Geoff Miller Senior Thesis Chapter Below Written for History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Una Città Come Eredità

SPORT Per Agnelli Il mestiere Ha in mano la Fiorentina del dopo Baggio il no di Nannini di presidente non offusca e forse ha già avuto il tempo per pentirsi il fascino Ferrari Cecchi Gori «Ho trovato una società vecchia: ci vorrà Il nfiuto di Alessandro Nannini di guidare per un anno la Fcr un anno per tornare a puntare in alto» ran di FI è dispiaciuto al presidente della Fiat Gnnni Agnelli (nella foto) che lo considera «un buon pilota- Tuttavia ha continuato Agnelli il no del pilota della Benetton non ap panna il fascino della casa di Maranello che resta immutato nel tempo e «un gran premio di Formula uno senza la Ferran sarebbe come un campionato di calcio senza la Juventus» Segna e viene Decine di arrestati e nume rosi (enti ien a Edimburgo aggredito provocati da una catena di Una città incidenti scoppiati durante Arresti e feriti I incontro Hibemian Hcart, in Scozia derby cittadino Ipnmi scon tri si sono verificati al 13 del pnmo tempo, quando gli Hearts sono passati in vantaggio con un gol di Robertson aggredito da un tifoso dell Hibemian Ne è seguita un inva come eredità sione di campo e la partita è stata sospesa L'editore Maxwell ti magnate bntannico dell c- ditona, Robert Maxwell che compra anche ha già quote sociali nelle Mano Cecchi Gori, classe 1920, produttore cinema il possibile e I impossibile per proposito di Previdi a Firenze ilTottenham squadre di Derby. Manche tografico di fama intemazionale (oltre trent'anni di una grande Fiorentina, tra un circola con insistenza la voce ster United, Oxford e Rea- successi da «Il Sorpasso» a «Rosencrantz e Guilden- anno vedrete» che il suo posto verrà preso da Costo 26 miliardi ding, ha avuto via libera dai stem sono morti», vincitore ien del Leone d'Oro a Intanto, qualcosa si muove Luciano Moggi il cui contratto ,^^^_^_^^^^__ dirigenu del Tottenham Hot- col Napoli scade a dicembre. -

REVISTA AL PRESIDENTE Argentina´S Rivals E-Mail: [email protected] CLAUDIO TAPIA PREDIO JULIO HUMBERTO GRONDONA Interview – President Claudio Tapia Autopista Tte

3 COMITÉ EJECUTIVO ASOCIACIÓN DEL FÚTBOL ARGENTINO AFA Executive Committee PRESIDENTE President TESORERO Treasurer Sr. / Mr. Claudio Fabián Tapia Sr. / Mr. Alejandro Miguel Nadur (Presidente / President at Club Barracas Central) (Presidente / President at Club A. Huracán) VICEPRESIDENTE 1° vicepresident 1° PROTESORERO Protreasurer Dr. Daniel Angelici Sr. / Mr. Daniel Osvaldo Degano (Presidente / President at Club A. Boca Juniors) (Vicepresidente / Vicepresident at Club A. Los Andes) VICEPRESIDENTE 2° vicepresident 2° VOCALES Vocals Sr. / Mr. Hugo Antonio Moyano Dr. Raúl Mario Broglia (Presidente / President at Club A. Independiente) (Presidente / President at Club A. Rosario Central) Dr. Pascual Caiella VICEPRESIDENTE 3° vicepresident 3° (Presidente / President at Club Estudiantes de La Plata) Sr. / Mr. Guillermo Eduardo Raed Sr. / Mr. Nicolás Russo (Presidente / President at Club A. Mitre - Santiago del Estero) (Presidente / President at Club A. Lanús) Sr. / Mr. Francisco Javier Marín SECRETARIO EJECUTIVO DE LA PRESIDENCIA (Vicepresidente / Vicepresident at Club A. Acassuso) Executive Secretary to Presidency Sr. / Mr. Adrián Javier Zaffaroni Sr. / Mr. Pablo Ariel Toviggino (Presidente / President at Club S. D. Justo José Urquiza) Dra. María Sylvia Jiménez SECRETARIO GENERAL (Presidente / President at Club San Lorenzo de Alem - Catamarca) Sr. / Mr. Víctor Blanco Rodríguez Sr. / Mr. Alberto Guillermo Beacon (Presidente / President at Racing Club) (Presidente / President at Liga Rionegrina de Fútbol) PROSECRETARIO Sr. / Mr. Marcelo Rodolfo Achile (Presidente / President at Club Defensores de Belgrano) MIEMBROS SUPLENTES Alternate Members SUPLENTE 1 Alternate 1 SUPLENTE 4 Alternate 4 SUPLENTE 7 Alternate 7 Dr. José Eduardo Manzur A designar Sr. / Mr. Dante Walter Majori (Presidente / President at Club D. Godoy To be designed (Presidente / President at Club S. -

