Sustainable Development Goals: Agenda 2030 INDIA 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India's Largest Rural Sanitation Survey For

INDIA’S LARGEST RURAL SANITATION SURVEY FOR RANKING OF STATES AND DISTRICTS Page 1 of 80 PREFACE The “Swachh Survekshan Grameen – 2018” was commissioned by the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation, through an independent survey agency. One month long survey, ranked all districts and states of India on the basis of quantitative and qualitative sanitation (Swachhta) parameters, towards their sanitation and cleanliness status. As part of Swachh Survekshan Grameen, 6867 villages in 685 Districts across India were covered. 34,000 public places namely schools, anganwadis, public health centres, haat-bazaars, religious places in these 6867 villages were visited to be surveyed. Around 1,62,000 citizens were interviewed in villages, for their feedback on issues related to the Swachh Bharat Mission. Citizens were also encouraged to provide online feedback on sanitation relation related issues. Feedback from collectives was obtained using community wide open meetings (khuli baithaks), personal interviews and Group Discussions (GDs). GDs were conducted in each village. More than 1.5 crore people participated in the SSG-2018 and provided their feedback. The SSG turned out to be massive mobilisation exercise with communities in each village undertaking special drives to improve the general cleanliness in their villages. Gram Panchayats invested funds from their local area development fund to improve the sanitation status in public places. The Ministry is encouraged with the overall outcomes of Swachh Survekshan Grameen 2018 and would like to institutionalise this for concurrent ranking of states and districts and obtaining citizens feedback. (Uma Bharti) MESSAGE Swachh Survekshan Grameen – 2018, launched on 13 July 2018, is a maiden attempt by Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation (MDWS) to rank states and districts on key sanitation parameters. -

URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE Analysis of Urban Infrastructure Interventions, Vijayawada City, Andhra

URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE Analysis of Urban Infrastructure Interventions, Vijayawada City, Andhra Cost-Benefit Analysis AUTHORS: Parijat Dey O Rajesh Babu Senior Manager Assistant Vice President IL&FS APUIAML © 2018 Copenhagen Consensus Center [email protected] www.copenhagenconsensus.com This work has been produced as a part of the Andhra Pradesh Priorities project under the larger, India Consensus project. This project is undertaken in partnership with Tata Trusts. Some rights reserved This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution Please cite the work as follows: #AUTHOR NAME#, #PAPER TITLE#, Andhra Pradesh Priorities, Copenhagen Consensus Center, 2017. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0. Third-party-content Copenhagen Consensus Center does not necessarily own each component of the content contained within the work. If you wish to re-use a component of the work, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that re-use and to obtain permission from the copyright owner. Examples of components can include, but are not limited to, tables, figures, or images. Cost Benefit Analysis of Urban Infrastructure Interventions, Vijayawada City, Andhra Pradesh Andhra Pradesh Priorities An India Consensus Prioritization Project Parijat Dey1, O Rajesh Babu2 1Senior -

Trends in Bidi and Cigarette Smoking in India from 1998 to 2015, by Age, Gender and Education

