse Fenwick Island Lighthouse FLORIDA American Shoal Lighthouse Cape Florida Lighthouse Cape San Blas Lighthouse GEORGIA Tybee Lighthouse, Tybee Island, Savannah River HAWAII Kilauea Point Lighthouse Makapuu Point Lighthouse. LOUISIANA Timbalier Lighthouse MAINE Boon Island Lighthouse Cape Elizabeth Lighthouse Dice Head Lighthouse Portland Head Lighthouse Saddleback Ledge Lighthouse MASSACHUSETTS Boston Lighthouse, Little Brewster Island Brant Point Lighthouse Buzzards Bay Lighthouse Cape Ann Lighthouse, Thatcher’s Island. Dumpling Rock Lighthouse, New Bedford Harbor Eastern Point Lighthouse Minots Ledge Lighthouse Nantucket (Great Point) Lighthouse Newburyport Harbor Lighthouse, Plum Island. Plymouth (Gurnet) Lighthouse MICHIGAN Little Sable Lighthouse Spectacle Reef Lighthouse Standard Rock Lighthouse, Lake Superior MINNESOTA Split Rock Lighthouse NEW HAMPSHIRE Isle of Shoals Lighthouse Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse NEW JERSEY Navesink Lighthouse Sandy Hook Lighthouse NEW YORK Crown Point Memorial, Lake Champlain Portland Harbor (Barcelona) Lighthouse, Lake Erie Race Rock Lighthouse NORTH CAROLINA Cape Fear Lighthouse "Bald Head Light’ Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Cape Lookout Lighthouse. Ocracoke Lighthouse.. OREGON Tillamook Rock Lighthouse... RHODE ISLAND Beavertail Lighthouse. Prudence Island Lighthouse SOUTH CAROLINA Charleston Lighthouse, Morris Island TEXAS Point Isabel Lighthouse VIRGINIA Cape Charles Lighthouse Cape Henry Lighthouse WASHINGTON Cape Flattery Lighthouse Foreword Under the supervision of the United States Coast Guard, there is only one manned lighthouses in the entire nation. There are hundreds of other lights of varied description that are operated automatically. -

Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area

Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area PHOTO: KEN MALLORY PHOTO: KEN MALLORY PHOTO: KEN MALLORY Peddocks Island Boston Harbor Boston Light looking toward Boston Harbor Over Hull and Worlds End looking back to Islands National Park Area Boston Harbor ollowing Professor E.O. Wilson’s March address to the Three rivers — the Charles, the Mystic, and the Neponset Massachusetts Land Trust meeting that drew attention — arranged like spokes on a wheel, feed into the harbor. Fto National Parks as corridors for preservation of The result: a network of urban estuaries where wildlife plant and animal species, a brief introduction to the Boston thrives, despite its proximity to one of the nation’s most Harbor National Park area seems all the more pertinent to populated metropolitan regions. Newton Conservators and their mandate to preserve open spaces. As the park opened for visitation this spring beginning May 13, ferryboats to Spectacle and Georges Island offered Designated a national park by an act of Congress in 1996, a first look at some of the harbor’s large variety of wildlife the 34 islands range in size from including migrating and resident less than one acre — Nixes Mate, birds. Then beginning in late The Graves, Shag Rocks, and June and running to Labor Day, Hangman — to Long Island’s 274 additional ferry service is available acres. All of the islands lie within to Bumpkin, Grape, Lovells, the large “C” shape of Boston and Peddocks, where overnight Harbor. The farthest island out, camping facilities are available. The Graves, sits 11 miles from shore. According to the park’s web site, the Massachusetts Natural Once an expanse of marshy plains Heritage Program lists six rare and elongated, gently sloping species known to exist within hills called drumlins, the basin PHOTO: KEN MALLORY the park, including two species containing the Boston Harbor listed as threatened and four Great Egret chicks on one of the harbor islands Islands National Park Area was of special concern. -

Cape Cod Lighthouses TCCI

Cape Cod Lighthouses Locations Click on a lighthouse on the map for more information The climb up circular stairs to the top of a lighthouse tower is not for the squeamish or for those afraid of heights. Most lighthouses have interesting stories related to their history. Some are open to the public and have “visiting hours.” Others are open only on special occasions. Usually a tour guide will take you through the building and offer you tales of lighthouse living. The winding staircases, the distant echo of your footsteps, waves hitting against the rock, distant ship hooting…that’s the dejavu you get when you visit the Cape Cod Lighthouses. It is as if you are part of the whole system that emits navigational lights to guide hundreds of ships to dock safely. Lighthouses are navigational aids that mark the perilous reeds, hazardous shoals and poorly charted coastlines for safe harbor entry. Once upon a time, the lighthouses were the marine pilot’s most important aids but the advent of electronic navigation has led to their decline. The system of lights and lamps on the lighthouses are also expensive to maintain. The vantage points occupied by the lighthouses make them a tourists’ attraction. You’ll go up the winding staircase with your pair of binoculars and voila! The beautiful Cape Cod Coastline spreads right before your eyes. Race Point Light Located in Provincetown, Massachusetts, the Race Point Lighthouse is one of the historical building in the National Register of Historic Places. It was first built in 1816, but the current 45-foot tall tower was built in 1876. -

