© Ray a V Ery / C T S IMA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

CATALOGUE WELCOME to NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS and NAXOS NOSTALGIA, Twin Compendiums Presenting the Best in Vintage Popular Music

NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS/NOSTALGIA CATALOGUE WELCOME TO NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS AND NAXOS NOSTALGIA, twin compendiums presenting the best in vintage popular music. Following in the footsteps of Naxos Historical, with its wealth of classical recordings from the golden age of the gramophone, these two upbeat labels put the stars of yesteryear back into the spotlight through glorious new restorations that capture their true essence as never before. NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS documents the most vibrant period in the history of jazz, from the swinging ’20s to the innovative ’40s. Boasting a formidable roster of artists who forever changed the face of jazz, Naxos Jazz Legends focuses on the true giants of jazz, from the fathers of the early styles, to the queens of jazz vocalists and the great innovators of the 1940s and 1950s. NAXOS NOSTALGIA presents a similarly stunning line-up of all-time greats from the golden age of popular entertainment. Featuring the biggest stars of stage and screen performing some of the best- loved hits from the first half of the 20th century, this is a real treasure trove for fans to explore. RESTORING THE STARS OF THE PAST TO THEIR FORMER GLORY, by transforming old 78 rpm recordings into bright-sounding CDs, is an intricate task performed for Naxos by leading specialist producer-engineers using state-of-the-art-equipment. With vast personal collections at their disposal, as well as access to private and institutional libraries, they ensure that only the best available resources are used. The records are first cleaned using special equipment, carefully centred on a heavy-duty turntable, checked for the correct playing speed (often not 78 rpm), then played with the appropriate size of precision stylus. -

Neglected Jazz Figures of the 1950S and Early 1960S New World NW 275

Introspection: Neglected Jazz Figures of the 1950s and early 1960s New World NW 275 In the contemporary world of platinum albums and music stations that have adopted limited programming (such as choosing from the Top Forty), even the most acclaimed jazz geniuses—the Armstrongs, Ellingtons, and Parkers—are neglected in terms of the amount of their music that gets heard. Acknowledgment by critics and historians works against neglect, of course, but is no guarantee that a musician will be heard either, just as a few records issued under someone’s name are not truly synonymous with attention. In this album we are concerned with musicians who have found it difficult—occasionally impossible—to record and publicly perform their own music. These six men, who by no means exhaust the legion of the neglected, are linked by the individuality and high quality of their conceptions, as well as by the tenaciousness of their struggle to maintain those conceptions in a world that at best has remained indifferent. Such perseverance in a hostile environment suggests the familiar melodramatic narrative of the suffering artist, and indeed these men have endured a disproportionate share of misfortunes and horrors. That four of the six are now dead indicates the severity of the struggle; the enduring strength of their music, however, is proof that none of these artists was ultimately defeated. Selecting the fifties and sixties as the focus for our investigation is hardly mandatory, for we might look back to earlier years and consider such players as Joe Smith (1902-1937), the supremely lyrical trumpeter who contributed so much to the music of Bessie Smith and Fletcher Henderson; or Dick Wilson (1911-1941), the promising tenor saxophonist featured with Andy Kirk’s Clouds of Joy; or Frankie Newton (1906-1954), whose unique muted-trumpet sound was overlooked during the swing era and whose leftist politics contributed to further neglect. -

November/December 2005 Issue 277 Free Now in Our 31St Year

jazz &blues report november/december 2005 issue 277 free now in our 31st year www.jazz-blues.com Sam Cooke American Music Masters Series Rock & Roll Hall of Fame & Museum 31st Annual Holiday Gift Guide November/December 2005 • Issue 277 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum’s 10th Annual American Music Masters Series “A Change Is Gonna Come: Published by Martin Wahl The Life and Music of Sam Cooke” Communications Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductees Aretha Franklin Editor & Founder Bill Wahl and Elvis Costello Headline Main Tribute Concert Layout & Design Bill Wahl The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and sic for a socially conscientious cause. He recognized both the growing popularity of Operations Jim Martin Museum and Case Western Reserve University will celebrate the legacy of the early folk-rock balladeers and the Pilar Martin Sam Cooke during the Tenth Annual changing political climate in America, us- Contributors American Music Masters Series this ing his own popularity and marketing Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, November. Sam Cooke, considered by savvy to raise the conscience of his lis- Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, many to be the definitive soul singer and teners with such classics as “Chain Gang” Peanuts, Mark Smith, Duane crossover artist, a model for African- and “A Change is Gonna Come.” In point Verh and Ron Weinstock. American entrepreneurship and one of of fact, the use of “A Change is Gonna Distribution Jason Devine the first performers to use music as a Come” was granted to the Southern Chris- tian Leadership Conference for ICON Distribution tool for social change, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the fundraising by Cooke and his manager, Check out our new, updated web inaugural class of 1986. -

