Read Ellington West Memphis Three 6O Million Docx for Kindle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Representations of the Moors Murderers and Yorkshire Ripper Cases

CULTURAL REPRESENTATIONS OF THE MOORS MURDERERS AND YORKSHIRE RIPPER CASES by HENRIETTA PHILLIPA ANNE MALION PHILLIPS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History, and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis examines written, audio-visual and musical representations of real-life British serial killers Myra Hindley and Ian Brady (the ‘Moors Murderers’) and Peter Sutcliffe (the ‘Yorkshire Ripper’), from the time of their crimes to the present day, and their proliferation beyond the cases’ immediate historical-legal context. Through the theoretical construct ‘Northientalism’ I interrogate such representations’ replication and engagement of stereotypes and anxieties accruing to the figure of the white working- class ‘Northern’ subject in these cases, within a broader context of pre-existing historical trajectories and generic conventions of Northern and true crime representation. Interrogating changing perceptions of the cultural functions and meanings of murderers in late-capitalist socio-cultural history, I argue that the underlying structure of true crime is the counterbalance between the exceptional and the everyday, in service of which its second crucial structuring technique – the depiction of physical detail – operates. -

BOARD REPORT January 2021

BOARD REPORT January 2021 FARM During the month of December, steers from both farms were RESEARCH/PLANNING sold through Superior Livestock at a good price and were shipped out prior to Christmas. All heifers are being held as possible December 2020 Admissions and Releases – Admissions for replacements for the coming year. December 2020 totaled 468 (402-males and 66-females) while releases totaled 522 (449-males and 73 females) for a net decrease Greenhouses are being finished out at units across the state in in-house of 54 inmates. preparation of being operational by spring. Inmate Population Growth/Projection – At the end of December Thirty head of dairy cattle were purchased from an Arkansas 2020, the jurisdictional population for the Division of Correction dairy. A total of 15 are fresh milking and the remaining half are totaled 16,094, representing a decrease of 1,665 inmates since the springing heifers. This purchase has already increased the milk first of January 2020. Calendar year 2020 has seen an average decrease production for Farm Operations. of 139 inmates per month, which is up from an average monthly In anticipation of planting the 2021 crops, row crop crews decrease of three inmates per month during calendar year 2019. worked in the shops preparing equipment. Average County Jail Back-up – The backup in the county jails averaged 1,853 inmates per day during the month of December REGIONAL MAINTENANCE HOURS 2020, which was down from the per-day average of 1,986 inmates Regional Maintenance Hours December 2020 during the month of November 2020. -

In the Circuit Court of Crittenden County First Division

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF CRITTENDEN COUNTY FIRST DIVISION STATE OF ARKANSAS PLAINTIFF/RESPONDENT v. No. 18CR-93-516 DAMIEN ECHOLS DEFENDANT/PETITIONER MOTION FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF Having recently learned of the West Memphis Police Department’s (“WMPD”) spoliation of evidence in his case, apparently both before and after his Alford plea, Damien Echols moves this Court to exercise its continuing supervi- sory jurisdiction over this case to declare the violation of his rights by this miscon- duct and to enjoin its continuation pending the development of a full factual record upon which the Court can consider awarding appropriate relief to Echols for the damages it has caused him. As grounds for this motion, Echols asserts the follow- ing: Background 1. Echols was one of three teenagers tried and convicted of killing three young boys in the infamous West Memphis Three case. Echols was sentenced to death as a result of his murder convictions. Throughout the proceedings, Echols and his co-defendants Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley, Jr. (collectively “the WM3”) maintained their innocence of the crimes. 1 2. Over the course of the eighteen years following the murders, and con- sistent with their claims of innocence, the WM3 pursued numerous factual and le- gal challenges to the convictions. In connection with one of those challenges, in November 2010, the Arkansas Supreme Court ordered the trial court to hold a hearing to consider whether newly analyzed DNA evidence might exonerate the WM3. Ultimately, the development of further evidence in anticipation of that hearing - including the results of additional new DNA testing of certain evidence - led the parties to negotiate an Alford plea resolution of the cases, enabling the WM3 to maintain their innocence while being immediately released from prison. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

