The Development and Design of Bronze Ordnance, Sixteenth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tm 9-3305 Technical Manual Principles of Artillery Weapons Headquarters

Downloaded from http://www.everyspec.com TM 9-3305 TECHNICAL MANUAL PRINCIPLES OF ARTILLERY WEAPONS HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY 4 MAY 1981 Downloaded from http://www.everyspec.com *TM 9-3305 Technical Manual HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY No. 9-3305 Washington, DC, 4 May 1981 PRINCIPLES OF ARTILLERY WEAPONS REPORTING ERRORS AND RECOMMENDING IMPROVEMENTS You can help improve this manual. If you find any mistakes or if you know of a way to improve the procedures, please let us know. Mail your letter, DA Form 2028 (Recommended Changes to Publications and Blank Forms), or DA Form 2028-2, located in the back of this manual, direct to: Commander, US Army Armament Materiel Readiness Command, ATTN: DRSAR-MAS, Rock Island, IL 61299. A reply will be furnished to you. Para Page PART ONE. GENERAL CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1-1 1-1 2. HISTORY OF DEVELOPMENT Section I. General ....................................................................................................................... 2-1 2-1 II. Development of United States Cannon Artillery......................................................... 2-8 2-5 III. Development of Rockets and Guided Missiles ......................................................... 2-11 2-21 CHAPTER 3. CLASSIFICATION OF CURRENT FIELD ARTILLERY WEAPONS Section I. General ....................................................................................................................... 3-1 3-1 -

Singapore Defense Artillery Force

49 PUEiFACE * This document is one of a series prepared under instructions from the Supreme Cormmander for the Allied Powers to the Japanese Governrien-t (SCAPIN No. 126, 12 Oct 19'45). The series covers not only the operations of the Japanese armed forces during World War- II but also their operations in China and M4anchuria which preceded the world conflict. The original studies were written by former officers of the Japanese Army and Navy under the supervision of the Historical Rrecords Section of the First (Army) and Second (Navy) Demobilization Bureaus of the Japanese Govern aent. The manuscripts were translated by the ilitary Intelligence Service Group, G2, Headcuarters, Far East Commiiand. 1 tensive editing has ,been ac- colmplished by the Foreign Iistories Division of the Office of the Military History Officer, Headquarters, United States Aynj Japan. Monograph No. 68 is a report made 'by Lt Col. Tadataka Nu na- guchi of Army Technical: Ieadquarters and aij. Katsuji Akiyana of the Army Heavy Artillery.. School of an' inspection tour of Singapore and Java between Mj4arch and May 1;42. It covers the condition of the fortresses and weapons on those islands; an estimate of the nixiiber of weapons, since at that time a complete count had not been accomplished, and recowmendations in regard to their use and dis- posal. As the oasic manuscript fromil which this st~idy was prepared was particularly poor and filled. with. obvious errors, Lti. Col. NJumagu- chi, now a civilian in Tokyo, and Maj . Akiyama, now a colonel with the Japanese Self lDefense Force, have been interviewed on. -

Artillery Through the Ages, by Albert Manucy 1

Artillery Through the Ages, by Albert Manucy 1 Artillery Through the Ages, by Albert Manucy The Project Gutenberg EBook of Artillery Through the Ages, by Albert Manucy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Artillery Through the Ages A Short Illustrated History of Cannon, Emphasizing Types Used in America Author: Albert Manucy Release Date: January 30, 2007 [EBook #20483] Language: English Artillery Through the Ages, by Albert Manucy 2 Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ARTILLERY THROUGH THE AGES *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Christine P. Travers and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net ARTILLERY THROUGH THE AGES A Short Illustrated History of Cannon, Emphasizing Types Used in America UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Conrad L. Wirth, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. -- Price 35 cents (Cover) FRENCH 12-POUNDER FIELD GUN (1700-1750) ARTILLERY THROUGH THE AGES A Short Illustrated History of Cannon, Emphasizing Types Used in America Artillery Through the Ages, by Albert Manucy 3 by ALBERT MANUCY Historian Southeastern National Monuments Drawings by Author Technical Review by Harold L. Peterson National Park Service Interpretive Series History No. 3 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1949 (Reprint 1956) Many of the types of cannon described in this booklet may be seen in areas of the National Park System throughout the country. -