La Hora Más Gloriosa Del Fútbol Argentino

EDICIÓN ESPECIAL LALA HORAHORA MÁSMÁS GLORIOSAGLORIOSA DELDEL FÚTBOLFÚTBOL ARGENTINOARGENTINO 86 Felices por lo que hicimos y por lo que haremos Cuando los hechos superan a las palabras, las palabras están de más. O, mejor dicho, NO ALCANZAN PARA PODER DECIRLO TODO. El Gráfico está tan feliz como todos los argentinos. Esta noche de histórico domingo, sentimos que su alma sonríe y en cada uno de los teclados, los periodistas que hacen El Gráfico deslizan su emoción. Es fácil en- tender que se trata de un día especial. En esta hora -en que queremos decirlo todo- NOS DAMOS CUENTA DE QUE SOLO HAY UNA MANE- RA DE EXPRESARNOS: brindar esta edición en la que volcamos con conceptos, fotos y testimonios EL DIA MAS GLORIOSO DEL FUTBOL ARGENTINO. Para nosotros no es el final de nada; acaso -¿por qué no confesarlo?- podría ser el comienzo de todo. Estamos felices por el triunfo de la Selección y, ya más calmados del primer impacto, estamos felices por todo cuanto hicimos desde el primer día del proceso, al que también podríamos llamar “La Era Menotti” o el “Operativo Mundial 78”. Si no dijéramos que hemos recibido muchas felicitaciones por nuestro trabajo antes y durante el Mundial seríamos insensibles. Nos gustó que nos reconocieran el esfuerzo (ojo, esfuerzo no es sacrificio), pero no encontrábamos la forma adecuada para el agradecimiento. Decir gra- cias es tan convencional como decir “es nuestra obligación”. Detrás de la obligación pusimos el alma del periodista. Y el alma del periodista es su amor, su pasión y su deseo. El Mundial nos obligó a todos los ar- gentinos a esforzarnos; El Gráfico cumplió su papel: durante este mes de junio realizamos las cuatro ediciones normales, más otras tres ediciones extras. -

