Polychrome Guanaco Cloaks of Patagonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smithsonian Institution

*» ^^^ *c^ N"-/^ ' ;.; »-5 . 3VVVV-O. c "Y^^i f . SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY: J. W. POWELL, DIRECTOR BULLET IN 27 TSTMSHIAN TEXTS FR^IsTZ BO^S WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1 H U -2 CONTENTS Introduction _ o ' Texts: Txii'msEm and Lognl.iolfi' 7 Txii'msEui 25 Txii'msEni _ 36 The Stone and the Elderberry Bnsh 72 Tlie Porcupine and the Beaver 73 The Wolves and the Deer 83 The Stars 86 Rotten-feathers _ 94 K -'eLk" 1 02 The sealion hunters 108 Smoke-hole 116 Ts'ak- 117 Gro\ving-up-like-one-\vho-has-a-irnindniother_ i:!7 Little-eagle 169 She-\vho-has-a-lal)i'et-on-one-side 1S8 The Grizzly Bear 200 Squirrel 211 Witchcraft 217 Supiilementary stories: The origin of the G'ispawailuwE'da 221 Asi-hwi'l 225 The Grouses 229 TsEgu'ksk" 231 Rotten-feathers i continued from page 100) 234 Abstracts 236 3 TSIMSHIAN TEXTS Nass River Dialect Recorded and translated ])y Franz Boas INTRODUCTION The following texts were coUeeted in Kinkolith, at the mouth of the Nass river, during the months of November and December, 189-i, while I was engaged in researches under the auspices of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. The principa] object of these investigations was a study of the Athapascan tribe of Port- land canal, and the following texts were collected incidentally only. The ethnologic results of these investigations were published in the reports of the Committee on the Northwestern Tribes of Canada of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.' The texts are in the Nass River dialect of the Tsimshian language. -

Killer Khilats, Part 1: Legends of Poisoned ªrobes of Honourº in India

Folklore 112 (2001):23± 45 RESEARCH ARTICLE Killer Khilats, Part 1: Legends of Poisoned ªRobes of Honourº in India Michelle Maskiell and Adrienne Mayor Abstract This article presents seven historical legends of death by Poison Dress that arose in early modern India. The tales revolve around fears of symbolic harm and real contamination aroused by the ancient Iranian-in¯ uenced customs of presenting robes of honour (khilats) to friends and enemies. From 1600 to the early twentieth century, Rajputs, Mughals, British, and other groups in India participated in the development of tales of deadly clothing. Many of the motifs and themes are analogous to Poison Dress legends found in the Bible, Greek myth and Arthurian legend, and to modern versions, but all seven tales display distinc- tively Indian characteristics. The historical settings reveal the cultural assump- tions of the various groups who performed poison khilat legends in India and display the ambiguities embedded in the khilat system for all who performed these tales. Introduction We have gathered seven ª Poison Dressº legends set in early modern India, which feature a poison khilat (Arabic, ª robe of honourº ). These ª Killer Khilatº tales share plots, themes and motifs with the ª Poison Dressº family of folklore, in which victims are killed by contaminated clothing. Because historical legends often crystallise around actual people and events, and re¯ ect contemporary anxieties and the moral dilemmas of the tellers and their audiences, these stories have much to tell historians as well as folklorists. The poison khilat tales are intriguing examples of how recurrent narrative patterns emerge under cultural pressure to reveal fault lines within a given society’s accepted values and social practices. -