Drums • Bobby Bradford - Trumpet • James Newton - Flute • David Murray - Tenor Sax • Roberto Miranda - Bass

1975 May 17 - Stanley Crouch Black Music Infinity Outdoors, afternoon, color snapshots. • Stanley Crouch - drums • Bobby Bradford - trumpet • James Newton - flute • David Murray - tenor sax • Roberto Miranda - bass June or July - John Carter Ensemble at Rudolph's Fine Arts Center (owner Rudolph Porter)Rudolph's Fine Art Center, 3320 West 50th Street (50th at Crenshaw) • John Carter — soprano sax & clarinet • Stanley Carter — bass • William Jeffrey — drums 1976 June 1 - John Fahey at The Lighthouse December 15 - WARNE MARSH PHOTO Shoot in his studio (a detached garage converted to a music studio) 1490 N. Mar Vista, Pasadena CA afternoon December 23 - Dexter Gordon at The Lighthouse 1976 June 21 – John Carter Ensemble at the Speakeasy, Santa Monica Blvd (just west of LaCienega) (first jazz photos with my new Fujica ST701 SLR camera) • John Carter — clarinet & soprano sax • Roberto Miranda — bass • Stanley Carter — bass • William Jeffrey — drums • Melba Joyce — vocals (Bobby Bradford's first wife) June 26 - Art Ensemble of Chicago Studio Z, on Slauson in South Central L.A. (in those days we called the area Watts) 2nd-floor artists studio. AEC + John Carter, clarinet sat in (I recorded this on cassette) Rassul Siddik, trumpet June 24 - AEC played 3 nights June 24-26 artist David Hammond's Studio Z shots of visitors (didn't play) Bobby Bradford, Tylon Barea (drummer, graphic artist), Rudolph Porter July 2 - Frank Lowe Quartet Century City Playhouse. • Frank Lowe — tenor sax • Butch Morris - drums; bass? • James Newton — cornet, violin; • Tylon Barea -- flute, sitting in (guest) July 7 - John Lee Hooker Calif State University Fullerton • w/Ron Thompson, guitar August 7 - James Newton Quartet w/guest John Carter Century City Playhouse September 5 - opening show at The Little Big Horn, 34 N. -

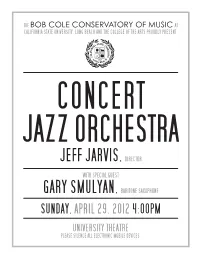

Jeff Jarvis,Director

CONCERT JAZZ ORCHESTRA JEFF JARVIS, DIRECTOR WITH SPECIAL GUEST GARY SMULYAN, BARITONE SAXOPHONE SUNDAY, APRIL 29, 2012 4:00PM UNIVERSITY THEATRE PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. TONIGHT’S PROGRAM GENTLY / Bob Mintzer This well-crafted original is the title track of a recording of the Bob Mintzer Big Band. This recording project was unique in that the horn section stood in a circle surrounding a specially designed ribbon microphone that was extremely sensitive and accurate. This microphone would not accept loud dynamic levels, so Bob Mintzer wrote material that showcased the band playing at softer dynamics, which resulted in frequent use of muted brass, flugelhorns, and woodwinds. Today’s soloists include Josh Andree (tenor sax) and Will Brahm (guitar). THEN AND NOW / George Stone This terrific original composition and arrangement is featured on a recent recording of the George Stone Big Band entitled “The Real Deal”, performed by a collection of Southern California’s finest studio musicians. George’s music is frequently featured at our concerts because of its superior quality, both from a compositional standpoint and also in terms of orchestration. This piece has it all—melodic integrity, intense rhythms, lush harmonies, and sufficient solo space. Today’s soloists include Eun young Koh (piano), Josh Andree (tenor sax), Will Brahm (guitar), and Daniel Hutton (alto sax). CHINA BLUE / Jeff Jarvis Originally composed as a commission for a big band in Williamsburg VA, the work features a winding trumpet melody supported by muted trombone parts, warm flugelhorn lines, and beautiful woodwind parts played by the saxophone section. The piece proves challenging since the musicians are faced with executing exposed parts with delicacy and restraint. -

