Keeping Lighthouses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northeast Harbor Library Archives GXS Collection Finding Aid

Northeast Harbor Library Archives GXS Collection Finding Aid Creator: Anonymous collector Dates: 1800s and 1900s Extent: 1 linear foot Accession Number: 2016.6.1 Record Numbers: None. Collection Processed by: Hannah Stevens Scope and Content Note: This collection is an assortment of ephemera relating to coastal Maine, Maine history, and inns, motels, hotels, and homes on Mount Desert Island and Hancock County. The collection is divided into 7 series: Books and Souvenir Booklets, Maps and Blueprints, Acadia National Park, Hotels/Inns/Schools/Homes/Buildings, Ephemera, Photos and Postcards. Note: this collection will continue to be added to as we make space in the archive room. Source of Acquisition: Donated by anonymous donor via Willie Granston as proxy, June 2016. Access Restrictions: This collection is open to research. The collection is subject to all copyright laws. Biographical Information: None. Box 1 Books and Souvenir Booklets Folder 1 Glimpses of Camden, Maine, 1904, J. R. Prescott, 28 pages Glimpses of Camden On the Coast of Maine, 1916, John R. Prescott, 1 volume (unpaged): all illustrations Folder 2 A Souvenir of Bar Harbor and Mount Desert Island, Maine, 190?, W. H. Sherman, 68 pages : chiefly illustrations Folder 3 Bar Harbor and Mount Desert Island, 1888, William Berry Lapham, 72 pages: illustrations Folder 4 unidentified book about Maine homes and churches in the early days, commentary about home design, coastal living, farming, and general livelihood. 32 pages missing covers. Folder 5 The Summer State of Maine, Holman D Waldron and Harry D Young, ca. 1893, Tourist booklet in the shape of the state of Maine; cover illustration is map of Maine, 24 pages Folder 31 Looking at Katahdin, the artists' inspiration, booklet about exhibit at L.C. -

Beacons of the Coast

National Seashore National Park Service Cape Lookout U.S. Department of the Inerior Beacons of the Coast Over a century ago, mariners travelling along the Atlantic coast encountered dangerous shoals and treacherous storms. Their guides were the beacons of light produced by lighthouses which helped mariners navigate the perilous coastline. For mariners traveling along the North Carolina coast, seven lighthouse beacons were constructed to guide them through an area known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic.” Hundreds of shipwrecks occurred due to the dangers of this area. Today, the ships traveling the coast use modern tools such as radar and sonar. The beacons continue to operate, standing as a reminder of the hardships encountered by our ancestors to help settle the country. These seven lighthouses found on the North Carolina coast stand as pieces of our past. CURRITUCK BEACH LIGHTHOUSE This lighthouse was constructed from 1874 - 1875, and it lit the last dark spot on the Carolina coast between the Cape Fear lighthouse in Virginia and Bodie Island. The red brick lighthouse rises 158 feet above sea level. Unlike many other lighthouses that received distinctive day marks, Currituck was not painted. But its red brick is unique on the Carolina coast. It has a short light signal: 5 seconds on, 15 seconds off. There is a Fresnel lens still working in the lighthouse and it is activated from dusk to dawn. Currituck Lighthouse is open 10-6 daily from Easter to Thanksgiving weekend. You can walk to the top of the lighthouse. BODIE ISLAND LIGHTHOUSE This was the third lighthouse to be built on Bodie Island (pronounced “body”) and was constructed in the early 1870’s. -

Growing up in the Old Point Loma Lighthouse (Teacher Packet)

