The Case Study of Gordon Hessler and Christopher Wicking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Matieland to Mother City: Landscape, Identity and Place in Feature Films Set in the Cape Province, 1947-1989.”

“FROM MATIELAND TO MOTHER CITY: LANDSCAPE, IDENTITY AND PLACE IN FEATURE FILMS SET IN THE CAPE PROVINCE, 1947-1989.” EUSTACIA JEANNE RILEY Thesis Presented for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Historical Studies UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN December 2012 Supervisor: Vivian Bickford-Smith Table of Contents Abstract v Acknowledgements vii Introduction 1 1 The Cape apartheid landscape on film 4 2 Significance and literature review 9 3 Methodology 16 3.1 Films as primary sources 16 3.2 A critical visual methodology 19 4 Thesis structure and chapter outline 21 Chapter 1: Foundational Cape landscapes in Afrikaans feature films, 1947- 1958 25 Introduction 25 Context 27 1 Afrikaner nationalism and identity in the rural Cape: Simon Beyers, Hans die Skipper and Matieland 32 1.1 Simon Beyers (1947) 34 1.2 Hans die Skipper (1953) 41 1.3 Matieland (1955) 52 2 The Mother City as a scenic metropolitan destination and military hub: Fratse in die Vloot 60 Conclusion 66 Chapter 2: Mother city/metropolis: representations of the Cape Town land- and cityscape in feature films of the 1960s 69 Introduction 69 Context 70 1 Picturesque Cape Town 76 1.1 The exotic picturesque 87 1.2 The anti-picturesque 90 1.3 A picturesque for Afrikaners 94 2 Metropolis of Tomorrow 97 2.1 Cold War modernity 102 i Conclusion 108 Chapter 3: "Just a bowl of cherries”: representations of landscape and Afrikaner identity in feature films made in the Cape Province in the 1970s 111 Introduction 111 Context 112 1 A brief survey of 1970s film landscapes 118 2 Picturesque -

Guests We Are Pleased to Announce That the Following Guests Have Confirmed That They Can Attend

Welcome to this progress report for the Festival. Every year we start with a big task… be better than before. With 28 years of festivals under our belts it’s a big ask, but from the feedback we receive expectations are usually exceeded. The biggest source of disappointment from attendees is that they didn’t hear about the festival earlier and missed out on some fantastic weekends. The upcoming 29th Festival of Fantastic Films will be held over the weekend of October 26– 28 in the Manchester Conference Centre (The Pendulum Hotel) and looks set to be another cracker. So do everyone a favour and spread the word. Guests We are pleased to announce that the following guests have confirmed that they can attend Michael Craig Simon Andreu Aldo Lado Dez Skinn Ray Brady 1 A message from the Festival’s Chairman And so we approach the 29th Festival - a position that none of us who began it all could ever have envisioned. We thought that if it went on for about five years, we would be happy. My biggest regret is that I am the only one of that original formation group who is still actively involved in the organisation. I'm not sure if that's because I am a real survivor or if I just don't like quitting. Each year as we look at putting on another Festival, I think of those people who were there at the outset - Harry Nadler, Dave Trengove, and Tony Edwards, without whom the event wouldn’t be what it is. -

Australian Radio Series

Radio Series Collection Guide1 Australian Radio Series 1930s to 1970s A guide to ScreenSound Australia’s holdings 1 Radio Series Collection Guide2 Copyright 1998 National Film and Sound Archive All rights reserved. No reproduction without permission. First published 1998 ScreenSound Australia McCoy Circuit, Acton ACT 2600 GPO Box 2002, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone (02) 6248 2000 Fax (02) 6248 2165 E-mail: [email protected] World Wide Web: http://www.screensound.gov.au ISSN: Cover design by MA@D Communication 2 Radio Series Collection Guide3 Contents Foreword i Introduction iii How to use this guide iv How to access collection material vi Radio Series listing 1 - Reference sources Index 3 Radio Series Collection Guide4 Foreword By Richard Lane* Radio serials in Australia date back to the 1930s, when Fred and Maggie Everybody, Coronets of England, The March of Time and the inimitable Yes, What? featured on wireless sets across the nation. Many of Australia’s greatest radio serials were produced during the 1940s. Among those listed in this guide are the Sunday night one-hour plays - The Lux Radio Theatre and The Macquarie Radio Theatre (becoming the Caltex Theatre after 1947); the many Jack Davey Shows, and The Bob Dyer Show; the Colgate Palmolive variety extravaganzas, headed by Calling the Stars, The Youth Show and McCackie Mansion, which starred the outrageously funny Mo (Roy Rene). Fine drama programs produced in Sydney in the 1940s included The Library of the Air and Max Afford's serial Hagen's Circus. Among the comedy programs listed from this decade are the George Wallace Shows, and Mrs 'Obbs with its hilariously garbled language. -