Home Collection Fall 2016

FALL 2016 HOME COLLECTION RETAIL PRICING TO YOUR WELL-CRAFTED LIFE. MODERN ICONS with classic patterns in sophisticated colors QUALITY CRAFTSMANSHIP with the finest fleece, the finest yarn, the finest blankets AUTHENTIC TEXTILES in contemporary design traditions AMERICAN HERITAGE celebrating America’s Treasures with the Pendleton National Park Collection Special thanks to our brand ambassadors Kristian Irey, Casey Berry, and Our Free Ways for providing images showing Pendleton through their eyes. 5 TH A VENUE T HROWS : 1 0 0 % MERINO WOOL . D RY CLE A N . M ad E IN THE US A . FRINGED THROWS ZB296-53094 Red Stewart ZB296-53095 Black Watch ZB296-52459 Grey Stewart ZB296-53255 Berry Plaid ZB296-50717 Glacier ZB296-52797 Breslin Plaid ZB296-53256 Acadia ZB296-52618 Neutral Stripe ZB296-53253 Charcoal Plaid Not available in Canada. 5th Avenue Throws The ultimate indulgence. Superfine merino wool is softly brushed, producing a fleecy hand that must be touched. The definitive solution for the customer who is looking for an unforgettable gift. 100% merino wool. Dry clean. Made in the USA. 54˝ x 72˝ plus 3˝ fringe (137 x 183 cm + 8 cm). $149 ZB296-53252 Auroral Plaid ZB296-53254 Sandstone Stripe 4 T HROWS : 1 0 0 % MERINO WOOL . D RY CLE A N . M ad E IN THE US A . FRINGED THROWS & HEIRLOOM BLANKETS THROWS FRINGED ZB222-53315 Caspian ZB222-53312 Amethyst ZB222-53313 Ruby ZB222-53314 Amber Cathedral Throw Our new weave captures the intensity of sunlight through stained glass. Subtle ombre effects are created by the play of one color into another. -

Gambling Case Canine Population Gets Big Boost 12 Million Is Added Robe Reveals to Local Assessments O Local Link in Action by County

*f V Newspaper Devoted Complete News, Pictures |he Community Interest Presented Fairly, Clearly Full Local Coverage - leaber And Impartially Each Week Intend at Second Olau Matter WOODBRIDOE, N. J., THURSDAY, JANUARY 20, 1955 Puhllihsd Brtrj Thursday PRICE EIGHT CENTS lit the Pout One*. WnodbrldKt, N. J, •t II Orwn 8tn«t, WnodDrktm, ". ). gambling Case Canine Population Gets Big Boost 12 Million is Added robe Reveals To Local Assessments o Local Link In Action by County , II ,/c arc Held ^olice Chief 7 to Seek 3 School Board 'Equalization' s Questioned Places; Finn is Candidate t Hits Township 4 WOODtiRIDGE—Seven petitions for the three positions open on By Grand Jury the Board of Education were filed In the office of the Secretary of the Board by/line o'clock last night—the deadline for filing. Critical Blow The election will be held Tuesday, February 8. WpODBRIDGE — With Police ,The three incumbents, Harold Van Ness, Colonia; William J Chief John R. Egan the only lo- O'Neill. laelln, and John J. Csabai, Fords, will seek reelection. WOODBRIDGE—In an effort to al w linens called before the Grand equalize the valuations among the Others who filed are Wlnfleld j —7 -™ my yesterday—and then only for 25 Middlesex County municipali- few minutes—Indication* in J. Finn, Woodbrldge; Mrs. Anna ties and to apportion more fairly C. Calvert, Iselin; Elbur Richards, Casey Condition Better; Ww New Brunswick yesterday were the cost of operating the county Woodbridge; John Tobias, Wood- .hat despite the fact that scores of Injured in Car Crash government, the Middlesex: County bridge. -

Daoist Priest's Robe C. 1850–1900 China

This image card shows the back of a beautifully embroidered robe of the type worn by Daoist (DOW-ist) high priests when officiat- ing at religious rites and ceremonies.The robe is filled with images of auspicious symbols of the Daoist religion.Along the bottom edge, dragons frolic in ocean waves, chasing flaming pearls. On the sleeve borders, sets of three lines, known as trigrams, represent the changing forces of nature. Between them are emblems of Daoist Immortals, beings who attained immortality through their Daoist practice.These emblems include: a flower basket for a female immortal who became a fairy after eating a magical peach; a sword for a scholar who had supernatural powers over evil and sickness; musical clappers for the patron saint of theater; and a pair of gourds for a beggar who was able to make his spirit leave his body. Six large medallions in the center of the robe contain elaborately embroidered decorations of animals, plants, and celestial forma- Daoist Priest’s tions.A tower and three small palaces, home to Daoist gods, are Robe depicted in the top central circle.These decorative elements and the twenty-four multicolored dots represent the twenty-eight c. 1850–1900 Lunar Mansions (or constellations), where the moon rests as it journeys around the Earth each month.The moon (right) and China sun (left) can be seen just above the center circle. Inside the moon, (Qing Dynasty, 1644–1911) a rabbit mixes the elixir of immortality; the crow, another deity, lives in the sun.White cranes, like the ones flanking the tower, are closely associated with Daoist priests, who were said to ride the Embroidered silk satin tall birds to the heavens and speak with the gods. -