Growing Up in the Old Point Loma Lighthouse Teacher Packet Program: A second grade program about living in the Old Point Loma Lighthouse during the late 1800s, with emphasis on the lives and activities of children. Capacity: Thirty-five students. One adult per five students. Time: One hour. Park Theme to be Interpreted: The Old Point Loma Lighthouse at Cabrillo National Monument has a unique history related to San Diego History. Objectives: At the completion of this program, students will be able to: 1. List two responsibilities children often perform as a family member today. 2. List two items often found in the homes of yesterday that are not used today. 3. State how the lack of water made the lives of the lighthouse family different from our lives today. 4. Identify two ways lighthouses help ships. History/Social Science Content Standards for California Grades K-12 Grade 2: 2.1 Students differentiate between things that happened long ago and things that happened yesterday. 1. Trace the history of a family through the use of primary and secondary sources, including artifacts, photographs, interviews, and documents. 2. Compare and contrast their daily lives with those of their parents, grandparents, and / or guardians. Meeting Locations and Times: 9:45 a.m. - Meet the ranger at the planter in front of the administration building. 11:00 a.m. - Meet the ranger at the garden area by the lighthouse. Introduction: The Old Point Loma Lighthouse was one of the eight original lighthouses commissioned by Congress for service on the West Coast of the United States. -

On the Road Again ... Heading North

Newsletter of The Delaware Bay Lighthouse Keepers and Friends Association, Inc. Volume 37 Issue 16 “Our mission is to preserve the history of the Winter 2018 Delaware Bay and River Lighthouses, Lightships and their Keepers” ON THE ROAD AGAIN ... HEADING NORTH Having never been to the Eastern Maritime Provinces of Canada, we decided to sign up for a nine day bus tour of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. After traveling north and going through customs, we crossed the US/Canadian border at Calais, Maine. Moving our watches one hour ahead to Atlantic Daylight Saving Time, we proceeded to the Hilton Hotel in St. John, New Brunswick. Our hotel was located on the Bay of Fundy noted for its drastic tide changes. The tide ebbs or rises one foot every 15 minutes. Another feature of this Bay is the “reverse falls;” when the tide ebbs, the water flows UP the falls…strange indeed. Two of New Brunswick’s earliest recorded lighthouses are both located on the Bay of Fundy. One, Campobello Island Light (a), was constructed on the island where President Franklin Roosevelt spent his summers. This lighthouse is accessible on foot only at low tide. The other located on the Bay of Fundy is the eight meter tall Cape Enrage Light built in 1848. The majority of Canadian lighthouses are red and white so they can easily be seen during the heavy winter snowstorms. New Brunswick boasts of over 90 lighthouses. We crossed from St. John, NB to Digby, Nova Scotia by ferry and continued on to Wolfville, NS. -

U.S. Lake Erie Lighthouses

U.S. Lake Erie Lighthouses Gretchen S. Curtis Lakeside, Ohio July 2011 U.S. Lighthouse Organizations • Original Light House Service 1789 – 1851 • Quasi-military Light House Board 1851 – 1910 • Light House Service under the Department of Commerce 1910 – 1939 • Final incorporation of the service into the U.S. Coast Guard in 1939. In the beginning… Lighthouse Architects & Contractors • Starting in the 1790s, contractors bid on LH construction projects advertised in local newspapers. • Bids reviewed by regional Superintendent of Lighthouses, a political appointee, who informed U.S. Treasury Dept of his selection. • Superintendent approved final contract and supervised contractor during building process. Creation of Lighthouse Board • Effective in 1852, U.S. Lighthouse Board assumed all duties related to navigational aids. • U.S. divided into 12 LH districts with inspector (naval officer) assigned to each district. • New LH construction supervised by district inspector with primary focus on quality over cost, resulting in greater LH longevity. • Soon, an engineer (army officer) was assigned to each district to oversee construction & maintenance of lights. Lighthouse Bd Responsibilities • Location of new / replacement lighthouses • Appointment of district inspectors, engineers and specific LH keepers • Oversight of light-vessels of Light-House Service • Establishment of detailed rules of operation for light-vessels and light-houses and creation of rules manual. “The Light-Houses of the United States” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Dec 1873 – May 1874 … “The Light-house Board carries on and provides for an infinite number of details, many of them petty, but none unimportant.” “The Light-Houses of the United States” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Dec 1873 – May 1874 “There is a printed book of 152 pages specially devoted to instructions and directions to light-keepers. -