West of Memphis

Mongrel Media Presents WEST OF MEMPHIS A film by Amy Berg (146 min., USA, 2012) Language: English Official Selection Sundance Film Festival 2012 Toronto Film Festival 2012 Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1028 Queen Street West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html WEST OF MEMPHIS Synopsis A new documentary written and directed by Academy Award nominated filmmaker, Amy Berg (DELIVER US FROM EVIL) and produced by first time filmmakers Damien Echols and Lorri Davis, in collaboration with the multiple Academy Award winning team of Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh, WEST OF MEMPHIS tells the untold story behind an extraordinary and desperate fight to bring the truth to light; a fight to stop the State of Arkansas from killing an innocent man. Starting with a searing examination of the police investigation into the 1993 murders of three, eight year old boys Christopher Byers, Steven Branch and Michael Moore in the small town of West Memphis, Arkansas, the film goes on to uncover new evidence surrounding the arrest and conviction of the other three victims of this shocking crime – Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley. All three were teenagers when they became the target of the police investigation; all three went on to lose 18 years of their lives - imprisoned for crimes they did not commit. How the documentary came to be, is in itself a key part of the story of Damien Echols’ fight to save his own life. -

February 2012

THE A DVOCATE A PUBLICATION OF THE ARKANSAS DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTION February 2012 Inside this issue ; Director‘s Corner 2 ADC mourns loss of officer Department Briefs 2 Class 2011-O Graduates 3 Cpl. Ester killed by Class 2012-P Graduates 3 inmate at EARU Cartoon 3 3 SSCA Raises Bar 4 ADC, AACET in KY 4 Health Matters/ 5 Back Pain Prevention Farewell to Diagnostic 6 COEA Chili Cook-Off 7 Policy Spotlight 7 Inmate Drama Group 8 Frank Ellis 8 Severe Weather Damage 9 Weight Management 10 Three Generation ADC 10 On Jan. 20, Cpl. Barbara Ester died crowd flowed into the lobby and outside. after being attacked by an inmate at the The crowd was so large that ADC Retiring 10 East Arkansas Regional Unit at Brickeys. employees gave up their seats to allow New U.S. Citizens 11 She was performing duties as a property space for family and community mem- Calendar of Events 11 officer when she suffered stab wounds to bers to be seated. the chest area. Representatives from corrections and Mailroom Terrorism 12 Cpl. Ester died later that afternoon in law enforcement organizations across the A year later 12 a Memphis hospital. country attended. Sgt. Laurel Hooks of Chaplain on Gun Range 13 She was a well loved and respected the Tucker Unit Boot Camp program or- officer at East Arkansas and was known ganized the honor guard for Cpl. Ester‘s Polar Bear Plunge/Run 13 as a generous person with a big heart in service. Officers came from prisons and Training Information 14 her community and church in Marianna. -

EXHIBIT a (Part 6) EXHIBIT A-51 • West Memphis Three DNI --Ilts Page 1 Of2

EXHIBIT A (Part 6) EXHIBIT A-51 • West Memphis Three DNI --ilts Page 1 of2 ~.com~ mphis Teresa's Memphis Blog By Teresa R. Simpson, About.com West Memphis Three DNA Results Friday July 20, 2007 Fourteen years ago, three little boys were brutally murdered in West Memphis, Arkansas. Shortly thereafter, three teenage boys were convicted of the crime. The convicted boys are grown men now and are all in prison. One of them ison death row. Several weeks ago, however, a team of investigators assembled to study DNA evidence in the Wes.LI':1~mp-bj~,-3..case. Now, the results of that investigation are in. No DNA evidence was found that linked Jessie Misskelly, Damien Echols, or Jason Baldwin to the crime. Instead, hair belonging to the stepfather of Stevie Branch (one of the victims) was found amongst the evidence. Though it is unclear what effect this evidence will have on the status of the case, defense attorneys for the ~l\'-e.s.t.M~j~.3.~ that it will result in a new trial. Comments (1) Jason Ringwald says: July 20, 2007 at 5:58 pm Everybody who wasn't blinded by prejudice new that those guys didn't do it. They were convicted because they looked different from everyone else. Plus a lot of people always suspected the stepfather. (2) Laurel says: August 4,2007 at 8:18 am Yes, a lot of folks (including the folks who shot both Paradise Lost doccos) suspected Christopher Byers' stepfather of the crime, NOT Stevie Branch's (whose name, I think, is Terry Hobbs). -