The Evolution of Cassock, Gown, Habit and Hood As Academic Dress

Transactions of the Burgon Society Volume 5 Article 5 1-1-2005 Layer upon Layer: The Evolution of Cassock, Gown, Habit and Hood as Academic Dress Alex Kerr University of Oxford Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/burgonsociety Recommended Citation Kerr, Alex (2005) "Layer upon Layer: The Evolution of Cassock, Gown, Habit and Hood as Academic Dress," Transactions of the Burgon Society: Vol. 5. https://doi.org/10.4148/2475-7799.1038 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transactions of the Burgon Society by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transactions of the Burgon Society, 5 (2005), pages 42–58 Layer upon Layer: The Evolution of Cassock, Gown, Habit and Hood as Academic Dress by Alex Kerr Writers on the history of academic dress sometimes mistake which medieval garments were the antecedents of those worn in modern times. This happens especially when they misinterpret the evidence from memorial brasses and other pictorial sources. The situation is complicated by the fact that several Latin terms are used for a single article of dress in early university and college regulations and one term may refer to quite different articles at different periods. Now, as then, it is common to use words for clothing in both a narrow and a broad sense: for example, in modern English we use ‘jacket’ and ‘coat’ with various meanings, some of them overlapping or interchangeable. Similarly, in writing about medieval dress ‘gown’ or ‘robe’ may be a very specific item distinct from ‘cassock’ or ‘habit’ at one point, but any long, loose garment at another. -

Bio-Based Epichlorohydrin (ECH)

ANNUAL DISCLOSURE OF INFORMATION / ANNUAL REPORT 2020 OF INFORMATION ANNUAL DISCLOSURE ANNUAL DISCLOSURE OF INFORMATION / ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Vinythai Public Company Limited, PVC Resins, Chlor-Alkali and Epichlorohydrin Producer RESPONSIBILITY TOWARDS RESPONSIBILITY TOWARDS Annual Disclosureนf Information / Annual Report 2019 Annual Report 2018 Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 2016 Annual Report 2020 Annual Report 2015 Annual Report 2014 Annual Report 2013 Annual Report 2012 Annual Report 2011 Annual Report 2010 Annual Report 2009 Annual Report 2008 Annual Report 2007 Annual Report 2006 Annual Report 2005 Annual Report 2004 Annual Report 2003 Annual Report 2002 Annual Report 2001 Annual Report 2000 Annual Report 1999 Annual Report 1998 Annual Report 1997 Annual Report 1996 Vinythai Public Company Limited BKK Office: No. 944 Mitrtown Office Tower, 14th Floor, Rama 4 Road, Wangmai Sub-District, Pathumwan District, Bangkok 10330 Tel: (66) 0-2030-6800 Fax: (66) 0-2030-6801-2 Head Office (Plant): No. 2, I-3 Road, Map Ta Phut Industrial Estate, Map Ta Phut Sub-District, Mueang Rayong District, Rayong Province 21150 Tel: (66) 0-3892-5000 Fax: (66) 0-3868-3048 Website: www.vinythai.co.th, www.vinythaicoral.org RESPONSIBILITY TOWARDS ANNUAL DISCLOSURE OF INFORMATION / ANNUAL REPORT 2020 VINYTHAI PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED CONTENTS FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 4 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN 6 BUSINESS AND PERFORMANCE 8 Business Structure and Operation 9 Risk Management and Mitigation 30 Sustainability Management 36 Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) for -