Research Trends in bidi and cigarette smoking in India from 1998 to 2015, by age, gender and education Sujata Mishra,1 Renu Ann Joseph,1 Prakash C Gupta,2 Brendon Pezzack,1 Faujdar Ram,3 Dhirendra N Sinha,4 Rajesh Dikshit,5 Jayadeep Patra,1 Prabhat Jha1 To cite: Mishra S, ABSTRACT et al Key questions Joseph RA, Gupta PC, . Objectives: Smoking of cigarettes or bidis (small, Trends in bidi and cigarette locally manufactured smoked tobacco) in India has smoking in India from 1998 What is already known about this topic? likely changed over the last decade. We sought to to 2015, by age, gender and ▸ India has over 100 million adult smokers, the education. BMJ Global Health document trends in smoking prevalence among second highest number of smokers in the world – 2016;1:e000005. Indians aged 15 69 years between 1998 and 2015. after China. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2015- Design: Comparison of 3 nationally representative ▸ There are already about 1 million adult deaths 000005 surveys representing 99% of India’s population; the per year from smoking. Special Fertility and Mortality Survey (1998), the Sample Registration System Baseline Survey (2004) What are the new findings? and the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (2010). ▸ The age-standardised prevalence of smoking Setting: India. declined modestly among men aged 15–69 years, ▸ Additional material is Participants: About 14 million residents from 2.5 but the absolute number of male smokers at these published online only. To million homes, representative of India. ages grew from 79 million in 1998 to 108 million view please visit the journal in 2015. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-19605-6 — Boundaries of Belonging Sarah Ansari , William Gould Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-19605-6 — Boundaries of Belonging Sarah Ansari , William Gould Index More Information Index 18th Amendment, 280 All-India Muslim Ladies’ Conference, 183 All-India Radio, 159 Aam Aadmi (Ordinary Man) Party, 273 All-India Refugee Association, 87–88 abducted women, 1–2, 12, 202, 204, 206 All-India Refugee Conference, 88 abwab, 251 All-India Save the Children Committee, Acid Control and Acid Crime Prevention 200–201 Act, 2011, 279 All-India Scheduled Castes Federation, 241 Adityanath, Yogi, 281 All-India Women’s Conference, 183–185, adivasis, 9, 200, 239, 261, 263, 266–267, 190–191, 193–202 286 All-India Women’s Food Council, 128 Administration of Evacuee Property Act, All-Pakistan Barbers’ Association, 120 1950, 93 All-Pakistan Confederation of Labour, 256 Administration of Evacuee Property All-Pakistan Joint Refugees Council, 78 Amendment Bill, 1952, 93 All-Pakistan Minorities Alliance, 269 Administration of Evacuee Property Bill, All-Pakistan Women’s Association 1950, 230 (APWA), 121, 202–203, 208–210, administrative officers, 47, 49–50, 69, 101, 212, 214, 218, 276 122, 173, 176, 196, 237, 252 Alwa, Arshia, 215 suspicions surrounding, 99–101 Ambedkar, B.R., 159, 185, 198, 240, 246, affirmative action, 265 257, 262, 267 Aga Khan, 212 Anandpur Sahib, 1–2 Agra, 128, 187, 233 Andhra Pradesh, 161, 195 Ahmad, Iqbal, 233 Anjuman Muhajir Khawateen, 218 Ahmad, Maulana Bashir, 233 Anjuman-i Khawateen-i Islam, 183 Ahmadis, 210, 268 Anjuman-i Tahafuuz Huqooq-i Niswan, Ahmed, Begum Anwar Ghulam, 212–213, 216 215, 220 -

Trends in Bidi and Cigarette Smoking in India from 1998 to 2015, by Age, Gender and Education

Research BMJ Glob Health: first published as 10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000005 on 6 April 2016. Downloaded from Trends in bidi and cigarette smoking in India from 1998 to 2015, by age, gender and education Sujata Mishra,1 Renu Ann Joseph,1 Prakash C Gupta,2 Brendon Pezzack,1 Faujdar Ram,3 Dhirendra N Sinha,4 Rajesh Dikshit,5 Jayadeep Patra,1 Prabhat Jha1 To cite: Mishra S, ABSTRACT et al Key questions Joseph RA, Gupta PC, . Objectives: Smoking of cigarettes or bidis (small, Trends in bidi and cigarette locally manufactured smoked tobacco) in India has smoking in India from 1998 What is already known about this topic? likely changed over the last decade. We sought to to 2015, by age, gender and ▸ India has over 100 million adult smokers, the education. BMJ Global Health document trends in smoking prevalence among second highest number of smokers in the world – 2016;1:e000005. Indians aged 15 69 years between 1998 and 2015. after China. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2015- Design: Comparison of 3 nationally representative ▸ There are already about 1 million adult deaths 000005 surveys representing 99% of India’s population; the per year from smoking. Special Fertility and Mortality Survey (1998), the Sample Registration System Baseline Survey (2004) What are the new findings? and the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (2010). ▸ The age-standardised prevalence of smoking Setting: India. declined modestly among men aged 15–69 years, ▸ Additional material is Participants: About 14 million residents from 2.5 but the absolute number of male smokers at these published online only. To million homes, representative of India. -