Annual Report 2018

ARKANSAS DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTION ANNUAL REPORT FY 2018 Arkansas Department of Correction FY18 Annual Report Table of Contents Mission Statement Provide public safety by carrying out the mandates of the courts; provide a safe, humane environment for Director‘s Message………………………. 3 staff and inmates; provide programs to strengthen the Organizational ….……………………….. 4 work ethic; provide opportunities for spiritual, mental and physical growth. Personnel………………………………… 5 Highlights……………………………….. 6-13 Vision Statement Accreditation…....………………………. 14 To be an honorable and professional organization through ethical and innovative leadership at all Fiscal Summary………………………….. 15 levels, providing cost efficient, superior correctional services that return productive people Admissions………………………………. 16-17 to the community. Releases…………………………………. 18 Core Values Population Snapshot…………………….. 19-25 Honor ADC Programs………………………….. 26-33 Integrity Public Service ADC Facilities…………………………... 34-55 Accountability Transparency Acknowledgement……………………….. 56 Goals To maintain cost-efficient care and custody of all inmates. To provide appropriate facilities for inmates sen- tenced by the courts. To provide constructive correctional opportunities that will help inmates successfully return to their communities. To optimize inmate assignments in work programs. To attract and retain quality staff. Transparency. 2 Director’s Letter As Director, it is with sincere pride that I present you with the Arkansas Department of Correction (ADC) Fiscal Year 2018 Annual Report, as required by Ark. Code Ann. 12-27-107. During the fiscal year, the Arkansas Department of Correction jurisdictional count remained at, or near, 18,000 inmates. Our continued implementation of the Think Legacy Reentry Program, college programs, and workforce readiness programs will reduce the number of inmates returning to incarceration after release. During this fiscal year, we also began the construction of additional beds at the Pine Bluff Unit. -

On the Challenges of the Alford Plea by Lloyd Liu

ON FURTHER REVIEW On the Challenges of the Alford Plea By Lloyd Liu his column has mentioned declining to bring ill-founded charges with the In November 2010, the Arkansas Supreme stroke of his pen. The best a criminal defense Court granted the defendants’ request for an the vanishing trial and its impli- lawyer can do is try to talk people out of evidentiary hearing to determine whether to cations. There are fewer trials potential guilt one charge at a time. And that’s have a new trial.7 Braga took that development T a much slower process than the prosecutor’s as an opportunity to talk the prosecutor out for a multitude of reasons, some ability to not bring charges in the first place.” of pursuing the charges any further. Despite the significant new evidence, the state more troubling than others. In 2009, while at Ropes & Gray LLP, Braga began remained steadfast in its desire to retry the pro bono representation of Damien Echols of West Memphis Three. Braga persisted, however, Defense attorney Stephen Braga the West Memphis Three. Echols, Jessie and negotiated an agreement for Echols to Misskelley Jr., and Jason Baldwin were charged recently discussed with me maintain his innocence but also plead guilty with the brutal murder of three eight-year-old via the compromise device of an Alford plea. his experience with the West boys in the early 1990s in West Memphis, Memphis Three in which the Arkansas.1 The investigation and trial were The situation reminded Braga of Judge plagued with a litany of issues: a suspicious Flannery’s advice about prosecutorial circumstances made getting confession, speculation over a satanic cult, discretion: and questionable forensics work, among a new trial essentially impossible. -