M-033-009 1992-046.E

NOTICEOF INTENTTO COMMENCE MININGOPERATIONS KENNECOTTEXPLORATIONS (AUSTRALIO LTD. BARNEYSCANYON PROJECT SUBMITTEDTO UTAHDIVISION OF OIL GAS AND MINING KENNECOTTEXPLORATIONS (AUSTRALIA) LTD. 1515 MineralSquare Saft Lake City,Utah 84112 KENNECOTT'S e EXHIBIT o Docket N ,r-*t Cause No. M-035-009" TABLE OF CONIENTS PAGE# Form MR-MO 1.0 Inboduction 1 1.1 Locatios I L2 Land Ownership 2 Lz.t Srrrf;& Omershio 2 L22 SubsurfaceOum'ership 4 13 l-and Use 7 L.4 Existing Facilities 7 15 Mineral Exploration 7 1.6 Utilities and Accass 8 Slte Description. 9 2.1 Geologr 9 2.L.L QeologrcS-rlti9g . 9 2.t2 Geologyueorogy ofoI Mii-eralMtneral Deposits 11 2.t3 lupsryfgceSubsurface GeologGeoloqv of Process FacilitiesFar Site L2 2.1.4 Scisnicity. 2l 22 SurfaceWater Hydrologl ?2 23 Groundwater HydroloeY 25 23.1 Regioial Aqlifer Characteristics E 232 Local Recharse Characteristics 26 233 lncal Aquifer- Characteristics 29 23.4 Bascline Groundwater euality 33 2.4 Soils v 2.4.L fiOnicat'Apnroach v 2.42 loil Qpgs ..' 35 2.43 Topsoil Quality 39 4L 43 4 6 {I 48 2.6 Wildlife 49 3.0 Operation Plan 51 3.1 Descriptionof Mineral Deposits 51 O REVISED9.29.89 TABLE OF CONIENTS CONTINTJED o PAGE# MiniDg 51 32.1 MiniBg Opcrations 52 322 Mine Pit Configurations 53 323 Pit Slope SrabilityAnalltis 56 33 CtushingScreeningConveying and Stockpili"g 56 3.4 I*aching 62 3.4.1 l-each Pads 63 3,42 Solution Conrcyances. 70 3.43 Solution Posds 7t 35 Lcach Solution Processine . 75 35.1 Carbon AdsorpEon 75 ?5_.?Carbou $trippi"g . -

Costume Plot

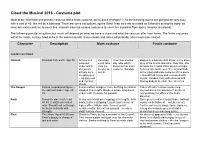

Cloud the Musical 2016 - Costume plot Most of the cast have one primary costume and a finale costume, so no quick changes! As the dressing rooms are going to be very cosy with a cast of 40, this will be a blessing. There are some exceptions, eg the Sand Tribe men are recruited as Enforcers during the story, so have one extra costume to cover this. Hannah also has various costumes to cover her transition from space traveller to colonist. The following provide an outline, but much will depend on what we have in store and what the cast can offer from home. The finale costumes will all be made, as they need to be in the same material. Some cloaks and robes will probably also need to be created. Character Description Main costume Finale costume Leaders on Cloud Hannah Scientist from Earth. Age 35. Arrives in a Receives Then has another Begins in a delicate shift dress, in the dove jump suit a soft robe day robe which grey of the scene. Barefoot. Over this, she under which from the becomes her main accepts the Crystal Robe as she accepts she wears Keeper to costume. Sandals. her new role as Keeper. The Crystal Robe military style rest in. is the most elaborate costume of the piece sleeping gear – should look heavy and encrusted with – eg grey vest crystal. Hooded, long wide sleeves and and ‘cycling’ flowing body in the skirt. See sketches. shorts The Keeper Poised, inspirational figure – A well-crafted ‘designer’ robe, befitting her station. Takes off robe to show simple long- the spiritual leader. -