Swachh Survekshan 2020: Mohua

Swachh Survekshan 2020: MoHUA drishtiias.com/printpdf/swachh-survekshan-2020-mogua Why in News Recently, the Swachh Survekshan 2020 report has been launched by the Union Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA). It is the fifth edition of the annual cleanliness urban survey conducted by the MoHUA. It is one of the world’s largest sanitation surveys. Key Points This year the Ministry has released rankings based on the categorisation of cities on population, instead of releasing overall rankings. The categories based on population were introduced in 2019 for the first time but the exact groupings have been changed this year. 1/3 Major Categories and Rankings: Cities with a population of more than 10 lakh: Indore was ranked first, securing the rank for the fourth consecutive year, followed by Surat and Navi Mumbai. All the National Capital Region (NCR) cities, Greater Mumbai, Bruhat Bengaluru, Amritsar, Kota, Chennai, etc. have performed poorly. Patna with the rank 47, is at the bottom of the list. Cities with a population of 1-10 lakh: Chhattisgarh’s Ambikapur has been surveyed as the cleanest city in the country, followed by Mysore and New Delhi. Bihar’s Gaya with a rank of 382, is at the bottom. Cities with a population of less than 1 lakh: Karad has been ranked as the cleanest followed by Sasvad and Lonavala (all three in Maharashtra). Other Categories: Varanasi has been ranked the cleanest among 46 Ganga towns. Jalandhar got the top rank among cantonments. New Delhi was the cleanest capital city. Chhattisgarh was ranked the cleanest State out of those with over 100 urban local bodies (ULBs) or cities. -

Prostitutes, Eunuchs and the Limits of the State Child “Rescue” Mission in Colonial India

9. Deviant Domesticities and Sexualised Childhoods: Prostitutes, Eunuchs and the Limits of the State Child “Rescue” Mission in Colonial India Jessica Hinchy Nanyang Technological University, Singapore Introduction In the late 1860s and early 1870s, colonial officials in north India argued that the British government had a duty to “rescue” girls and boys who were allegedly kidnapped and condemned to a “life of infamy” by eunuchs and women labelled prostitutes. Colonial officials claimed that prostitutes and eunuchs sexually “corrupted” girls and boys, respectively, and hired them out as child prostitutes. British administrators proposed to register and remove children who resided with prostitutes and eunuchs and to appoint “respectable” guardians. In India, unlike Australia, the removal of children was not a general technique of colonial governance.1 These projects for the removal and reform of children who lived in brothels and with eunuchs were thus somewhat unusual colonial attempts at child rescue.2 The singular English-language colonial category of “eunuch” was internally diverse and encompassed a multiplicity of social roles. The term eunuch could be used to variously encapsulate male-identified and female-identified, emasculated and non-emasculated, socially elite and subaltern, politically powerful and relatively politically insignificant groups. Thehijra community 1 Satadru Sen, Colonial Childhoods: The Juvenile Periphery of India, 1850–1945, London: Anthem Press, 2005, p. 57. 2 The research for this paper was conducted at several archives in India, including the National Archives of India (NAI) in Delhi and the Uttar Pradesh State Archives (UPSA) branches in Lucknow and Allahabad. At the Allahabad branch of the Uttar Pradesh State Archives I was able to access district-level records on the implementation of the Criminal Tribes Act, Part II, against the hijra community, including the reports of local police intelligence and district registers of eunuchs’ personal details and property. -