Yo Soy El Diego De La Gente

Diego Armando Maradona (Buenos Aires, 1961), jugador zurdo, poseedor de una extraordinaria técnica y una singular destreza con el balón, destacó pronto en una época marcada por la paulatina desaparición de las grandes figuras del fútbol. Internacional desde los 16 años, en su meteórica carrera pasó el F.C. Barcelona (con quien conquistó la Copa del Rey y la Copa de la Liga), en una estancia polémica, donde se ganó decididos partidarios y apasionados detractores. Pasó hacia tiempo, por sobrados méritos, a la galeria de hombres ilustres, de genios del deporte, que arrasan masas y corazones. Su historia, con tintes de melodrama, está en boca de to- dos. Pero, hay cosas que están sólo acá adentro, en mi corazón y que nadie sabe, dice Maradona en este libro. ¿Quién puede saber qué pasaba por su cabeza antes de dormir, en una piecita de dos por dos, en Fiorito, acom- pañado por sus siete hermanos? ¿Quién osaría afirmar cuál fue su mayor alegría y su peor tristeza? Nadie mejor que el propio Diego, perdón, El Diego... de la gente, como a él le gusta ser y que lo llamen. Desde sus hu- mildísimos orígenes, hasta la mayor de las glorias, pas- ando por cada una de sus muertes y sus respactivas re- surrecciones, por las definiciones de sus amigos y sus enemigos, todo queda relatado aquí, en este libro, en primera persona, donde se descubre un Maradona ín- tegro y también íntimo. Un Maradona que se confiesa sin reservas. Diego Armando Maradona Yo soy el Diego ePUB v1.0 GONZALEZ 19.10.11 Realización: Daniel Arcuchi y Ernesto Cherquis Bialo EDITORIAL PLANETA ISBN 950-49-0228-6 Nº Edición: 1ª Año de edición: 2006 A Dalma Nerea y Gíaninna Dinorah Maradona. -

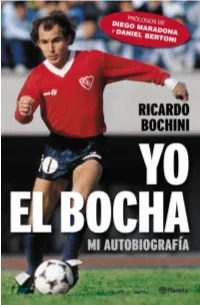

35348 Yoelbocha Primercap.Pdf

RICARDO BOCHINI Ese domingo jugábamos contra Racing en el Cilindro. YO, EL BOCHA Habíamos llegado dos días antes de Italia, donde le habíamos MI AUTOBIOGRAFÍA ganado a Juventus y yo había hecho el gol del triunfo. Me acuerdo de que todo el mundo aplaudió. Fue impresionante. La gente de Racing estuvo muy bien, nos hizo un homenaje en el centro del campo. Nosotros entramos con las tres copas que habíamos ganado ese año: la Libertadores, la Interamericana Prólogos y la Intercontinental. Sería imposible repetir ese recibimiento Diego Maradona hoy, hay demasiada rivalidad. Pero antes se podía hacer. Esto Daniel Bertoni pasó a fines de noviembre de 1973. Ese día ganamos 3 a 1. Después del partido volví a mi casa en Zárate. Hacía bastante Realización tiempo que no iba. Había una multitud esperándome para ho- Jorge Barraza menajearme. Fue una de las alegrías más grandes de mi vida. Me recibió el intendente Miguel Scola, padre de Juan Scola, que jugaba en San Lorenzo y estuvo conmigo en el selecciona- do juvenil que fue a Cannes. Después fuimos a mi barrio, Villa Angus, y estaba el vecindario entero reunido alrededor de mi casa. Y mucha gente de todos los barrios de Zárate, había miles. Era una locura. La emoción fue muy grande. Había tanta gente que se empezaron a subir a los techos. Y el techo de mi casa era de chapa, casi se viene abajo. Mi tía Ventura, que vivía con nosotros, lloraba en serio, angustiada: 17 BOCHINI-Yo, el Bocha.indd 5 4/12/16 12:24 PM BOCHINI-Yo, el Bocha.indd 17 4/12/16 12:24 PM RICARDO BOCHINI Ese domingo jugábamos contra Racing en el Cilindro. -