ED 110 544 Individualized Language Arts

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 110 544 88 UD 015 350 TITLE Individualized Language Arts--Diagnosis, Prescription, Evaluation. A Teacher's 'Resource Manual...ESEA Title III Project: 70-014. INSTITUTION Weehawken Board of Education, N.J. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 308p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$15.86 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Curriculum Guides; *Diagnostic Teaching; Educational Diagnosis; Educational Resources; Elementary School Curriculum; Instructional Materials; *Language-Arts; Manuals; Secondary Education; *Teaching. Guides; Writing Exercises; *Writing Skills IDENTIFIERS *Elementary Secondary Education ActTite1 e III; ESEA Title III; New Jersey; Weehawken ABSTRACT l This document is a teachers' resource manual, grades Kindergarten through Twelve, for the promotion of students' facility in written composition in the context ofa language-experience approach and through the use of diagnostic-prescriptivetechniques derived from modern linguistic'theory. The "IndividualizedLanguage Arts: Diagnosis; Prescription, and Evaluation" project (on which this manual is based) was validated in 1973 by the standards and guidelines of the U.S. Office of Educationas innovative, successful, cost-effective, and exportable. As a result of the validation,the project is now funded as a demonstration site by the New Jersey ESEA Title III program. This Project, it is stated,was designed to meet the critical need of educators to developmore effective methods of analyzing students' writing, and to prescribe and apply individualized instructional techniques in order to promotegreater writing facility. The students' writing development is traced by three samples, taken at three intervals during theyear. The __evaluation of the samples, based on commonly acceptedLanguage Arts objectives is considered to pinpoint each student'scurrent strengths and needs. A prescriptive program which is said to emphasize the integration of subject areas is used inn this Project. -