The Oldest Lighthouse 1

The Oldest Lighthouse 1 The Oldest Lighthouse Ken Trethewey1 Fig. 1: The Pharos at Dover, built around the 2nd c. BCE., is a candidate for the oldest existing lighthouse. Introduction harologists are frequently asked, What is the oldest A light marking the tomb of Achilles at Sigeum in the Plighthouse? The answer is, of course, difficult to Hellespont has frequently been proposed. Its location answer without further qualification. Different people at the entrance to the strategic route between the might argue over the definition of a lighthouse, for Mediterranean and Black Seas would have created example.2 Others might be asking about the first a vital navigational aid as long ago as the twelfth or lighthouse that was ever built. A third group might be thirteenth centuries BCE. This could have inspired ideas asking for the oldest lighthouse they can see right now. of lighthouses, even if its form was inconsistent with All of these questions have been dealt with in detail our traditional designs. In later centuries (though still in my recent publication.3 The paper that follows is an prior to the building of the Alexandrian Pharos) Greeks overview of the subject for the casual reader. seem to have been using small stone towers with fires on top (Figs. 3, 4 and 5) to indicate the approaches Ancient Lighthouses to ports in the Aegean. Thus, however the idea was actually conceived, the Greeks can legitimately claim to Most commonly the answer given to questions have inspired an aid to navigation that has been of great about the oldest lighthouse has been the Pharos at value to mariners right up to the present day. -

Fire Island Light Station

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES--COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Fire Island Light Station _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN Bay Shore 0.1. STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New York 36 Suffolk HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT -XPUBLIC OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) ^.PRIVATE X.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL XPARK _XSTRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _ IN PROCESS iLYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) National Park Service, Morth Atlantic Region STREET & NUMBER 15 State Street CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF Massachusetts COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Land Acquisition Division, National Park Service, North Atlantic CITY. TOWN STATE Boston, Massachusetts TITLE U.S. Coast Guard, 3d Dist., "Fire Island Station Annex" Civil Plot Plan 03-5523 DATE 18 June 1975, revised 8-7-80 .^FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS- Nationa-| park Service, North Atlantic Regional Office CITY, TOWN CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD _RUINS . X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE_____ X.FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Fire Island Light Station is situated 5 miles east of the western end of Fire Island, a barrier island off the southern coast of Long Island. It consists of a lighthouse and an adjacent keeper's quarters sitting on a raised terrace. -