Version Preliminar Susceptible De Correccion

“2017‐ Año de las Energías Renovables” Senado de la Nación Secretaría Parlamentaria Dirección General de Publicaciones VERSION PRELIMINAR SUSCEPTIBLE DE CORRECCION UNA VEZ CONFRONTADO CON EL ORIGINAL IMPRESO “2017 ‐ Año de las Energías Renovables” (S-4720/17) PROYECTO DE DECLARACION El Senado de la Nación DECLARA Su beneplácito por la destacada participación del Club Atlético Independiente en la Copa CONMEBOL Sudamericana 2017, al consagrarse Campeón en el mítico Estadio Maracaná de Río de Janeiro frente al Clube Regatas do Flamengo, volviendo a celebrar un título internacional, lo que rememora los años más gloriosos y brillantes de la era dorada del fútbol argentino a nivel continental e internacional en lo que a clubes se refiere. Lucila Crexell.- FUNDAMENTOS Señora Presidente: El pasado miércoles 13 de Diciembre del corriente año, el Club Atlético Independiente conquistó su segunda Copa CONMEBOL Sudamericana, luego de empatar 1 a 1 con el Flamengo de Brasil, en un partido que se desarrolló en el mítico Estadio Maracaná, acrecentado así la leyenda del “Rey de Copas”. En el primer partido decisivo Independiente había vencido al conjunto brasileño por 2 a 1, con los goles de Emmanuel Gigliotti y Maximiliano Meza, y necesitaba un empate para consagrarse Campeón de esta nueva edición de la Copa Sudamericana. Si bien, durante la primera parte del encuentro el equipo “carioca” puso en aprietos al de Avellanada con el gol marcado por Lucas Paquetá ante un Maracaná eufórico, apenas unos minutos más tarde, el joven Ezequiel Barco logró el empate al tomar la pelota y ejecutar el tiro libre penal, acallando las voces del Maracaná, gol que a la postre le terminaría dando el tan ansiado título al “Rey de Copas”. -

MUNDIAL 78 Suplemento Página/12, 01/06/08 El Gauchito Gil

MUNDIAL 78 Suplemento Página/12, 01/06/08 El gauchito gil Hace exactamente 30 años, el 1º de junio de 1978, empezaba en Buenos Aires el Mundial de fútbol. Durante el mes siguiente desaparecerían 63 personas, Videla recibiría seis veces diferentes el aplauso de un estadio lleno de argentinos y la prensa local se cuadraría casi con unanimidad para refutar “la campaña antiargentina” que en el mundo denunciaba los crímenes de la dictadura. El hecho de que este mes se organice en el Monumental “la otra final”, un acto que reivindicará la vigencia de los derechos humanos, y las reacciones revulsivas que despierta, invitan a revisitar los sentimientos y argumentos complejos y contradictorios que sigue despertando aquella Copa. Por Gustavo Veiga Trilogía: “Conjunto de tres obras trágicas que un autor presentaba a concurso en los juegos de la antigua Grecia”. Comprender el significado que tiene el Mundial ’78 para la Argentina de los últimos treinta años requiere de un paso previo: la búsqueda de similitudes en procesos semejantes. La rueda de la historia gira (Benito Mussolini en el Mundial de Italia del ’34), gira (Adolf Hitler en los Juegos Olímpicos de Berlín del ’36) y sigue girando (Jorge Rafael Videla en un estadio de River colmado). En ese trípode se apoya un paradigma del acontecimiento deportivo que explica cómo tres dictaduras del siglo XX se apropiaron de su subjetividad, de los valores que representa el deporte para la política cuando ésta lo necesita. Las tres pudieron glorificar de manera extrema los éxitos de sus atletas, porque la Italia del Duce se consagró campeón, la Alemania del Führer ganó con holgura los juegos que organizó y la Argentina obtuvo su primer título mundial de fútbol. -

