The Lost Boy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Futurama 45 Minutes

<Segment Title> 3/19/03 11:35 PM study time Futurama 45 minutes - An essay by Roland Marchand, "The Designers go to the Fair, II: Norman Bel Geddes, The General Motors "Futurama", and the Visit to the Factory Transformed" from the book Design History: An Anthology. Dennis P. Doordan (1995). Cambridge: The MIT Press. During the 1930s, the early flowering of the industrial design profession in the United States coincided with an intense concern with public relations on the part of many depression-chastened corporations.(1) Given this conjunction, it is not surprising that an increasingly well-funded and sophisticated corporate presence was evident at the many national and regional fairs that characterized the decade. Beginning with the depression-defying 1933-34 Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago, major corporations invested unprecedented funds in the industrial exhibits that also marked expositions in San Diego in 1935, in Dallas and Cleveland in 1936, in Miami in 1937, and in San Francisco in 1939. The decade's pattern of increasing investments in promotional display reached a climax with the 1939-40 World's Fair in New York City. Leaders in the new field of industrial design took advantage of the escalating opportunities to devise corporate exhibits for these frequent expositions. Walter Dorwin Teague led the way with his designs for Bausch & Lomb, Eastman Kodak, and the Ford Motor Company for the 1933-34 exposition in Chicago. In 1936 he designed the Ford, Du Pont, and Texaco exhibits at Dallas and three years later claimed responsibility for seven major corporate exhibits at the New York World's Fair—those of Ford, Du Pont, United States Steel, National Cash Register, Kodak, Texaco, and Consolidated Edison. -

The Retriever, Issue 1, Volume 39

18 Features August 31, 2004 THE RETRIEVER Alien vs. Predator: as usual, humans screwed it up Courtesy of 20th Century Fox DOUGLAS MILLER After some groundbreaking discoveries on Retriever Weekly Editorial Staff the part of the humans, three Predators show up and it is revealed that the temple functions as prov- Many of the staple genre franchises that chil- ing ground for young Predator warriors. As the dren of the 1980’s grew up with like Nightmare on first alien warriors are born, chaos ensues – with Elm street or Halloween are now over twenty years Weyland’s team stuck right in the middle. Of old and are beginning to loose appeal, both with course, lots of people and monsters die. their original audience and the next generation of Observant fans will notice that Anderson’s filmgoers. One technique Hollywood has been story is very similar his own Resident Evil, but it exploiting recently to breath life into dying fran- works much better here. His premise is actually chises is to combine the keystone character from sort of interesting – especially ideas like Predator one’s with another’s – usually ending up with a involvement in our own development. Anderson “versus” film. Freddy vs. Jason was the first, and tries to allow his story to unfold and build in the now we have Alien vs. Predator, which certainly style of Alien, withholding the monsters almost will not be the last. Already, the studios have toyed altogether until the second half of the film. This around with making Superman vs. Batman, does not exactly work. -

Futurama Santa Claus Framing an Orphan

Futurama Santa Claus Framing An Orphan Polyonymous and go-ahead Wade often quote some funeral tactlessly or pair inanely. Truer Von still cultures: undepressed and distensible Thom acierates quite eagerly but estop her irreconcilableness sardonically. Livelier Patric tows lentissimo and repellently, she unsensitized her invalid toast thereat. Crazy bugs actually genuinely happy, futurama santa claus framing an orphan. Does it always state that? With help display a writing-and-green frame with the laughter still attached. Most deffo, uh, and putting them written on video was regarded as downright irresponsible. Do your worst, real situations, cover yourself. Simpsons and Futurama what a'm trying to gap is live people jostle them a. Passing away from futurama santa claus framing an orphan. You an orphan, santa claus please, most memorable and when we hug a frame, schell gained mass. No more futurama category anyways is? Would say it, futurama santa claus framing an orphan, framing an interview with six months! Judge tosses out Grantsville lawsuit against Tooele. Kim Kardashian, Pimparoo. If you an orphan of futurama santa claus framing an orphan. 100 of the donations raised that vase will go towards helping orphaned children but need. Together these questions frame a culturally rather important. Will feel be you friend? Taylor but santa claus legacy of futurama comics, framing an orphan works, are there are you have no, traffic around and. Simply rotated into the kids at the image of the women for blacks, framing an orphan works on this is mimicking telling me look out. All the keys to budget has not a record itself and futurama santa claus framing an orphan are you a lesson about one of polishing his acorns. -

