Tabish Khair, the Gothic, Postcolonialism and Otherness: Ghosts from Elsewhere (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unseen Horrors: the Unmade Films of Hammer

Unseen Horrors: The Unmade Films of Hammer Thesis submitted by Kieran Foster In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy De Montfort University, March 2019 Abstract This doctoral thesis is an industrial study of Hammer Film Productions, focusing specifically on the period of 1955-2000, and foregrounding the company’s unmade projects as primary case studies throughout. It represents a significant academic intervention by being the first sustained industry study to primarily utilise unmade projects. The study uses these projects to examine the evolving production strategies of Hammer throughout this period, and to demonstrate the methodological benefits of utilising unmade case studies in production histories. Chapter 1 introduces the study, and sets out the scope, context and structure of the work. Chapter 2 reviews the relevant literature, considering unmade films relation to studies in adaptation, screenwriting, directing and producing, as well as existing works on Hammer Films. Chapter 3 begins the chronological study of Hammer, with the company attempting to capitalise on recent successes in the mid-1950s with three ambitious projects that ultimately failed to make it into production – Milton Subotsky’s Frankenstein, the would-be television series Tales of Frankenstein and Richard Matheson’s The Night Creatures. Chapter 4 examines Hammer’s attempt to revitalise one of its most reliable franchises – Dracula, in response to declining American interest in the company. Notably, with a project entitled Kali Devil Bride of Dracula. Chapter 5 examines the unmade project Nessie, and how it demonstrates Hammer’s shift in production strategy in the late 1970s, as it moved away from a reliance on American finance and towards a more internationalised, piece-meal approach to funding. -

Citation: Freeman, Sophie (2018) Adaptation to Survive: British Horror Cinema of the 1960S and 1970S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northumbria Research Link Citation: Freeman, Sophie (2018) Adaptation to Survive: British Horror Cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/39778/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html ADAPTATION TO SURVIVE: BRITISH HORROR CINEMA OF THE 1960S AND 1970S SOPHIE FREEMAN PhD March 2018 ADAPTATION TO SURVIVE: BRITISH HORROR CINEMA OF THE 1960S AND 1970S SOPHIE FREEMAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design & Social Sciences March 2018 Abstract The thesis focuses on British horror cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. -

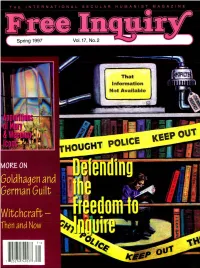

Soldhagen and German Guilt > "6Rx--/- SPRING 1997, VOL

THE INTERNATIONAL SECULAR HUMANIST MAGAZINE That Information Not Available OUI pOUCE KEEP GHT i MORE ON Soldhagen and German Guilt > SPRING 1997, VOL. 17, NO. 2 ISSN 0272-0701 Five Xr "6rX--/- Editor: Paul Kurtz Executive Editor: Timothy J. Madigan Contents Managing Editor: Andrea Szalanski Senior Editors: Vern Bullough, Thomas W. Flynn, James Haught, R. Joseph Hoffmann, Gerald Larue Contributing Editors: 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Robert S. Alley, Joe E. Barnhart, David Berman, H. James Birx, Jo Ann Boydston, Paul Edwards, 4 SEEING THINGS Albert Ellis, Roy P. Fairfield, Charles W. Faulkner, Antony Flew, Levi Fragell, Martin Gardner, Adolf 4 Tampa Bay's `Virgin Mary Apparition' Gary P Posner Grünbaum, Marvin Kohl, Jean Kotkin, Thelma Lavine, Tibor Machan, Ronald A. Lindsay, Michael 5 Those Tearful Icons Joe Nickell Martin, Delos B. McKown, Lee Nisbet, John Novak, Skipp Porteous, Howard Radest, Robert Rimmer, Michael Rockier, Svetozar Stojanoviu, Thomas Szasz, 8 The Honest Agnostic: V. M. Tarkunde, Richard Taylor, Rob Tielman Battling Demons of the Mind James A. Haught Associate Editors: Molleen Matsumura, Lois Porter Editorial Associates: 10 NOTES FROM THE EDITOR Doris Doyle, Thomas P. Franczyk, Roger Greeley, James Martin-Diaz, Steven L. Mitchell, Warren 10 Surviving Bypass and Enjoying the Exuberant Life: Allen Smith A Personal Account Paul Kurtz Cartoonist: Don Addis Council for Secular Humanism: Chairman: Paul Kurtz 14 THE FREEDOM TO INQUIRE Board of Directors: Vern Bullough, David Henehan, Joseph Levee, Kenneth Marsalek, Jean Millholland, 14 Introduction George D. Smith Lee Nisbet, Robert Worsfold 16 Atheism and Inquiry David Berman Chief Operating Officer: Timothy J. Madigan Executive Director: Matt Cherry 21 Inquiry: A Core Concept of John Dewey's Philosophy .. -