Fútbol Argentino: Crónicas Y Estadísticas

Fútbol Argentino: Crónicas y Estadísticas Asociiaciión dell Fútboll Argentiino - 1ª Diiviisiión – 1973 Luis Alberto Colussi Carlos Alberto Guris Victor Hugo Kurhy Fútbol Argentino: Crónicas y Estadísticas – A.F.A. – 1ª División - 1973 2 1973: Un año para recordar. Metropolitano. El primer campeonato de 1973 fue disputado por 17 clubes, uno menos que en el año precedente, por cuanto descendieron Lanús y Banfield y ascendió All Boys, institución que no jugaba en Primera División desde 1926. En la previa, el gran candidato al título era San Lorenzo, que se había quedado con las dos competencias de 1972. Los principales candidatos a destronarlo eran River Plate, que incorporó a Enrique Wolff y Edgardo Di Meola; Boca Juniors, que se reforzó con Jorge Benítez de Racing, Vicente Pernía de Estudiantes de La Plata y el cordobés Carlos Guerini. Tampoco había que descartar a Independiente, aunque su participación en la Copa Libertadores le restaba chances. Pocos pensaban que el gran animador del campeonato iba a ser Huracán. Con la dirección técnica de César Menotti, el Globito formó un equipo que es recordado como uno de los mejores en la historia del fútbol argentino. Jugó virtualmente con 5 delanteros, aunque dos de ellos partían desde el medio campo, conformando una línea de forwards a la vieja usanza, integrada por Houseman, Brindisi, Avallay, Babington y Larrosa. El equipo se complementaba con una defensa de experiencia y personalidad, en la que sobresalían Basile y Carrascosa. El arranque de Huracán fue extraordinario e indicativo de lo que sería su actuación en el campeonato. Ganó sus 6 primeros partidos, con 22 goles anotados y 4 en contra, incluyendo goleadas frente a Argentinos Juniors, Atlanta y Racing. -

Fifa World Cup™: Statistics

Final matches overview - Les finales en un clin d’oeil Resumen de partidos finales - Endspiele im Überblick 1930/Uruguay Final: Uruguay – Argentina 4-2 (1-2) Montevideo / Centenario – 30 July 1930 Attendance: 80,000 Referee: LANGENUS Jan (BEL) Scorers: Pablo DORADO (URU) 12, Carlos PEUCELLE (ARG) 20, Guillermo STABILE (ARG) 37, Pedro CEA (URU) 57, Victoriano Santos IRIARTE (URU) 68, Hector CASTRO (URU) 89 3rd place: USA Top Goalscorer: Guillermo STABILE (ARG) 8 goals 1934/Italy Final: Italy – Czechoslovakia 2-1 AET (1-1, 0-0) Rome / Nazionale PNF – 10 June 1934 Attendance: 50,000 Referee: EKLIND Ivan (SWE) Scorers: Antonin PUC (TCH) 76+, Angelo SCHIAVIO (ITA) 95+, Raimondo ORSI (ITA) 81 3rd place match: GER – AUT 3-2 (3-1) Golden Shoe: NEJEDLY (TCH) 5 goals 1938/France Final: Italy – Hungary 4-2 (3-1) Paris/Colombes / Olympique – 19 June 1938 Attendance: Referee: CAPDEVILLE George (FRA) Scorers: Gino COLAUSSI (ITA) 6, Pal TITKOS (HUN) 8, Silvio PIOLA (ITA) 16, Gino COLAUSSI (ITA) 35, Gyorgy SAROSI (HUN) 70, Silvio PIOLA (ITA) 82 3rd place match. BRA – SWE 4-2 (1-2) Top Goalscorer: LEONIDAS (BRA) 7 goals 1950/Brazil Final round Uruguay, Brazil, Sweden, Spain Rio De Janeiro / Estádio do Maracanã & Sao Paulo / Pacaembu – 09-16 July 1950 Referees final round: URU-BRA: George READER (ENG), SWE-ESP: Karel VAN DER MEER (NED), URU-SWE: Giovanni GALEATI (ITA), BRA-ESP: Reginald LEAFE (ENG), URU-ESP: Benjamin GRIFFITHS (WAL), BRA-SWE: Arthur ELLIS (ENG) 1st 2nd & 3rd place: Uruguay, Brazil, Sweden Top Goalscorer: ADEMIR (BRA) 9 goals FIFA WORLD -