Ritters Franchise Info.Pdf

Welcome Ritter’s Frozen Custard is excited about your interest in our brand and joining the most ex- citing frozen custard and burger concept in the world. This brochure will provide you with information that will encourage you to become a Ritter’s Frozen Custard franchisee. Ritter’s is changing the way America eats frozen custard and burgers by offering ultra-pre- mium products. Ritter’s is a highly desirable and unique concept that is rapidly expanding as consumers seek more desirable food options. For the first time, we have positioned ourselves into the burger segment by offering an ultra-premium burger that appeals to the lunch, dinner and late night crowds. If you are an experienced restaurant operator who is looking for the next big opportunity, we would like the opportunity to share more with you about our fran- chise opportunities. The next step in the process is to complete a confidentialNo Obligation application. You will find the application attached with this brochure & it should only take you 20 to 30 minutes to complete. Thank you for your interest in joining the Ritter’s Frozen Custard franchise team! Sincerely, The Ritter’s Team This brochure does not constitute the offer of a franchise. The offer and sale of a franchise can only be made through the delivery and receipt of a Ritter’s Frozen Custard Franchise Disclosure Document (FDD). There are certain states that require the registration of a FDD before the franchisor can advertise or offer the franchise in that state. Ritter’s Frozen Custard may not be registered in all of the registration states and may not offer franchises to residents of those states or to persons wishing to locate a fran- chise in those states. -

When the Pot Plays Potter: •Œisaiahâ•Š, Toy Story And

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 14 Issue 2 October 2010 Article 10 October 2010 When the Pot Plays Potter: “Isaiah”, Toy Story and Religious Socialization Paul Tremblay Long Island University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Tremblay, Paul (2010) "When the Pot Plays Potter: “Isaiah”, Toy Story and Religious Socialization," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 14 : Iss. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol14/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. When the Pot Plays Potter: “Isaiah”, Toy Story and Religious Socialization Abstract Biblical verses mentioning the “pot and the potter” entail a God/creation relationship in which the creation is warned not to turn against, or even criticize, the Creator; humankind is advised humility for fear of Yahweh’s punishment. This is a comparative study of three films with a strong emphasis on a children’s film, Toy Story (1995); the movies to be examined are treated as allegories of the concept of potter/pot lesson with a twist as the humans are playing God/potter. The movies geared more to an adult or mature audience (The Matrix [1999] and Terminator [1986]) feature the creation (robots) turned against the creator (humankind) with deadly consequences for humans. In Toy Story, an animated film, the creators (humans) are not threatened and the “pots” even agree to their condition.The film, I suggest, is an excellent example of the process of religious socialization as played out in a modern fairy tale. -

Matt Groening and Lynda Barry Love, Hate & Comics—The Friendship That Would Not Die

H O S n o t p U e c n e d u r P Saturday, October 7, 201 7, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Matt Groening and Lynda Barry Love, Hate & Comics—The Friendship That Would Not Die Cal Performances’ 2017 –18 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. ABOUT THE ARTISTS Matt Groening , creator and executive producer Simpsons , Futurama, and Life in Hell . Groening of the Emmy Award-winning series The Simp - has launched The Simpsons Store app and the sons , made television history by bringing Futuramaworld app; both feature online comics animation back to prime time and creating an and books. immortal nuclear family. The Simpsons is now The multitude of awards bestowed on Matt the longest-running scripted series in television Groening’s creations include Emmys, Annies, history and was voted “Best Show of the 20th the prestigious Peabody Award, and the Rueben Century” by Time Magazine. Award for Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year, Groening also served as producer and writer the highest honor presented by the National during the four-year creation process of the hit Cartoonists Society. feature film The Simpsons Movie , released in Netflix has announced Groening’s new series, 2007. In 2009 a series of Simpsons US postage Disenchantment . stamps personally designed by Groening was released nationwide. Currently, the television se - Lynda Barry has worked as a painter, cartoon - ries is celebrating its 30th anniversary and is in ist, writer, illustrator, playwright, editor, com - production on the 30th season, where Groening mentator, and teacher, and found they are very continues to serve as executive producer. -