17-6R Sale Prices Good Through December 31, 2017

Sale 17-6R CrowCalls Sale Prices Good Through December 31, 2017 1.800.786.6210 www.crazycrow.com 106 Silver Bark 716 Ranier Park 120 Jerome 717 Glacier Park 582 Suwanee Stripe 775 Santa Fe Saxony GREAT CHRISTMAS GIFTS Save 10% on Pendleton Closeouts!! Limited supply - Call for availability, other styles and colors available. Pendleton Towels 3710-233-*** 100% Cotton 40" x 70" Reg. $49.50 $44.55 Ea 106 120 582 716 717 775 Pendleton Robes 3710-***-*** 82% Virgin Wool 64" x 80" Reg. $249.00 $224.10 Ea 400-292 485-109 493-144 493-869 494-609 494-641 3710-***-*** Pendleton Serape Pendleton Chief Jo 82% Virgin Wool 64" x 80" Robe 411-*** 64" x 80" Reg. $249.00 $224.10 Ea Shawl 412-*** Reg. $249.00 $224.10 Ea Robe 3710-470-*** Reg. $189.00 $170.10 Ea Queen 413-*** 86" x 90" Reg. $369.00 $332.10 Ea Shawl 3710-477-*** Reg. $199.00 $179.10 Ea King 403-*** 108" x 86" Reg. $419.00 $377.10 Ea 116 118 119 100 103 105 Robe & Shawl Robe Only Shawl Only Queen Only Robe Only Robe & Shawl 141 148 156 106 183 184 Robe & Shawl Robe & Shawl Shawl Only Shawl Only Robe Only King & Queen Beaded Canvas Bags - 12”x 9.5” Canvas bag with beaded flap - Adjustable canvas strap - Two outer pockets and one zippered inside pocket - Made with real Czech Beads!! - Available in three beaded background colors 8545-150-001 Black 8545-150-081 Red 8545-150-240 Lt. Blue Reg. $29.50 $23.60 Ea $21.20 Ea(3+) 001 081 156 240 JacquardWeekender weave acrylic, Duffles Native American patterns available in 4 colors. -

West African Textiles

WEST AFRICAN TEXTILES BARROW HALL GALLERY March 4—April 3 9 a.m.—5 p.m. WEST AFRICAN TEXTILES Exhibit curated by José Blanco and Jennifer Regan with assistance from Dr. Patricia Hunt-Hurst, Raúl Vázquez -López, and students from TXMI 4580: World Textiles (Jessica Baker, Allie Bashuk, Lauren Fylstra, Sara Idacavage, Rachel Jack, Ashley Scruggs, Kim Stober, Danielle Walsh). Unknown maker Light teal and brown two piece female outfit, Burkina Faso Cotton, synthetic embroidery On loan from Dr. Karim Traore This female outfit represents the colorful and flamboyant prints of modern African fashion which contrast the hand woven designs of traditional African dress. It is interesting to note that the modern print of the ensemble is not a traditional African design and resembles the art deco style of the early twentieth century. The pattern is created by a wax-printing process that has been copied by the Europeans. Interestingly, English wax-printed fabrics have become prestigious items in Nigeria costing more than the local outputs of the region. The fabric is inscribed with the words “Guaranteed English Wax” therefore verifying the quality of the print. The second interesting feature of this ensemble is the colorfully embroidered collar around the neckline of the caftan that appears to be industrially made. The decorative elements of the ensemble indicate that it is probably intended for special occasions. Unknown maker Teal Kampala fabric with white and orange print, Nigeria Cotton brocade On loan from Dr. Akinloye Ojo This piece is similar to Kampala textiles created in Uganda. The material is likely a damask weave created with a synthetic fiber. -

Turn Teav: a Study of a Cambodian Literary Classic

Turn Teav: A Study of a Cambodian Literary Classic George V. Chigas II Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Of the University of London (School of Oriental and African Studies) 2001 ProQuest Number: 10731710 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731710 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 Abstract One of the cornerstones of the Cambodian literary canon is the verse novel Turn Teav. There are numerous versions o f the story that cover all the major modes of creative expression in Cambodian culture. In addition to the literary and theatrical versions, the story also appears in different historical texts, as it is generally believed that the characters described in the story are based on actual people and events in Cambodian history. Despite Turn Teav's tremendous importance and popularity however, there are no studies that examine the extensive literary criticism on the text or the influence of the story in contemporary Cambodian culture and society. This work is an attempt to present an overview o f the literary criticism on Turn Teav and provide the reader with an insight into the viewpoints of contemporary Cambodian writers and intellectuals on the major themes in the story.