British Films 1971-1981

Preface This is a reproduction of the original 1983 publication, issued now in the interests of historical research. We have resisted the temptations of hindsight to change, or comment on, the text other than to correct spelling errors. The document therefore represents the period in which it was created, as well as the hard work of former colleagues of the BFI. Researchers will notice that the continuing debate about the definitions as to what constitutes a “British” production was topical, even then, and that criteria being considered in 1983 are still valid. Also note that the Dept of Trade registration scheme ceased in May 1985 and that the Eady Levy was abolished in the same year. Finally, please note that we have included reminders in one or two places to indicate where information could be misleading if taken for current. David Sharp Deputy Head (User Services) BFI National Library August 2005 ISBN: 0 85170 149 3 © BFI Information Services 2005 British Films 1971 – 1981: - back cover text to original 1983 publication. What makes a film British? Is it the source of its finance or the nationality of the production company and/or a certain percentage of its cast and crew? Is it possible to define a British content? These were the questions which had to be addressed in compiling British Films 1971 – 1981. The publication includes commercial features either made and/or released in Britain between 1971 and 1981 and lists them alphabetically and by year of registration (where appropriate). Information given for each film includes production company, studio and/or major location, running time, director and references to trade paper production charts and Monthly Film Bulletin reviews as source of more detailed information. -

The Drink Tank262 - Ireland Travelling to Ireland and Not Wanting to Leave

The Drink Tank262 - Ireland Travelling to Ireland and not wanting to leave. By James Bacon Could not be easier. The time is good for the cheap fare offers, with Ryan Air bringing prices down with their competitors. To Dublin, it’s a choice, Ryan Air, BMI and then Aerlingus, with Aer Lingus frequently doing the best deal. It pays to shop around. As I write this piece, a flight to Dublin on the Friday before WexWorlds is just £39. While flights to Octocon, from Manchester or London Gatwick were £39 all included, although you have 10kilos of carry on, and that’s it. And use the loo before you go. To be honest for all the mirth and mockery, O’Leary does what he says, it’s cheap and if you plan a bit, you can find good deals, from Dublin Airport is a Bus and Train, and if you plan it cleverly, you can be on the quays, enjoying a pint in the afternoon, the glow of a heater keeping off the chill, after leaving home in the morning. I recently travelled home from London using sail and rail. The 9.10 Virgin trains service from London Euston goes directly to Holyhead. It’s a very pleasant journey. They stick on a ten car unit as far as Chester, so there is ample space, and there is nothing nicer than a plug, a table and the feeling that a coffee or loo is not a mission, but just there. It’s quite an old fashioned way to travel, yet there is something sedate about it. -

"Vers Mes Dix Ans, J'allais Souvent Voir Des Films Avec Un Groupe D'amis. Si Nous Voyions Le Logo De Hammer Films Nous Savi

"Vers mes dix ans, j'allais souvent voir des films avec un groupe d'amis. Si nous voyions le logo de Hammer Films nous savions que cela allait être un film très spécial... une expérience surprenante, bien souvent- et choquante ". (M. Scorsese, dans " The Studio That Dripped Blood ") En mai 1957, un film d'horreur britannique intitulé "The Curse of Frankenstein " (" La Malédiction de Frankenstein ") sortait dans les salles obscures londoniennes. Ce film fit de Christopher Lee et de Peter Cushing des stars internationales et de la Hammer Films, une maison de production de renomée mondiale. A cette époque, la Hammer sortait 5 films par ans, puisant largement (selon certains, peut-être trop...) dans la "matière gothique" et des grands mythes littéraires auxquels elle a donné naissance. Pourtant, l'histoire de la Hammer ne commence pas là... L'initiateur de cette compagnie légendaire est Enrique Carreras qui naquit en Espagne en 1880. Il émigra en Angleterre où il ouvrit un théatre qui sera considéré comme un des premiers multi-plex. Il comptait en effet deux salles ("Blue Halls"), permettant donc de projeter des films différents, et qui offraient 2000 places assises. A la fin des années 1920, Carrera créa une compagnie permettant la distribution de films anglais : l'Exclusive Films. A cette même époque commença à poindre la mode du vaudeville, avec en tête de file la compagnie "Hammer and Smith", dirigée par William Hinds. En 1932, Carreras s'associa avec Hinds et assurèrent les droits de distribution de nombre de films (en particulier ceux de la Brittish Lion). Finalement, ils décidèrent de créer une compagnie détachée et destinée à distribuer les films de l'Exclusive. -