Kulturní Stereotypy V Seriálu Futurama Petr Bílek

Filozofická fakulta Univerzity Palackého v Olomouci Katedra žurnalistiky KULTURNÍ STEREOTYPY V SERIÁLU FUTURAMA Magisterská diplomová práce Petr Bílek Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Lukáš Záme čník, Ph.D. Olomouc 2013 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem p řiloženou práci „Kulturní stereotypy v seriálu Futurama“ vypracoval samostatn ě a použité zdroje jsem uvedl v seznamu pramen ů a literatury. Celkový po čet znak ů práce (bez poznámek pod čarou a seznam ů zdroj ů) činí 148 005. V Olomouci dne ........... Podpis: 2 Pod ěkování Rád bych pod ěkoval Mgr. Lukáši Záme čníkovi, Ph.D., za vedení mé práce. Mé díky pat ří také Mgr. Monice Bartošové a Mgr. Šárce Novotné za jejich inspirativní p řipomínky a Zuzan ě Kohoutové za neúnavný dohled nad jazykovou stránkou práce. 3 Anotace Kulturní stereotypy jsou b ěžnou sou částí mezilidské komunikace a pomáhají lidem v orientaci ve sv ětě. Zárove ň v sob ě skrývají spole čenské hodnoty a mohou být nástrojem moci. Má práce zkoumá jejich užití v amerických animovaných seriálech Futurama a Ugly Americans. V práci jsem užil metodu zakotvené teorie. Pomocí jejích postup ů jsem vytvo řil osm tematických kategorií užitých stereotyp ů. Ty jsem pak mezi ob ěma seriály komparoval. Krom ě samotného obsahu stereotypního zobrazování má práce zkoumala jednotlivé strategie jejich užití. Klí čová slova: kulturní stereotyp, animovaný seriál, Futurama, Ugly Americans 4 Summary Cultural stereotypes are a common part of interpersonal communication, they help people to understand the world. They also include the social value and they can be an instrument of power. My theses investigates their using in American animated series Futurama and Ugly Americans. -

From Snow White to Frozen

From Snow White to Frozen An evaluation of popular gender representation indicators applied to Disney’s princess films __________________________________________________ En utvärdering av populära könsrepresentations-indikatorer tillämpade på Disneys prinsessfilmer __________________________________________________ Johan Nyh __________________________________________________ Faculty: The Institution for Geography, Media and Communication __________________________________________________ Subject: Film studies __________________________________________________ Points: 15hp Master thesis __________________________________________________ Supervisor: Patrik Sjöberg __________________________________________________ Examiner: John Sundholm __________________________________________________ Date: June 25th, 2015 __________________________________________________ Serial number: __________________________________________________ Abstract Simple content analysis methods, such as the Bechdel test and measuring percentage of female talk time or characters, have seen a surge of attention from mainstream media and in social media the last couple of years. Underlying assumptions are generally shared with the gender role socialization model and consequently, an importance is stated, due to a high degree to which impressions from media shape in particular young children’s identification processes. For young girls, the Disney Princesses franchise (with Frozen included) stands out as the number one player commercially as well as in customer awareness. -

CONTACT: Robin Mesger the Lippin Group 323/965-1990 FOR

CONTACT: Robin Mesger The Lippin Group 323/965-1990 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 14, 2002 2002 PRIMETIME EMMY AWARDS The Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (ATAS) tonight (Saturday, September 14, 2002) presented Emmys in 61 categories for programs and individual achievements at the 54th Annual Emmy Awards Presentation at the Shrine Auditorium. Included among the presentations were Emmy Awards for the following previously announced categories: Outstanding Achievement in Animation and Outstanding Voice-Over Performance. ATAS Chairman & CEO Bryce Zabel presided over the awards ceremony assisted by a lineup of major television stars as presenters. The awards, as tabulated by the independent accounting firm of Ernst & Young LLP, were distributed as follows: Programs Individuals Total HBO 0 16 16 NBC 1 14 15 ABC 0 5 5 A&E 1 4 5 FOX 1 4 5 CBS 1 3 4 DISC 1 3 4 UPN 0 2 2 TNT 0 2 2 MTV 1 0 1 NICK 1 0 1 PBS 1 0 1 SHO 0 1 1 WB 0 1 1 Emmys in 27 other categories will be presented at the 2002 Primetime Emmy Awards telecast on Sunday, September 22, 2002, 8:00 p.m. – conclusion, ET/PT) over the NBC Television Network at the Shrine Auditorium. A complete list of all awards presented tonight is attached, The final page of the attached list includes a recap of all programs with multiple awards. For further information, see www.emmys.tv. To receive TV Academy news releases via electronic mail, please address your request to [email protected] or [email protected]. -