175 MM M113 Cannon: Historical Perspective on the P Cannon That

DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A: Unlimited Distribution 175 MM M113 Cannon: Historical Perspective on the Cannon that changed our Cannon Design Process David C. Smith, P.E NDIA Joint Armaments Symposium 14-17 May 2012 Background – Requirements Development of 175 MM M107 Howitzer ISO 9001 Certified FS15149 • Basic Requirements – Increased Mobility & Range in Heavy Artillery • Development Contract with PACCAR (Pacific Car and Foundry), Renton, WA and a Production Contract with BMY (Bowen & McLaughlin York) , York, PA, • M107 (175 MM Cannon)/M110 (8” Cannon) Self Propelled Howitzer began fielding in 1959 • Long term Plan - convert all 8” cannon-equipped vehicles to 175 MM Cannons and re- designate them M107 Howitzers by the mid-1960s. 2 Background – Requirements Development of 175 MM M107 Howitzer ISO 9001 Certified FS15149 • 175 MM Cannon Fielding – Roots of the 8”/175 MM Howitzer • 8” A rtill ery S yst em ( guns, ammuniti on) evol ved st arti ng i n WW1 w hen US obtained UK 8” howitzers • 8” cannons right up to the this timeframe were of the same basic design • Well liked byyyppyy soldiers for accuracy, firepower, simplicity, reliability • Enormous supply of 8” ammunition in stockpile • ‘New’ design of the 175 MM borrowed heavily from this basic design 8”8” HowitzerM110 Howitzer Model showingof 1917 Vickersbreech Markand tube VII (1)(2) circa 1965 3 Background – Requirements Development of 175 MM M107 Howitzer ISO 9001 Certified FS15149 • 175 MM Cannon Overview and Fielding (cont’d) – Performance of the 175 MM • MlMuzzle ve litlocity 3000 fps -

CINCPAC Bulletin 152-45, Japanese Artillery Weapons

RESTRICTED UNITED STATES PACIFIC FLEET AND PACIFIC OCEAN AREAS JAPANESE ARTILLERY WEAPONS CINCPAC - CINCPOA BULLETIN NO. 152-45 1 JULY 1945 CINCPAC-CINCPOA BULLETIN 152-45 1 JULY 1-945 A>rtdle/uf 'Wea/panA Foreword This publication is a summary of the characteristics an recognition features of all Japanese artillery weapons for which information is available. Some weapons are not included because information regarding them is extremely limited and has not been substantiated. Information has been compiled from various sources and includes only pertinent data. Detailed information on specific weapons will be furnished on request. Correc tions and additions will be made from time to time, and recipients are invited to forward additional data to the Joint Inte lligence Center, Pacific Ocean Areas. Additional copies are available on request. This supersedes CIPCPAC-CIHCPOA Bulletin 26-45. RESTRICTED. JAPANESE ARTILLERY WEAPONS. RESTRICTED. CINCPAC-CINCPOA BULLETIN 152-4 5. 1 JULY 194 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS 75 mm Mountain Gun Type 41 (1908) 2 75 mm Mountain Gun Type 94 (1934) 4 75 nun Field Gun Type 38 (1905) 6 75 nun Field Gun Type 33 (Improved) 0 75 mm Field Gun Type 90 (1930) 10 75 mm Field Gun Type 95 (1935) 12 105 mm Howitzer Type 91 (1931) 14 105 mm Gun Type 38 (1905) 16 105 mm Gun 14th Year Type (1925) 18 105 mm Gun Type 92 (1932) 20 ,120 wn Howitzer Type 38 (1905) 22 150 mm Howitzer 4th Year Type (1915) 24 150 mm Howitzer Type 96 (1936) 26 150 nm Gun Type 89 (1929) 28 75 mm Anti-Aircraft Gun Type 88- (1928) 30 8 cm Dual Purpose Gun 10th Year Type (1921) 32 8 cm Coast Defense Gun 13th Year Type (1924) 34 88 mm Anti-Aircraft Gun Type 99 (1939) 36 10 cm Dual Purpose Gun Type 98 (1938) 38 105 mm Anti-Aircraft Gun 14th Yea^ Type (1925) 40 12 cm Short Naval Gun 42 12 cm Dual Purpose Gun 10th Year Type (1921) 44 JAPANESE ARTILLERY WEAPONS. -