American Indian Views of Smoking: Risk and Protective Factors

Volume 1, Issue 2 (December 2010) http://www.hawaii.edu/sswork/jivsw http://hdl.handle.net/10125/12527 E-ISSN 2151-349X pp. 1-18 ‘This Tobacco Has Always Been Here for Us,’ American Indian Views of Smoking: Risk and Protective Factors Sandra L. Momper Beth Glover Reed University of Michigan University of Michigan Mary Kate Dennis University of Michigan Abstract We utilized eight talking circles to elicit American Indian views of smoking on a U.S. reservation. We report on (1) the historical context of tobacco use among Ojibwe Indians; (2) risk factors that facilitate use: peer/parental smoking, acceptability/ availability of cigarettes; (3) cessation efforts/ inhibiting factors for cessation: smoking while pregnant, smoking to reduce stress , beliefs that cessation leads to debilitating withdrawals; and (4) protective factors that inhibit smoking initiation/ use: negative health effects of smoking, parental and familial smoking behaviors, encouragement from youth to quit smoking, positive health benefits, “cold turkey” quitting, prohibition of smoking in tribal buildings/homes. Smoking is prevalent, but protective behaviors are evident and can assist in designing culturally sensitive prevention, intervention and cessation programs. Key Words American Indians • Native Americans • Indigenous • tobacco • smoking • community based research Acknowledgments We would like to say thank you (Miigwetch) to all tribal members for their willingness to share their stories and work with us, and in particular, the Research Associate and Observer (Chi-Miigwetch). This investigation was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 DA007267 via the University of Michigan Substance Abuse Research Center (UMSARC). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or UMSARC. -

Sacred Smoking

FLORIDA’SBANNER INDIAN BANNER HERITAGE BANNER TRAIL •• BANNERPALEO-INDIAN BANNER ROCK BANNER ART? • • THE BANNER IMPORTANCE BANNER OF SALT american archaeologySUMMER 2014 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 18 No. 2 SACRED SMOKING $3.95 $3.95 SUMMER 2014 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 18 No. 2 COVER FEATURE 12 HOLY SMOKE ON BY DAVID MALAKOFF M A H Archaeologists are examining the pivitol role tobacco has played in Native American culture. HLEE AS 19 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF SALT BY TAMARA STEWART , PHOTO BY BY , PHOTO M By considering ethnographic evidence, researchers EU S have arrived at a new interpretation of archaeological data from the Verde Salt Mine, which speaks of the importance of salt to Native Americans. 25 ON THE TRAIL OF FLORIDA’S INDIAN HERITAGE TION, SOUTH FLORIDA MU TION, SOUTH FLORIDA C BY SUSAN LADIKA A trip through the Tampa Bay area reveals some of Florida’s rich history. ALLANT COLLE ALLANT T 25 33 ROCK ART REVELATIONS? BY ALEXANDRA WITZE Can rock art tell us as much about the first Americans as stone tools? 38 THE HERO TWINS IN THE MIMBRES REGION BY MARC THOMPSON, PATRICIA A. GILMAN, AND KRISTINA C. WYCKOFF Researchers believe the Mimbres people of the Southwest painted images from a Mesoamerican creation story on their pottery. 44 new acquisition A PRESERVATION COLLABORATION The Conservancy joins forces with several other preservation groups to save an ancient earthwork complex. 46 new acquisition SAVING UTAH’S PAST The Conservancy obtains two preserves in southern Utah. 48 point acquisition A TIME OF CONFLICT The Parkin phase of the Mississippian period was marked by warfare. -

Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS) for Rural Development in India

January, 2019 Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS) for Rural Development in India Participatory Research In Asia Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS) for Rural Development in India This is the consolidated data of CSS which elaborates on the details of the date of launch, purpose of the scheme and the concerned ministry or department responsible for the scheme. The provided links would help people to access details about each relevant scheme. Sl. Name of the Scheme Date of Purpose of the scheme Central Ministry/Department Source No. Launchin g 1. Accelerated Irrigation Benefits 1996-1997 To give loan assistance to the States to Department of Finance Accelerated Irrigation Programme (AIBP) help them complete some of the Benefits Programme. incomplete major/medium irrigation https://archive.india.gov.in/se projects which were at an advanced ctors/water_resources/index. stage of completion and to create php?id=8 additional irrigation potential in the country. 2. Ajeevika- National Rural Livelihood June. Mission aims at creating efficient and Panchayat & Rural Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana Mission(NRLM)- Swarn Jayanthi 2011 effective institutional platforms of the Development Department website. Link: Gram Swarojgar Yojana (SGSY) rural poor enabling them to increase https://aajeevika.gov.in/ HH income through sustainable livelihood enhancements and improved access to financial services. 3. Annapurna Scheme April. 2001 Old destitute who are not getting the Panchayat & Rural Annapurna Yojana. Link: National old age pension (NOAPS) but Development Department http://www.fcp.bih.nic.in/Anna have its eligibility, are being provided purna.htm 10 kg food-grain (6 kg wheat + 4 kg rice) per month free of cost as Food Security. -