Rosemary Ellen Guiley

vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page i The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page ii The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS Rosemary Ellen Guiley FOREWORD BY Jeanne Keyes Youngson, President and Founder of the Vampire Empire The Encyclopedia of Vampires, Werewolves, and Other Monsters Copyright © 2005 by Visionary Living, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guiley, Rosemary. The encyclopedia of vampires, werewolves, and other monsters / Rosemary Ellen Guiley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4684-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4381-3001-9 (e-book) 1. Vampires—Encyclopedias. 2. Werewolves—Encyclopedias. 3. Monsters—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BF1556.G86 2004 133.4’23—dc22 2003026592 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Register of Entertainers, Actors and Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa

Register of Entertainers, Actors And Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1988_10 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Register of Entertainers, Actors And Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 11/88 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid Publisher United Nations, New York Date 1988-08-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1981 - 1988 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description INTRODUCTION. REGISTER OF ENTERTAINERS, ACTORS AND OTHERS WHO HAVE PERFORMED IN APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA SINCE JANUARY 1981. -

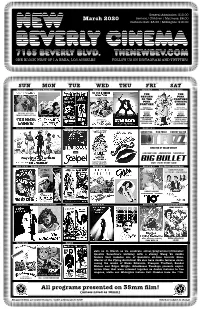

Newbev202003 FRONT

General Admission: $12.00 March 2020 Seniors / Children / Matinees: $8.00 NEW Cartoon Club: $8.00 / Midnights: $10.00 BEVERLY cinema 7165 BEVERLY BLVD. THENEWBEV.COM ONE BLOCK WEST OF LA BREA, LOS ANGELES FOLLOW US ON INSTAGRAM AND TWITTER! SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT March 1 & 2 Directed by Randal Kleiser March 3 March 4 & 5 March 6 & 7 Blake Edwards / Peter Sellers THE THE RETURN PINK OF THE PANTHER PINK STRIKES PANTHER AGAIN DIRECTED BY DIRECTED BY BLAKE EDWARDS BLAKE EDWARDS STARRING STARRING BROOKE SHIELDS PETER PETER CHRISTOPHER ATKINS SELLERS SELLERS CHRISTOPHER HERBERT LOM JOHN HUSTON’S PLUMMER COLIN BLAKELY CATHERINE SCHELL LEONARD ROSSITER HERBERT LOM LESLEY-ANNE DOWN March 8 & 9 Directed by Blake Edwards March 10 March 11 & 12 March 13 & 14 SIMON PEGG NICK FROST TIMOTHY DALTON DIRECTED BY EDGAR WRIGHT PLUS! BIGLAU CHING-WAN BULLET JORDAN CHAN THERESA LEE UGO TOGNAZZI MICHEL SERRAULT DIRECTED BY BENNY CHAN March 15 & 16 Barbara Stanwyck Double Feature March 17 March 18 & 19 March 20 & 21 Blake Edwards / Dudley Moore DUDLEY MOORE AMY IRVING ANN REINKING DUDLEY MOORE JULIE ANDREWS BO DEREK March 22 & 23 Directed by François Truffaut March 24 March 25 & 26 March 27 & 28 Quentin’s Birthday Double Feature JIMMY WANG YU Written, Directed by, and Starring Written & Directed by JIMMY WANG YU LO WEI March 29 & 30 March 31 Join us in March as we celebrate owner/programmer/fi lmmaker Quentin Tarantino’s birthday with a Jimmy Wang Yu double IB Tech Print feature that includes one of Quentin’s all-time favorite fi lms, IB Tech Print Master of the Flying Guillotine! We also have double features show- casing the works of Blake Edwards, François Truff aut, Randal Kleiser and Edgar Wright. -

Unseen Horrors: the Unmade Films of Hammer

Unseen Horrors: The Unmade Films of Hammer Thesis submitted by Kieran Foster In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy De Montfort University, March 2019 Abstract This doctoral thesis is an industrial study of Hammer Film Productions, focusing specifically on the period of 1955-2000, and foregrounding the company’s unmade projects as primary case studies throughout. It represents a significant academic intervention by being the first sustained industry study to primarily utilise unmade projects. The study uses these projects to examine the evolving production strategies of Hammer throughout this period, and to demonstrate the methodological benefits of utilising unmade case studies in production histories. Chapter 1 introduces the study, and sets out the scope, context and structure of the work. Chapter 2 reviews the relevant literature, considering unmade films relation to studies in adaptation, screenwriting, directing and producing, as well as existing works on Hammer Films. Chapter 3 begins the chronological study of Hammer, with the company attempting to capitalise on recent successes in the mid-1950s with three ambitious projects that ultimately failed to make it into production – Milton Subotsky’s Frankenstein, the would-be television series Tales of Frankenstein and Richard Matheson’s The Night Creatures. Chapter 4 examines Hammer’s attempt to revitalise one of its most reliable franchises – Dracula, in response to declining American interest in the company. Notably, with a project entitled Kali Devil Bride of Dracula. Chapter 5 examines the unmade project Nessie, and how it demonstrates Hammer’s shift in production strategy in the late 1970s, as it moved away from a reliance on American finance and towards a more internationalised, piece-meal approach to funding. -