Wm-Vorschau Des Spielverlagerung.De Teams

WM-VORSCHAU DES SPIELVERLAGERUNG.DE TEAMS www.spielverlagerung.de SPIELVERLAGERUNG WM-VORSCHAU 1 INHALT DEUTSCHLAND 28 SCHWEIZ 256 PORTUGAL 41 ECUADOR 268 GHANA 54 FRANKREICH 275 HONDURAS 287 USA 64 KOLUMBIEN 183 GRIECHENLAND 192 ELFENBEINKÜSTE 199 BRASILIEN 75 JAPAN 205 ARGENTINIEN 292 KROATIEN 98 BOSNIEN 313 MEXIKO 113 IRAN 320 KAMERUN 120 URUGUAY 216 NIGERIA 325 COSTA RICA 225 ENGLAND 230 ITALIEN 246 SPANIEN 125 BELGIEN 332 NIEDERLANDE 144 ALGERIEN 343 CHILE 155 RUSSLAND 347 AUSTRALIEN 178 SÜDKOREA 355 SPIELVERLAGERUNG WM-VORSCHAU 2 RENE MARIC / CONSTANTIN ECKNER / MARTIN RAFELT SO SEHEN SIEGER AUS 32 Länder treten bei der kommenden Weltmeisterschaft an, alle wollen sie gewinnen und bei einem halben Dutzend dürfte es wohl einem Weltuntergang gleichkommen, wenn sie nicht erfolgreich sein sollten. Weltmeister kann allerdings nur einer werden – also sind fünf Weltuntergänge vorprogrammiert. Doch was genau be- nötigt man, um das eine glückliche Land in dieser Glücks- und Wahrscheinlichkeitslotterie zu werden? Wir haben uns durch die Archive und Videomaterialien der bisherigen Weltmeisterschaften gewühlt, damit wir eine Antwort finden. Herausgekommen sind gleich mehrere. SPIELVERLAGERUNG WM-VORSCHAU 3 Trainercharisma! der Erfolg die Thesen des Trainers. Anders war es Anpassung an die Umstände! beim progressiven Niederländer Gertjan Verbeek, Richtet ein Trainer seine Mannschaft strategisch der schlussendlich mit dem 1. FC Nürnberg eine Von allen Seiten werden die klimatischen Be- wie taktisch aus, geht es nicht immer nur darum, Bruchlandung hinlegte. Er probierte viel, stellte dingungen bei der Weltmeisterschaft in Brasili- die besten Mittel zu wählen. Gleichsam wichtig teilweise recht unorthodox auf. Seine Spieler be- en als besondere Herausforderungen bezeichnet. ist, dass das Team, die Spieler, die das Vorgegebe- folgten den Plan, brachen aber nach Rückstän- Das lässt sich nicht so einfach pauschalisieren, ne auf dem Platz umsetzen müssen, wirklich an den meist brutal ein. -