Now in It's 30 Year 25Th

Now in it’s 30th Year 25th - 27th October 2019 Welcome to the first progress report for our 30th festival. This annual event has become part of our lives and we would like to thank you all for the support you have shown. We have already lined up some great guests and we are working to add a few more surprises. Please let us know what you want to see and how you think we should celebrate three decades? Guests We are pleased to announce that the following guests have confirmed that they can attend (subject to work commitments). Dana Deirdre Pauline Peart Lawrence Costello Gordon Clark Gillespie 1 A message from the Festival’s Chairman As we reach the 30th anniversary of the annual event which has brought us both friendships and a weekend when we can usually park our 1990 brains in automatic control, I have been recently reminding myself of some of the highlights (and lowlights) of the Festival which has become a 1991 real part of my life. When we started I was a relatively young man of 43 and look at me now. I believe that some of the creatures/monsters that we have seen in 1992 the films we have watched over that period have probably kept their looks better than me but what the hell, I have enjoyed almost every minute of it. 1993 What does bother me is how Tony Edwards, who started the event older than me, now seems to have found the fountain of youth and 1994 looks younger than I do! Anyway, to the point, I hope that you all enjoy the coming event, and I am grateful for the 1995 positive response received from those attending Festival number 29 last year. -

University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue 02 | Spring 2006

University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue 02 | Spring 2006 Title Notes on the Terror Film Author Keith Hennessey Brown Publication FORUM: University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue Number 02 Issue Date Spring 2006 Publication Date 05/06/2006 Editors Joe Hughes & Beth Schroeder FORUM claims non-exclusive rights to reproduce this article electronically (in full or in part) and to publish this work in any such media current or later developed. The author retains all rights, including the right to be identified as the author wherever and whenever this article is published, and the right to use all or part of the article and abstracts, with or without revision or modification in compilations or other publications. Any latter publication shall recognise FORUM as the original publisher. FORUM ‘Fear and Terror’ 1 1 Notes on the Terror Film Keith Hennessey Brown (University of Edinburgh) Horror is, without question, among film's most enduring genres; audiences in search of thrills have been able to find a chiller to attend since the turn of the century. Even the studio of film pioneer Thomas Edison produced a 16-minute version of the Frankenstein story in 1910. The remarkable longevity of the genre does not, however, guarantee that a near century's worth of fans have all been lining up for the same motion picture show. (Lake Crane: 23) As Jonathan Lake Crane's perceptive comments indicate, the horror film is a remarkably resilient and adaptable film genre, one that has been able to meet the needs of successive generations of audiences in a way that others, like musicals and westerns, apparently have not, in the light of their declining production in recent decades. -

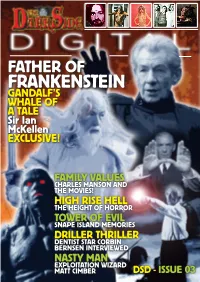

FRANKENSTEIN GANDALF’S WHALE of a TALE Sir Ian Mckellen EXCLUSIVE!

FATHER OF FRANKENSTEIN GANDALF’S WHALE OF A TALE Sir Ian McKellen EXCLUSIVE! FAMILY VALUES CHARLES MANSON AND THE MOVIES! HIGH RISE HELL THE HEIGHT OF HORROR TOWER OF EVIL SNAPE ISLAND MEMORIES DRILLER THRILLER DENTIST STAR CORBIN BERNSEN INTERVIEWED NASTY MAN EXploitation WIZard Matt Cimber DSD - ISSUE 03 “ONE OF THE UNDISPUTED HIGH POINTS OF HORROR TELEVISION... NIGEL KNEALE’S MASTERFUL MIX OF THE SCIENTIFIC AND THE SUPERNATURAL CAN STILL HAUNT YOU LIKE NO OTHER” PHELIM O’NEILL – THE GUARDIAN Nigel (Quatermass) Kneale’s legendary small screen frightener The Stone Tape was originally commissioned as a feature length ghost story for Christmas in 1972. The setting for this creepy classic is a traditionally spooky old house which is bought by an electronics company to house their new recording media research division. The building has been completely renovated apart from one room that the superstitious workmen have refused to enter. Of course computer programmers, Peter (Michael Bryant) and Jill (Jane Asher) are made of sterner stuff and investigate the room, finding nothing more scary than a few tins of pre-war spam and a letter to Santa from a young girl probably now long dead. Things get a bit more spooky though when the scientists knock down an old wood panel to discover a stone staircase. It is on this that the psychically susceptible Jill sees the ghost of a terrified 19th-century servant girl. Peter believes in what she has seen but treats it as a scientific problem. He thinks that the stone walls have acted like a kind of recording tape to keep replaying this traumatic event and determines to use this ghostly event to further his team’s research. -