DVD Profiler

101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure Animation Family Comedy2003 74 minG Coll.# 1 C Barry Bostwick, Jason Alexander, The endearing tale of Disney's animated classic '101 Dalmatians' continues in the delightful, all-new movie, '101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London A Martin Short, Bobby Lockwood, Adventure'. It's a fun-filled adventure fresh with irresistible original music and loveable new characters, voiced by Jason Alexander, Martin Short and S Susan Blakeslee, Samuel West, Barry Bostwick. Maurice LaMarche, Jeff Bennett, T D.Jim Kammerud P. Carolyn Bates C. W. Garrett K. SchiffM. Geoff Foster 102 Dalmatians Family 2000 100 min G Coll.# 2 C Eric Idle, Glenn Close, Gerard Get ready for outrageous fun in Disney's '102 Dalmatians'. It's a brand-new, hilarious adventure, starring the audacious Oddball, the spotless A Depardieu, Ioan Gruffudd, Alice Dalmatian puppy on a search for her rightful spots, and Waddlesworth, the wisecracking, delusional macaw who thinks he's a Rottweiler. Barking S Evans, Tim McInnerny, Ben mad, this unlikely duo leads a posse of puppies on a mission to outfox the wildly wicked, ever-scheming Cruella De Vil. Filled with chases, close Crompton, Carol MacReady, Ian calls, hilarious antics and thrilling escapes all the way from London through the streets of Paris - and a Parisian bakery - this adventure-packed tale T D.Kevin Lima P. Edward S. Feldman C. Adrian BiddleW. Dodie SmithM. David Newman 16 Blocks: Widescreen Edition Action Suspense/Thriller Drama 2005 102 min PG-13 Coll.# 390 C Bruce Willis, Mos Def, David From 'Lethal Weapon' director Richard Donner comes "a hard-to-beat thriller" (Gene Shalit, 'Today'/NBC-TV). -

Citation: Freeman, Sophie (2018) Adaptation to Survive: British Horror Cinema of the 1960S and 1970S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northumbria Research Link Citation: Freeman, Sophie (2018) Adaptation to Survive: British Horror Cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/39778/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html ADAPTATION TO SURVIVE: BRITISH HORROR CINEMA OF THE 1960S AND 1970S SOPHIE FREEMAN PhD March 2018 ADAPTATION TO SURVIVE: BRITISH HORROR CINEMA OF THE 1960S AND 1970S SOPHIE FREEMAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design & Social Sciences March 2018 Abstract The thesis focuses on British horror cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. -

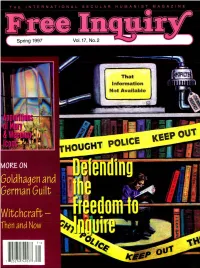

Soldhagen and German Guilt > "6Rx--/- SPRING 1997, VOL

THE INTERNATIONAL SECULAR HUMANIST MAGAZINE That Information Not Available OUI pOUCE KEEP GHT i MORE ON Soldhagen and German Guilt > SPRING 1997, VOL. 17, NO. 2 ISSN 0272-0701 Five Xr "6rX--/- Editor: Paul Kurtz Executive Editor: Timothy J. Madigan Contents Managing Editor: Andrea Szalanski Senior Editors: Vern Bullough, Thomas W. Flynn, James Haught, R. Joseph Hoffmann, Gerald Larue Contributing Editors: 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Robert S. Alley, Joe E. Barnhart, David Berman, H. James Birx, Jo Ann Boydston, Paul Edwards, 4 SEEING THINGS Albert Ellis, Roy P. Fairfield, Charles W. Faulkner, Antony Flew, Levi Fragell, Martin Gardner, Adolf 4 Tampa Bay's `Virgin Mary Apparition' Gary P Posner Grünbaum, Marvin Kohl, Jean Kotkin, Thelma Lavine, Tibor Machan, Ronald A. Lindsay, Michael 5 Those Tearful Icons Joe Nickell Martin, Delos B. McKown, Lee Nisbet, John Novak, Skipp Porteous, Howard Radest, Robert Rimmer, Michael Rockier, Svetozar Stojanoviu, Thomas Szasz, 8 The Honest Agnostic: V. M. Tarkunde, Richard Taylor, Rob Tielman Battling Demons of the Mind James A. Haught Associate Editors: Molleen Matsumura, Lois Porter Editorial Associates: 10 NOTES FROM THE EDITOR Doris Doyle, Thomas P. Franczyk, Roger Greeley, James Martin-Diaz, Steven L. Mitchell, Warren 10 Surviving Bypass and Enjoying the Exuberant Life: Allen Smith A Personal Account Paul Kurtz Cartoonist: Don Addis Council for Secular Humanism: Chairman: Paul Kurtz 14 THE FREEDOM TO INQUIRE Board of Directors: Vern Bullough, David Henehan, Joseph Levee, Kenneth Marsalek, Jean Millholland, 14 Introduction George D. Smith Lee Nisbet, Robert Worsfold 16 Atheism and Inquiry David Berman Chief Operating Officer: Timothy J. Madigan Executive Director: Matt Cherry 21 Inquiry: A Core Concept of John Dewey's Philosophy .. -