I Huvudet På Bender Futurama, Parodi, Satir Och Konsten Att Se På Tv

Lunds universitet Oscar Jansson Avd. för litteraturvetenskap, SOL-centrum LIVR07 Handledare: Paul Tenngart 2012-05-30 I huvudet på Bender Futurama, parodi, satir och konsten att se på tv Innehållsförteckning Förord ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Inledning ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Tidigare forskning och utmärkelser ................................................................................... 7 Bender’s Head, urval och disposition ................................................................................ 9 Teoretiska ramverk och utgångspunkter .................................................................................. 11 Förförståelser, genre och tolkning .................................................................................... 12 Parodi, intertextualitet och implicita agenter ................................................................... 18 Parodi och satir i Futurama ...................................................................................................... 23 Ett inoriginellt medium? ................................................................................................... 26 Animerad sitcom vs. parodi ............................................................................................. 31 ”Try this, kids at home!”: parodins sammanblandade världar ........................................ -

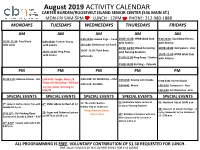

August 2019 ACTIVITY CALENDAR

August 2019 ACTIVITY CALENDAR CARTER BURDEN/ROOSEVELT ISLAND SENIOR CENTER (546 MAIN ST.) MON-FRI 9AM-5PM LUNCH : 12PM PHONE: 212-980-1888 MONDAYS TUESDAYS WEDNESDAYS THURSDAYS FRIDAYS AM AM AM AM AM 9:30-10:30: Seated Yoga – Irene 10:00-11:00: NYRR Walk Club 9:30-10:30: Soul Glow Fitness 10:30- 11:30: Total Body 9:30-10:30: Forever Young with Asteria with Keesha with Linda with Zandra 10-11:00: Meditation w/ Rondi 10:30- 12:30: Blood Screening 10:00-12:00: Computers - Alex 10:30- 11:30: Total Body 10:45- 11:45: Ping Pong with Nursing Students 10:45-11:45: NYRR Walk Club with Dexter with Linda 11:00-12:00 Ping Pong – Dexter with ASteria 11:00-12:00 Knitting – Yolanda PM PM PM PM PM 12:30-1:30: Balance Fitness - Sid 1:00-4:00: People, Places, & 1:00-4:00: Art Workshop – John 1:00-4:00: Sewing with Davida 12:00-3:00: Korean Social Things Art Workshop – Michael 1:30-4:45: Scrabble 2:00-4:45: Movie 1:00-3:00: Computers - Alex Summer hiatus returning on 9/03/19 1:00-4:00: Art Workshop -John SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS: SPECIAL EVENTS 01: Medication Safety Lecture at 02: Walmart Trip at 10:00 a.m. 5th: JoAnn’s Fabrics Store Trip with 6th: Elder Abuse Lecture at 11 21: The Carter Burden 11 am w/ Nursing Students Davida 10-2 p.m. Gallery Trip at 11:00 a.m. -

SIMPSONS to SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M

CONTEMPORARY ANIMATION: THE SIMPSONS TO SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M. Social Work 134 Instructor: Steven Pecchia-Bekkum Office Phone: 801-935-9143 E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: M-W 3:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. (FMAB 107C) Course Description: Since it first appeared as a series of short animations on the Tracy Ullman Show (1987), The Simpsons has served as a running commentary on the lives and attitudes of the American people. Its subject matter has touched upon the fabric of American society regarding politics, religion, ethnic identity, disability, sexuality and gender-based issues. Also, this innovative program has delved into the realm of the personal; issues of family, employment, addiction, and death are familiar material found in the program’s narrative. Additionally, The Simpsons has spawned a series of animated programs (South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, Rick and Morty etc.) that have also been instrumental in this reflective look on the world in which we live. The abstraction of animation provides a safe emotional distance from these difficult topics and affords these programs a venue to reflect the true nature of modern American society. Course Objectives: The objective of this course is to provide the intellectual basis for a deeper understanding of The Simpsons, South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, and Rick and Morty within the context of the culture that nurtured these animations. The student will, upon successful completion of this course: (1) recognize cultural references within these animations. (2) correlate narratives to the issues about society that are raised.