STANDARDS for HISTORIC WEAPONS USE Revised September 2018

MARYLAND PARK SERVICE STANDARDS FOR HISTORIC WEAPONS USE Revised September 2018 Maryland Park Service Revised, September 2018 Standards for Historic Weapons Use MARYLAND PARK SERVICE STANDARDS FOR HISTORIC WEAPONS USE Revised September 2018 Table of Contents Purpose ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Definitions................................................................................................................................................ 3 Rules and Roles for the Historic Weapons Safety Committee, Instructors and Officers ......................... 4 Universal Standards for All Historic Weapons Demonstrations .............................................................. 5 Rules for Non-Firing Demonstrations ...................................................................................................... 7 Rules for Edged Weapons and Tools ....................................................................................................... 7 Rules for Small Arms Demonstrations (Infantry and Cavalry) ............................................................... 8 Rules for Artillery Demonstrations ........................................................................................................ 10 Appendix A: Range for Small Arms Blank Firing................................................................................. 14 Appendix B: Range for Blank Cannon Firing ...................................................................................... -

105Mm Howitzer M2 Series Towed

MII Copy 3w S b DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY FIELD MANUAL REGRADEO UNCLASSIFIED By AU'.TY 1O00 DIR. 5200. 1 r 105 - nm HOWITZER M2 - SERIES TOWED DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY * AUGUST 1952 -- UNCLASSIFIED DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY FIELD MANUAL FM 6-75 This manual supersedes FM 6-75, 5 October 1945, including C1, 24 January 1947 105 - mm HOWITZER M2 - SERIES TOWED DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY · AUGUST 1952 United States Government Printing Office Washington : 1952 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY WASHINGTON 25, D. C., 7 August 1952 FM 6-75 is published for the information and guidance of all concerned. lAG 300.7 (28 Jun 52)] BY ORDER OF THE SECRETARY OF THE ARMY: OFFICIAL: J. LAWTON COLLINS WM. E. BERGIN Chief of Staff Major General, USA United States Army The Adjutant General DISTRIBUTION: Active Army: Tech Svc (1); Tech Svc Bd (2); AFF (10); AA Comd (2); OS Maj Comd (10); Base Comd (5); MDW (2); Log Comd (2); A (2); CHQ (2); Div (5); Brig 6 (2); Regt 6 (2); USMA (5); C & GSC (2); Sch (2) except 6 (500); RTC 6 (100); FT (1); PRGR 9 (2); T/O & E's: 6-25N (25); 6-225 (25). NG: Div (2); Brig .6 (2); Regt 6 (2); T/O & E 6-25N (2), 6-225 (2). ORC: Div (2); Brig 6 (2); Regt 6 (2); T/O & E 6-25N (2), 6-225 (2). For explanation of distribution formula, see SR 310-90-1. CONTENTS Paragraphs Page CHAPTER 1. GENERAL .................... 1- 3 1 2. ORGANIZAT:ON ............... 4, 5 5 CHAPTER 3. -