1993 February 24, 25, 26 & 27, 1993

dF Universitycrldaho LIoNEL HmPToN/CHEVRoN JnzzFrsrr\Al 1993 February 24, 25, 26 & 27, 1993 t./¡ /ìl DR. LYNN J. SKtNNER, Jazz Festival Executive Director VtcKt KtNc, Program Coordinator BRTNoR CAtN, Program Coordinator J ¡i SusnN EHRSTINE, Assistant Coordinator ltl ñ 2 o o = Concert Producer: I É Lionel Hampton, J F assisted by Bill Titone and Dr. Lynn J. Skinner tr t_9!Ð3 ü This project is supported in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts We Dedicate this 1993 Lionel Hømpton/Chevron Jøzz Festivül to Lionel's 65 Years of Devotion to the World of Juzz Page 2 6 9 ll t3 r3 t4 l3 37 Collcgc/Univcrsity Compctition Schcdulc - Thursday, Feh. 25, 1993 43 Vocal Enserrrbles & Vocal Conrbos................ Harnpton Music Bldg. Recital Hall ...................... 44 45 46 47 Vocal Compctition Schcrlulc - Fridav, Fcli. 2ó, 1993 AA"AA/AA/Middle School Ensenrbles ..... Adrrrin. Auditoriunr 5l Idaho Is OurTenitory. 52 Horizon Air has more flights to more Northwest cities A/Jr. High/.Ir. Secondary Ensenrbles ........ Hampton Music Blclg. Recital Hall ...............,...... 53 than any other airline. 54 From our Boise hub, we serve the Idaho cities of Sun 55 56 Valley, Idaho Falls, Lewiston, MoscowÆullman, Pocatello and AA/A/B/JHS/MIDS/JR.SEC. Soloists ....... North Carnpus Cenrer ll ................. 57 Twin Falls. And there's frequent direct service to Portland, lnstrurncntal Corupctilion'Schcrlulc - Saturday, Fcll. 27, 1993 Salt Lake City, Spokane and Seattle as well. We also offer 6l low-cost Sun Valley winter 8,{. {ÀtûåRY 62 and summer vacation vt('8a*" å.t. 63 packages, including fOFT 64 airfare and lodging. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Joe Henderson: a Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 12-5-2016 Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations © 2016 JOEL GEOFFREY HARRIS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School JOE HENDERSON: A BIOGRAPHICAL STUDY OF HIS LIFE AND CAREER A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Joel Geoffrey Harris College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music Jazz Studies December 2016 This Dissertation by: Joel Geoffrey Harris Entitled: Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in the College of Performing and Visual Arts in the School of Music, Program of Jazz Studies Accepted by the Doctoral Committee __________________________________________________ H. David Caffey, M.M., Research Advisor __________________________________________________ Jim White, M.M., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Socrates Garcia, D.A., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Stephen Luttmann, M.L.S., M.A., Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense ________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School _______________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. Associate Provost and Dean Graduate School and International Admissions ABSTRACT Harris, Joel. Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career. Published Doctor of Arts dissertation, University of Northern Colorado, December 2016. This study provides an overview of the life and career of Joe Henderson, who was a unique presence within the jazz musical landscape. It provides detailed biographical information, as well as discographical information and the appropriate context for Henderson’s two-hundred sixty-seven recordings. -

1959 Jazz: a Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959

GELB, GREGG, DMA. 1959 Jazz: A Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959. (2008) Directed by Dr. John Salmon. 69 pp. Towards the end of the 1950s, about halfway through its nearly 100-year history, jazz evolution and innovation increased at a faster pace than ever before. By 1959, it was evident that two major innovative styles and many sub-styles of the major previous styles had recently emerged. Additionally, all earlier practices were in use, making a total of at least ten actively played styles in 1959. It would no longer be possible to denote a jazz era by saying one style dominated, such as it had during the 1930s’ Swing Era. This convergence of styles is fascinating, but, considering that many of the recordings of that year represent some of the best work of many of the most famous jazz artists of all time, it makes 1959 even more significant. There has been a marked decrease in the jazz industry and in stylistic evolution since 1959, which emphasizes 1959’s importance in jazz history. Many jazz listeners, including myself up until recently, have always thought the modal style, from the famous 1959 Miles Davis recording, Kind of Blue, dominated the late 1950s. However, a few of the other great and stylistically diverse recordings from 1959 were John Coltrane’s Giant Steps, Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz To Come, and Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, which included the very well- known jazz standard Take Five. My research has found many more 1959 recordings of equally unique artistic achievement. -

The Guardian, April 8, 1966

Wright State University CORE Scholar The Guardian Student Newspaper Student Activities 4-8-1966 The Guardian, April 8, 1966 Wright State University Student Body Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/guardian Part of the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Wright State University Student Body (1966). The Guardian, April 8, 1966. : Wright State University. This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Activities at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Guardian Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Guardian A Wright State Campus Publication Volume 2 FRIDAY, APRIL 8. 1966 Number 10 Plans Set For Proposed Park llv ST» VI T\< KI TT Paths running through the wools were also proposed. By the beginning of the Kali It was suggested that the paths trimester, Wright State's park be covered with limstone to could become a reality. keep them from becoming too Terry Hankey, recently ap- muddy in rainy weather. The pointed Park Commissioner paths that exist now, run in by Bob Beachdell, Student only one direction. The com- Body President, called a mittee decided that it would meeting on Wednesday, March serve the area better If nature 30, to discuss plans for the trails were Initiated to make proposed park in the rear of it easier for students to enjoy Allyn Hall. The meeting was all of the woods. attended by several members Hankey closed the meeting of Hankey's planning com- by saying, "Our progress on mittee, which consisted of stu- this proposal is wholly de- dents Interested in seeing the pend ;nt on student support.