Historia Koszulek Acf Fiorentiny W Latach 1926

HISTORIA KOSZULEK ACF FIORENTINY W LATACH 1926 - 2002 1926/27 Pierwsza koszulka w historii Fiorentiny, z którą oficjalnie zadebiutowała 3 października 1926 roku w Prima Divisione w meczu przeciwko Pizie. Jak możemy przeczytać w książce „Fiorentina 1926-27, le origini”: Zdecydowawszy się na wybór idealnego połączenia kolorów wywodzących się z jednej z dwóch pierwotnych drużyn, trzeba było ustalić nowy komplet stroju, w którym będą grali piłkarze Fiorentiny. […] Za wyborem nowych koszulek stał sam Ridolfi, zdecydował się na prosty, elegancki i efektowny wygląd. Połączenie biel-czerwień, które dzieliło koszulkę w pionie zarówno z przodu jak i z tyłu, prawa połowa była czerwona zaś lewa połowa biała. […] Nowe stroje, piękne i eleganckie, były wyjątkowe za sprawą precyzyjnie, ręcznie wyszywanej czerwonej lilijce na białym tle, która znajdowała się na wysokości serca. Miało to symbolizować nierozerwalną lojalność i miłość do Florencji oraz sprawiać, że gracze, którzy ją nosili odczuwali dumę. 1928/29 Pod koniec swojego pierwszego oficjalnego sezonu piłkarze Fiorentiny wybiegli na boisko na mecz towarzyski z Pro Vercelli w nowych strojach w białe i czerwone pionowe pasy. Od tego momentu stroje w sezonie 1927/28 były używane równolegle z tymi poprzednimi, zaś w następnym zupełnie je zastąpiły stając się jedynym oficjalnym wzorem. Zmianę ówczesnego wyglądu koszulek prawdopodonie spowodowały zarówno nowe „trendy” we włoskim futbolu, gdzie wiele drużyn grało w pasiastych strojach, jak i problemy, które wynikły podczas prania pierwszych oficjalnych strojów Fiorentiny. Jak się później okazało, i ta wersja strojów nie przetrwała długo, zaledwie jeden sezon. Częściowo z powodu rozczarowującego sezonu, a częściowo dlatego, że markiz Luigi Ridolfi zdecydowanie i gorliwie forsował pomysł aby koszulki miały kolor bliski jego sercu, kolor który od tego momentu, jak się przekonamy, stał się nierozerwalny z historią Fiorentiny: FIOLETOWY. -

GIRLPOWER JOSEPH S. BLATTER: TORLINIEN- TECHNOLOGIE MUSS HER MARIO KEMPES: “ARGENTINIEN IST DER FAVORIT” Belgi

1. NOVEMBER 2013 DEUTSCHE AUSGABE Fédération Internationale de Football Association – Seit 1904 JOSEPH S. BLATTER: TORLINIEN- TECHNOLOGIE MUSS HER PALÄSTINA: GIRLPOWER MARIO KEMPES: “ARGENTINIEN IST DER FAVORIT” Belgien hofft an der WM 2014 auf den grossen Coup FOR SHOOTING THE STARS WWW.FIFA.COM WWW.FIFA.COM/THEWEEKLY INHALT Belgien-Reportage Nord- und Mittel- Südamerika Das belgische Nationalteam im Hoch: Nach der souveränen amerika 10 Mitglieder Qualifikation für die WM 2014 liegt das Team von Coach 35 Mitglieder 5,5 WM-Plätze Marc Wilmots auf Rang 5 der FIFA-Weltrangliste. Wie es dazu 3,5 WM-Plätze www.conmebol.com kam und welche Chancen Belgien an der WM hat, lesen Sie in der www.concacaf.com grossen Reportage von Perikles Monioudis. Turning Point 7 Inside Alexi Lalas Der frühere Inter-Besitzer Massimo Moratti wird bejubelt, während 13 der “Clásico” zugunsten Barças ausgeht und Manchester United seine Hegemonialmacht verliert. Hertha BSC lernt dem FC Bayern das Fürchten. Die aktuellen Berichte aus vier Top-Ligen. Interview mit dem “Matador” Mario Kempes, der argentinischer Weltmeister von 1978, spricht 16 über seine neue Heimat die USA, den Star Lionel Messi und die optimale WM-Vorbereitung: “Kurz vor dem Turnier muss ein Spieler die Müdigkeit aus dem Fenster werfen.” Countdown Brasilien 2014 Thiago Silva steht als Captain der Seleção auf dem Höhepunkt 19 seiner Karriere. “Ich träume jeden Tag vom WM-Pokal”, sagt der Brasilianer 32 Wochen vor dem Turnier. Top 11 WM 2014 Vom Weissen Ballett bis zu Italiens Weltmeister-Team 1982: Countdown 23 Das sind unsere besten Fussballteams der Geschichte. Friedensbotschafterin Mit Leidenschaft und ohne Klischees: Die Geschichte der 29-jährigen Honey Thaljieh aus Palästina zeigt, wie der 25 Fussball Brücken schlagen kann.