Residual Dinitrotoluenes from Open Burning of Gun Propellant

Chapter 21 Residual Dinitrotoluenes from Open Burning of Gun Propellant Emmanuela Diaz,* Sylvie Brochu, Isabelle Poulin, Dominic Faucher, André Marois, and Annie Gagnon Energetic Materials Section, Defence Research and Development Canada-Valcartier, 2459 Pie-XI Blvd North, Quebec (Qc) G3J 1X5, Canada *[email protected] Following military live fire artillery training, excess propellant bags are routinely open-burned at the firing site. Combustion of these propellants are typically incomplete under these conditions in the field, resulting in residues deposited on the soil surface, such as nitroglycerine and dinitrotoluenes. To better assess the amount of contaminants released during this process, burning tests were conducted with propellant bags from 105- and 155-mm munitions used for howitzer guns. Three different “activities” or burning tests were performed to achieve this study, which are described here. Residual 2,4- and 2,6-dinitrotoluene (DNTs) were analysed in all collected samples. Downloaded by Brian Salvatore on January 4, 2015 | http://pubs.acs.org Publication Date (Web): November 21, 2011 | doi: 10.1021/bk-2011-1069.ch021 Introduction At the end of most military exercises involving large caliber ammunition, such as 105- and 155-mm howitzers, trainees are usually left with a surplus quantity of unused gun propellant. Propellant charges for various large caliber ammunition are supplied in bags of known propellant quantity, from which a certain number are chosen for selective targeting at various distances. Propellant bags not used during the training exercise are destroyed on-site by open burning. For example, the firing of 30,000 rounds of 105-mm ammunition results in the burning of approximately 20,000 kg of single base propellant. -

Wear and Erosion in Large Caliber Gun Barrels

UNCLASSIFIED/UNLIMITED Wear and Erosion in Large Caliber Gun Barrels Richard G. Hasenbein Weapon Systems & Technology Directorate Armament Engineering & Technology Center U.S. Army Armament Research, Development & Engineering Center Mailing Address: Benét Laboratories Watervliet Arsenal Watervliet NY 12189-4050 [email protected] PREFACE “Wear and erosion” is one of several failure mechanisms that can cause large caliber Gun Barrels to be condemned and removed from service. This paper describes the phenomenon, its causes and effects, methods that are used to passively manage it, and steps that are taken to actively mitigate it. 1.0 GUN BARRELS – BACKGROUND A large caliber Cannon (Figure 1) is a pressure vessel whose primary function is to accurately fire projectiles at high velocities towards a target. Figure 1: Representative Large Caliber Cannon At its simplest, a Cannon consists of two major sub-assemblies: • “Gun Barrel”: a long, slender Tube that serves multiple functions such as safely containing high pressure combustion gases and providing a means for aiming/guiding the projectile in the intended direction; • “Breech”: an assembly that seals off the rear of the Gun Barrel during firing, but which can be quickly opened to allow loading of ammunition. It also contains a device used to initiate the combustion process. Paper presented at the RTO AVT Specialists’ Meeting on “The Control and Reduction of Wear in Military Platforms”, held in Williamsburg, USA, 7-9 June 2003, and published in RTO-MP-AVT-109. RTO-MP-AVT-109 16 - 1 UNCLASSIFIED/UNLIMITED UNCLASSIFIED/UNLIMITED Wear and Erosion in Large Caliber Gun Barrels 1.1 GUN BARREL INTERNAL GEOMETRY Internally, a Gun Barrel often features three distinct regions (Figure 2): • “bore”: a long cylindrical hole machined to exacting tolerances for diameter, axial straightness, and surrounding wall thickness; • “combustion chamber”: a much shorter hole at the breech-end of the Gun Barrel that is coaxial with the bore and has a slightly larger diameter. -