National Register of Historic Places

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES IN HANCOCK COUNTY, MAINE PLACE NAME STREET ADDRESS TOWN BRICK SCHOOL HOUSE SCHOOL HOUSE HILL AURORA TURRETS, THE EDEN STREET BAR HARBOR REDWOOD BARBERRY LANE BAR HARBOR HIGHSEAS SCHOONER HEAD ROAD BAR HARBOR CARRIAGE PATHS, BRIDGES AND GATEHOUSES ACADIA NATIONAL PARK+VICINITY BAR HARBOR EEGONOS 145 EDEN STREET BAR HARBOR CRITERION THEATRE 35 COTTAGE STREET BAR HARBOR WEST STREET HISTORIC DISTRICT WEST BET BILLINGS AVE+ EDEN ST BAR HARBOR SPROUL'S CAFE 128 MAIN STREET BAR HARBOR REVERIE COVE HARBORLANE BAR HARBOR ABBE, ROBERT, MUSEUM OF STONE AGE ANTIQUITY OFF ME 3 BAR HARBOR "NANAU" LOWER MAIN STREET BAR HARBOR JESUP MEMORIAL LIBRARY 34 MT DESERT ROAD BAR HARBOR KANE, JOHN INNES, COTTAGE OFF HANCOCK STREET BAR HARBOR US POST OFFICE - BAR HARBOR MAIN COTTAGE STREET BAR HARBOR SAINT SAVIOUR'S EPISCOPAL CHURCH & RECTORY 41 MT DESERT STREET BAR HARBOR COVER FARM OFF ME 3 (HULLS COVE) BAR HARBOR (FORMER) ST EDWARDS CONVENT 33 LEDGELAWN AVENUE BAR HARBOR HULLS COVE SCHOOL HOUSE CROOK ROAD & ROUTE 3 BAR HARBOR CHURCH OF OUR FATHER ME ROUTE 3 BAR HARBOR CLEFTSTONE 92 EDEN STREET BAR HARBOR STONE BARN FARM CROOKED RD AT NORWAY DRIVE BAR HARBOR FISHER, JONATHAN, MEMORIAL ME 15 (OUTER MAIN STREET) BLUE HILL HINCKLEY, WARD, HOUSE ADDRESS RESTRICTED BLUE HILL BARNCASTLE SOUTH STREET BLUE HILL BLUE HILL HISTORIC DISTRICT ME 15, ME 172, ME 176 & ME 177 BLUE HILL PETERS, JOHN, HOUSE OFF ME 176 BLUE HILL EAST BLUE HILL LIBRARY MILLIKEN ROAD BLUE HILL GODDARD SITE ADDRESS RESTRICTED BROOKLIN BROOKLIN IOOF HALL SR 175 -

Sandy Hook Lighthouse. the Facts, Mystery and History Surrounding

National Park Service Gateway National Recreation Area U.S. Department of the Interior Sandy Hook Unit Sandy Hook Lighthouse The Facts, Mystery and History Surrounding America’s Oldest Operating Lighthouse Talk about “All in the Family”: Keeper Charles W. Patterson was in charge of Sandy Hook Lighthouse for 24 years. He had four brothers who served in the union army during the Civil War. Charles also tried to enlist in the army but was turned down for medical reasons. He then applied for an appointment to become a lighthouse keeper and was appointed keeper of Sandy Hook Lighthouse in 1861. Charles probably helped his sister, Sarah Patterson Johnson, get the job of Assistant Keeper at Sandy Hook Lighthouse, who was appointed in 1867. Sarah later resigned her position to become a public school teacher at the Sandy Hook Proving Ground. Sarah was replaced as assistant keeper by Samuel P. Jewell, who was married to Emma Patterson Megill, who was related to Charles W. Patterson. Another relative working at Sandy Hook related to Charles was Trevonian H. Patterson, who was Sandy Hook Lighthouse & Keepers Quarters, located in the Fort Hancock area of the park. described in an 1879 article as having “lived at Sandy Hook since he was one year old, second lighthouse, after the Statue of in the New York Sun newspaper, dated knows every inch of the beach [at Sandy Liberty, to be lighted by electricity. Then, April 18, 1909, announced that Jewell “Quits Hook], and is as familiar with [all the] on May 9, 1896, Jewell would also witness Sandy Hook Light.” -

Received Dec 71987

NPS Form 10*00 OMB Mo. f 02440I« (ftov. M8) United States Department of the Interior RECEIVED National Park Service DEC 71987, NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines tor Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information, tf an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form I0-90pa). Type al entries. 1. Name of Property historic name Fort Point Liqht Station other names/site number 2. Location street & number Fort Point Road N/ '1i. not for publication city, town Stockton Springs , 3L vicinity state Maine code ME county Waldo code 027 zip code 04981 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property private building(s) Contributing public-local X district 3___ public-State site X public-Federal structure 1 object 4 Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously Liqht Stations of Maine listed in the National Register _Q______ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this 0 nomination ED request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