Swachh Bharat Mission (S.B.M): a Step Towards Environmental Protection and Health Concerns

© 2021 JETIR July 2021, Volume 8, Issue 7 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) SWACHH BHARAT MISSION (S.B.M): A STEP TOWARDS ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AND HEALTH CONCERNS Dr.DHARMAVEER Research Supervisor Assistant Professor, Department of Commerce Sant Kavi Baba Baijnath Government P.G.College Harak, Barabanki (Affiliated to Dr.R.M.L.Awadh University, Ayodhya) NEHA SINGH Research Scholar, Department of Commerce Dr.R.M.L.Awadh University, Ayodhya (Under the Supervision of Dr.Dharmaveer) Dr MOHD NASEEM SIDDIQUI Life Member of I.S.C.A.Kolkata & Assistant Professor Department of Commerce. Mumtaz P.G.College,Lucknow (Associated to University of Lucknow) ABSTRACT Swachh Bharat Mission is a massive mass movement that seeks to create a Clean India by 2019. The father of our nation Mr. Mahatma Gandhi always puts the emphasis on swachhta as swachhta leads to healthy and prosperous life. Keeping this in mind, the Indian government has decided to launch the swachh bharat mission on October 2, 2014.The mission will cover all rural and urban areas. The urban component of the mission will be implemented by the Ministry of Urban Development, and the rural component by the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation. The programme includes elimination of open defecation, conversion of unsanitary toilets to pour flush toilets, eradication of manual scavenging, municipal solid waste management and bringing about a behavioural change in people regarding healthy sanitation practices.The mission aims to cover 1.04 crore households, provide 2.5 lakh community toilets, 2.6 lakh public toilets, and a solid waste management facility in each town. -

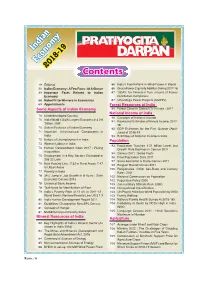

Some Aspects of Indian Economy Mineral Resources of India Forest

19 Editorial 86 India’s Fourth Rank in Wind Power in World 20 Indian Economy : A Few Facts : At A Glance 86 Green Power Capacity Addition During 2017-18 29 Important Facts Related to Indian 87 ‘UDAY’ for Financial Turn around of Power Economy Distribution Companies 68 Nobel Prize Winners in Economics 87 Ultra Mega Power Projects (UMPPs) 69 Appointments Forest Resources of India Some Aspects of Indian Economy 89 Forest Cover in States/UTs in India : 2017 National Income of India 70 Underdeveloped Country 90 Concepts of National Income 70 India World’s Sixth Largest Economy at $ 2·6 91 Provisional Estimates of Annual Income, 2017- Trillion : IMF 18 70 Salient Features of Indian Economy 92 GDP Estimates for the First Quarter (April- 71 Important Infrastructural Components in June) of 2018-19 India 93 Estimates of National Income in India 72 Nature of Unemployment in India Population 73 Woman Labour in India 93 Population Touches 1·21 billion Level, but 73 Human Development Index 2017 : Rising Growth Rate Declines in Census 2011 Inequalities 94 Census 2011 : Some Facts 75 Employment in 8 Key Sectors Estimated at 96 Final Population Data 2011 205·22 Lakh 97 Socio-Economic & Caste Census 2011 ` ` 75 New Poverty Line : 32 in Rural Areas, 47 99 Religion Based Census 2011 in Urban Areas 100 Religionwise Child Sex-Ratio and Literacy 77 Poverty in India Rate : 2011 78 34% Jump in Job Growth in 8 Years : Sixth 102 National Commission on Population Economic Census 2013 102 Population Policy 2000 78 Universal Basic Income 103 Janasankhya Sthirata Kosh