Pirates and Buccaneers of the Atlantic Coast

ITIG CC \ ',:•:. P ROV Please handle this volume with care. The University of Connecticut Libraries, Storrs Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Lyrasis Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/piratesbuccaneerOOsnow PIRATES AND BUCCANEERS OF THE ATLANTIC COAST BY EDWARD ROWE SNOW AUTHOR OF The Islands of Boston Harbor; The Story of Minofs Light; Storms and Shipwrecks of New England; Romance of Boston Bay THE YANKEE PUBLISHING COMPANY 72 Broad Street Boston, Massachusetts Copyright, 1944 By Edward Rowe Snow No part of this book may be used or quoted without the written permission of the author. FIRST EDITION DECEMBER 1944 Boston Printing Company boston, massachusetts PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN MEMORY OF MY GRANDFATHER CAPTAIN JOSHUA NICKERSON ROWE WHO FOUGHT PIRATES WHILE ON THE CLIPPER SHIP CRYSTAL PALACE PREFACE Reader—here is a volume devoted exclusively to the buccaneers and pirates who infested the shores, bays, and islands of the Atlantic Coast of North America. This is no collection of Old Wives' Tales, half-myth, half-truth, handed down from year to year with the story more distorted with each telling, nor is it a work of fiction. This book is an accurate account of the most outstanding pirates who ever visited the shores of the Atlantic Coast. These are stories of stark realism. None of the arti- ficial school of sheltered existence is included. Except for the extreme profanity, blasphemy, and obscenity in which most pirates were adept, everything has been included which is essential for the reader to get a true and fair picture of the life of a sea-rover. -

Celebrating 30 Years

VOLUME XXX NUMBER FOUR, 2014 Celebrating 30 Years •History of the U.S. Lighthouse Society •History of Fog Signals The•History Keeper’s of Log—Fall the U.S. 2014 Lighthouse Service •History of the Life-Saving Service 1 THE KEEPER’S LOG CELEBRATING 30 YEARS VOL. XXX NO. FOUR History of the United States Lighthouse Society 2 November 2014 The Founder’s Story 8 The Official Publication of the Thirty Beacons of Light 12 United States Lighthouse Society, A Nonprofit Historical & AMERICAN LIGHTHOUSE Educational Organization The History of the Administration of the USLH Service 23 <www.USLHS.org> By Wayne Wheeler The Keeper’s Log(ISSN 0883-0061) is the membership journal of the U.S. CLOCKWORKS Lighthouse Society, a resource manage- The Keeper’s New Clothes 36 ment and information service for people By Wayne Wheeler who care deeply about the restoration and The History of Fog Signals 42 preservation of the country’s lighthouses By Wayne Wheeler and lightships. Finicky Fog Bells 52 By Jeremy D’Entremont Jeffrey S. Gales – Executive Director The Light from the Whale 54 BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS By Mike Vogel Wayne C. Wheeler President Henry Gonzalez Vice-President OUR SISTER SERVICE RADM Bill Merlin Treasurer Through Howling Gale and Raging Surf 61 Mike Vogel Secretary By Dennis L. Noble Brian Deans Member U.S. LIGHTHOUSE SOCIETY DEPARTMENTS Tim Blackwood Member Ralph Eshelman Member Notice to Keepers 68 Ken Smith Member Thomas A. Tag Member THE KEEPER’S LOG STAFF Head Keep’—Wayne C. Wheeler Editor—Jeffrey S. Gales Production Editor and Graphic Design—Marie Vincent Copy Editor—Dick Richardson Technical Advisor—Thomas Tag The Keeper’s Log (ISSN 0883-0061) is published quarterly for $40 per year by the U.S. -

National Historic Landmark Nomination Cape Ann Light

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CAPE ANN LIGHT STATION (Thacher Island Twin Lights) Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Cape Ann Light Station Other Name/Site Number: Thacher Island Twin Lights 2. LOCATION Street & Number: One mile off coast of Rockport, Massachusetts. Not for publication: City/Town: Rockport Vicinity: X State: MA County: Essex Code: 009 Zip Code: 01966 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: Building(s): Public-Local: X District: X Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 4 buildings sites 2 2 structures objects 6 2 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 6 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: n/a (see summary context statement for Lighthouse NHL theme study) NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CAPE ANN LIGHT STATION (Thacher Island Twin Lights) Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Lighthouse Bibliography.Pdf