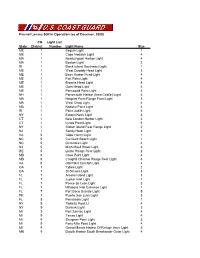

Fresnel Lenses Still in Operation (As of Decemer, 2008) State CG District

Fresnel Lenses Still in Operation (as of Decemer, 2008) CG Light List State District Number Light Name Size ME 1 Seguin Light 1 ME 1 Cape Neddick Light 4 MA 1 Newburyport Harbor Light 4 MA 1 Boston Light 2 RI 1 Block Island Southeast Light 1 ME 1 West Quoddy Head Light 3 ME 1 Bass Harbor Head Light 4 ME 1 Fort Point Light 4 ME 1 Browns Head Light 4 ME 1 Owls Head Light 4 ME 1 Pemaquid Point Light 4 NH 1 Portsmouth Harbor (New Castle) Light 4 MA 1 Hospital Point Range Front Light 3 MA 1 West Chop Light 4 MA 1 Nobska Point Light 4 RI 1 Point Judith Light 4 NY 1 Eatons Neck Light 3 CT 1 New London Harbor Light 4 CT 1 Lynde Point Light 5 NY 1 Staten Island Rear Range Light 2 NJ 1 Sandy Hook Light 3 VA 5 Cape Henry Light 1 NC 5 Currituck Beach Light 1 NC 5 Ocracoke Light 4 NJ 5 Miah Maull Shoal Light 4 DE 5 Liston Range Rear Light 2 MD 5 Cove Point Light 4 MD 5 Craighill Channel Range Rear Light 4 VA 5 Old Point Comfort Light 4 GA 7 Tybee Light 2 GA 7 St Simons Light 3 FL 7 Amelia Island Light 3 FL 7 Jupiter Inlet Light 1 FL 7 Ponce de Leon Light 3 FL 7 Hillsboro Inlet Entrance Light 1 FL 7 Port Boca Grande Light 5 PR 7 Puerto San Juan Light 3 FL 8 Pensacola Light 1 NY 9 Tibbetts Point Lt 4 NY 9 Dunkirk Light 3 MI 9 Port Sanilac Light 4 MI 9 Tawas Light 4 MI 9 Sturgeon Point Light 3 MI 9 Forty-Mile Point Light 4 MI 9 Grand Marais Harbor Of Refuge Inner Light 5 MN 9 Duluth Harbor South Breakwater Outer Light 4 CG Light List State District Number Light Name Size MN 9 Duluth Harbor North Pier Light 5 MN 9 Grand Marais Light 5 MI 9 St James Light -

Final 2012 NHLPA Report Noapxb.Pub

GSA Office of Real Property Utilization and Disposal 2012 PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS REPORT NATIONAL HISTORIC LIGHTHOUSE PRESERVATION ACT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lighthouses have played an important role in America’s For More Information history, serving as navigational aids as well as symbols of our rich cultural past. Congress passed the National Information about specific light stations in the Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act (NHLPA) in 2000 to NHLPA program is available in the appendices and establish a lighthouse preservation program that at the following websites: recognizes the cultural, recreational, and educational National Park Service Lighthouse Heritage: value of these iconic properties, especially for local http://www.nps.gov/history/maritime/lt_index.htm coastal communities and nonprofit organizations as stewards of maritime history. National Park Service Inventory of Historic Light Stations: http://www.nps.gov/maritime/ltsum.htm Under the NHLPA, historic lighthouses and light stations (lights) are made available for transfer at no cost to Federal agencies, state and local governments, and non-profit organizations (i.e., stewardship transfers). The NHLPA Progress To Date: NHLPA program brings a significant and meaningful opportunity to local communities to preserve their Since the NHLPA program’s inception in 2000, 92 lights maritime heritage. The program also provides have been transferred to eligible entities. Sixty-five substantial cost savings to the United States Coast percent of the transferred lights (60 lights) have been Guard (USCG) since the historic structures, expensive to conveyed through stewardship transfers to interested repair and maintain, are no longer needed by the USCG government or not-for-profit organizations, while 35 to meet its mission as aids to navigation.