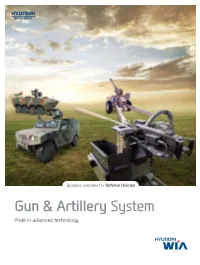

Gun & Artillery System

Business overview for Defense Division Gun & Artillery System Pride in advanced technology People-Oriented Human Mechatronics ! HYUNDAI WIA will open our living future along with nature HYUNDAI WIA is now making a lot of exertions for improving our happiness through High Technology And HYUNDAI WIA is developing various Social Volunteer Activities in order to fulfill our obligation, contribution to our society Human Mechatronics World which HYUNDAI WIA is seeking after is affluent human society construction living with nature and giving priority to human. 01HYUNDAI WIA Gun & Armament K2/K1A1 120mm Tank Gun K9 155mm Self-propelled Howitzer Main Armament K9 Characteristics • Longer range, higher rate of fire and more accurate fire •Large multiple slotted muzzle brake •Fume evacuator •Vertically sliding breech mechanism •High strength obturator ring •K2 120mm Tank Gun •K1A1 120mm Tank Gun •Automatic primer feeding magazine • Constant, hydro-pneumatic, independent recoil mechanism Characteristics •Thermal warning device • Fitted on K2 and K1A1 MBT •Automatic projectile loading system • Concentric recoil mechanism • Fume evacuator Specifications • Vertically sliding breech mechanism K2 Breech Opening Motor • High rigidity cradle Model K9 Caliber 155mm Barrel Length 52 Caliber Max. Firing Range 40Km K2 Main Gun Controller Rate of Fire(Max.) 6rds/min (3min) Specifications Rate of Fire(Sustained) 2rds/min (60min) Primer Feeding System Automatic (Revolver Type) Model K2 K1A1 Caliber 120mm 120mm Barrel Length 55 Caliber 44 Caliber Eff. Firing Range -

Citizen-Soldier Magazine Issue 4 Vol 1

A Resource for the Soldiers and Families of the Army National Guard Citizen-Soldier CITIZEN-SOLDIERMAGAZINE.COM ISSUE 4 // VOL 1 Pennsylvania and Tennessee Soldiers Master Qualifications as Joint Members of the 278th Armored Cavalry Regiment | Page 22 TRICARE Dental BRIDGING THE GAP Take Advantage of Affordable South Carolina Army National Guard Dental Care That Can Help You Keep Champions the New Army National Compliant With Your PHA | Page 44 Guard Patriot Training Program | Page 6 page 6 MEMORIAL DAY CELEBRATE HONOR REMEMBER MAY 28, 2018 FEATURES BRIDGING THE GAP 6 The South Carolina Army National Guard’s 263rd Army Air Missile Defense Command is bridging the information gap as they prepare Soldiers for battle with the new Army National Guard Patriot Training Program. A REAL CALL OF DUTY 11 A former Army National Guard Soldier and World War II Veteran uses his action- packed memory from the past to help shape the scenery of a newer generation’s national pastime. (GUARD) MAN’S BEST FRIEND 19 Read one Soldier’s story of how she came to the rescue of a four-legged evacuee, searching for help in the aftermath of a natural disaster. FORTIFIED THROUGH TEAMWORK 22 Soldiers from the 278th Armored Cavalry Regiment use collaboration ISSUE 4 | VOL 1 and perseverance to complete qualification training in preparation for both NTC and an upcoming deployment to the Middle East. DELTA DELUGE 27 The Arkansas Army National Guard responds with speed and fervor to record-breaking and potentially recurring floods in the Northeast section of the State. FACILITATING EDUCATION – BYPASSING DEBT 39 The Idaho Army National Guard spotlights three Soldiers and how they used the National Guard Tuition Assistance Program to create their own legacy of education – debt-free. -

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605 A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew de la Garza Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin, Advisor; Stephen Dale; Jennifer Siegel Copyright by Andrew de la Garza 2010 Abstract This doctoral dissertation, Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, examines the transformation of warfare in South Asia during the foundation and consolidation of the Mughal Empire. It emphasizes the practical specifics of how the Imperial army waged war and prepared for war—technology, tactics, operations, training and logistics. These are topics poorly covered in the existing Mughal historiography, which primarily addresses military affairs through their background and context— cultural, political and economic. I argue that events in India during this period in many ways paralleled the early stages of the ongoing “Military Revolution” in early modern Europe. The Mughals effectively combined the martial implements and practices of Europe, Central Asia and India into a model that was well suited for the unique demands and challenges of their setting. ii Dedication This document is dedicated to John Nira. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Professor John F. Guilmartin and the other members of my committee, Professors Stephen Dale and Jennifer Siegel, for their invaluable advice and assistance. I am also grateful to the many other colleagues, both faculty and graduate students, who helped me in so many ways during this long, challenging process.