Video-Windows-Grosse

THEATRICAL VIDEO ANNOUNCEMENT TITLE VIDEO RELEASE VIDEO WINDOW GROSS (in millions) DISTRIBUTOR RELEASE ANNOUNCEMENT WINDOW DISNEY Fantasia/2000 1/1/00 8/24/00 7 mo 23 Days 11/14/00 10 mo 13 Days 60.5 Disney Down to You 1/21/00 5/31/00 4 mo 10 Days 7/11/00 5 mo 20 Days 20.3 Disney Gun Shy 2/4/00 4/11/00 2 mo 7 Days 6/20/00 4 mo 16 Days 1.6 Disney Scream 3 2/4/00 5/13/00 3 mo 9 Days 7/4/00 5 mo 89.1 Disney The Tigger Movie 2/11/00 5/31/00 3 mo 20 Days 8/22/00 6 mo 11 Days 45.5 Disney Reindeer Games 2/25/00 6/2/00 3 mo 8 Days 8/8/00 5 mo 14 Days 23.3 Disney Mission to Mars 3/10/00 7/4/00 3 mo 24 Days 9/12/00 6 mo 2 Days 60.8 Disney High Fidelity 3/31/00 7/4/00 3 mo 4 Days 9/19/00 5 mo 19 Days 27.2 Disney East is East 4/14/00 7/4/00 2 mo 16 Days 9/12/00 4 mo 29 Days 4.1 Disney Keeping the Faith 4/14/00 7/4/00 2 mo 16 Days 10/17/00 6 mo 3 Days 37 Disney Committed 4/28/00 9/7/00 4 mo 10 Days 10/10/00 5 mo 12 Days 0.04 Disney Hamlet 5/12/00 9/18/00 4 mo 6 Days 11/14/00 6 mo 2 Days 1.5 Disney Dinosaur 5/19/00 10/19/00 5 mo 1/30/01 8 mo 11 Days 137.7 Disney Shanghai Noon 5/26/00 8/12/00 2 mo 17 Days 11/14/00 5 mo 19 Days 56.9 Disney Gone in 60 Seconds 6/9/00 9/18/00 3 mo 9 Days 12/12/00 6 mo 3 Days 101.6 Disney Love’s Labour’s Lost 6/9/00 10/19/00 4 mo 10 Days 12/19/00 6 mo 10 Days 0.2 Disney Boys and Girls 6/16/00 9/18/00 3 mo 2 Days 11/14/00 4 mo 29 Days 21.7 Disney Disney’s The Kid 7/7/00 11/28/00 4 mo 21 Days 1/16/01 6 mo 9 Days 69.6 Disney Scary Movie 7/7/00 9/18/00 2 mo 11 Days 1212/00 5 mo 5 Days 157 Disney Coyote Ugly 8/4/00 11/28/00 3 -

Eric Vespe from Aintitcool.Com Recently Sat Down with Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens to Discuss Their Documentary, WEST of MEMPHIS

Eric Vespe from aintitcool.com recently sat down with Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens to discuss their documentary, WEST OF MEMPHIS. (The following is excerpted from the full article available at: http://www.aintitcool.com/node/52167) Eric Vespe: As someone who followed Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky’s Paradise Lost series, I’ve long been fascinated (and frustrated) by the case of The West Memphis Three… If you haven’t seen the Berlinger/Sinofsky documentaries or know much of anything about the case, the rundown is: In the early ‘90s, three young boys were murdered in a small Arkansas town. Three local teens were arrested and tried for the crimes and, based on questionable evidence, convicted. After 18 years in prison, the three men—Jessie Misskelley, Jason Baldwin and Damien Echols—were set free in a complicated plea deal in which the State of Arkansas did not acknowledge their innocence. This case is rife with controversy... As it should be. It’s my opinion that these three men are innocent and I’m not alone. Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens recently revealed that they had contributed to the defense of the West Memphis Three, and I’ve come to discover that they had a big hand in funding the search for and uncovering new DNA evidence that proved critical to their release. While keeping a rather low profile about their exact involvement, they recently announced that they have completed work on a documentary about the case called WEST OF MEMPHIS, produced by Jackson and Walsh and directed by Amy Berg (DELIVER US FROM EVIL). -

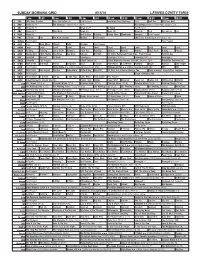

Sunday Morning Grid 8/14/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/14/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Incredible Dog Challenge Paid Golf Res. PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Rio Olympics Track and Field. (N) Å Rio Olympics Women’s Basketball: China vs. U.S. 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 2016 U.S. Senior Open Final Round. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Mom Mkver Church Faith Dr. John Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Eat Dirt-Axe 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage (TV14) Å Leverage (TV14) Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Tigres República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Home Alone 3 › (1997, Comedia) Alex D.