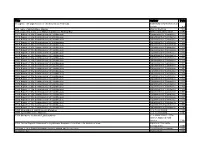

Title Author Date 10 Lights: The Lighthouses of the Keweenaw Peninsula Keweenaw County Historical Society n.d. 100 Years of British Glass Making Chance Brothers 1924 137 Steps: The Story of St Mary's Lighthouse Whitley Bay North Tyneside Council 1999 1911 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1911 1912 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1912 1913 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1913 1914 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1914 1915 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1915 1916 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1916 1917 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1917 1918 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1918 1919 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1919 1920 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1920 1921 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1921 1922 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1922 1923 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1923 1924 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1924 1925 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1925 1926 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1926 1927 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1927 1928 Report of the Commissioner of -

Trip Planner U.S

National Park Service Trip Planner U.S. Department of the Interior Cape Cod National Seashore Seasonal listings of activities, events, and ranger programs are available at seashore visitor centers. NPS/MCQUEENEY Park Information Superintendent’s Message Cape Cod National Seashore Oversand Office at Race Point Mention Cape Cod National 99 Marconi Site Road Ranger Station Seashore and different thoughts Wellfleet, MA 02667 Route Information: come to mind. Certainly, for Superintendent: Brian Carlstrom 508-487-2100, ext. 0926 many, the national seashore is Email: [email protected] (April 15 through November 15) “the beach”—a place to recreate, rejuvenate, and forge lasting Park Headquarters, Wellfleet Permit Information: memories with family and friends. 508-771-2144 508-487-2100, ext. 0927 Other people are attracted to Fax: 508-349-9052 nature’s wildness. Change is an North Atlantic Coastal Lab ever-present force on the Outer Nauset Ranger Station, Eastham 508-487-3262 Cape, with wind, waves, and 508-255-2112 storms constantly shaping and reshaping the land. As the longest Emergencies: 911 NPS/KEKOA ROSEHILL Race Point Ranger Station, Provincetown continuous stretch of shoreline 508-487-2100 https://www.nps.gov/caco on the East Coast, the national seashore doesn’t just host sun-loving humans; it provides a refuge Salt Pond Visitor Center Province Lands Visitor Center for many species, including threatened shorebirds. Salt marshes and forests support a diverse array of plants and animals. And off-shore, Open daily from 9 am to 4:30 pm (later during Open daily from 9 am to 5 pm, mid-April to the ocean teems with life, including the microscopic plankton that the summer). -

97492Main Cacomap1.Pdf

Race Point Beach National Park Service Old Harbor Life-Saving Station Museum 0 1 2 Kilometers R a T ce 1 2 Miles IN 0 PO Province Lands E C North A Visitor Center R Provincetown Po Muncipal in (seasonal) Race Airport Road t A D S ut Point HatchesHatches ik A h e s N o Light HarborHarbor d D ri n R ze a o D T d L P Beech Forest Trail a U o H d N r N e w E o T a rr S t in v o n io i g w n n C o a c n o f l e e v S c T o e n t ea i r o v f o u s r P w h 6 r o A TLANTIC OCEAN o Clapps n re Pond Street B ou Pilgrim 6A P nd A a Herring Monument R r A y Cove and Provincetown Museum D B PROVINCETOWN U O rd N L Beach fo E IC d Pilgrim Lake S National Park Service ra B U.S.-Coast Guard Station (East Harbor) 6A B e a c h H h ig e P H a o h d g d snack bar in i a P R O V I N C E T O W N t H e d H A R B O R a Pilgrim Heights (seasonal) H o R Sa Small’s lt Swamp M ea Dike Trail Pilgrim do Submerged Spring w at extreme Trail National Park Service high tide. -

Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound

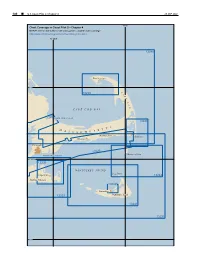

186 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 26 SEP 2021 70°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 2—Chapter 4 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 70°30'W 13246 Provincetown 42°N C 13249 A P E C O D CAPE COD BAY 13229 CAPE COD CANAL 13248 T S M E T A S S A C H U S Harwich Port Chatham Hyannis Falmouth 13229 Monomoy Point VINEYARD SOUND 41°30'N 13238 NANTUCKET SOUND Great Point Edgartown 13244 Martha’s Vineyard 13242 Nantucket 13233 Nantucket Island 13241 13237 41°N 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 ¢ 187 Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound (1) This chapter describes the outer shore of Cape Cod rapidly, the strength of flood or ebb occurring about 2 and Nantucket Sound including Nantucket Island and the hours later off Nauset Beach Light than off Chatham southern and eastern shores of Martha’s Vineyard. Also Light. described are Nantucket Harbor, Edgartown Harbor and (11) the other numerous fishing and yachting centers along the North Atlantic right whales southern shore of Cape Cod bordering Nantucket Sound. (12) Federally designated critical habitat for the (2) endangered North Atlantic right whale lies within Cape COLREGS Demarcation Lines Cod Bay (See 50 CFR 226.101 and 226.203, chapter 2, (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are for habitat boundary). It is illegal to approach closer than described in 33 CFR 80.135 and 80.145, chapter 2. -

BOSTON LIGHT: 304 YEARS of SERVICE UNITED STATES COAST GUARD Division Commanders 2020

Nor’Easter First District Northern Region Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island SUMMER 2020 BOSTON LIGHT: 304 YEARS OF SERVICE UNITED STATES COAST GUARD Division Commanders 2020 District Commander Division 1 Harold Frederick Herman RDML Thomas G. Allan, Jr. Division 2 John Robert Byrne Division 3 James S. Crocker Chief of Prevention Division 4 John Alan Flanagan CAPT Richard Schultz Division 5 Irwin M. Cohen Division 6 Arnold Mark Geller Director of Auxiliary District 1NR Division 7 Marcus Paul Mitchell CDR Christina D. Sullivan Division 9 Charles Irvin Motes, Jr. Division 10 Mary Bentley Operations Training Officer Division 11 Dennis Ray Bunnell BOSN 2 Elijah Reynolds Division 12 Kevin P. Ritchie U.S. COAST GUARD AUXILIARY District Staff Officers District Commodore Prevention Department COMO Charles B. Grossimon Harlan M. Doliner DSO-MS Donald B. Ladd, Jr. DSO-MT District Chief of Staff Frank J. Larkin DSO-NS Byron A. Moe, Jr. Lance John McNally DSO-PE Immediate Past District Commodore Raymond C. Julian DSO-PV COMO Philip J. Kubat Robert Harold Amiro DSO-VE District Captain North Response Department John W. Hume Carl D. England, Jr. DSO-AV David Ernest Clinton DSO-CM District Captain Boston Joseph J. Hogan DSO-OP Glen Alan Gayton Logistics Department District Captain South William J. Bell DSO-CS David G. McClure Carolyn E. McClure DSO-FS Dewayne R. Roos DSO-HR Auxiliary Sector Coordinators Laurel J. Carlson DSO-IS Stephen C. McCann DSO-PA ASC Sector Northern New England Wesley M. Baden DSO-PB James Malcolm Maxner Allen R. Padwa DSO-SR Richard Bruce Brady DSO-DV ASC Sector Boston Jason Oliveira DSO-AS James B. -

The Dukes County Intelligencer, Summer 2014

Journal of History of Martha’s Vineyard and the Elizabeth Islands THE DUKES COUNTY INTELLIGENCER VOL. 55, NO. 2 SUMMER 2014 Laura’s Lights: A Talk on Lighthouses From Spring, 1938 — In a Bygone Era of Information, Improvement & Sociability The Invasion: Rehearsal for D-Day Island Anomaly: The Unique Christianization Of Martha’s Vineyard Membership Dues Student ..........................................$25 Individual .....................................$55 (Does not include spouse) Family............................................$75 Sustaining ...................................$125 Patron ..........................................$250 Benefactor...................................$500 President’s Circle .....................$1,000 Memberships are tax deductible. For more information on membership levels and benefits, please visit www.mvmuseum.org To Our Readers omething old, something new, something borrowed. This edition of Sthe Dukes County Intelligencer makes me think of that little ditty and the marvelous marriage there is between the Museum and the island. For our something old, we have a transcript of a speech given to sev- eral Island ladies’ clubs by Laura G. Vincent in the mid-1930s. Vincent, an aunt of longtime Museum volunteer Peg Kelley, was the daughter of Charles Macreading Vincent, whose Civil War letters home were lovingly transcribed by former Museum director Marian Halperin and published in 2008 as Your Affectionate Son, Charlie Mac: Civil War Diaries and Let- ters by a Soldier from Martha’s Vineyard. ‘Borrowed’ is an excerpt from Martha’s Vineyard in World War II by frequent contributor Tom Dresser and his writing partners Herb Foster and Jay Schofield. Their new book, published by History Press, features a forward by the Museum’s oral history curator, Linsey Lee. Lastly, our something new is a research paper written by former Mu- seum intern Tara Keegan for her class on Colonial America regarding the conversion of Island Wampanoags to Christianity.