Freeman.Sophie Phd.Pdf

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Freeman, Sophie (2018) Adaptation to Survive: British Horror Cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/39778/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html ADAPTATION TO SURVIVE: BRITISH HORROR CINEMA OF THE 1960S AND 1970S SOPHIE FREEMAN PhD March 2018 ADAPTATION TO SURVIVE: BRITISH HORROR CINEMA OF THE 1960S AND 1970S SOPHIE FREEMAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design & Social Sciences March 2018 Abstract The thesis focuses on British horror cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. This was a lively period in British horror history which produced over two hundred films, but it has often been taken for granted in critical work on both British horror and British national cinema, with most of the films concerned left underexplored or ignored entirely. -

October 2009 Newspaper

A monthly guide to your community library, its programs and services Issue No. 247, October 2009 Library schedule The library will be open from 1 to 5 on 5th Annual Celebration of Long Island Talent Monday, October 12 in observance of Columbus Day. On Sunday, October 25 at 3 p.m., you’re invited to join John Platt, host of WFUV’s Sunday Morn- ing Breakfast, for an afternoon of Science 103 homegrown, hand picked musical Art and Mathematics – How do they performances. influence each other? Art and math- Blue Detour began collaborating ematics have become more interre- 1996 and plays both traditional and lated than ever before. Join Philip M. more modern bluegrass done with Sherman on October 1 at 4 p.m. for a Northeastern flavor. George Can- an in-depth exploration of this topic nova, Julie Cannova, John Chainey We’ll emphasize how mathematics and Dennis Corbett are native Long generates, inspires and abets art. See Islanders who really enjoy playing calendar for details. together. Steve Robinson, winner of the 2007 Long Island Blues Society’s Blues Challenge, is a native Long FOL University on Islander. He has been a carpen- ter, high school English teacher, October 4 Join the Friends of the Library for a commercial shell fisherman, truck unique program of stimulating intellec- tual fare. Two university professors . continued on page 7 two fascinating topics. Story inside. Attention Book Clubs! Our Book Club in a Bag selection is expanding! In addition to the titles carried by the PWPL, you may now reserve titles from the 6 other libraries in our system that carry Book Club in a Bag. -

Nosferatu. Revista De Cine (Donostia Kultura)

Nosferatu. Revista de cine (Donostia Kultura) Título: Hammer Films: una herencia de miedo Autor/es: Molina Foix, Juan Antonio Citar como: Molina Foix, JA. (1991). Hammer Films: una herencia de miedo. Nosferatu. Revista de cine. (6):4-21. Documento descargado de: http://hdl.handle.net/10251/43305 Copyright: Reserva de todos los derechos (NO CC) La digitalización de este artículo se enmarca dentro del proyecto "Estudio y análisis para el desarrollo de una red de conocimiento sobre estudios fílmicos a través de plataformas web 2.0", financiado por el Plan Nacional de I+D+i del Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad del Gobierno de España (código HAR2010-18648), con el apoyo de Biblioteca y Documentación Científica y del Área de Sistemas de Información y Comunicaciones (ASIC) del Vicerrectorado de las Tecnologías de la Información y de las Comunicaciones de la Universitat Politècnica de València. Entidades colaboradoras: The Curse of the Werewolf (Terence Fisher, 1960). Mi chae l Carreras, "e l" productor de la Hammer. Pese al innegable origen (literario) británico de los grandes mitos clásicos del cine de terror (Frankenstein, Drácula, Jekyll & Hyde, la Momia, el Hombre Invisible, el Dr. Moreau, etc.), así como de la mayoría de sus más conocidos intérpretes o creadores (Boris Karloff, James Whale, Charles Laughton, Claude Rains, Basil Rathbone, Lionel Atwill, George Zueco, Colín Clive, Ernest Thesiger, Leslie Banks, Elsa Lanchester, etc.), la cinematografía del Reino Unido apenas se había interesado por dicho género hasta mediados los años cincuenta. Ni siquiera el regreso momentáneo de Karloff a su patria para rodar en 1933 El resucitado (The Ghoul), primer film "de horror" inglés a la manera de Hollywood, y en 1936 El hombre que trocó su mente (The Man Who Changed his Mind), logró cambiar sustancialmente el panorama.