British Films 1971-1981

Preface This is a reproduction of the original 1983 publication, issued now in the interests of historical research. We have resisted the temptations of hindsight to change, or comment on, the text other than to correct spelling errors. The document therefore represents the period in which it was created, as well as the hard work of former colleagues of the BFI. Researchers will notice that the continuing debate about the definitions as to what constitutes a “British” production was topical, even then, and that criteria being considered in 1983 are still valid. Also note that the Dept of Trade registration scheme ceased in May 1985 and that the Eady Levy was abolished in the same year. Finally, please note that we have included reminders in one or two places to indicate where information could be misleading if taken for current. David Sharp Deputy Head (User Services) BFI National Library August 2005 ISBN: 0 85170 149 3 © BFI Information Services 2005 British Films 1971 – 1981: - back cover text to original 1983 publication. What makes a film British? Is it the source of its finance or the nationality of the production company and/or a certain percentage of its cast and crew? Is it possible to define a British content? These were the questions which had to be addressed in compiling British Films 1971 – 1981. The publication includes commercial features either made and/or released in Britain between 1971 and 1981 and lists them alphabetically and by year of registration (where appropriate). Information given for each film includes production company, studio and/or major location, running time, director and references to trade paper production charts and Monthly Film Bulletin reviews as source of more detailed information. -

The Bearing in Tbe Above-Entitled Matter Was Reconvened Pursuant

I COPYRIGHT ROYALTY TRIBUNAL lXL UI I 1 I I In the Matter og ~ CABLE COPYRIGHT ROYALTY CRT 85-4-84CD DISTRIBUTION PHASE II (This volume contains page 646 through 733) 10 llll 20th Street, Northwest Room 458 Washington, D. C. 12 Friday, October 31, 1986 13 The bearing in tbe above-entitled matter was reconvened pursuant. to adjournment, at 9:30 a.m. BEFORE EDWARD.W. RAY Chairman 20 MARI 0 F . AGUERO Commissioner 21 J. C. ARGETSINGER Commissioner 23 ROBERT CASSLER General Counsel 24 HEAL R. GROSS COURT REPORTERS AND TRANSCRIBERS 1323 RHODE ISLAND AVENUE, IW.W. {202) 234-4433 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005 {202) 232-6600 647 APPEARANCES: 2 On beha'lf of MPAA: DENNIS LANE, ESQ. Wilner R Scheiner Suite 300 1200 New Hampshire Avenue, Northwest Washington, D. C. 20036 6 On behalf of NAB: JOHN STEWART, ESQ. ALEXANDRA WILSON, ESQ. Crowell S Moring 1100 Connecticut Avenue, Northwest Washington, D. C. 20036 On behalf of Warner Communicate.ons: ROBERT GARRETT, ESQ. Arnold a Porter 1200 New Hampshire Avenue, Northwest Washington, D. C. 20036 13 On behalf of Multimedia Entertainment: ARNOLD P. LUTZKER, ESQ. 15 Dow, Lohnes a Albertson. 1255 23rd Street, Northwest. Washington, D. C. 20037 On bahalf of ASCAP: I, FRED KOENIGSBERG, ESQ. Senior Attorney, OGC One Lincoln Plaza New York, New York 10023 20 22 23 24 HEAL R. GROSS COURT REPORTERS AND TRANSCRI8ERS I323 RHODE ISLAND AVENUE, N.W. (202) 234-4433 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005 (202) 232-6600 648 CONTENTS WITNESS DIRECT 'CROSS VOIR 'DI'RE TR'QBUNAL 3 , ALLEN R. COOPER 649,664 By Ms.